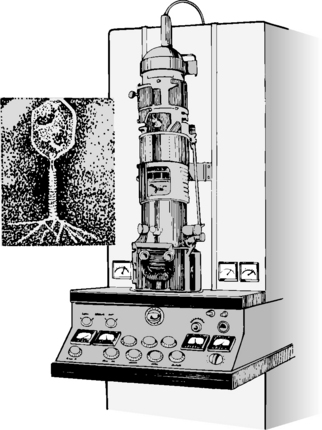

CHAPTER 4 On completion of this chapter, you should be able to: • List the main contributions to medicine from ancient Egypt, India, China, and Greece. • Describe the medical practice of the ancient Hebrews. • Outline the teachings of Hippocrates. • Describe the effect of Christianity on medicine. • List events during the Renaissance that were significant in the progress of medicine. • Describe important advances in medicine from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. • List the significant developments in medicine during the twentieth century. • Indicate trends in medicine for the twenty-first century. • Describe the major issues in medicine at the present time. • List the top 15 causes of death in the United States. • Compare mortality rates among various groups. • List the primary disabling conditions present in U.S. society. • List diseases that have been eradicated or are targeted for elimination. • Explain the significance of emerging infectious diseases. • List key social forces that affect the health care system. • Discuss the dominant ethical issues in medicine today. • Explain the impact of an aging population on health care delivery. • Describe the nation’s health care expenditures. • Explain prospective payment. • Correlate defensive medicine, medical malpractice, and health care costs. • Give the top five causes of death, and list the associated risk factors. • Describe a typical wellness program. • Describe the advantages of giving up smoking. • Link poor diet to major causes of death. • Outline dietary guidelines for good health. • Discuss the role of the radiologic technologist in patient education. • List alternate health care practices. Until well into the nineteenth century, medical treatment was intertwined with religion and magic (Fig. 4-1). Some cultures treated their sick, elderly, and disabled with kindness. Other cultures, during times of famine, sent the elders out into the unsheltered environment; some even killed and ate disabled tribe members. Disease was thought to be caused by gods and spirits, and magic was used to drive away evil forces. Tribal healers held high political and social positions and were responsible for performing religious ceremonies and protecting the tribe from bad weather, poor harvests, and catastrophes. Along with sucking, cupping, bleeding, fumigating, and steam baths, medicinal herbs were used to treat wounds. Surgery was used to treat bone fractures and to sew up wounds. The Mesopotamians studied hepatoscopy, which is the detailed examination of the liver. They believed the liver was the seat of life and the collecting point of blood. Although gods and magic still played an important role in medicine, rational thought about nature’s relationship to health began to increase. FIGURE 4-1 Magic and religion played an important role in medicine well into the nineteenth century. In ancient China, harmony was considered to be a delicate balance between yin and yang, and Tao was considered the way. Illness was seen as a result of disregard for Tao or acting contrary to natural laws. Chinese medicine focused on the prevention of disease (Fig. 4-2). Because Confucius forbade any violation of the body, dissections were not performed in China until the eighteenth century. According to Nei Ching, five methods of treatment were available: cure the spirit; nourish the body; give medications; treat the whole body; and use acupuncture and moxibustion, which is a treatment similar to acupuncture in which a powdered plant is burned on the skin. Treatment came in the forms of exercise, physical therapy, massage, and administering medicinal herbs, trees, insects, stones, and grains. By the eleventh century, the Chinese had developed an inoculation against smallpox. “He employed few drugs and relied largely upon the healing powers of nature…. The treatment of disease for him was to assist and, above all, not to hinder nature. If succeeding generations had followed his precepts, patients would have been spared countless unnecessary operations and an enormous number of nauseous, disgusting, ineffectual and frequently harmful medicines” (Major, 1954). The seventeenth century was an age of scientific revolution. Latrochemistry, a combination of alchemy, medicine, and chemistry, was practiced by the followers of Paracelsus. Jan Baptista van Helmont made the first measurement of the relative weight of urine by comparing its weight with that of water. Galileo presented the laws of motion in a mathematical manner that could be applied to life on earth; Isaac Newton discovered gravity. William Harvey found that a continuous circulation of blood was present in a contained body system. Christian Huygens developed the centigrade system of measuring temperature; Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit developed the system named after him for measuring temperature. Marcello Malpighi and Anton van Leeuwenhoek were forerunners in the invention of the microscope (Fig. 4-3). Quinine was discovered as a treatment for malaria. Leonardo da Vinci explored human anatomy through dissection; his anatomic sketches disseminated his findings. November 8, 1895, is a date that forever changed the course of diagnoses of disease and injury. As will be explained more fully in Chapter 5, Wilhelm Roentgen discovered and described x-ray films. Within months, the significance of these new kinds of rays in medicine was realized. Pierre and Marie Curie discovered radium 3 years later and provided the foundation for the use of radioactivity in the treatment of diseases. Surgical techniques were refined, and diagnostic procedures became more accurate. The invention of the electron microscope in 1930 (Fig. 4-4) made possible the study of viruses and advances in the fields of biochemistry, biophysics, physical chemistry, and immunology. The second millennium ad continues with a rapid expansion of technology and information. The accumulation of knowledge accelerates at an unprecedented pace, doubling every 15 to 18 months. Balancing this technologic explosion in medicine, a trend has emerged toward a more personal aspect of health care. The need for the human touch, caring, and concern has never been more important. More personal aspects of care such as the hospice movement for the terminally ill and the reemergence of family practice as a specialty are but a couple of examples (Fig. 4-5). As you begin your studies in this intriguing profession, keep in mind that the human aspect of patient care and quality service must be ever present in your practice.

Evolution of Health Care Delivery

Prehistoric and ancient medicine

Ancient China

Ancient Greece

Hippocrates

The Renaissance

Nineteenth century

Twentieth century

Twenty-first century

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine