Introduction

Eosinophilic lung diseases are characterized by the presence of pulmonary opacities and peripheral blood eosinophilia, tissue eosinophilia, or both. Eosinophils are leukocytes that are involved in immune defense and various inflammatory processes. They decrease hypersensitivity reactions by reducing the activity of histamine and leukotriene complexes released by mast cells, as well as by phagocytizing mast cell granules and immune complexes. Eosinophils also release cytotoxic proteins such as major basic protein and eosinophilic cationic protein, which are helpful in destroying parasites, but are also responsible for most of the tissue damage present in eosinophilic lung diseases.

Approach to Diagnosis

Eosinophilic lung diseases can be challenging to diagnose, and a combined clinical, radiologic, and pathologic approach is essential. The clinical history and physical examination are important for determining the extent and duration of signs and symptoms. A diagnosis of asthma, travel history, occupational and environmental exposures, and previous and current medications are also important to identify.

Laboratory studies that aid in the diagnosis of eosinophilic lung disease include a white blood cell count with differential to look for peripheral blood eosinophilia, serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) level, and serum Aspergillus precipitins, and stool studies for cysts, ova, and parasites. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is defined as an eosinophil count >0.4 × 10 9 /L. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is elevated in most eosinophilic lung diseases.

Diagnostic procedures that can help establish a diagnosis of eosinophilic lung disease include pulmonary function tests and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Pulmonary function tests in patients with eosinophilic lung disease can show different patterns of disease. A restrictive defect usually occurs with acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP), chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP), and tropical eosinophilic pneumonia. An obstructive defect usually occurs with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS). BAL is an extremely helpful test in diagnosing eosinophilic lung disease. Normal BAL fluid contains <1% eosinophils, whereas eosinophilic lung diseases are associated with BAL fluid with usually >10% eosinophils.

Sputum and tissue analysis can show Charcot-Leyden crystals, which are derived from a protein released by eosinophils. These crystals are present whenever there are large numbers of eosinophils present and thus are typically seen in eosinophilic lung diseases.

Both chest radiography and chest CT can show pulmonary opacities suggestive of eosinophilic lung disease. Transbronchial or surgical lung biopsy may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis in challenging cases.

A diagnosis of eosinophilic lung disease can be made if there is pulmonary opacity present on imaging studies and peripheral blood eosinophilia, biopsy confirmation of tissue eosinophilia, or increased eosinophils in BAL fluid. Additionally, Hodgkin lymphoma, sarcoidosis, infection, and hydatid disease must be excluded before a diagnosis of eosinophilic lung disease can be established.

Available Imaging Modalities to Evaluate Eosinophilic Lung Disease

Imaging procedures available to evaluate pulmonary eosinophilic disease include chest radiography and CT. Chest radiography is useful as a screening examination to detect pulmonary opacities, given its relatively low cost and low patient exposure to ionizing radiation. However, chest radiographic findings are nonspecific and may even be absent in patients with eosinophilic lung disease. In contrast, CT is more sensitive to the presence of lung opacities and sometimes shows a more specific pattern of disease, helping to narrow the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, CT can also be helpful in planning a transbronchial or surgical biopsy. However, compared to chest radiography, CT is more costly and results in higher levels of patient exposure to ionizing radiation.

Eosinophilic Lung Diseases

Eosinophilic lung diseases are divided into diseases with known causes and diseases with unknown causes.

- •

Eosinophilic lung diseases without a known cause:

- 1.

Simple eosinophilic pneumonia (SEP)

- 2.

CEP

- 3.

AEP

- 4.

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome

- 1.

- •

Eosinophilic diseases with a known cause:

- 1.

ABPA

- 2.

Bronchocentric granulomatous inflammation

- 3.

CSS

- 4.

Drug reactions

- 5.

Parasite infection

- 1.

Diseases Without a Known Cause

Simple Eosinophilic Pneumonia

SEP, also known as Löffler syndrome, is an idiopathic disease characterized by migrating pulmonary consolidation and peripheral blood eosinophilia. Symptoms are often mild and include cough, fever, and dyspnea.

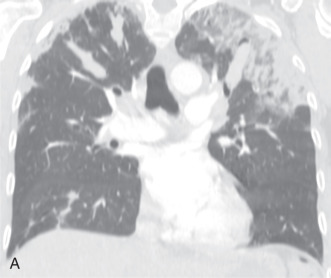

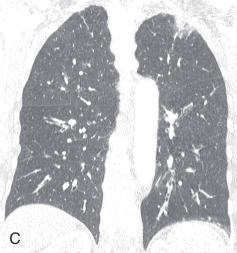

Chest radiographs show migratory foci of consolidation that usually clear spontaneously within 1 month. Foci of consolidation are typically upper lung predominant and peripheral in location. CT shows peripheral ground-glass opacity, consolidation, or both in the mid and upper lungs ( Fig. 22.1 ). Nodules with surrounding ground-glass opacity may also be present. Pleural effusion, cavitation, and lymphadenopathy are absent. Histopathologically, eosinophils are seen infiltrating the alveolar septa and interstitium. The main differential diagnostic considerations include vasculitis and organizing pneumonia. Response to corticosteroids is excellent if treatment is necessary, and the prognosis is excellent.

Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia

CEP is an idiopathic eosinophilic lung disease with insidious onset. Signs and symptoms are usually present for more than 6 months before the diagnosis is established and include cough, fever, night sweats, dyspnea, and weight loss. Patients usually are middle-age women, and approximately 50% have a history of asthma or atopy.

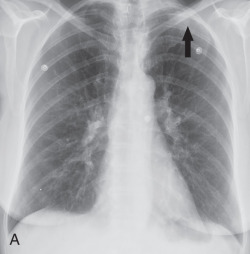

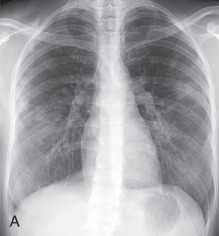

Patients usually have leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a variable IgE level. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is present in approximately 90% of patients, but may be absent later in the disease process. Pulmonary function tests usually show a restrictive defect, and BAL usually shows >25% eosinophils. Characteristic chest radiographic and CT findings include peripheral areas of upper lung predominant ground-glass opacity and consolidation, which sometimes contain air bronchograms ( Fig. 22.2 ). However, other patterns of disease, including mixed peripheral and perihilar consolidation and unilateral disease, are also possible. Nodules, reticulation, and pleural effusion are less common findings and usually occur later in the disease course. On histopathology, eosinophils infiltrating into the alveoli and interstitium are present, sometimes forming eosinophilic abscesses.

Treatment of CEP is corticosteroids, often long term because up to 60% of patients relapse. Despite treatment, some patients subsequently develop CSS.

Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia

AEP is a clinical entity with the following features:

- 1.

Fever <5 days

- 2.

Hypoxemic respiratory failure

- 3.

Opacities on chest radiograph

- 4.

BAL with >25% eosinophils

- 5.

Prompt response to corticosteroids, with no relapse after cessation of therapy

- 6.

Absence of parasitic or fungal infection

AEP can be associated with cigarette smoking and tends to occur with a new onset of smoking, restarting smoking, or significantly increasing the amount of smoking less than 1 month before the onset of symptoms. It can also be seen with exposure to dust. A history of asthma is not very common, and there is no gender predilection. Signs and symptoms include rapid development of nonproductive cough, fever, and dyspnea. Most patients go on to develop respiratory failure necessitating mechanical ventilation.

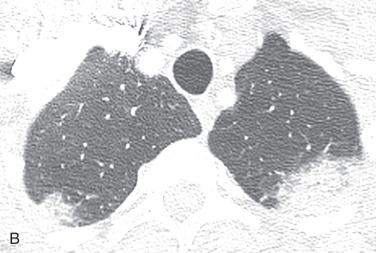

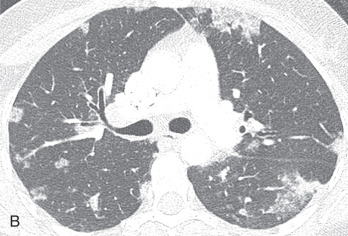

Peripheral blood eosinophilia may not be present early in the disease course. An abnormally high percentage of eosinophils in BAL fluid is characteristic, even reaching 80%. Chest radiography shows reticular opacities, patchy consolidation, and pleural effusion. Chest CT shows patchy ground-glass opacities, consolidation, pleural effusion, and interlobular septal thickening ( Fig. 22.3 ). Small nodules may also be present. On histopathology, diffuse alveolar damage with eosinophils infiltrating mainly into the interstitium is present. The differential diagnosis of AEP includes lung edema, hemorrhage, infection, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. AEP responds to corticosteroids and does not relapse. Survival is close to 100%.

Idiopathic Hypereosinophilic Syndrome

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome is characterized by prolonged peripheral blood eosinophilia (>1.5 × 10 9 /L) of no recognizable cause, persisting for more than 6 months and resulting in organ dysfunction. It is described as a leukoproliferative disorder because of the presence of monoclonal cell populations found in this disease. Also, cytogenetic analysis sometimes reveals a chromosome 4 deletion resulting in a fusion gene called FIP1L1–platelet-derived growth factor receptor α ( FIP1L1-PDGFRA ) fusion gene. Although patients with this FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene are included in the group of those with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, they are considered to have eosinophilic leukemia.

Patients tend to be male and in their third or fourth decade of life. The heart and central nervous system are usually involved. Signs and symptoms include fever, weight loss, neurologic signs and symptoms, including intellectual impairment and neuropathy, and cardiopulmonary signs and symptoms, including cough and dyspnea.

Cardiac complications include endocardial fibrosis, valvular damage, dysrhythmias, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and mural thrombus formation. Lung complications include edema secondary to cardiac failure. Transient patchy consolidation reflecting eosinophilic pneumonia may also be present. BAL fluid shows eosinophilia. On histopathology, affected organs contain eosinophilic infiltration and areas of necrosis.

Chest radiographs can show focal or diffuse septal lines reflecting mild lung edema or areas of consolidation with more extensive edema. On CT, diffuse septal thickening may be present, as well as other findings, including nodules and focal or diffuse ground-glass opacity, which tends to be peripheral. Pleural effusion is common both on radiographs and CT scans.

Treatment of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome includes corticosteroids, cytotoxic drugs, and monoclonal antibodies. FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion protein is present in 50% of patients who respond to a protein kinase inhibitor imatinab. Mepolizumab is another available therapy. Improvements in therapy have decreased the 3-year mortality rate to approximately 4%.

Diseases With a Known Cause

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

ABPA is a hypersensitivity reaction to antigens of Aspergillus spp. ( Aspergillus fumigatus in nearly 90%) and is the most common eosinophilic lung disease, accounting for approximately 75% of patients with pulmonary eosinophilia.

Patients are usually in the second through fourth decades of life and usually have a history of asthma or cystic fibrosis. Aspergillus colonizes the airways and forms mycelial plugs in proximal bronchi. Patients subsequently develop an immune response to the fungi, initially an IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity reaction and subsequently an IgG-mediated type III hypersensitivity reaction. Up to 10% of patients with ABPA also develop allergic fungal sinusitis.

ABPA is usually diagnosed by a combination of clinical and radiographic findings, and biopsy is rarely performed. Diagnostic criteria include asthma, peripheral blood eosinophilia, elevated IgE level, positive skin test for Aspergillus antigens, and pulmonary opacity on radiographs. The serum IgE level is extremely useful and corresponds to disease activity. Common signs and symptoms of ABPA included fever, wheezing, and cough. Some patients will expectorate bronchial casts consisting of fungal hyphae and mucus. Five stages of ABPA have been described by Patterson et al.: acute, remission, exacerbation, steroid-dependent asthma, and fibrosis. In the acute phase, patients have peripheral blood eosinophilia, abnormal chest radiographs, immediate positive skin reaction to Aspergillus antigen, elevated serum IgE, and usually positive serum precipitins against Aspergillus .

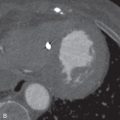

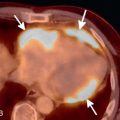

In the acute phase, chest radiography and CT show consolidation, bronchial wall thickening, mucoid impaction, centrilobular nodules, and tree-in-bud opacities ( Fig. 22.4 ). The most common finding is mucoid impaction, which appears as a tubular or branching opacity on chest radiographs and has been described as the finger-in-glove sign. On CT, impacted mucus can be water attenuating, soft tissue attenuating, or hyperattenuating. Chronic findings include proximal bronchiectasis and upper lobe volume loss. Aspergillomas can grow in bronchiectatic cavities. Obstructing endobronchial lesions and bronchial atresia should be considered in the differential diagnosis of ABPA.