, Yves Etienne2 and Maurice Niddam3

(1)

Faculté de Médecine, Marseille, France

(2)

Unité de Médecine Légale, Hôpital de la Timone, Marseille, France

(3)

Unité SAMU 13, Centre 15, Hôpital de la Timone, Marseille, France

The first psychosurgery attempts date back to 1891. The alienist, Dr Gottlieb Burckhardt,1 performed a cortical resection using a curette on either side of the central sulcus of the brain in six patients presenting severe agitation. In one of the patients, agitation was significantly attenuated, but another died and the last one became epileptic. These results provoked strong emotions in the local medical community, forcing Burckhardt to stop his surgeries.

It was not until 1935 that psychosurgery truly entered an active phase. In this period between two wars, E. Moniz,2 a Portuguese neurologist, performed the first prefrontal lobotomy in restless and anxious subjects. Moniz, whose jurisdiction was unanimously recognised (he developed the cerebral angiography) and who also benefited from political influence (he was a foreign minister), disseminated psychosurgery widely, which had a particularly significant impact in the USA, especially in Stanford University with WJ Freeman3 who performed 3,500 lobotomies!

The psychological sequelae presented by soldiers returning from World War II represented a land of choice for these prefrontal lobotomies. In 1943, the “Veteran’s Administration” also encouraged neurosurgeons to acquire additional training in this area.

Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1949 for his efforts and his achievements in psychosurgery. It should be noted that at that time, neuroleptics were unknown; they were introduced in psychiatry by J. Delay and P. Deniker only from 1952. These “chemical straitjackets” transformed psychiatry and the image of the hospitals involved. The prefrontal lobotomy (illustrated in 1975 by Milos Forman’s film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” starring Jack Nicholson) gradually fell into disuse as the use of neuroleptics increased. Admittedly, surgical results were more beneficial to the patient’s entourage than to the patient. Indeed, these patients’ aggressive behaviour after prolonged military conflicts or their psychologically trauma caused by the emotions of combat represented an ongoing risk to those around them and to society.

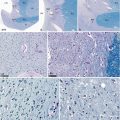

Advances in behavioural neurobiology revived surgical techniques. In 1937, the work of H. Klüver and PC Bucy (see History chapter) on the limbic lobe of the monkey, and more specifically the amygdala, revealed this structure as the regulatory centre of emotions. WH Mark and F Erwin (1970) emitted the idea that violence was the expression of a deficient inhibitory control of aggression called “dyscontrol syndrome” that only the removal of the amygdala could cure.

In this period, new contemporary armed conflicts (Vietnam War from 1965 to 1975), a Japanese surgeon, H Narabayashi (1972), treated hyperkinetic children with localised destruction of the amygdala. Surgical results were satisfactory for aggressiveness but altered considerably the affectivity of operated patients. Again, it must be emphasised that the surgical indication by the admission of Narabayashi was primarily driven by the entourage, perhaps with a view towards academic achievement and upward mobility. The Japanese surgeon confided that it was mostly the father who prompted the consultation and was satisfied with the result (the child becoming more obedient), while the mother reconsulted him privately to ask if he could return her child to the same state as before the surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree