EYE: NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

KEY POINTS

- The imaging findings in eye inflammations are often nonspecific.

- Imaging can identify findings that aid in the differential diagnosis or causative pathology in a minority of patients.

- Imaging may help differentiate noninfectious inflammatory conditions from tumor and infection, but imaging sometimes complicates that process and leads to the mistaken belief that a tumor or infection is present.

- Imaging can identify complications such as effusions and detachments that may lead to improved outcomes if treated promptly.

The eye has several coats and internal ocular spaces that can become involved with either acute or chronic inflammatory disease. These inflammations can then cause episcleritis, scleritis, and uveitis. The reactive layer of most interest is the uveal tract. The term endophthalmitis can be applied when the inflammation affects at least one coat of the eye and an adjacent ocular cavity. Endophthalmitis, however, is generally accepted as a term that is consistent with a very serious infection of the eye seen postoperatively or one that is seeded by a systemic infection, and the term should best be used in that sense. Despite that most common usage, endophthalmitis is a term that can be properly used to describe an inflammatory and reactive noninfectious process if desired.

Noninfectious inflammatory diseases may be local or related to systemic disease.

These inflammatory diseases can be complicated by hyaloid, choroidal, and retinal detachments discussed in Chapter 45 and related collections of blood and fluid discussed with regard to their basic appearance on imaging studies in Chapter 10.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

The anatomy of the eye is discussed in detail in Chapter 44. A working understanding of the coats and spaces of the eye and surrounding preseptal and postseptal soft tissues is useful in analyzing eye infections. The anatomy related to the choroid, retinal, and hyaloid membrane of the eye and various detachments and fluid collections related to these structures that could result from inflammatory conditions are discussed in Chapter 45.

The main vascular tissue in the eye is the uveal tract and outside the eye the conjunctiva. It is important to understand that these anatomic structures essentially envelop the eye inside and out with a slow-flow, highly vascular membrane. It should not be surprising that inflammation that is triggered by immune complexes and/or associated with vasculitis is often initially and predominantly expressed in these structures.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The eye is studied with ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance (MR) techniques described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45. These noninfectious inflammatory conditions may be seen coincidentally on images of the brain and face done for other purposes and, therefore, on images with much lower resolving power than those that might be focused on the eye.

Dedicated studies of the eye/orbit must be done with the highest possible resolution given other constraints on the anatomy that need to be evaluated. Often, a separate protocol for the eye and orbit is required if both the brain and eye/orbit must be studied definitively.

Pros and Cons

CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are generally not indicated in episcleritis and scleritis, but those conditions may be seen if these studies are done to distinguish these superficial inflammatory conditions from more extensive inflammation. The signs of uveal tract inflammation seen on CT and MRI are nonspecific findings. These patients are usually not imaged for evaluation of uveitis, but that inflammation may provide clues about the nature of related sinonasal and intracranial abnormalities or suggest systemic disease.

CT and/or MRI may be used to evaluate chronic inflammatory conditions of the eye that mimic other diseases and in which the funduscopic examination may not be definitive.

US may not be possible in a painful, inflamed eye; however, it may be useful in a nonpainful, chronically inflamed eye, especially to identify signs of an unsuspected infection or more commonly identify detachments and related fluid collections or effusions that can be repaired and drained, thus contributing to a better outcome.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Ocular Noninfectious Inflammatory Conditions

Etiology

Inflammations can be local or part of a systemic process. These include mainly diseases that likely are some triggered aberrant immune response. These autoimmune diseases (Chapter 20) include rheumatoid arthritis, the seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and Behçet disease, among others, that are far beyond the scope of this resource. Other diseases of poorly understood specific origin but likely having an aberrant immune mechanism include sarcoidosis (Chapter 18), Wegener granulomatosis (WG) (Chapter 17), and rarely Langerhans histiocytosis (Chapter 19). A periscleritic form of pseudotumor is also possible.

When eye findings are seen on imaging examinations of the face and neck, concomitant orbital sinonasal or intracranial findings may provide clues to a systemic origin.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These tend to be sporadic inflammatory conditions except when clearly linked to a population with known autoimmune diseases. They occur in both the pediatric and adult populations.

More specifics with regard to these issues are discussed in chapters dedicated to those diseases as indicated in the previous section on etiology.

Clinical Presentation

These inflammatory conditions typically present with a red and swollen eye that is usually painful. There will typically be evidence of uveitis, including anterior and/or posterior (vitreous) intraocular cells that can be visualized by slitlamp examination.

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

The pathophysiology of inflammatory conditions and their appearance on imaging studies is discussed in general in Chapter 13.

The main vascular tissue in the eye is the uveal tract and outside the eye the conjunctiva. It is important to understand that these anatomic structures essentially envelop the eye inside and out with a slow-flow, highly vascular membrane. It should not be surprising that inflammation that is triggered by immune complexes and/or associated with vasculitis is often initially and predominantly expressed in these structures.

Episcleritis is inflammation of the tissue between the conjunctiva and sclera, and scleritis is an inflammation of the sclera itself. These entities may coexist.

Scleritis and episcleritis are manifest by thickening and enhancement of the scleral margin and edema of surrounding fat. In posterior scleritis, fluid may be visible in the Tenon space, and there may be associated choroidal detachment. Other detachments are possible as well. Scleral perforation is rare; staphylomas may form at areas of scleral weakening.

Some inflammatory processes, just like infections, produce primarily a chorioretinitis.

Manifestations and Findings

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

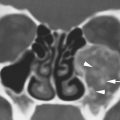

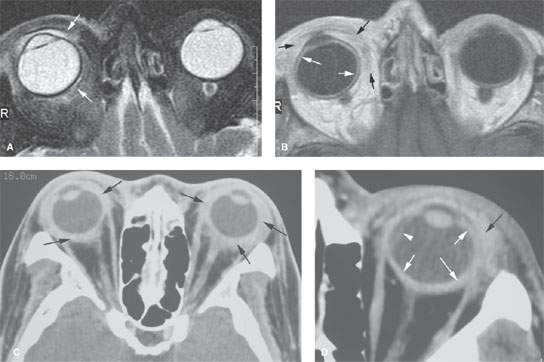

Scleritis and episcleritis are manifest by thickening and enhancement of the scleral margin and edema of surrounding fat, which usually is easily seen on contrast-enhanced CT and best seen on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat-suppressed and T2-weighted fat-suppressed images (Figs. 50.1–50.3). In posterior scleritis, fluid may be visible in the Tenon space, and there may be associated choroidal detachment (Chapter 45) (Fig. 50.4). Scleral perforation is rare; staphylomas (Chapter 46) may form at areas of scleral weakening.

The thickening and enhancement of the choroid, ciliary body, and/or iris seen on contrast-enhanced CT and best on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images are nonspecific findings. These patients are usually not imaged for evaluation of their uveitis. When focal, such changes can be mistaken for tumor (Fig. 50.2A).

Findings consistent with uveitis are often encountered on scans done for central nervous system (CNS) symptoms with the involvement of the uveal tract being noted as an additional manifestation of disease—for example, cytomegalovirus uveitis seen in AIDS patients studied for CNS complaints.

FIGURE 50.1. A, B: Magnetic resonance imaging study on a patient with severe allergic conjunctivitis. The patient presented with painful inflammatory-appearing chemosis of uncertain etiology. The study was done mainly to look for an infectious cause. The purpose of the illustration is to show the relationship of the two main vascular coats of the eye, the conjunctiva, and uveal tract. This was eventually proven to be due to an allergy produced by atropine in an eye drop installation. In (A), the T2-weighted image shows edema within the conjunctival sac and periscleritic edema (arrows). In (B), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image show extensive periscleritic inflammation surrounding the eye and within the conjunctival sac (black arrows). There is also excessive enhancement of the uveal tract (white arrows). C: Contrast-enhanced CT study of a different patient with extensive, bilateral periscleritic swelling. The bilateral disease suggests a systemic process. This was due to autoimmune disease. D: Contrast-enhanced CT study showing a third patient with extensive soft tissue swelling around the eye, especially laterally (black arrow). There is also excessive thickening along the uveal scleral margin (white arrows). There is a small choroidal detachment (arrowhead). (NOTE: This was felt to likely be infectious endophthalmitis; however, it turned out to be related to autoimmune disease even though the findings were unilateral.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree