and Gustavo Marino2

(1)

Attending Physician VA Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

(2)

Chief Gastroenterology Section VA Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

2.1.3 Endobronchial Ultrasound

2.1.5 Mediastinal Biopsies

2.2.1 Mediastinum

2.2.1.1 Aortic Aneurysms

2.2.1.2 Aortic Dissection

2.2.1.4 Subcarinal Lymph Node Biopsy

2.2.1.6 Recurrent Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

2.2.1.7 Bronchial Carcinoid

2.2.1.8 Bronchogenic Cysts

2.2.1.9 Mediastinal Pseudocyst

2.2.1.10 Mediastinal Plasmacytoma

2.2.1.12 Pleural and Pericardial Effusion

2.2.1.13 Consolidated Lung

2.2.1.17 False-Positive PET Scan

2.2.2 Esophagus

2.2.2.1 Carcinosarcoma of the Esophagus

2.2.2.2 T1N1 Esophageal Cancer

2.2.2.5 Esophageal Intramucosal Cyst

2.2.2.6 Esophageal Duplication Cyst

2.2.2.7 Esophageal Leiomyoma

2.2.2.9 Recurrent Esophageal Cancer

2.2.2.10 Challenge Question

Abstract

The esophagus is, from an endosonographer’s perspective, the window into the mediastinum, and it makes sense to consider both anatomic regions together. A good understanding of mediastinal anatomy is a prerequisite for competent image interpretation. After a basic review of cross-sectional and traditional anatomy, the endosonographer should approach mediastinal anatomy from the perspective of the ultrasound transducer in the esophagus. Numerous resources on the Internet allow familiarization of 3-dimensional anatomy of the mediastinum from every possible angle and vantage point, allowing structures and layers to be peeled away and added as desired (see Box 2.1). The number of possible cross sections that can be achieved with linear and radial endosonography probes vastly exceed those that can be reasonably expected to be represented in image collections even if they are dedicated to the topic (e.g., in an endoscopic ultrasound [EUS] anatomy atlas), although these collections are certainly helpful. Therefore, the endosonographer should make a point of identifying mediastinal structures every time an upper EUS exam is being conducted until such time when the mediastinum becomes a “second home.” There is an amusing little book called Flatland that can help condition the brain on how 3-dimensional reality might be reflected in a 2-dimensional plane (see Box 2.1).

2.1 General Principles

2.1.1 The Esophagus: A Window into the Mediastinum

The esophagus is, from an endosonographer’s perspective, the window into the mediastinum, and it makes sense to consider both anatomic regions together. A good understanding of mediastinal anatomy is a prerequisite for competent image interpretation. After a basic review of cross-sectional and traditional anatomy, the endosonographer should approach mediastinal anatomy from the perspective of the ultrasound transducer in the esophagus. Numerous resources on the Internet allow familiarization of 3-dimensional anatomy of the mediastinum from every possible angle and vantage point, allowing structures and layers to be peeled away and added as desired (see Box 2.1). The number of possible cross sections that can be achieved with linear and radial endosonography probes vastly exceed those that can be reasonably expected to be represented in image collections even if they are dedicated to the topic (e.g., in an endoscopic ultrasound [EUS] anatomy atlas), although these collections are certainly helpful. Therefore, the endosonographer should make a point of identifying mediastinal structures every time an upper EUS exam is being conducted until such time when the mediastinum becomes a “second home.”

2.1.2 The Esophagus Is Not a Pipe

Chest radiologists have exquisite knowledge of mediastinal anatomy, and frequent consultation with them is essential for two reasons: (1) to learn and (2) to teach. Almost always it is the radiologist who, as consultant to the original requestor of the chest computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography (PET) scan, makes further recommendations for how a lesion could best be biopsied or further investigated. However, even chest radiologists often have an incomplete understanding of what locations can be successfully biopsied by EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Part of this is related to semantics, for example, mediastinal lymph nodes often are referred to by their relation to the trachea even if they are just as close to the esophagus, and this may already predicate the advice of performing an endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy instead of a transesophageal ultrasound. Furthermore, radiologists are accustomed to static images. How much the esophagus can be displaced in one direction or another by the gentle push from the tip of the echoendoscope is most often not appreciated. Lesions that appear on cross-sectional imaging as if they could not be “seen” or biopsied from a probe in the esophagus are, in fact, often within reach, and some of the cases that follow make this clear.

2.1.3 Endobronchial Ultrasound

There are clearly situations when endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) is the imaging modality of choice in the mediastinum and others where transesophageal EUS is the best modality. In general, EUS is most appropriate for evaluation of the posterior inferior mediastinum, whereas mediastinoscopy or EBUS are best for evaluating the anterior superior mediastinum. In many cases there will be overlap from a purely anatomic point of view. From a clinical standpoint many patients who require biopsies of lesions in the mediastinum will have coexisting pulmonary disease, and biopsies through the esophagus may be preferable to a procedure with a bronchoscope in the trachea or bronchus. The quality of biopsies (false negatives) is also correlated with how much time is available to localize the lesion and find the best biopsy trajectory and the number of biopsy passes that can be made uninterrupted by coughing and other signs of patient distress. Perspectives on the relative merits of EBUS versus EUS from the point of view of gastroenterologists and pulmonologist are listed in Box 2.1.

2.1.4 Lymph Node Maps for the Mediastinum

North American clinicians have traditionally used the Mountain-Dressler thoracic lymph node map. To reconcile differences from the Japanese Naruke system, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer proposed a new lymph node map in 2009 (Box 2.1). The relevant stations for the endosonographer remain the same: upper paratracheal 2L and 2R, lower paratracheal 4L and 4R, aortopulmonary window 5, subcarinal 7, and paraesophageal 8.

2.1.5 Mediastinal Biopsies

Mediastinal lymph node biopsies are relatively easy to perform compared with biopsies of, for example, the pancreas. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has an excellent video describing FNA biopsies of various anatomic locations (see Box 2.1).

2.1.6 Examination of the Esophagus

The examination of small esophageal lesions and high-quality demonstrations of the esophageal wall layers is actually one of the more difficult techniques to master. An overinflated balloon that pushes hard on the esophageal wall will distort the anatomy and may lead to incorrect staging. In contrast to the stomach and rectum, it is not possible to use copious amounts of water to improve acoustic coupling. With patience and practice it is possible to combine moderate balloon inflation and small amounts of water instillation to temporarily view excellent demonstrations of small lesions. If this approach is used, regurgitation and possibly coughing and aspiration are risks. It is, therefore, preferable to elevate the head of the endoscopy table by 30 degrees.

One of the most frequent indications for EUS is the staging of esophageal carcinomas. We assume that most of our readers are familiar with the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) system and the principles of esophageal tumor staging. There are excellent introductory textbooks that deal with this subject matter, and we will not present many esophageal tumor cases here. The problem with correct TNM staging of esophageal tumors is related to not only technical factors or operator experience but also the basic technology. Even with optimal technique there are inherent limitations, and other imaging modalities have caught up so that the contribution of EUS in the preoperative staging of esophageal cancer for surgical resection has been questioned [1]. Leading institutions discourage the restaging of esophageal cancer after combination chemotherapy and radiation [2]. A related but somewhat different problem is the evaluation of small esophageal lesions that are potentially amenable to endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). It was previously thought that this would be an indication where EUS evaluation before the procedure would have the biggest effect. Diagnostic EMR as a first step is increasingly being promoted over EUS evaluation before EMR because the depth of submucosal invasion is difficult to accurately determine using EUS [3]. When submucosal involvement is found the patient is referred for surgical resection because of the high risk of early lymph node metastasis, which would be undetectable by imaging. We still believe that EUS is reasonable before EMR to obtain accurate measurements of the tumor, especially for those practioners who are more comfortable resecting smaller lesions and would refer larger lesions to surgeons with more experience. Furthermore, it seems that EUS will continue to contribute to the optimal management of esophageal cancers. Esophageal tumor length recently has been found to be a strong, independent predictor of long-term survival even when controlled for pTNM criteria in patients with early-stage disease who have not received neoadjuvant chemotherapy [4].

It seems that endoscopy better determines esophageal tumor length than other imaging modalities, and perhaps disease length and tumor volume defined by endoluminal ultrasound could add further value [5].

Box 2.1: Open Access Resources for the Esophagus and Mediastinum

Websites

Anatronica: 3D Interactive Anatomy www.anatronica.com

Articles

Direct Nodal Sampling by Echoendoscopy in Lung Cancer: The Clinician’s Expectations. Insights Imaging 2011 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3259317/

Lung Cancer Staging by Endoscopic and Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration http://is.gd/dm58CC

Mediastinoscopy vs. Endosonography for Mediastinal Nodal Staging of Lung Cancer: A Randomized Trial. JAMA 2010 http://is.gd/vLtRLm

Cancer Staging Poster and Stage Grouping of Lung Cancer, Seventh Edition http://is.gd/X6BAwy

Videos

EBUS Lymph node map: http://is.gd/R6Jaxk

Band Ligation Endoscopic Mucosal Resection of a Distal Esophageal Granular Cell Tumor http://is.gd/cwmBdF

Esophagus – Esophageal cancer EUS example 3 http://is.gd/YFe0ZQ

Esophagus – Adenocarcinoma Arising in Barrett’s Staged with EUS FNA http://is.gd/un1xMr

Mediastinum – EUS of Pericardial Cyst http://is.gd/7Joota

ASGE Learning Video Sample – EUS-Guided Tissue Sampling Techniques: Cytology and Biopsy http://is.gd/6UCGmY

2.2 Cases and Discussions

2.2.1 Mediastinum

2.2.1.1 Aortic Aneurysms

The aorta is typically ignored by endosonographers. However, even transaortic EUS-guided biopsies have been done successfully [6]. Here we demonstrate an aorta with calcified plaques and an aneurysm with clot. Segmental arteries are shown in Chap. 1 (posterior intercostal arteries). The practical point is that transaortic biopsies should probably not be done through a clot/aneurysm or heavily calcified plaque to avoid a showering of cholesterol emboli.

Fig. 2.1

This coronal computed tomography reconstruction shows plaque and clot

Fig. 2.2

This calcified plaque seems to correspond to the lesion seen more distally in the abdominal aorta on the reconstructed computed tomography scan

2.2.1.2 Aortic Dissection

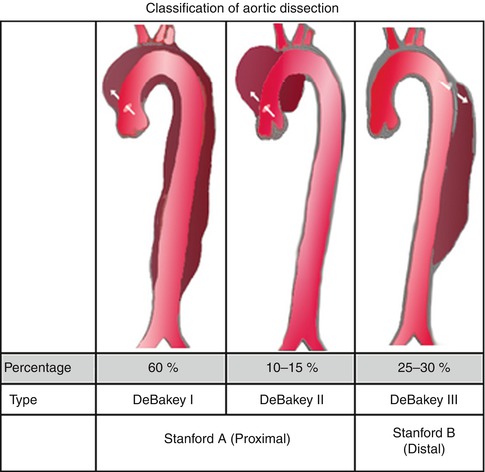

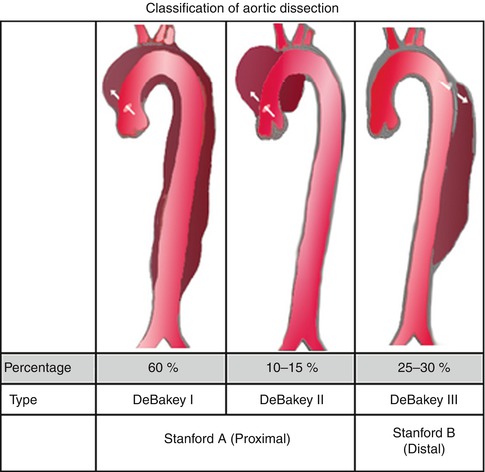

Aortic dissections are infrequently observed during EUS. This is a 74-year-old patient with a type A chronic aortic dissection who was referred for esophageal cancer staging. The DeBakey classification scheme (I, II, or III) is based on the location of the intimal tear and the extension of the false lumen, whereas in the Stanford classification type A indicates involvement of the ascending aorta and type B indicates no involvement of the ascending aorta.

Fig. 2.3

This radial endoscopic ultrasound image shows the thoracic aorta in cross section with two lumina, one of which is false

Fig. 2.4

Power Doppler clarifies the location of the true and false lumen in this type A (Stanford classification) aortic dissection

Fig. 2.5

This is the same aorta as in Fig. 2.4 at the level of the aortic arch. The true lumen is next to the esophagus

Fig. 2.6

Stanford type A means involvement of the ascending aorta, whereas type B indicates no involvement of the ascending aorta (From Wikimedia Commons)

2.2.1.3 New Pulmonary Emboli, Aortic Dissection, and Right Heart Strain

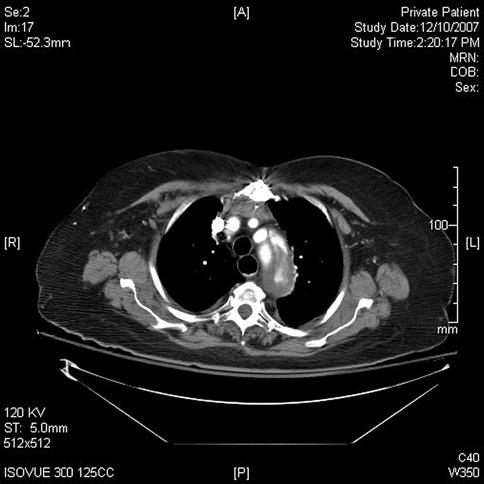

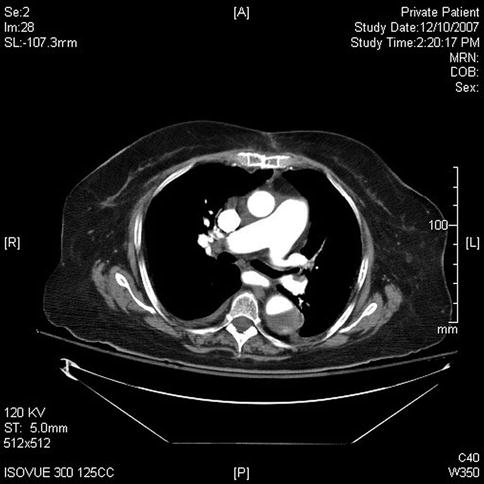

This sequence of images describes pulsatile bidirectional flow in the azygos vein as a sign of right heart strain in the same 74-year-old patient discussed above, who was referred for EUS evaluation of esophageal cancer. Four months earlier she had almost died when she presented with a type A aortic dissection, which was emergently repaired. Doppler EUS shows true and false aortic lumina together with flow in the false channel. To complete staging of her esophageal cancer, a CT scan was done immediately following the EUS exam. CT of the chest revealed new bilateral pulmonary emboli, which were thought to be the likely cause of her disturbed regurgitant azygos flow seen on Doppler endosonography. For didactic purposes the CT scans are shown first, followed by the EUS images. Azygos vein diameters have been correlated with outcomes in cases of pulmonary embolus [7]. Another important and more frequently seen cause of enlarged azygos veins and increased flow rates is, of course, portal hypertension [8].

Fig. 2.7

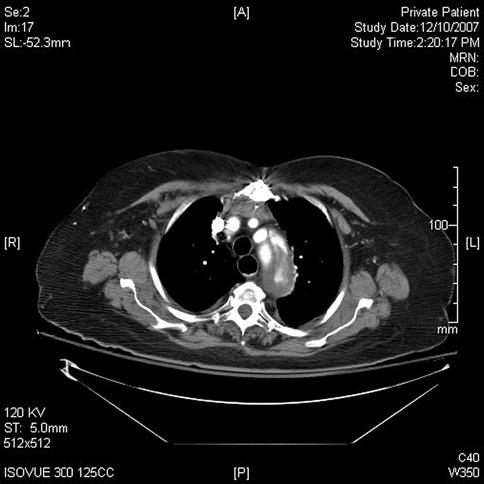

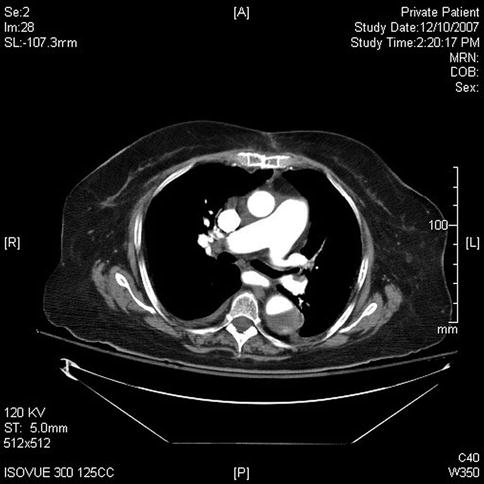

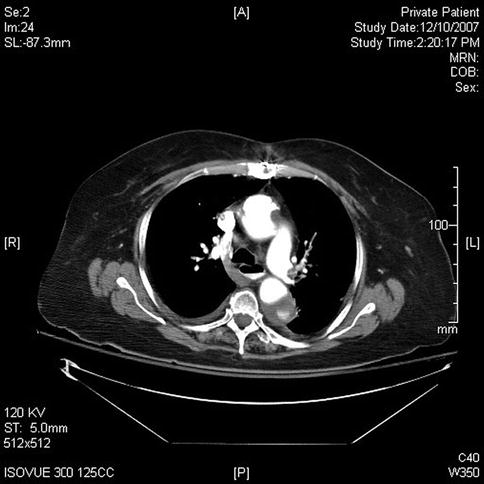

This computed tomography scan shows flow in the true and false lumen in this chronic type A aortic dissection

Fig. 2.8

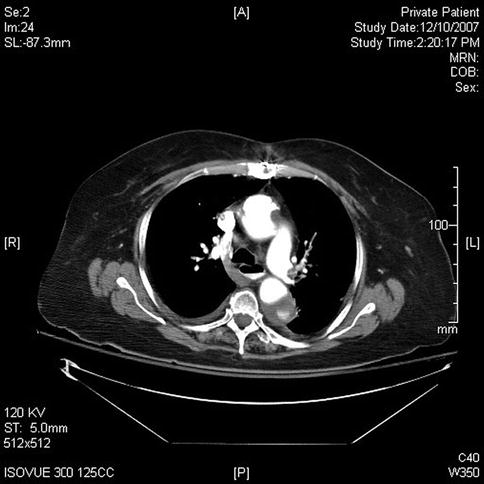

The computed tomography scan performed for esophageal cancer staging shows new bilateral pulmonary artery emboli (only right side shown)

Fig. 2.9

Azygos vein reflux from the superior vena cava is seen on this slice. It commonly represents right heart strain but can sometimes be seen in healthy individuals

Fig. 2.10

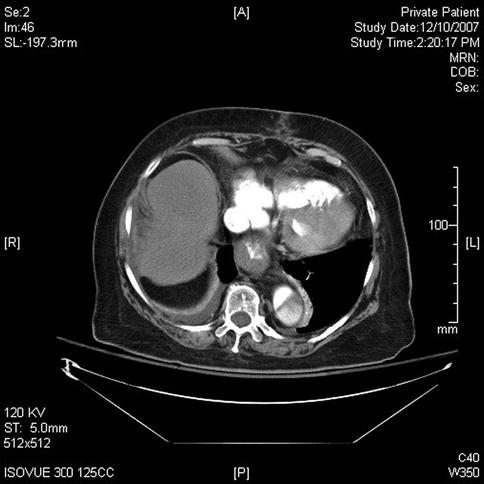

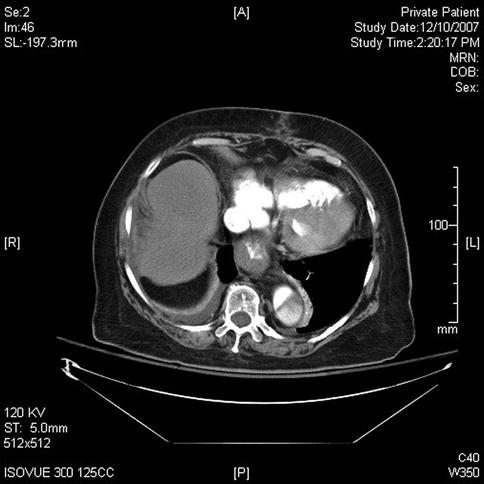

This slice shows thickening of the distal esophageal wall. Note the continuation of the aortic dissection into the abdominal aorta

Fig. 2.11

Endoscopic ultrasound shows a T3 adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus but no apparent lymphadenopathy. A pleural effusion is also present

Fig. 2.12

This image with the GF-UE160 electronic radial echogastroscope shows true and false lumen of the descending aorta and a prominent azygos vein

Fig. 2.13

This endoscopic ultrasound image shows the dissection at the level of the aortic arch

Fig. 2.14

The aortic dissection investigated with power Doppler. The Doppler gate is not positioned to show flow in the false channel

Fig. 2.15

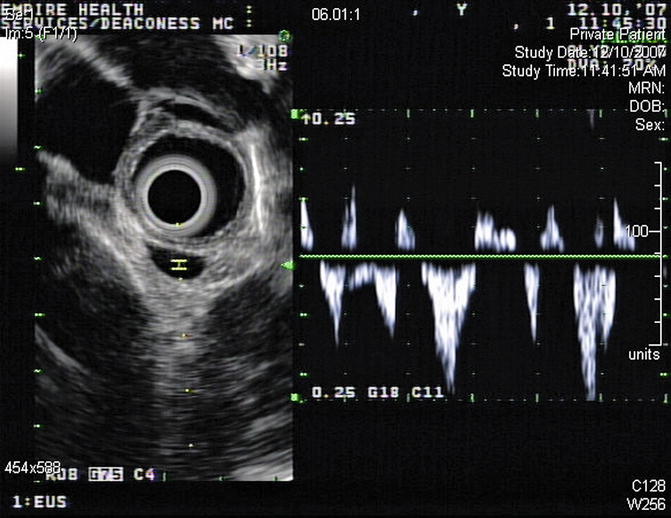

This image shows pulsatile complete reversal of flow in the azygos vein (azygos reflux, bidirectional flow), reflecting right heart strain from the pulmonary embolism

2.2.1.4 Subcarinal Lymph Node Biopsy

EUS-guided FNA has high sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy that is comparable to mediastinoscopy and transbronchial FNA, and it allows sampling of nodes that cannot be easily accessed by other methods. This is a 65-year-old patient who presented 10 months earlier with atelectasis of his left lower lobe of the lung. Noninvasive staging revealed that the cancer was resectable. During surgery it was found to be a T2N1 lesion. Unfortunately, 10 months after the surgery a CT scan of the chest showed a subcarinal lymph node suspicious for recurrent disease. Bronchoscopic evaluation was negative or nondiagnostic. EUS-guided FNA was performed, and cytology confirmed recurrent adenocarcinoma. EUS-guided FNA of American Thoracic Society area 7 (subcarinal) and area 5 (aortopulmonary window) lymph nodes is easy but is unfortunately underused.

Fig. 2.16

Positron emission tomography scan shows the original cancer in the left lower lobe of the lung

Fig. 2.17

Ten months later, subcarinal lymphadenopathy (LN) is seen

Fig. 2.18

Endoscopic ultrasound shows a large partially necrotic lymph node

Fig. 2.19

Fine-needle aspiration

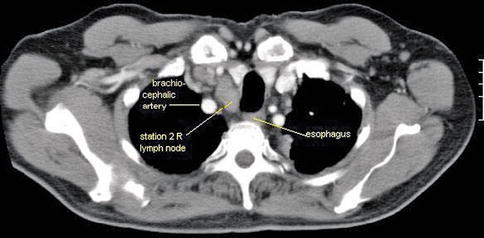

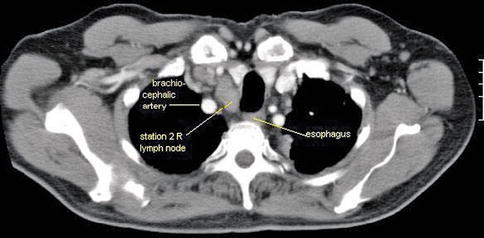

2.2.1.5 Biopsies of Upper Paratracheal Lymph Nodes: Melanoma or Lymphoma?

This is a 74-year-old patient who generally feels well but developed a lump in his neck, which he noticed while shaving. Initial percutaneous FNA biopsy was suspicious for neoplasm but essentially nondiagnostic. A modified radical neck dissection was performed, which revealed the simultaneous presence of mantle cell lymphoma and amelanotic melanoma in the same lymph nodes, confirmed by outside consultation. EUS was performed to biopsy a large right-sided upper paratracheal lymph node to determine whether this station was affected by melanoma or lymphoma. Only lymphoma cells were seen.

Fig. 2.20

This patient with coexisting mantle cell lymphoma and metastatic melanoma found in lymph nodes of the neck also had enlarged upper paratracheal lymph nodes

Fig. 2.21

This is the endoscopic ultrasound view of the 2R lymph node

Fig. 2.22

This initially appeared to be a necrotic cervical lymph 3 cm proximal to the 2R lymph node. The carotid is shown

Fig. 2.23

A closer look at this “lymph node” reveals its irregular features and a surgical drain close by. Given the fact that a neck dissection had jut been performed the day before this EUS, a small hematoma is the most likely explanation

2.2.1.6 Recurrent Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

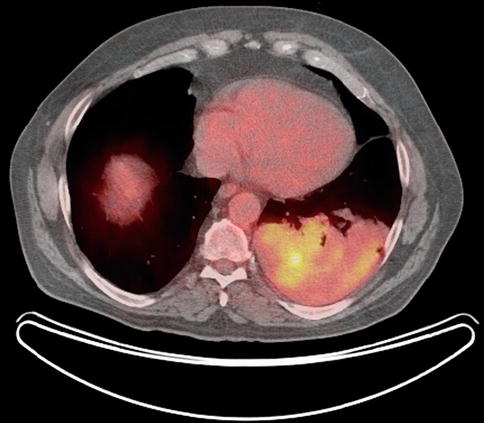

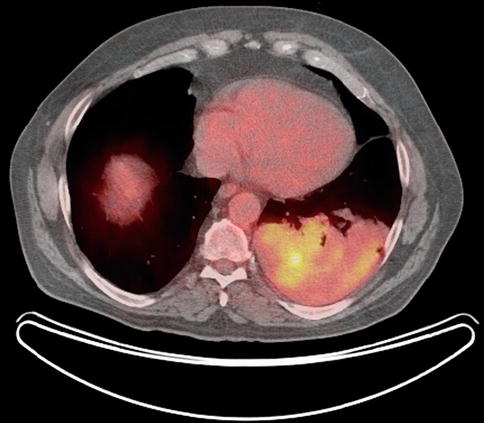

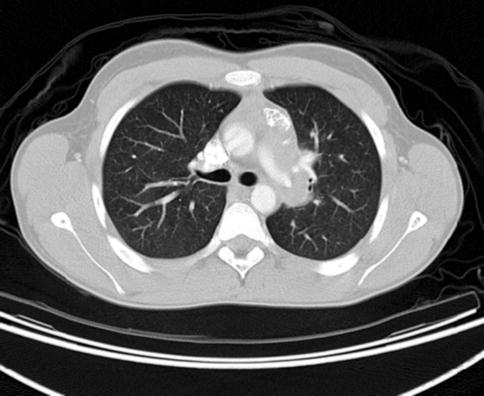

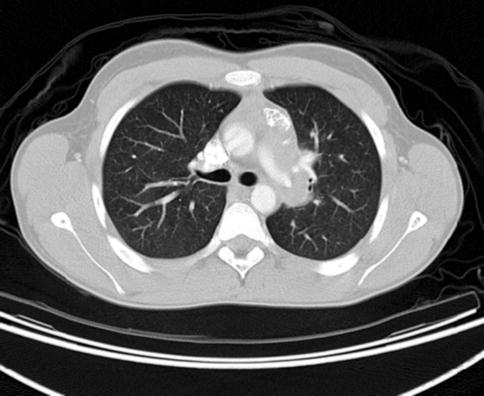

This 14-year-old boy was diagnosed with a nodular sclerosing type Hodgkin’s lymphoma 2 years earlier. He had cervical lymphadenopathy. He finished treatment 6 months later and had a comprehensive follow-up examination 2 years after the first diagnosis. He was feeling well but had several mediastinal hot spots on a positron emission tomography scan. The pediatric oncologist referred him for EUS-guided FNA as the least invasive modality to make a diagnosis. If positive for recurrent disease the patient would need to undergo high-dose chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant. The EUS-guided FNA was positive for two different lymph node groups: subcarinal and aortopulmonary window.

Fig. 2.24

Several hot spots in the mediastinum are suspicious for recurrent Hodgkin’s disease

Fig. 2.25

A computed tomography scan shows a white-out between the subcarina and the spine. Individual structures are difficult to determine

Fig. 2.26

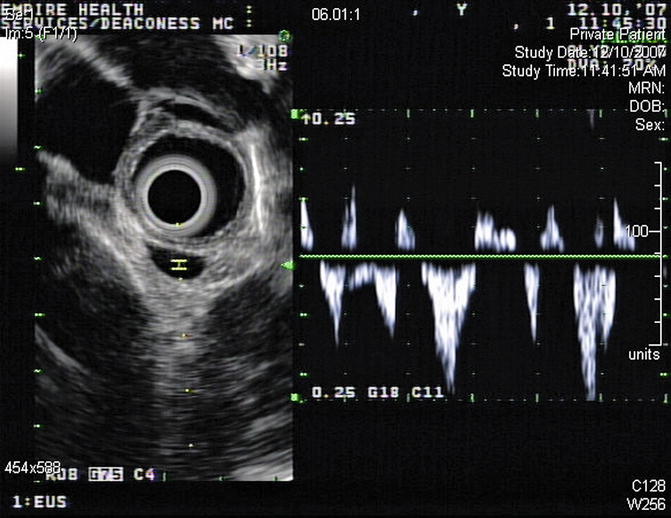

Linear endoscopic ultrasound shows a rather unimpressive subcarinal lymph node with a short-axis dimension of barely 10 mm

Fig. 2.27

This is an enlarged aortopulmonary (AP) window lymph node. Biopsies were difficult and the aspirate repeatedly “dry”

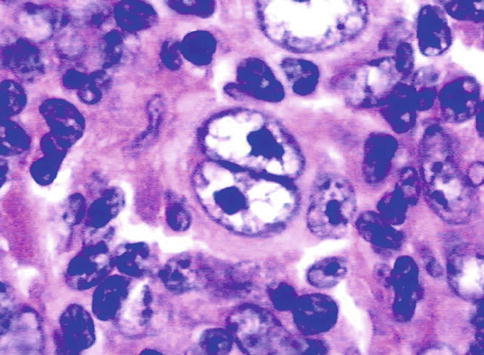

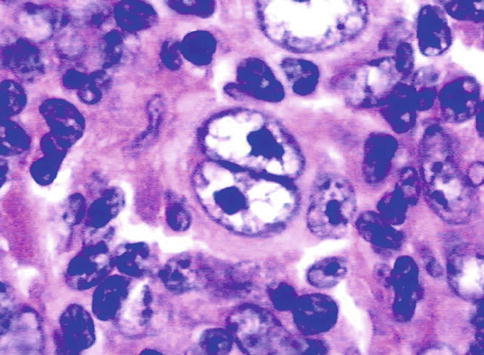

Fig. 2.28

The cytology was positive both for the subcarinal and aortopulmonary window lymph nodes, showing Reed-Sternberg cells and a compatible immunohistochemistry

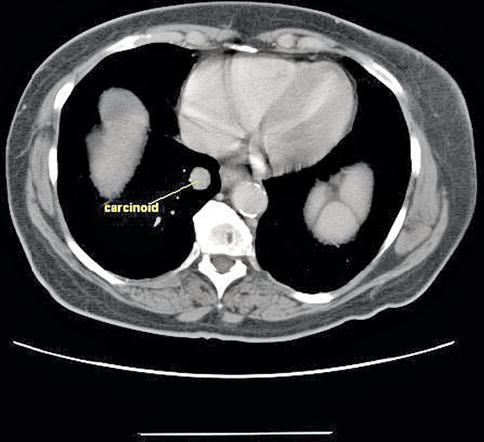

2.2.1.7 Bronchial Carcinoid

This case illustrates the principle that lesions that are distant to the esophagus on static cross-sectional imaging may still be amenable to biopsy through a flexible esophagus. This is a 74-year-old woman with cirrhosis of the liver who was incidentally found to have a centrally located lung tumor on an abdominal CT scan. She was referred for EUS-guided FNA, which revealed cytology characteristic of a bronchial carcinoid. Bronchial carcinoids are tumors that, depending on the subtype, may have relatively low-grade malignant potential associated with slow growth and a corresponding favorable prognosis [9]. In view of the patient’s comorbidities, no further treatment was planned.