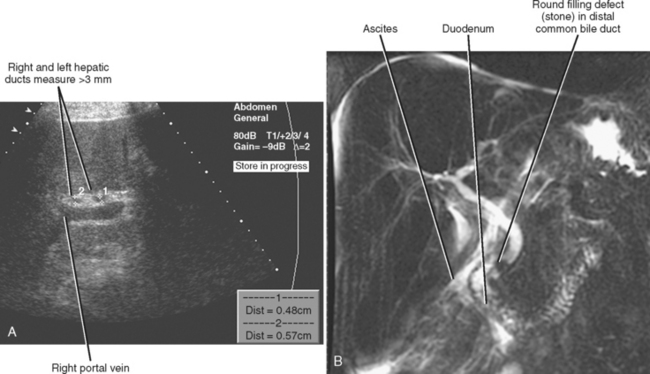

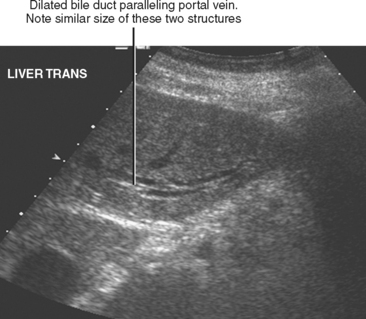

Figure 13-28 Ultrasound images through the left hepatic lobe of a patient with obstructing choledocholithiasis.

CHAPTER 13 Gallbladder and Bile Ducts

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Cholangitis

Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (RPC) is characterized by recurrent bouts of cholangitis associated with intrahepatic stones and biliary strictures. This disorder is predominantly found in Asia (and was previously called oriental cholangiohepatitis), although Asian immigrants elsewhere in the world can present with RPC. Symptoms include right upper quadrant pain, fever, and mild jaundice. Leukocytosis and a cholestatic pattern of liver function tests are often present. If left unchecked, cirrhosis or liver failure may ensue. Additional complications of RPC include choledochoduodenal fistula, stone-related pancreatitis, and cholangiocarcinoma.

ANATOMY OF THE BILIARY SYSTEM

Variant Biliary Anatomy

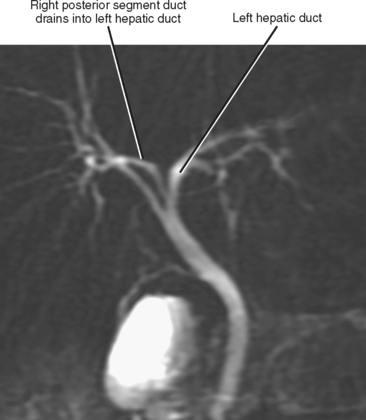

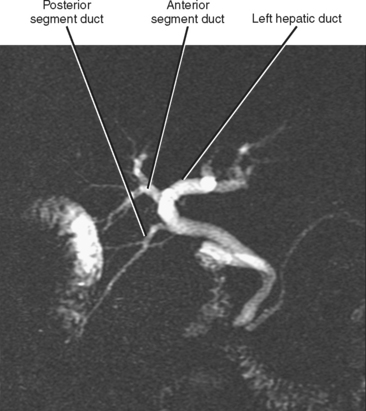

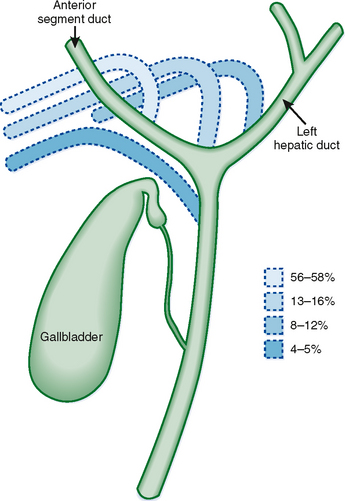

Variations in biliary anatomy are common; less than two thirds of individuals exhibit standard bile duct anatomy (one of the authors has a right posterior segment duct draining into his left hepatic duct). The most common biliary anatomic variants involve aberrant confluence of the right posterior segment duct (Figs. 13-1 to 13-3). Variations in bile duct anatomy do not necessarily parallel variations in portal venous anatomy. Variations of the cystic duct include a long parallel course with low insertion into the common duct, insertion into the left side of the common duct, and drainage into a right hepatic duct. Rarely, an accessory hepatic duct may enter the gallbladder. Agenesis, duplication, and ectopic location of the gallbladder may also rarely occur.

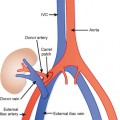

Figure 13-1 Common variations of the biliary confluence that involve the right posterior segment duct.

Gallbladder Anatomy

Several anatomic structures are in close proximity to the gallbladder. The gallbladder neck is intimately associated with the lateral proximal duodenum, and the gallbladder fundus resides near the hepatic flexure of the colon. The body and fundus of the gallbladder are also immediately adjacent to segments IVb and V of the liver. Veins drain directly into adjacent liver from the body and fundus of the gallbladder.

NORMAL IMAGING APPEARANCE OF THE BILIARY SYSTEM

The normal intrahepatic bile ducts course along with the portal veins and appear as thin structures that may be visible on either side of the accompanying vein on imaging studies. The right and left hepatic ducts are usually less than 3 mm in diameter. With improvements in imaging techniques, intrahepatic ducts are routinely visible with a variety of imaging modalities. The common bile duct usually measures less than 6 mm in diameter, although larger ducts are occasionally visible in patients without bile duct obstruction. There is significant variability in the literature regarding the location from which extrahepatic bile-duct measurements are taken. With ultrasound (US), the bile duct is typically measured at the level of the right hepatic artery, although the maximum duct diameter may be a more useful measurement. Advanced age has been associated in some studies with increased common duct diameter, although most elderly patients have a common bile duct diameter less than 6 mm. Likewise, several studies have linked prior cholecystectomy with increased bile duct diameter, although several other studies have failed to confirm a clinically relevant effect of cholecystectomy on common bile duct diameter. When the common bile duct is dilated from choledocholithiasis, the bile duct will return to normal in three fourths of patients after choledochostomy.

GALLSTONES AND SLUDGE

Gallstones

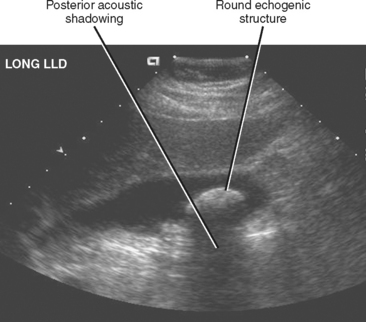

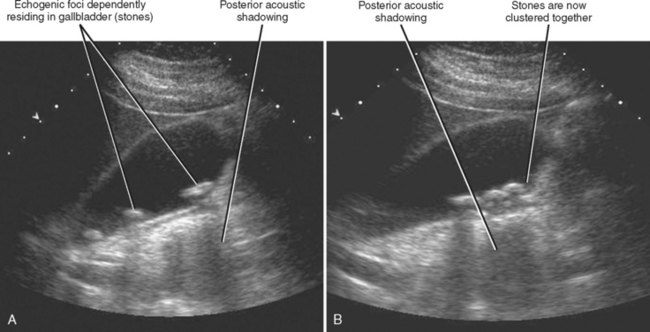

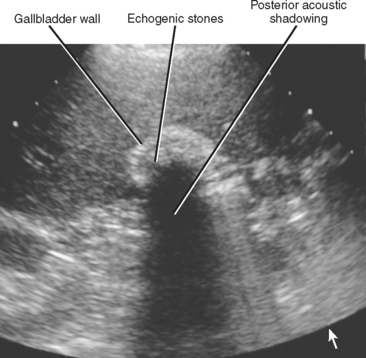

Transabdominal US is highly sensitive for the diagnosis of uncomplicated cholelithiasis. Larger (>5 mm) stones appear as echogenic foci with strong posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 13-4). The color comet tail artifact (“twinkle artifact”) can be helpful for confirming the presence of a stone, and the intensity of this artifact is related to the surface characteristics of the stone. Isolated stones smaller than 5 mm may not demonstrate acoustic shadowing but can be differentiated from polyps by their mobility. In general, when echogenic foci are detected with sonography, one should image in several different patient positions to confirm mobility of the abnormality (Fig. 13-5). Large stones or collections of smaller stones may completely fill the gallbladder, making the gallbladder difficult to identify. The WES (wall-echo-shadow) complex has been described as a means of differentiating gallstones filling the gallbladder from other abnormalities such as emphysematous cholecystitis or porcelain gallbladder, or structures such as the colon (Fig. 13-6). Before invoking the WES complex, one must ensure that the wall is seen as a distinct entity. When air or calcium is present in the gallbladder wall, a normal wall is not visualized. Instead, only an echogenic line and posterior shadow are seen. Stones impacted within the neck or cystic duct of the gallbladder may not be outlined by anechoic bile and can be missed. Therefore, it is always important to examine the neck region and cystic duct to detect evidence of posterior acoustic shadowing and color comet tail artifact. Cystic duct stones, in particular, are a relatively frequent cause of false-negative US results for cholelithiasis.

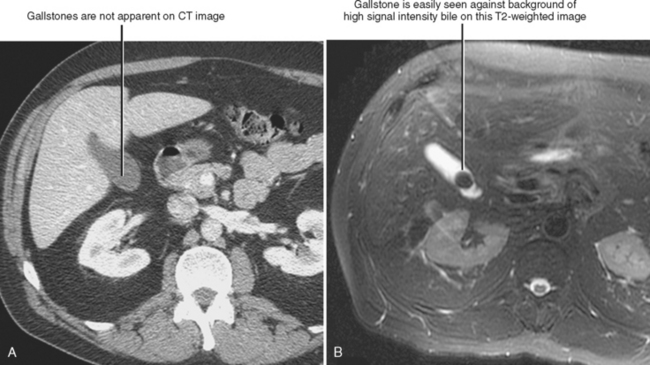

CT is considerably less sensitive than US but more sensitive than radiographs for detection of gallstones. CT is primarily used in patients with abdominal pain when acute cholecystitis is not the prime consideration and should not be relied on to exclude the presence of gallstones. On CT, gallstones range from hypodense (pure cholesterol stones) to hyperdense and may occasionally contain gas. It is not unusual for even large stones to be missed on technically excellent CT images (Fig. 13-7).

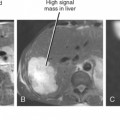

Although MRI is rarely performed as the primary means of diagnosing cholelithiasis, MRI is highly sensitive for the detection of gallstones, particularly when motion-insensitive T2-weighted images are performed. Gallstones are typically very low signal intensity on T2-weighted images and variable (very dark to very bright) signal intensity on T1-weighted images.

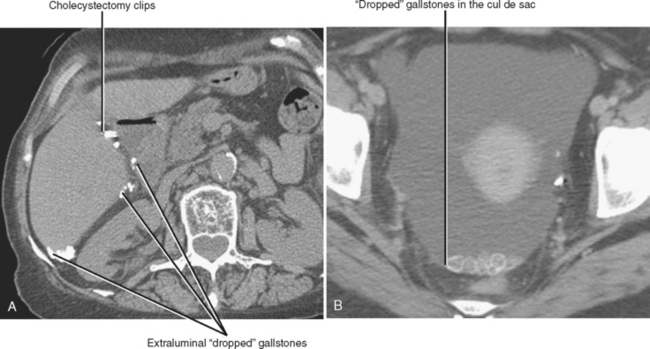

Occasionally, dropped gallstones will be encountered on imaging examinations after cholecystectomy (usually laparoscopic cholecystectomy). These most often accumulate in the subhepatic space but may be found as far away as the pelvis (Fig. 13-8). The most frequent complication of dropped gallstones is abscess formation. Abscesses related to dropped gallstones can present months to years after cholecystectomy.

Other Substances That Fill the Gallbladder

Biliary Sludge

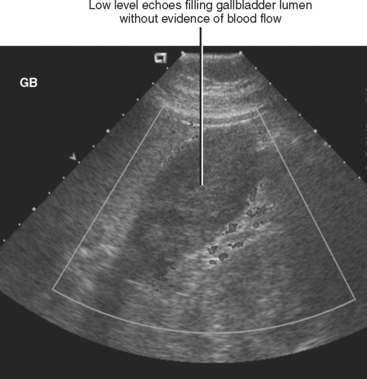

Sludge consists of precipitated material within the bile that cannot be resolved into individual particles on imaging studies. With sonography, sludge appears as dependent, low-level echoes within the gallbladder lumen (Fig. 13-9). Sludge is usually amorphous, lacks internal vascularity, does not shadow, and slowly changes shape and position with patient movement. When sludge fills the entire gallbladder lumen, it produces echogenicity similar to liver. This observation led the expression “hepatization of the gallbladder.” Occasionally, sludge can take on a rounded, masslike appearance mimicking a gallbladder polyp or cancer (tumefactive sludge). Tumefactive sludge will change appearance between serial US examinations. About half of patients with gallbladder sludge will experience spontaneous resolution, whereas at most 15% of patients will progress to cholelithiasis.

THICK-WALLED GALLBLADDER

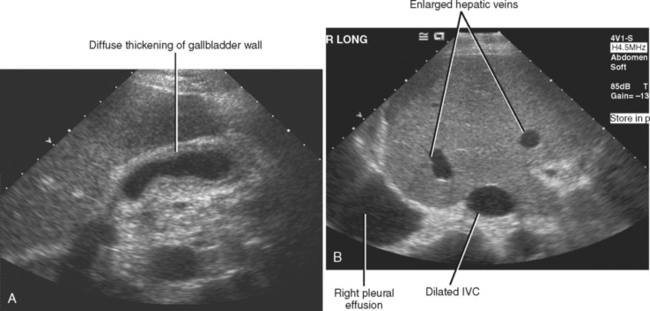

Diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall is one of the most common abnormalities seen on an US examination of the right upper quadrant. This is due to the myriad of processes that result in gallbladder wall thickening. Many of the causes of gallbladder wall thickening are listed in Table 13-1.

Table 13-1 Causes of Gallbladder Wall Thickening

| Cause | Diagnostic Clues (Variably Present) |

|---|---|

| Adenomyomatosis (Fig. 13-11) | |

| Adjacent inflammation | |

| Carcinoma (Fig. 13-12) | |

| Cholangiopathy/cholangitis (e.g., acquired immune deficiency syndrome cholangiopathy, sclerosing cholangitis) | |

| Cholecystitis (Fig. 13-13) | |

| Cirrhosis | |

| Congestive heart failure (Fig. 13-14) | |

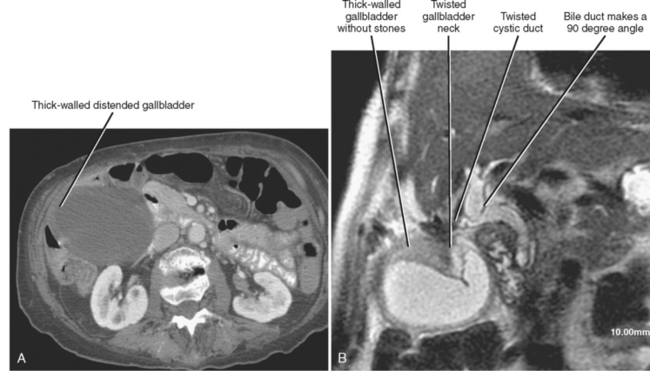

| Gallbladder torsion (Fig. 13-15) | |

| Hepatitis (Fig. 13-16) | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | |

| Nondistention | |

| Varices (Fig. 13-17) |

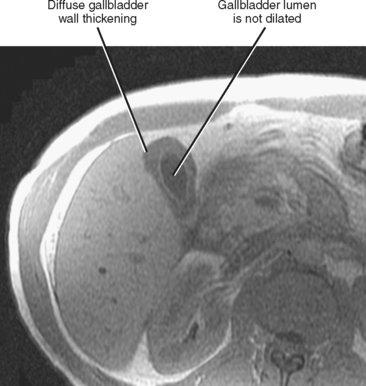

Figure 13-16 Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image through the gallbladder of an asymptomatic patient with acute hepatitis C.