Technical Aspects

Anatomy

The esophagus extends from the pharynx to the cardiac portion of the stomach. The length of the esophagus is approximately 25 to 30 cm, and it has cervical, thoracic, and abdominal portions. The cervical portion extends from the cricopharyngeus to the suprasternal notch behind the trachea. The thoracic portion extends from the suprasternal notch to the diaphragm behind first the trachea and then the left atrium. The abdominal portion extends from the diaphragm to the cardiac portion of the stomach.

Imaging

Imaging of the esophagus is challenging because of the location surrounded by many vital organs and poor distensibility of the esophagus. However, recent advancements of multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and workstation and postprocessing techniques have amplified clinical application of computed tomography (CT) in the evaluation of esophageal diseases. These techniques enable coverage of a large volume in a very short scan time. Single breath-hold acquisition with thin collimation and isotropic voxels allows imaging of the entire esophagus with high-quality multiplanar reformation (MPR) and three-dimensional reconstruction. Generally, on CT, the esophagus appears as a well-delineated circular or oval shape of soft-tissue with a thin wall, which is less than 3 mm in a dilated esophagus, but can be thicker in a contracted esophagus. Thus, proper distention of the esophagus (by oral administration of effervescent granules and water) and optimal timing of administration of intravenous contrast material are necessary to detect and characterize esophageal diseases. Compared to endoscopy and double-contrast examination, CT esophagography can provide information on the esophageal wall and the extramural extent of disease. Specifically, MDCT plays a robust role in preoperative staging of esophageal malignant neoplasms. Furthermore, various benign conditions of the esophagus, including rupture, achalasia, esophagitis, diverticula, and varices can be visualized and detected in MDCT.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for esophageal imaging has been technically challenging because of the deep location of the esophagus and the degree of movement related to cardiac motion, peristalsis, and respiration, combined with the relatively slow acquisition time of MRI, which affect image quality. However, recent MRI technology has improved the achievable signal-to-noise ratio, and provides detailed information of the esophagus and the posterior mediastinum with high spatial resolution. High-resolution T2-weighted fast spin echo technique with phased array surface coil can visualize the individual components of the esophageal wall. Cine MRI technique, which can visualize peristalsis of the esophagus, can help staging of esophageal cancer, because interruption of peristalsis reflects impaired muscle function caused by stage T3 or T4 esophageal cancer.

Imaging

Imaging of the esophagus is challenging because of the location surrounded by many vital organs and poor distensibility of the esophagus. However, recent advancements of multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and workstation and postprocessing techniques have amplified clinical application of computed tomography (CT) in the evaluation of esophageal diseases. These techniques enable coverage of a large volume in a very short scan time. Single breath-hold acquisition with thin collimation and isotropic voxels allows imaging of the entire esophagus with high-quality multiplanar reformation (MPR) and three-dimensional reconstruction. Generally, on CT, the esophagus appears as a well-delineated circular or oval shape of soft-tissue with a thin wall, which is less than 3 mm in a dilated esophagus, but can be thicker in a contracted esophagus. Thus, proper distention of the esophagus (by oral administration of effervescent granules and water) and optimal timing of administration of intravenous contrast material are necessary to detect and characterize esophageal diseases. Compared to endoscopy and double-contrast examination, CT esophagography can provide information on the esophageal wall and the extramural extent of disease. Specifically, MDCT plays a robust role in preoperative staging of esophageal malignant neoplasms. Furthermore, various benign conditions of the esophagus, including rupture, achalasia, esophagitis, diverticula, and varices can be visualized and detected in MDCT.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for esophageal imaging has been technically challenging because of the deep location of the esophagus and the degree of movement related to cardiac motion, peristalsis, and respiration, combined with the relatively slow acquisition time of MRI, which affect image quality. However, recent MRI technology has improved the achievable signal-to-noise ratio, and provides detailed information of the esophagus and the posterior mediastinum with high spatial resolution. High-resolution T2-weighted fast spin echo technique with phased array surface coil can visualize the individual components of the esophageal wall. Cine MRI technique, which can visualize peristalsis of the esophagus, can help staging of esophageal cancer, because interruption of peristalsis reflects impaired muscle function caused by stage T3 or T4 esophageal cancer.

Pathologic Conditions

Esophageal tumors include various types of pathologic conditions. We summarized esophageal tumors in Box 18-1 , classifying them into mucosal and submucosal tumors, because these differences closely associate with imaging features of the tumors. For example, typical submucosal tumors appear as a mass with smooth margins on CT and double-contrast examination. Benign esophageal tumors are not common, but sometimes it is difficult to differentiate benign from malignant tumors. Given the high mortality of esophageal cancer, pretreatment diagnosis for esophageal tumors is quite important.

Mucosal

Benign

- •

Adenoma

- •

Squamous papilloma

Malignant

- •

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- •

SCC variant

- •

Spindle cell carcinoma

- •

Basaloid squamous carcinoma

- •

Verrucous carcinoma

- •

- •

Adenocarcinoma

- •

Adenosquamous carcinoma

- •

Neuroendocrine tumor

- •

Submucosal

Benign

- •

Leiomyoma

- •

Cyst

- •

Fibrovascular polyp

- •

Granular cell tumor

- •

Hemangioma

- •

Schwannoma

- •

Lipoma

Malignant

- •

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- •

Sarcoma (leiomyosarcoma)

- •

Lymphoma

- •

Malignant melanoma

Benign Esophageal Tumors

Benign esophageal tumors are not common, representing 20% of esophageal neoplasms at autopsy. Most benign tumors are small and asymptomatic lesions, but some patients may present with dysphagia, bleeding, weight loss, or other symptoms. Benign esophageal tumors are grouped into mucosal and submucosal tumors according to the site of origin. The majority of benign esophageal tumors are located in the middle and lower thirds of the thoracic esophagus, but only fibrovascular polyps arise from the cervical esophagus.

Mucosal Tumors

Squamous papillomas and adenomas are benign esophageal tumors arising from the esophageal mucosa. Squamous papillomas typically occur as solitary polyps in the esophagus and are sometimes difficult to differentiate from early esophageal cancer. The size of the tumors is relatively small, ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 cm, and most patients are asymptomatic. Adenomas are rare polyps in the esophagus, because the mucosa of the esophagus is composed of squamous rather than columnar epithelium. However, esophageal adenomas can arise in metaplastic columnar epithelium associated with Barrett esophagus. Because adenomas have the risk for malignant transformation, endoscopic or surgical resection is necessary. Generally, these tumors are too small to be detected on CT and MRI, but they can appear as small polyps with a smooth or slightly lobulated shape on double-contrast examination.

Submucosal Tumors

In esophageal benign submucosal tumors, leiomyomas are the most common, followed by esophageal cysts.

Leiomyoma

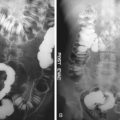

Leiomyomas account for more than 50% of benign esophageal tumors. The tumors are present more often in male patients (2 : 1) at a median age of 30 to 35 years. These tumors arise from smooth muscle and usually are located in the lower two thirds of the esophagus because of the abundance of smooth muscle at this location. Basically, these tumors are slow growing and have a low risk for turning into cancerous tumors. Most of esophageal leiomyomas occur as solitary lesions, but 3% to 4 % of patients are reported to have multiple lesions. Clinically, if the tumor size increases, dysphagia or pain may occur, but most patients are asymptomatic. Treatment options for esophageal leiomyoma may include observation for small tumors that are not causing symptoms and endoscopic or surgical resection. On the double-contrast examination, these appear as a smooth, rounded filling defect forming an obtuse angle with the esophageal wall. On CT, these appear as an intraluminal mass or a wall thickening with smooth peripheral margin, homogenous soft tissue attenuation, and occasional coarse calcification. Sometimes it is difficult to differentiate leiomyoma from esophageal cancer, but leiomyoma is the only tumor that may contain calcification ( Figure 18-1 ). Additionally, absence of imaging features indicating the invasive nature of cancer such as infiltration of the esophageal wall or typical circumferential growth enables differentiation from esophageal cancer.

Esophageal Cyst

Esophageal cysts are the second most common type of benign esophageal tumors. Duplication cysts are more common than inclusion cysts. Duplication cysts usually arise from the lower third of the esophagus, and most of these cysts are located in the right posterior inferior mediastinum and detected in infants or children. Duplication cysts share a muscular wall with the native esophagus and are attached to the esophagus in a paraesophageal or intramural fashion. Duplication cysts are commonly lined by gastric mucosa, and gastric acid produced by this ectopic mucosa may cause complications such as ulceration, hemorrhage, and perforation. Because of these possible complications, surgical removal or enucleation is generally advisable. On the double-contrast examination, the cysts appear as extrinsic or intramural compression because of close contact with the esophagus. On CT, the cysts showed the well-defined, thick-walled structure with fluid, and on MRI these are appreciated as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images ( Figure 18-2 ). Their appearance on CT or MRI is identical to that of bronchogenic cysts; however, the thicker wall and the more intimate contact with the esophagus may be helpful for diagnosis. Technetium-99m sodium pertechnetate scan may be helpful in pediatric patients, in whom 50% of the cysts contain ectopic gastric mucosa.

Fibrovascular Polyp

Fibrovascular polyp is a rare benign submucosal tumor of the esophagus composed of varying amounts of fibrous, adipose, and vascular tissues, accounting for 1% to 2% of benign esophageal tumors. It usually arises from the cervical esophagus and sometimes prolapses into the mouth. It can be a very large tumor with a vascularized thick stalk; thus, surgical resection is the treatment of choice. On CT, attenuation of a fibrovascular polyp shows a wide spectrum, depending on the amount of fibrous and adipose tissue in the tumor. If it predominantly contains adipose tissue, it appears as low (fat) attenuation, which is the typical CT sign of fibrovascular polyp ( Figure 18-3 ). Because of the excellent soft tissue contrast of MRI, it may be helpful in describing the tissue components of the tumor. On T1-weighted imaging, it is appreciated as an intraluminal tumor with high signal intensity, because of its lipid content; it is appreciated as a tumor with low signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Multiplanar MRI also plays an important role in defining the spatial location of the mass.