© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

Sabine Weckbach (ed.)Incidental Radiological FindingsMedical Radiology10.1007/174_2016_96Incidental Findings: Definition of the Concept

(1)

Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Münster, Germany

Abstract

In a broad sense, any findings can be called incidental that occur in the context of medical diagnostics and that potentially affect the health (including the reproductive capacities) of a living being – if the diagnostic means were not intended to produce such findings. It would be wrong to only talk about an incidental finding once the relevance for the health or reproductive capacity of the concerned individual has been established. The concept of an incidental finding rather includes – in its broad as well as narrow sense, which will be explained in the next paragraph – both marginal findings with no clinical relevance and false positive findings. This use of the concept makes sense, because the artefactual character of false positive findings in particular usually only becomes clear after further evaluation. Since this evaluation would not take place without the misleading primary finding, the concept of a finding cannot plausibly depend on the factual correctness or clinical relevance of diagnostic discoveries.

This chapter is derived from my handbook entry Schmücker (2013).

1 Incidental Findings in a Broad Sense

In a broad sense, any findings can be called incidental that occur in the context of medical diagnostics and that potentially affect the health (including the reproductive capacities) of a living being – if the diagnostic means were not intended to produce such findings. It would be wrong to only talk about an incidental finding once the relevance for the health or reproductive capacity of the concerned individual has been established. The concept of an incidental finding rather includes – in its broad as well as narrow sense, which will be explained in the next paragraph – both marginal findings with no clinical relevance and false positive findings. This use of the concept makes sense, because the artefactual character of false positive findings in particular usually only becomes clear after further evaluation. Since this evaluation would not take place without the misleading primary finding, the concept of a finding cannot plausibly depend on the factual correctness or clinical relevance of diagnostic discoveries.

Incidental findings understood in this sense can occur in the context of research in life sciences or while diagnostic means are employed to confirm the presence of a certain disease. They can also occur when magnetic resonance images are taken for an anatomical atlas or when a follow-up examination for a cured disease shows indications of a different disease.

Diagnostic findings that occur in the context of the doctor-patient relationship while searching for the cause of certain symptoms, but that do not comply with the doctor’s expectations concerning this cause, are not incidental findings – not even according to the broad concept of incidental findings. The examination is aimed at establishing findings that would explain the reported symptoms, even if those findings do not comply with the physician’s expectations. Diagnostic findings that occur in the context of direct–to–consumer genetic analyses or direct–to–consumer whole-body MRI examinations that are offered by commercial companies as individual check-ups also do not count as incidental findings. For there is, although no treatment contract is involved here, a contractual relationship between the subject of the preventive examination and the provider of the latter that resembles the relationship between doctor and patient in at least one respect, due to the preventive aim it is based on: the purpose of the contract and the examination is to collect information relevant for the subject’s health. This information can help the subject make an informed decision about measures that will serve sustain her health for as long as possible. Even in the broad sense of the concept, it is not an instance of incidental findings if (a) a diagnosis is carried out, because the examined person demanded it – even without presenting any symptoms – in order to find out about a potential need for medical intervention or (b) a cause of the patient’s symptoms is found that differs from what is expected by the physician who is responsible for the diagnosis. In the latter case, the findings differ from what is expected or considered likely by the physician. So the findings are unexpected, but not incidental. It is not the case that the use of the diagnostic means did not intend to produce the findings. This becomes clear once we consider the intention of the physician when employing diagnostic means. The physician does not primarily examine the patient with the aim of finding the cause of a symptom or confirming the presence of a certain disease. She rather wants to find out which therapeutic measures should be undertaken for the patient’s benefit. The physician’s intention is not primarily to confirm her own suspicion concerning the cause of the symptoms. The aim is usually rather to cure the patient as soon as possible. This can also be seen in the fact that an experienced physician will abstain from any further diagnostic procedures if she is confident that further differential diagnostics will be irrelevant for the indication of adequate therapeutic measures. In this case, any further examination would be unnecessary for the treatment of the patient and would only be carried out for the sake of confirming the physician’s hypothesis. Since the latter is not the aim of the physician’s conduct, no further examinations are required.

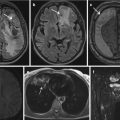

The occurrence of an incidental finding can nowadays not be regarded as unexpected. It has become evident – and is a matter of basic knowledge in modern research – that the use of high-resolution imaging diagnoses in medical studies yields a relatively high number of findings that the study was not aimed at detecting (Rangel 2010, 124). In brain MRI scans, 1–8% of subjects featured incidental findings that were considered in need of further examination (Katzman et al. 1999; Alphs et al. 2006; Weber and Knopf 2006; Vernooij et al. 2007; Schleim et al. 2007; Gupta and Belay 2008). In cohort studies employing whole-body MRI, the number of incidental findings is even higher (Langanke and Erdmann 2011, 206). Unexpected findings neither are always incidental nor are incidentally discovered findings always unexpected. Therefore it would be inadequate to characterize incidental findings as unexpected findings (pace, e.g. Illes et al. 2006, 783; Heinemann et al. 2007, A1982). Incidental findings should rather be characterized as unintended findings whose discovery was not intended by a treating physician or medical researcher. Their discovery was not intended, because the intention of a treating physician is not – in contrast to, e.g. the provider of direct-to-consumer whole-body MRI examinations – to discover a clinically not (yet) manifested disease, and the intention of the researcher in life sciences is not to provide a diagnosis for the subject’s disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree