Chapter 5 Fingers, hand and wrist

Thumb

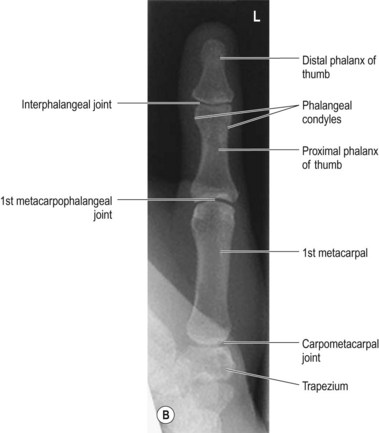

Anteroposterior (AP) thumb

Traditionally the AP thumb projection has been described with the patient seated,1 but these positions create difficulties when trying to clear the hypothenar eminence from the field. Method 1 described here uses a position considered to be significantly more comfortable and achievable than others and may be at variance with the most commonly performed methods (methods 2 and 3). The idea for method 1 was originally researched with the patient in an erect position,2 with the later suggestion that radiation protection and immobilisation might be more effective if the patient is supine.3

For all projections of the thumb the IR is placed horizontal unless otherwise specified.

Positioning

Method 1: Patient supine (Fig. 5.1A,B)

• The patient is supine with the affected arm flexed at the elbow and the dorsum of the hand initially in contact with the IR. Lead rubber is applied to the trunk

• The fingers are extended and separated from the thumb

• The anterior aspect of the thumb is placed in contact with the IR and adjusted until the long axis of the thumb is parallel to it; the hypothenar eminence is cleared from the thumb and thenar eminence

• As the dorsum of the hand is now not in contact with the IR, a radiolucent pad is used under the dorsum to aid immobilisation

Method 2: Patient seated alongside table (Fig. 5.2)

• The patient is seated with the affected side next to the table; lead rubber is applied to the waist

• The affected hand is externally rotated and the thumb cleared from the fingers

• The anterior aspect of the thumb is placed in contact with the IR; it may be necessary for the patient to lean towards the table in order to facilitate this

• A radiolucent pad is used under the dorsum of the hand to aid immobilisation

• Care must be taken to clear the hypothenar eminence from the first metacarpal

Method 3: Patient seated with back to table (Fig. 5.3)

• The patient is seated with their back to the table, with a lead rubber apron fastened behind the waist

• The affected arm is abducted posteriorly and medially rotated

• The anterior aspect of the thumb is placed in contact with the IR; the hypothenar eminence is cleared from the thumb and thenar eminence

• A radiolucent pad is used under the dorsum of the hand to aid immobilisation

• Care must be taken to clear the hypothenar eminence from the first metacarpal

Popular opinion would suggest that the creation of an air gap between the thumb and the IR also requires an increase in mAs, in order to effect further film blackening as compensation for the reduction in scatter. For denser body areas requiring higher exposure factors than the thumb, this would be a relevant consideration. However, as this projection is performed with the selection of a relatively low kVp, the dominant interaction process is one of absorption rather than production of scatter. Therefore this negates the requirement for an increase in mAs (see Ch. 3). Possible other disadvantages of using the PA projection are the possibility of poor maintenance of position and immobilisation; use of immobilisation aids therefore becomes of paramount importance.

PA thumb (Fig. 5.4)

Positioning

• The patient is seated with the affected side next to the table; lead rubber is applied to the waist

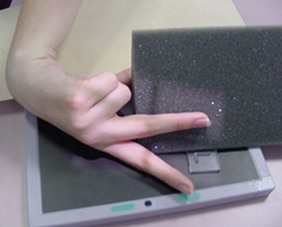

• From a dorsipalmar (DP) position, the hand is externally rotated through 90° and the lateral border of the wrist placed in contact with the table

• The fingers are extended and superimposed vertically; the thumb is extended and cleared away from the fingers

• The long axis of the thumb is supported in a horizontal position by a radiolucent pad

• The thumb and thenar eminence are cleared from the hypothenar eminence and palm of the hand

Criteria for assessing image quality (all AP methods and PA method)

• All phalanges, first metacarpal, trapezium and soft tissue outline are demonstrated and clear of the hypothenar eminence

• Clear interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joint spaces; symmetry of the phalangeal condyles

• Sharp image demonstrating soft tissue margins of the thumb and thenar eminence, bony cortex and trabeculae; adequate penetration of thenar eminence to demonstrate first metacarpal and trapezium

| Common errors | Possible reasons |

|---|---|

| Interphalangeal joint space not clearly demonstrated | Long axis of thumb may not be parallel to IR |

| Asymmetry of phalangeal condyles | Transverse axis of thumb may not be parallel to IR |

| AP methods 1–3 | |

| Shadow of hypothenar eminence superimposed over first metacarpal and trapezium | Inadequate rotation of hand; rotate hand further to clear |

| PA | |

| Shadow of thenar and hypothenar eminence superimposed over first metacarpal and trapezium | Thumb may be positioned too close to the rest of hand; clear thumb and first metacarpal from hand and fingers |

Lateral thumb (Fig. 5.5A–C)

Positioning

• The patient is seated with the affected side next to the table; lead rubber is applied to the waist

• In the DP position the thumb is cleared from the fingers and the hand is medially rotated until the thumb lies laterally, with its phalangeal condyles superimposed

• Because the medial aspect of the hand will be raised to achieve the correct position, a radiolucent pad is used under the palmar aspect of the hand to aid immobilisation

• An alternative method for immobilisation is to flex the fingers into the palm while maintaining separation of the thumb from the rest of the hand, and use the fist to support the dorsum in the required position (Fig. 5.5B)

Criteria for assessing image quality

• All phalanges, first metacarpal, trapezium and soft tissue outlines are demonstrated

• The thumb, first metacarpal and trapezium are cleared from the fingers and hand

• Superimposition of phalangeal condyles to clear interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joint spaces

• Sharp image demonstrating the soft tissue margins of the thumb and thenar eminence, bony cortex and trabeculae. The thenar eminence should be penetrated to adequately demonstrate first metacarpal and trapezium

| Common error | Possible reason |

|---|---|

| Poor joint space visualisation and non-superimposition of phalangeal condyles | Hand has not been rotated adequately; medial or external rotation of the hand will facilitate superimposition of phalangeal condyles |

Fingers

One way to ensure this is to include the adjacent finger or border of the hand in the field of collimation; comparison of size with the other fingers will ensure correct identification of the finger. Unfortunately this does involve irradiation of areas not required for examination and could theoretically be deemed to be in contravention of IR(ME)R 2006.4 As a result, imaging department protocols should clearly identify the hospital’s requirements for the radiographer, ensuring that there is uniformity of provision regarding finger images.

DP fingers (Fig. 5.6A,B)

For all projections of the fingers the IR is horizontal.

Criteria for assessing image quality

• Centring method (a): All phalanges and the metacarpophalangeal joint are demonstrated

• Centring method (b): All phalanges, the metacarpophalangeal joint and the metacarpal are demonstrated

• Adjacent finger/s and soft tissue outline of the affected and adjacent fingers are demonstrated

• Symmetry of the phalangeal condyles

• The interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joint spaces are clearly visible and open

• Sharp image demonstrating the soft tissue margins of the finger, bony cortex and trabeculae

| Common error | Possible reason |

|---|---|

| Interphalangeal joint spaces not clearly demonstrated | Fingers may be flexed; extend to clear |

Lateral fingers

Positioning

Index (first) finger (Fig. 5.7A,B)

• From the DP position the hand is internally rotated through 90° and the third and fourth fingers are flexed and held in position by the thumb

• The index finger is extended and positioned with its lateral aspect in contact with the IR

• The long axis of the index finger is separated from the palmar-flexed middle finger with a radiolucent pad

Middle finger (Fig. 5.8)

• From the DP position, the hand is internally rotated 90° and positioned as for the lateral index finger projection

• The middle finger is extended and separated from the index finger with a radiolucent pad

• The middle finger is supported in a horizontal position by a radiolucent pad

Ring and little finger: method 1 (Fig. 5.9)

• From the DP position the hand is externally rotated through 90°

• The index and middle fingers are flexed and held by the thumb; the little finger remains extended, as does the ring finger

• The medial aspect of the fifth metacarpal is in contact with the IR

• The ring finger is slightly dorsiflexed to clear it from the little finger

• If under examination, the ring finger is supported in a horizontal position; in any event it is separated from the little finger by a radiolucent pad

Ring and little finger: method 2 (Fig. 5.10)

• From the DP position the hand is externally rotated through 90°

• The index finger is flexed and held by the thumb; the remaining fingers are slightly dorsiflexed and fanned out; their long axes remain horizontal

• If under examination, the ring finger is supported in a horizontal position; in any event it is separated from the other fingers by radiolucent pads

For all the fingers and positions

Collimation

Centring method (a): All phalanges, soft tissue outlines and the metacarpophalangeal joint. Evidence of the adjacent finger for confirmation of identification of the finger under examination

Centring method (b): All phalanges, soft tissue outlines and the associated metacarpal. Evidence of the adjacent finger for confirmation of identification of the finger under examination

Criteria for assessing image quality

• Centring method (a): All phalanges and the metacarpophalangeal joint are demonstrated, with the outline of adjacent finger/s

• Centring method (b): All phalanges, the metacarpophalangeal joint and the metacarpal are demonstrated with the outline of adjacent finger/s

• Clear interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints are demonstrated, with phalangeal condyles superimposed

• Sharp image demonstrating the soft tissue margins of the finger, bony cortex and trabeculae of phalanges under examination

| Common error | Possible reason |

|---|---|

| Poor joint space demonstration with non-superimposition of phalangeal condyles | Long axis of finger may not lie parallel to IR; reposition and support more effectively or angle beam to coincide with angle of interphalangeal joints if patient cannot comply |

Hand

DP hand (Fig. 5.11A,B)

For all projections of the hand the IR is placed on the table-top.

Criteria for assessing image quality

• All phalanges, the wrist joint and the soft tissue outline of the hand are demonstrated

• The fingers are separated, and the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints are clear

• Symmetrical appearance of the heads of metacarpals 2–4

• Obliquity of thumb and the heads of metacarpals 1 and 5

• Sharp image demonstrating the soft tissue margins of the hand, bony cortex and trabeculae Adequate penetration to demonstrate the hook of hamate whilst showing distal phalanges

| Common errors | Possible reasons |

|---|---|

| Superimposition of soft tissue outlines of fingers | Fingers are not separated adequately |

| Poor demonstration of joint spaces |