FACIAL NERVE: BENIGN TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography are commonly performed to look for abnormalities of the facial nerve.

- Pathology in the facial nerve region may be diverse, but the vast majority of cases are straightforward diagnostic situations.

- The acute onset of a peripheral facial nerve palsy may not require magnetic resonance or computed tomography study unless there is reason to believe there is an underlying infectious (other than viral) cause that must be treated with haste.

- Peripheral facial nerve palsy that presents with a different timetable, recurs, or does not recover requires very detailed magnetic resonance and computed tomography studies of the facial nerve to search for a structural lesion that is very likely present in those atypicalsettings for Bell palsy.

- Atypical presentations of peripheral facial nerve palsy may be due to a specifically treatable benign mass of the facial nerve, one that is compressing but not arising from the nerve, or infectious and noninfectious inflammatory or malignant neoplastic diseases.

- Imaging can be very helpful to triage patients with peripheral facial nerve palsy to the next best step in the diagnostic process.

Facial nerve–origin neurogenic tumors account for about half of the benign masses that arise from or immediately around the facial nerve. Hemangiomas constitute most of the other half and are discussed in Chapter 132 along with other vascular lesions that affect the facial nerve. Other benign conditions that affect the nerve will spread from contiguous skull base sites and intracranial sites, most commonly in the internal auditory canal (IAC) and cerebellopontine angle (CPA) and possibly from the cochleovestibular nerve (CVN).

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

The computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) anatomy of the facial nerve must be completely understood, including its brain stem nucleus, its course through the brain stem, its cisternal segment, its course through the IAC and entire facial canal, and its entire course and distribution beyond the stylomastoid foramen. This anatomy is presented in detail in Figures 104.51–104.54, 175.8, 175.9, 175.15, and 175.16 as well as in Chapters 104 and 175.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

MRI and CT in this anatomic region almost always requires the highest possible spatial resolution. These issues are discussed in detail in conjunction with general CT and magnetic resonance (MR) parameters (Chapters 1–3). Specific protocols for MR and CT studies for investigating facial nerve problems in general appear in Appendixes A and B. Any such MR study must include provision for a three-dimensional steady state acquisition with nominal section thickness #1 mm that can be analyzed in any plane. The same type of CT data analysis is necessary.

The facial nerve is typically studied with dedicated contrast-enhanced studies of the temporal bone, especially when the facial weakness or hemifacial spasm is of slow onset, progressive, or recurrent.

Facial nerve studies most safely include the entire peripheral course of the facial nerve as well as the posterior fossa when the etiology is uncertain. If suspicious for subtle findings or when symptoms are progressive with previously negative imaging studies, these studies may needed to be repeated at clinically reasonable intervals.

Pros and Cons

MRI should be done first, as it most confidently excludes causative pathology of all facial nerve segments (i.e., the brain stem, cisternal, exit canal/foramen, and extracranial segments) from its brain stem nucleus to the parotid gland. MRI is more sensitive than CT for excluding intra-axial pathology such as demyelinating disease, pia-arachnoid diseases (Chapters 129 and 131), and small neoplasms of the nerve that might involve the cisternal segment or the segment within the IAC as well as perineural spread of cancer (Chapter 131).

CT may be done as a supplement to most confidently exclude similar pathology within the facial canal from the labyrinthine segment to the stylomastoid foramen and beyond the parotid gland distally. This supplemental imaging may be done as a routine study or only when MRI findings are suspicious for a lesion other than inflammatory enhancement. Supplemental CT is done when the onset of symptoms is strongly suspicious for a facial nerve lesion and the cause is not established by MRI or the MRI is suspicious for a cause but not definitive. For benign tumors of the intratemporal course of the facial nerve, CT may be especially helpful for showing erosive patterns of bone or subtle bony spiculations within the lesion that help to distinguish a likely schwannoma from a potentially mimicking hemangioma (Chapter 132).

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Benign Neurogenic Tumors of the Facial Nerve

Etiology

Benign neurogenic tumors associated with classic neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 or NF type 2 make up a small percentage of these usually sporadic occurring tumors of the facial nerve. Histologically, tumors may be found to be consistent with plexiform neurofibromas without other NF-1 or NF-2 stigmata. Otherwise, these lesions are sporadic and very uncommon.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These are very uncommon tumors that may be found incidentally at autopsy. These occur with no particular gender predilection and tend to present in the younger adult years.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms depend on the site of origin and extent of the lesion. Patients with a facial schwannoma will generally present with slowly progressive peripheral facial nerve weakness, recurrent facial palsy associated with spasticity, or hemifacial spasm alone. Occasionally, the schwannoma will be found incidentally during evaluations for unrelated problems such as headache and the facial nerve function may be normal.

Extension to the middle ear may cause conductive hearing loss. Further growth may lead to inner ear symptoms or a mass bulging into the external auditory canal. If the greater superficial nerve is involved, tearing may be abnormal. Involvement of the chorda tympani may cause a palatal sensory deficit and altered taste. Tumors of the IAC or CPA will often have accompanying eighth cranial nerve symptoms. Patients with intraparotid schwannomas of the facial nerve will typically present with a painless, slow-growing mass and normal facial nerve function. Unlike schwannomas, peripheral neurofibromas have not been reported to cause facial nerve dysfunction.1–5

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

Nerve sheath tumors will most commonly arise along the facial nerve intratemporal segment, usually somewhere between the labyrinthine portion and the descending facial canal (Figs. 130.1–130.3). These lesions might extend to the labyrinthine segment and canalicular segments but are usually diagnosed before such extension has occurred unless they have arisen in the IAC or the labyrinthine segment (Fig. 130.4). Distal nerve sheath tumors may arise beyond the stylomastoid foramen along the main trunk of the nerve within the parotid gland; this is a less common site of origin than the intratemporal course of the nerve. More distal origins are distinctly rare.

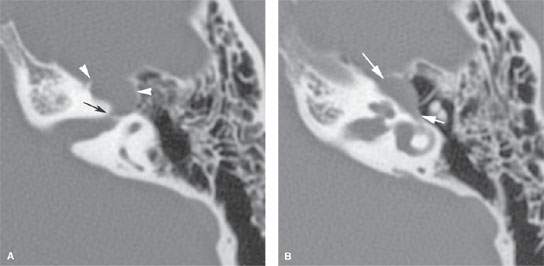

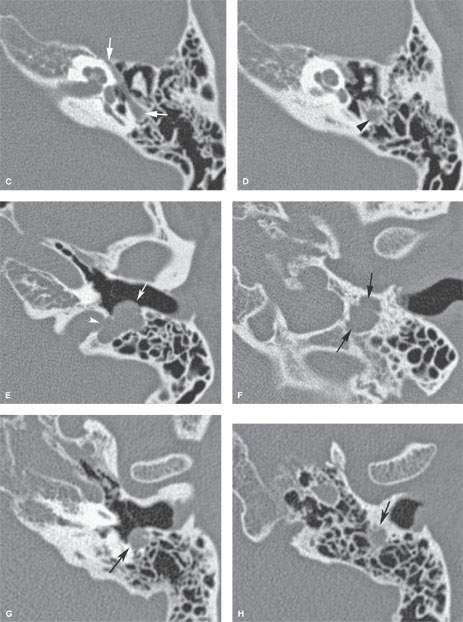

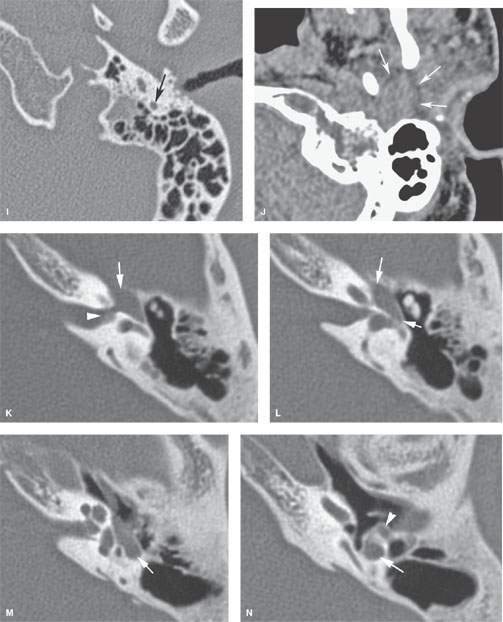

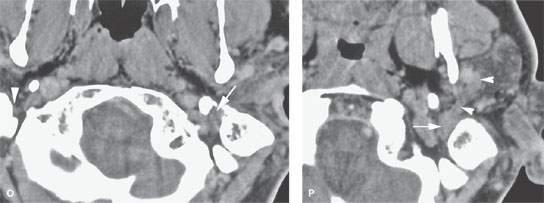

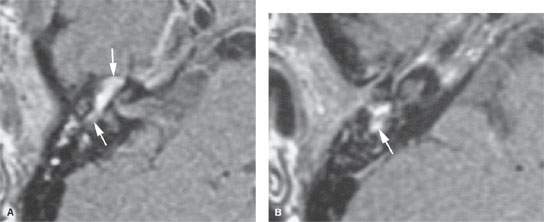

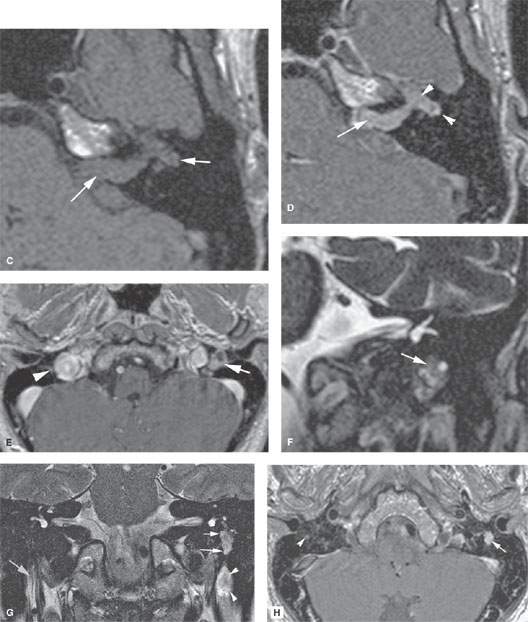

FIGURE 130.1. Several patients demonstrating computed tomography (CT) findings of benign nerve sheath tumors of the facial nerve. A, B: Patient 1. Facial nerve schwannoma causing focal enlargement of the proximal tympanic segment and at the anterior genu (arrowheads) with bone erosion as well as widening of the labyrinthine facial nerve canal segment (arrow). C–F: Patient 2. Facial nerve schwannoma with the tympanic segment of the facial nerve appearing normal on axial images (C). A lobulated mass is present along the mastoid segment, causing remodeling of the surrounding bone and erosion of the posterior wall of the external auditory canal (EAC) (arrow) and of the jugular plate (arrowhead) (D–F). The patient presented with tinnitus; on inspection, bulging of the posterior wall of the EAC was seen. The facial nerve function was normal. G–J: Patient 3. Facial nerve schwannoma with a dumbbell appearance (refer to Fig. 130.2G–J) manifesting as enlargement of the mastoid segment with erosion of the posterior EAC wall (G). In its mid mastoid segment, the schwannoma extends into surrounding mastoid air cells, causing irregular margins (H). More distally, the facial nerve canal appears normal (I). The extratemporal nodular component might be overlooked on contrast-enhanced CT. K–P: Patient 4. Facial nerve neurofibroma showing the slow-growing tumor causes in regressive remodeling of bone along the labyrinthine segment and anterior genu as well as the greater superficial petrosal nerve (K), tympanic (L, M), and mastoid (M, N) segments. The extension beyond the stylomastoid foramen and in the parotid is best seen on postcontrast images (O, P).

FIGURE 130.2. Several patients to illustrate the magnetic resonance findings and localizations of benign nerve sheath tumors of the facial nerve. A, B: Patient 1. Facial nerve neurofibroma with focal enlargement and homogenous enhancement of the tympanic segment. Neurofibromas may, however, lack enhancement. C, D: Patient 2. Facial schwannoma extending from the cisternal segment to the tympanic segment (arrows in C) with enlargement of the nerve and homogeneous enhancement is seen on T1 weighting without (C) and with (D)contrast. The patient presented with facial nerve palsy, sensorineural hearing loss, and tinnitus on the left. E–J: Patient 3. Facial schwannoma of the mastoid segment in the same patient as in Figure 130.1C–F. Larger tumors (arrow) compared to the normal facial nerve (arrowhead) may show inhomogeneous enhancement due to necrosis (E). Coronal T2 weighting also shows variable signal intensity (F). Images in (G) through (J) show a dumbbell appearance that is fairly typical of a schwannoma at least partially constrained by bony canal. On T2 weighting, the mass with inhomogeneous signal intensity is seen along the mastoid segment (arrow) and within the stylomastoid fat pad (arrowheads) on the left (G) compared to the normal nerve on the right (gray arrow). On contrast-enhanced T1 weighting, the mastoid segment tumor shows irregular (arrows) but not invasive margins (H, J), possibly due to the influence of surrounding bone. The extratemporal portion of the mass (arrow in I and arrowhead in J) shows sharply demarcated margins, likely because it is expanding into surrounding fat. Compare to the normal nerve and fat pad (gray arrows). The patient presented with facial nerve palsy. K–M: Patient 4. Schwannoma of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve extending along the greater superficial petrosal nerve. In (K) and (L), a lobulated (arrows) homogeneously enhancing mass extends into the middle cranial fossa and causes remodeling of the anterior aspect of the petrous apex. The lobulated pattern without dural reaction or vector is more typical of schwannoma than meningioma. In (M), the T2-weighted image shows morphology and signal intensity consistent (arrows) with a schwannoma, which was eventually proven surgically. (continued)

The spectrum and natural history of nerve sheath tumors is discussed in Chapter 29. Essentially, the nerve is slowly compressed as tumor cells grow within and around its coverings. The remaining facial nerve fibers will eventually become atrophic due to chronic compression or will cease to function because they have been replaced by tumor. It is possible that the tumor growth within the facial canal injures the nerve due to its mass effect, which produces a complicating ischemic neuropathy from the labyrinthine segment distally since the labyrinthine segment is the tightest part of the facial canal. By this process, a usually slow progressive facial nerve deficit might become transiently more rapidly progressive or sudden in onset.

The muscles of facial expression comprising the bulk of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) will go through the process of denervation atrophy. The muscles may enhance acutely and subacutely and then decrease in bulk and become fat replaced.

Manifestations and Findings

Computed Tomography

The CT and MR appearance of nerve sheath tumors is described in detail in Chapter 29.

CT may be normal if there is not underlying facial canal remodeling or erosion or if the causative pathology involves the segment of the nerve in the IAC. CT can potentially demonstrate structural pathology along the IAC nerve segment. It cannot exclude canalicular and sometimes cisternal segment involvement (Figs. 29.13 and 130.1).

MRI will usually be abnormal. It may only show minimal enlargement and increased enhancement of the affected facial nerve anywhere along its course (Figs. 29.1 and 130.2). MRI may also be normal, in which case CT should be done and/or the MRI repeated at a reasonable interval.

Both studies can be used to exclude structural lesions affecting the facial nerve more distally. Spread or origin of the tumor from the stylomastoid foramen distally within and especially beyond the parotid gland may be subtle if contrast is not given.

Differential Diagnosis

From Clinical Data

The patient will suffer a partial or complete peripheral (all of the muscles on one side of the face) facial nerve palsy. If acute and there are no other signs or symptoms, then this is likely a viral neuritis and can be properly referred to as a likely Bell palsy.

Bell palsy must never be confused with a peripheral facial nerve palsy of slow, progressive, or “stuttering” onset. If there are other signs of central nervous system disease (such as other cranial neuropathies), then the potential differential diagnosis is relatively large and includes demyelinating disease; Lyme disease; various causes of meningeal infection; and a variety of neoplastic conditions that might involve the temporal bone, skull base, facial nerve itself, meninges, and brain. Also, recurrent or persistent peripheral facial nerve palsy should never be considered a Bell palsy until it is proven not to be due to a structural lesion of the facial nerve. Conditions with these types of clinical characteristics atypicalfor Bell palsy will very often be the result of benign or malignant neoplasms or a handful of other causes that may occur anywhere along the nerve from its nucleus to its peripheral distribution, including a nerve sheath tumor.

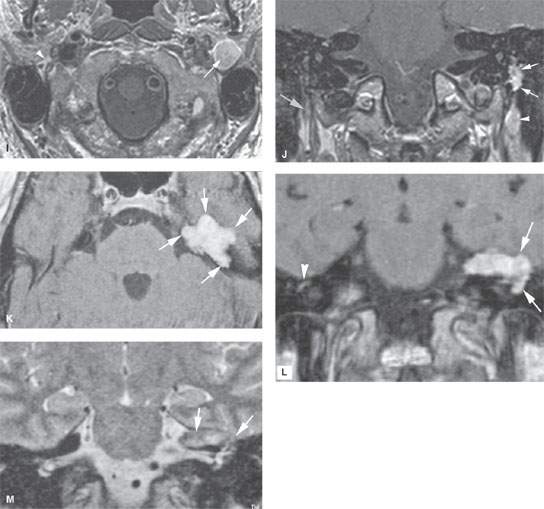

FIGURE 130.3. Patient presenting with slow-onset peripheral facial nerve palsy. A, B: Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showing a mass centered at the anterior genu with a density suggesting possible internal calcifications (arrows) and perhaps surrounding reactive bone. Meningioma and hemangioma were the primary working diagnoses. C, D: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images showing a lobulated mass without dural reactive changes (arrows) and a component entering the labyrinthine segment of the facial canal (refer to additional images in Fig. 124.4). E: T2-weighted image showing the dural–mass interface (arrow) and mixed signal intensity generally brighter than brain. (NOTE: While the features of the mass suggested a meningioma or hemangioma on CT, magnetic resonance imaging favored the correct diagnosis of a schwannoma.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree