Expensive advanced imaging, such as magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, contributes to the unsustainable growth of health care costs in the United States. Evidence-based imaging decreases costs and improves outcomes by guiding appropriate utilization of imaging. Low back pain is an important case illustration. Despite strong evidence that early advanced imaging with MR imaging for uncomplicated low back pain leads to increased costs without significant clinical benefit, MR imaging utilization for acute low back pain has increased. Barriers to evidence-based imaging can be traced to patient- and physician-related factors. Radiologists have a critical role in addressing some of these barriers.

- •

Overutilization of imaging contributes to increasing health care costs.

- •

Evidence-based imaging decreases costs and improves outcomes by guiding appropriate utilization of imaging.

- •

Although evidence-based imaging guidelines recommend against the use of early magnetic resonance (MR) imaging for uncomplicated low back pain, spine MR imaging utilization has increased, often inappropriately.

- •

Barriers to practicing evidence-based imaging, such as in low back pain, include patient- and physician-related factors.

- •

Overcoming barriers to practicing evidence-based imaging requires leadership by radiologists.

Growth of medical imaging

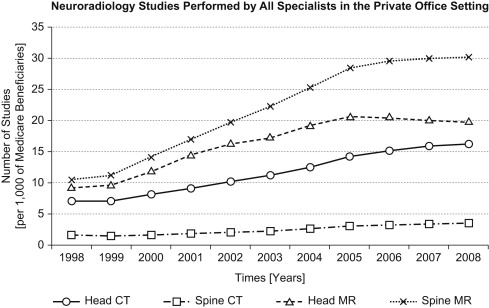

Medical costs in the United States continue to exceed 17% of the Gross Domestic Product each year or more than $2 trillion, greater than any other country. Although computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging are ranked by physicians as the most important innovation to affect their patients, have been recognized through Nobel prizes, and are often celebrated when new units are opened in a community, the proliferation of advanced imaging, more than double the number of units from 2000 to 2008, comes at a high cost. Imaging is one the largest drivers of increasing medical costs. From 1998 to 2005, among Medicare patients the compound annual growth rate for diagnostic imaging was 4.1%. From 2000 to 2009, volume growth of imaging for Medicare patients grew 85%, nearly double the rate for all physician services. For example, in neuroimaging, the volume of spine MR imaging performed for Medicare patients in the private office setting tripled from 1998 to 2008, greater than that for head MR imaging ( Fig. 1 ). This increased utilization and growth of medical imaging is financially unsustainable. Most importantly, approximately 30% of advanced imaging is likely inappropriate and could account for $40 billion of the $480 billion in excess health care expenditures in the United States compared with other countries.

In addition to financial costs of unnecessary imaging, there are health costs including radiation exposure in the case of CT scanning and radiography, associated increased cancer risk, and the consequences of incidental findings. Inappropriate imaging often results in undesirable additional testing and invasive procedures, resulting not only in increased costs but also worse outcomes. Practicing evidence-based imaging can guide appropriate use of imaging, decrease unnecessary imaging-related health care costs, and reduce unnecessary risks to patients.

Low back pain: an opportunity for effective imaging utilization

Low back pain is one of the most common reasons for visits to primary care physicians, with estimated direct medical costs of over $80 billion in 2005. Moreover, the costs of health care related to back pain continue to increase without evidence of a corresponding improvement in self-assessed health status. Part of these escalating costs are due to frequent imaging of patients with back pain, including expensive lumbar spine MR imaging. Given overall increasing health care expenditures, low back pain has been an appropriate target for effectiveness research over the past 2 decades. Appropriate utilization of imaging for low back pain can be optimized by applying evidence-based imaging methods, particularly in the context of comparative-effectiveness research studies, to a technology assessment framework.

Evidence-Based Imaging for Low Back Pain

Evidence-based imaging involves formulating a clinical question, identifying the relevant medical literature, assessing the literature, summarizing the data, and then applying the evidence to make an appropriate clinical decision. Evidence from the most reliable research can be integrated with a physician’s expertise and the patient’s expectations to guide medical decision making regarding which, if any, imaging study is appropriate for a given clinical question. In the context of low back pain, a specific evidence-based clinical question relevant to appropriate utilization would be: in a patient with acute low back pain without evidence of cauda equina syndrome or concern for systemic disease, is early (within 4–6 weeks of symptom onset) lumbar spine MR imaging an effective and appropriate strategy? When evaluating this question, one should use the highest-quality research available, such as prospective, randomized controlled trials, to reduce the potential for bias. Fortunately, there is a reasonable amount of high-quality research focused on low back pain.

Comparative-effectiveness research studies are particularly useful in evaluating appropriate utilization of imaging because they compare the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of existing diagnostic imaging tests. Moreover, differences in the costs of care between the imaging technologies compared are often simultaneously addressed as part of a cost-outcomes study. For example, Jarvik and colleagues conducted a randomized, prospective study in patients with uncomplicated low back pain in a primary care setting by comparing the impact of early lumbar spine MR imaging versus radiographs on disability, pain, preference scores, satisfaction, and costs. Both groups demonstrated improvements in several measures of low back pain disability and pain over time consistent with the natural history of uncomplicated low back pain. Although patients and physicians preferred rapid MR imaging over radiographs, there was no long-term difference in disability, pain, or general health. On the other hand, there was a nonsignificant trend toward increased spine surgery in patients undergoing early MR imaging as well as associated increased costs.

In another randomized, prospective study evaluating outcomes and cost-effectiveness of imaging for low back pain in the primary care setting, Gilbert and colleagues compared the use of early, nonselective MR imaging or CT imaging versus delayed MR imaging or CT in select patients who developed a clear clinical need for imaging. Clinical treatments were similar in both groups, with improvements in back pain; however, there were slightly greater improvements in low back pain and quality-adjusted life year (QALY) estimates with early imaging, which was of questionable clinical significance. Measuring QALY, an indicator of disease burden including both quantity and quality of life, in combination with cost data allows for evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of the 2 imaging strategies. With this information, one can determine whether the additional costs justify the potential small benefit.

Comprehensive Technology Assessment of MR Imaging for Low Back Pain

Whereas evidence-based medicine provides the tools for evaluating evidence related to effective utilization of imaging, technology assessment provides a framework to critically evaluate the comprehensive performance of imaging technologies by addressing a hierarchy of specific questions for a given patient population (for a detailed review see Hollingworth and Jarvik ). For a given technology, such as MR imaging for evaluation of low back pain, the hierarchy of technology-assessment questions that can be addressed using the evidence-based medicine process are outlined in Table 1 .

| Factor | Questions |

|---|---|

| Technical performance | Are the images from a lumbar spine MR imaging technically adequate to reliably evaluate anatomy? |

| Diagnostic performance | Can an accurate diagnosis be made from the MR imaging images? What are the interobserver and intraobserver reliability? What imaging findings on lumbar spine MR imaging could account for causes of low back pain? |

| Diagnostic impact | Does the use of lumbar spine MR imaging change the diagnostic confidence or the use of other testing when evaluating the cause of low back pain? |

| Therapeutic impact | Does lumbar spine MR imaging change clinical management in a patient with low back pain? |

| Health impact | Does the use of lumbar spine MR imaging affect the outcomes of a patient with low back pain? |

| Societal impact | Is the use of lumbar spine MR imaging cost-effective? |

In the context of uncomplicated acute low back pain, there have been many studies that have evaluated these questions for lumbar spine MR imaging. For example, with regard to diagnostic performance and impact, many MR imaging findings, including loss of disc height, disc protrusions, and annular fissures, are so common in patients without back pain that they are nonspecific. Disc extrusions, on the other hand, are uncommon in an asymptomatic population and could be more likely to account for low back pain. The evaluation of therapeutic impact of lumbar spine MR imaging for uncomplicated low back pain, as defined in Table 1 , is often negative because it can lead to unnecessary surgery, as most patients will improve without intervention and regardless of whether they receive advanced imaging. With regard to the health-impact assessment of lumbar spine MR imaging, a patient’s knowledge of nonspecific imaging findings on lumbar spine MR imaging, such as disc protrusions, could negatively affect a patient’s overall sense of well-being. On the other hand, early lumbar spine MR imaging may lead to a slightly greater improvement in pain in comparison with no or late imaging. At a societal level, early lumbar spine MR imaging in the absence of “red flags” for serious conditions is unlikely to be cost-effective.

By applying evidence-based imaging methods to a series of hierarchical questions in this abbreviated example of technology assessment, early MR imaging in uncomplicated back pain does not improve outcomes, leads to increased costs, and can cause negative outcomes such as radiation exposure, for example from additional testing with CT or radiographs, and unnecessary procedures.

Low back pain: an opportunity for effective imaging utilization

Low back pain is one of the most common reasons for visits to primary care physicians, with estimated direct medical costs of over $80 billion in 2005. Moreover, the costs of health care related to back pain continue to increase without evidence of a corresponding improvement in self-assessed health status. Part of these escalating costs are due to frequent imaging of patients with back pain, including expensive lumbar spine MR imaging. Given overall increasing health care expenditures, low back pain has been an appropriate target for effectiveness research over the past 2 decades. Appropriate utilization of imaging for low back pain can be optimized by applying evidence-based imaging methods, particularly in the context of comparative-effectiveness research studies, to a technology assessment framework.

Evidence-Based Imaging for Low Back Pain

Evidence-based imaging involves formulating a clinical question, identifying the relevant medical literature, assessing the literature, summarizing the data, and then applying the evidence to make an appropriate clinical decision. Evidence from the most reliable research can be integrated with a physician’s expertise and the patient’s expectations to guide medical decision making regarding which, if any, imaging study is appropriate for a given clinical question. In the context of low back pain, a specific evidence-based clinical question relevant to appropriate utilization would be: in a patient with acute low back pain without evidence of cauda equina syndrome or concern for systemic disease, is early (within 4–6 weeks of symptom onset) lumbar spine MR imaging an effective and appropriate strategy? When evaluating this question, one should use the highest-quality research available, such as prospective, randomized controlled trials, to reduce the potential for bias. Fortunately, there is a reasonable amount of high-quality research focused on low back pain.

Comparative-effectiveness research studies are particularly useful in evaluating appropriate utilization of imaging because they compare the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of existing diagnostic imaging tests. Moreover, differences in the costs of care between the imaging technologies compared are often simultaneously addressed as part of a cost-outcomes study. For example, Jarvik and colleagues conducted a randomized, prospective study in patients with uncomplicated low back pain in a primary care setting by comparing the impact of early lumbar spine MR imaging versus radiographs on disability, pain, preference scores, satisfaction, and costs. Both groups demonstrated improvements in several measures of low back pain disability and pain over time consistent with the natural history of uncomplicated low back pain. Although patients and physicians preferred rapid MR imaging over radiographs, there was no long-term difference in disability, pain, or general health. On the other hand, there was a nonsignificant trend toward increased spine surgery in patients undergoing early MR imaging as well as associated increased costs.

In another randomized, prospective study evaluating outcomes and cost-effectiveness of imaging for low back pain in the primary care setting, Gilbert and colleagues compared the use of early, nonselective MR imaging or CT imaging versus delayed MR imaging or CT in select patients who developed a clear clinical need for imaging. Clinical treatments were similar in both groups, with improvements in back pain; however, there were slightly greater improvements in low back pain and quality-adjusted life year (QALY) estimates with early imaging, which was of questionable clinical significance. Measuring QALY, an indicator of disease burden including both quantity and quality of life, in combination with cost data allows for evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of the 2 imaging strategies. With this information, one can determine whether the additional costs justify the potential small benefit.

Comprehensive Technology Assessment of MR Imaging for Low Back Pain

Whereas evidence-based medicine provides the tools for evaluating evidence related to effective utilization of imaging, technology assessment provides a framework to critically evaluate the comprehensive performance of imaging technologies by addressing a hierarchy of specific questions for a given patient population (for a detailed review see Hollingworth and Jarvik ). For a given technology, such as MR imaging for evaluation of low back pain, the hierarchy of technology-assessment questions that can be addressed using the evidence-based medicine process are outlined in Table 1 .

| Factor | Questions |

|---|---|

| Technical performance | Are the images from a lumbar spine MR imaging technically adequate to reliably evaluate anatomy? |

| Diagnostic performance | Can an accurate diagnosis be made from the MR imaging images? What are the interobserver and intraobserver reliability? What imaging findings on lumbar spine MR imaging could account for causes of low back pain? |

| Diagnostic impact | Does the use of lumbar spine MR imaging change the diagnostic confidence or the use of other testing when evaluating the cause of low back pain? |

| Therapeutic impact | Does lumbar spine MR imaging change clinical management in a patient with low back pain? |

| Health impact | Does the use of lumbar spine MR imaging affect the outcomes of a patient with low back pain? |

| Societal impact | Is the use of lumbar spine MR imaging cost-effective? |

In the context of uncomplicated acute low back pain, there have been many studies that have evaluated these questions for lumbar spine MR imaging. For example, with regard to diagnostic performance and impact, many MR imaging findings, including loss of disc height, disc protrusions, and annular fissures, are so common in patients without back pain that they are nonspecific. Disc extrusions, on the other hand, are uncommon in an asymptomatic population and could be more likely to account for low back pain. The evaluation of therapeutic impact of lumbar spine MR imaging for uncomplicated low back pain, as defined in Table 1 , is often negative because it can lead to unnecessary surgery, as most patients will improve without intervention and regardless of whether they receive advanced imaging. With regard to the health-impact assessment of lumbar spine MR imaging, a patient’s knowledge of nonspecific imaging findings on lumbar spine MR imaging, such as disc protrusions, could negatively affect a patient’s overall sense of well-being. On the other hand, early lumbar spine MR imaging may lead to a slightly greater improvement in pain in comparison with no or late imaging. At a societal level, early lumbar spine MR imaging in the absence of “red flags” for serious conditions is unlikely to be cost-effective.

By applying evidence-based imaging methods to a series of hierarchical questions in this abbreviated example of technology assessment, early MR imaging in uncomplicated back pain does not improve outcomes, leads to increased costs, and can cause negative outcomes such as radiation exposure, for example from additional testing with CT or radiographs, and unnecessary procedures.

Summary evidence-based resources

Finding and evaluating evidence-based medicine methods can be time consuming, particularly when there is an extensive body of primary research literature such as for imaging in low back pain. Summary evidence-based resources, such as systematic reviews, appropriateness criteria, and clinical guidelines, are tools that summarize and evaluate the supporting evidence to facilitate the practice of evidence-based imaging and effective utilization.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Systematic reviews aim to reduce bias when evaluating a specific topic by using the evidence-based medicine process to exhaustively identify, assess, summarize, and synthesize findings from all relevant studies. Using specialized statistical methods, primary data from selected studies can be synthesized quantitatively as part of a meta-analysis to evaluate potential bias and increase statistical power. For example, Chou and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the use of early imaging for low back pain in patients without indication of serious underlying conditions versus usual clinical care without early imaging. Their literature searches identified more than 450 potentially relevant articles; on further assessment of these articles, 6 randomized trials of sufficient quality were identified comparing early imaging using radiographs, CT, and/or MR imaging versus no early imaging in the evaluation of low back pain. A meta-analysis was then performed by combining the primary data from several of these 6 studies. The investigators found that early imaging does not improve short-term or long-term outcomes for pain, function, quality of life, mental health, or a measure of overall improvement in the health of patients with uncomplicated low back pain.

Appropriateness Criteria

Whereas systematic reviews and meta-analysis help to facilitate the process for evaluating effective use of imaging by synthesizing a large body of evidence, appropriateness criteria and clinical guidelines provide more practical recommendations regarding effective use of imaging.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria were first developed in the early 1990s to help guide the appropriate use of imaging. There are currently 17 major neuroradiologic imaging topics ( Box 1 ) that are addressed including low back pain, headache, and head trauma. For each of these larger topics, the guidelines are further subdivided into various clinical scenarios. For example, in low back pain 6 clinical variants are addressed, as outlined in Box 2 . For each of these clinical scenarios different radiological procedures, such as MR imaging, CT, myelography, radiography, and bone scans, are rated on a scale of 1 to 9 based on their determined appropriateness, with 9 being “usually appropriate.” A committee of experts assigns appropriateness ratings based on individual interpretations of the relevant literature until consensus is reached using a modified Delphi technique. In the case of uncomplicated, acute low back pain, without red flags to suggest more serious causes of low back pain, as defined in Box 3 , all reviewed imaging modalities, including lumbar spine MR imaging, were rated a 2 and considered “usually not appropriate.” On the other hand, when systemic disease such as infection or cancer is suspected, lumbar spine MR imaging is rated an 8 and considered “usually appropriate” ; the appropriateness ratings for other imaging tests in this clinical scenario are summarized in Fig. 2 .