Fair Game

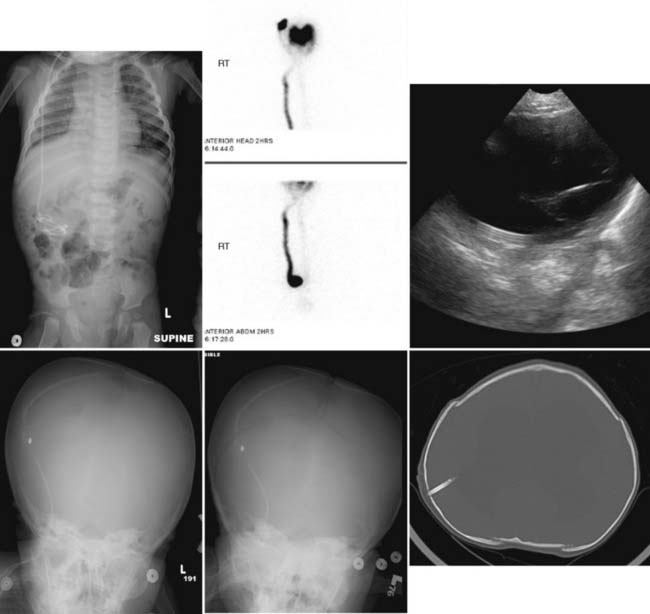

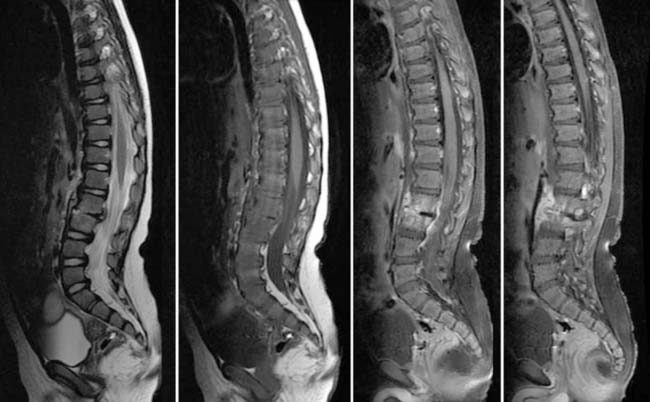

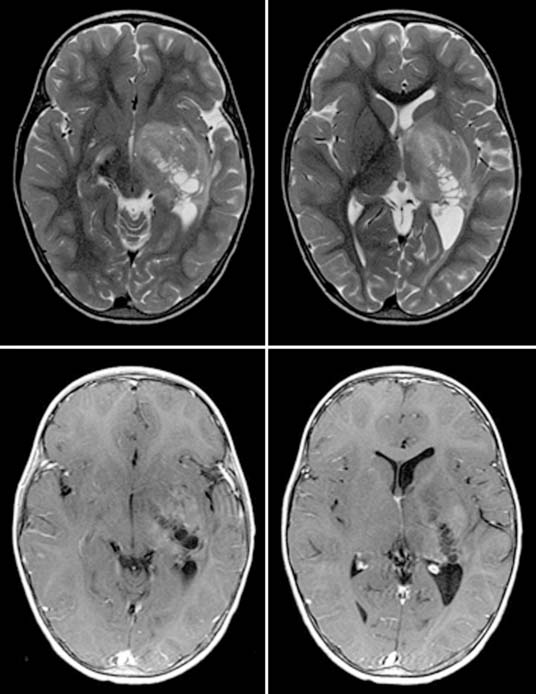

Case 49

Answers: Case 49

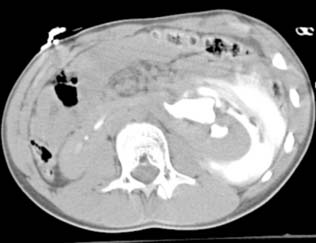

Diagnosis: Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Complications

Case 51

Case 52

Kayser R., Mahlfeld K., Greulich M., et al. Spondylodiscitis in childhood: results of a long-term study. Spine. 2005;30:318-323.

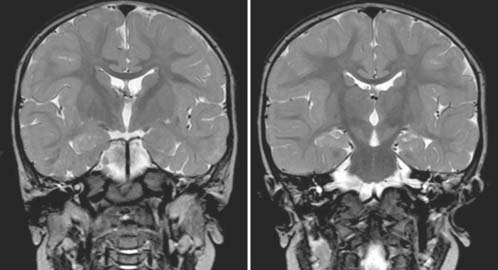

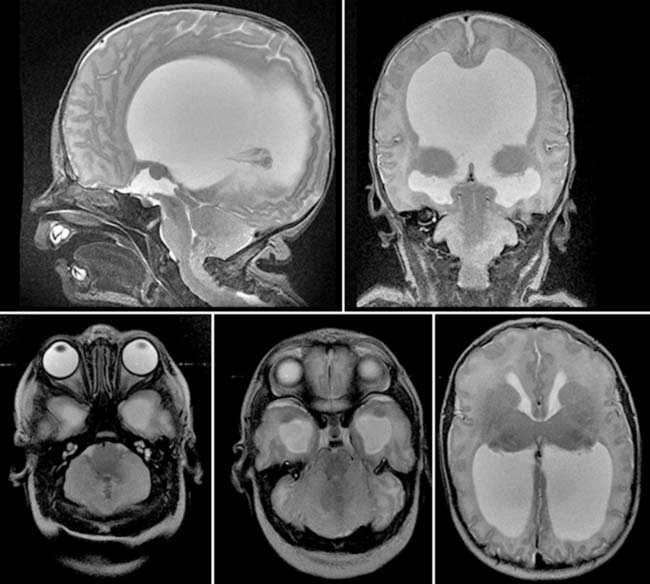

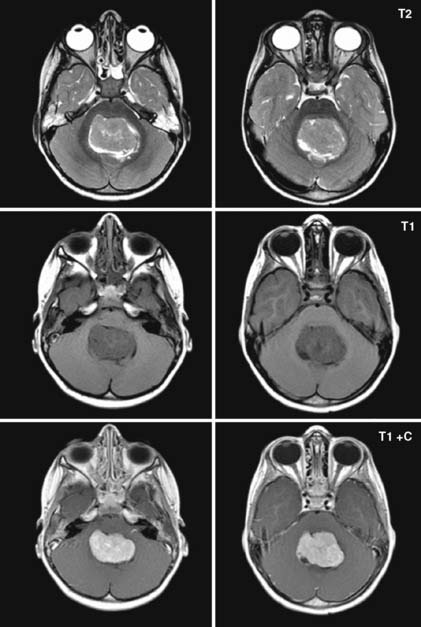

Case 53

Answers: Case 53

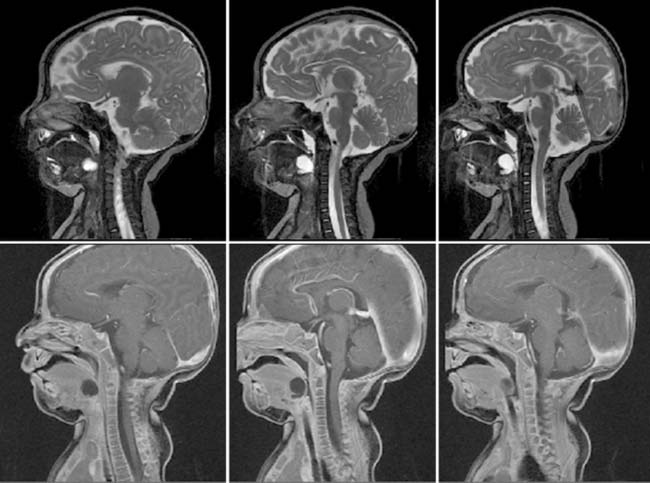

Diagnosis: Arnold-Chiari II Malformation

Barkovich A.J. Pediatric neuroradiology, diagnostic imaging. Salt Lake City: Amirsys Inc, 2007;III 16-III 19.

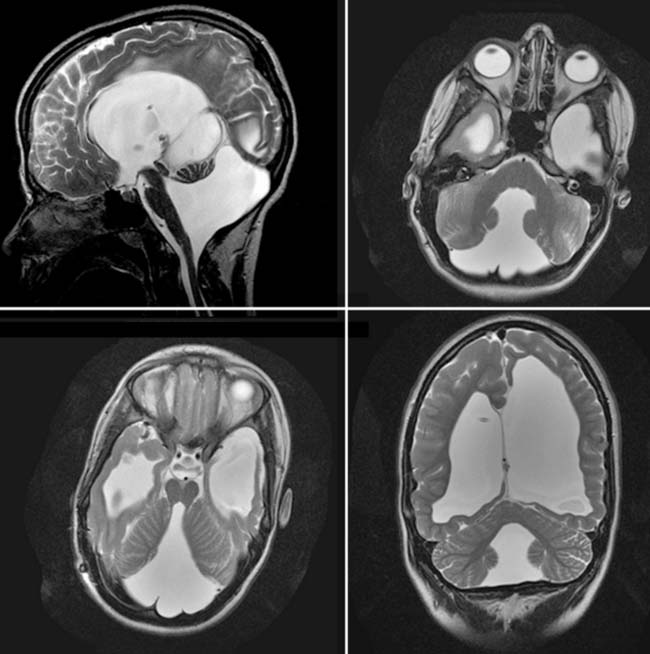

Case 54

Answers: Case 54

Patel S., Barkovich A.J. Analysis and classification of cerebellar malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1074-1087.

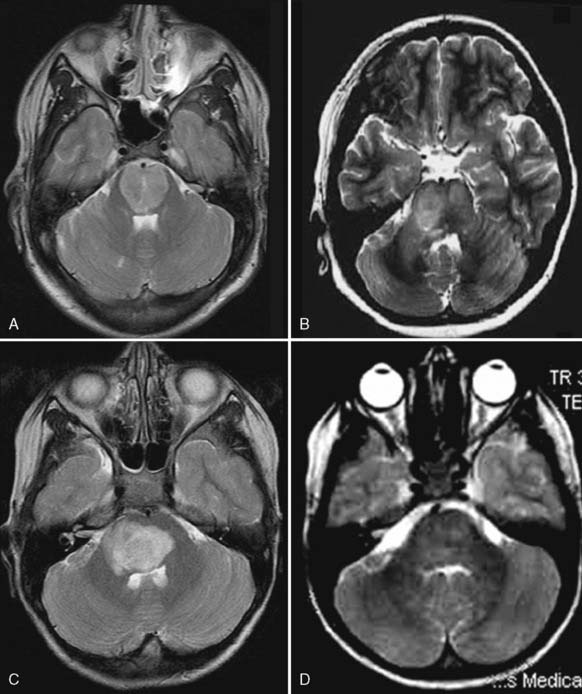

Case 55

Answers: Case 55

Case 56

Answers: Case 56

Case 57

Answers: Case 57

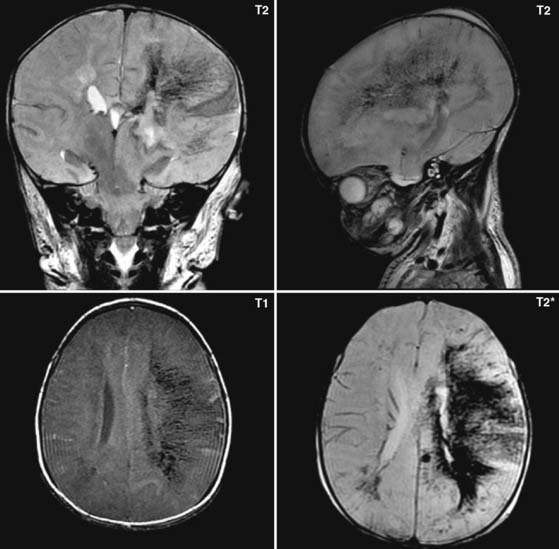

Case 58

Answers: Case 58

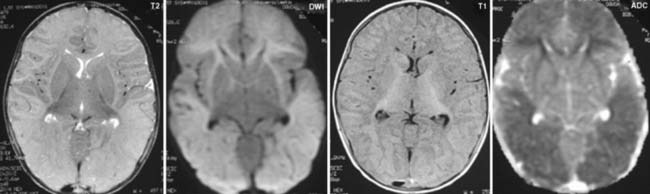

Diagnosis: Germinal Matrix Hemorrhage with Venous Infarction

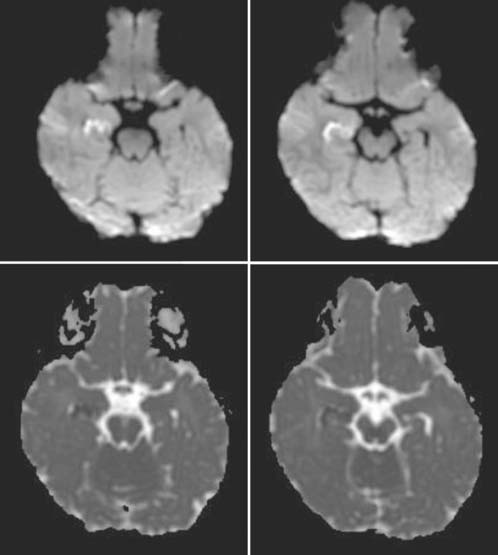

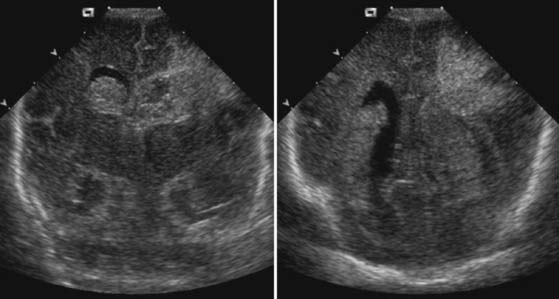

Case 59

Answers: Case 59

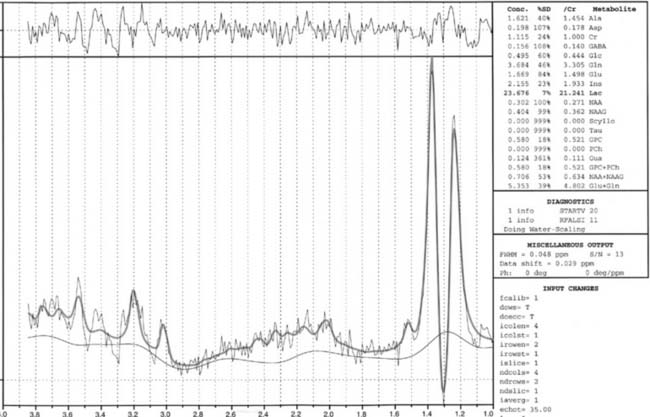

Diagnosis: Hypoxic-Ischemic Injury

Case 60

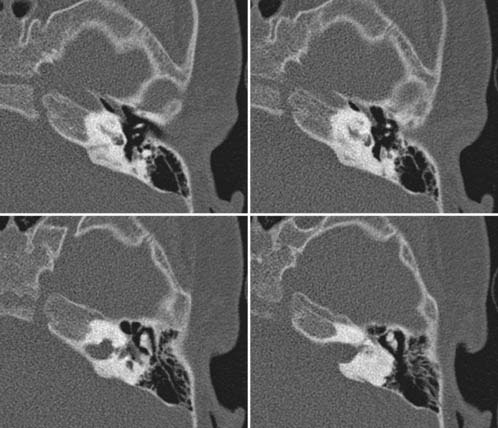

Answers: Case 60

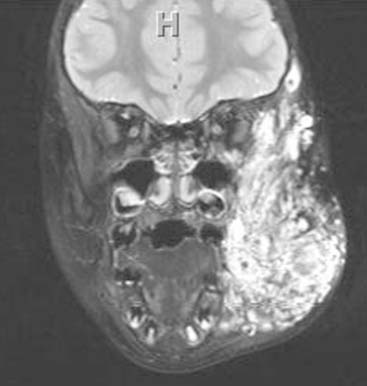

Diagnosis: Goldenhar Syndrome (Goldenhar-Gorlin Syndrome, Facioauriculovertebral Sequence)

Taybi H., Lachman R.S. Radiology of syndromes, metabolic disorders and skeletal dysplasias, ed 4, Baltimore: Mosby; 1996:356-358.

Case 61

Answers: Case 61

Diagnosis: Thyroglossal Duct Cyst

Moore K.M. The developing human, ed 2, Philadelphia: Saunders; 1977:160-180.

Barkovich AJ, Moore KR, Jones BV, et al, editors: Diagnostic imaging: neuroradiology, Salt Lake City, 2007, Amirsys, II 4:18-21.

Case 62

Answers: Case 62

Arndt C.A.S., Crist W.M. Common musculoskeletal tumor of childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:342-352.

Case 63

Answers: Case 63

Diagnosis: Subglottic Stenosis

Tekes A., Flax-Goldenberg R. Diagnostic imaging of the pediatric airway. Operative techniques in otolaryngology. Head Neck Surg. 2007;18(2):115-120.

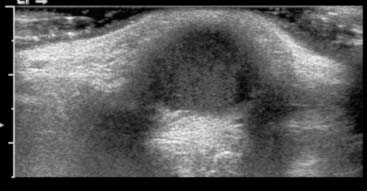

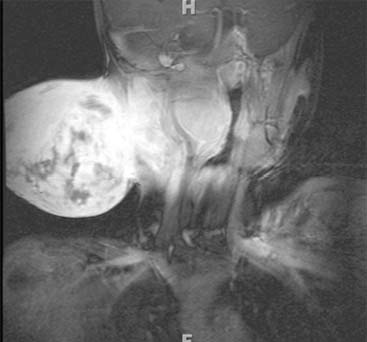

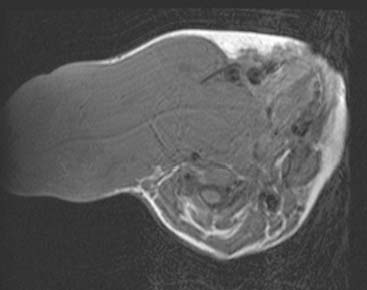

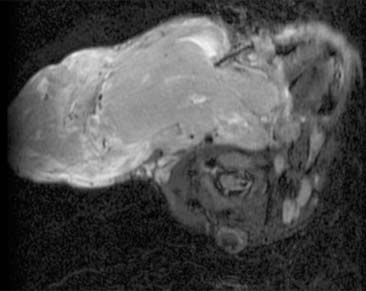

Case 64

Answers: Case 64

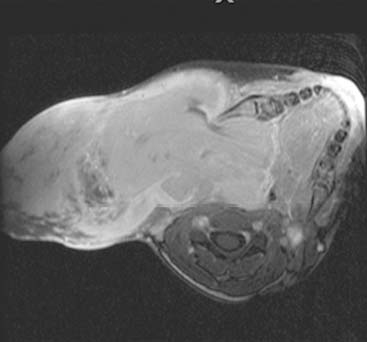

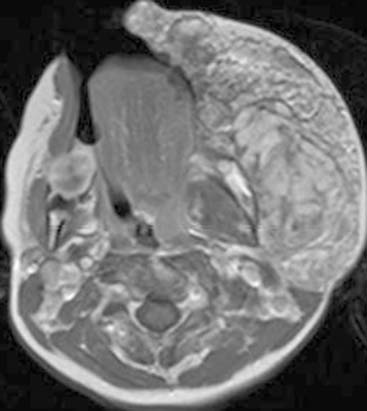

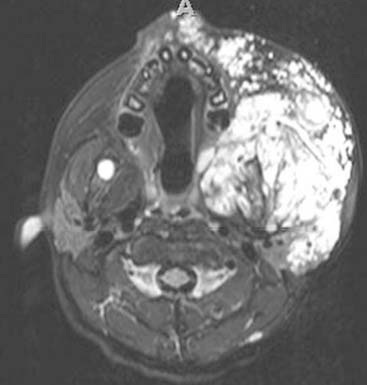

Diagnosis: Venous Malformation

Case 65

Answers: Case 65

Diagnosis: Paraspinal, Posterior Mediastinal Neuroblastoma

Kuhn J.P., Slovis T.L., Haller J.O. Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging, ed 10, Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004:1210-1215.