and Gustavo Marino2

(1)

Attending Physician VA Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

(2)

Chief Gastroenterology Section VA Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

5.2.1 Gallbladder

5.2.1.1 Cholecystitis and Cholelithiasis

5.2.1.2 Gallbladder Carcinoma

5.2.1.3 Gallbladder Cysts

5.2.1.4 Courvoisier’s Sign

5.2.1.5 Heister Valves

5.2.2 Liver

5.2.2.1 A Growing Subhepatic Cyst

5.2.2.2 Hemangioma

5.2.2.3 Hepatoma

5.2.2.4 Hepatic Lymph Nodes

5.2.3 Bile Ducts

5.2.3.3 Common Bile Duct Stone

5.2.3.5 Possible “Narcotic Bile Duct”

5.2.3.6 Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

5.2.3.7 Malignant Bile Duct Stricture

5.2.3.11 Choledochocele vs. Bile Duct Web

Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is one of the best modalities for imaging the gallbladder and bile ducts. Substantial portions of the liver can also be examined by EUS as the instrument is advanced through the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, as the following image shows.

5.1 General Principles

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is one of the best modalities for imaging the gallbladder and bile ducts. Substantial portions of the liver can also be examined by EUS as the instrument is advanced through the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum.

The number of differential diagnostic possibilities for abnormalities of the gallbladder and bile ducts is limited. In contrast, there are many liver lesions that have a similar appearance on ultrasound but different clinical implications. Fortunately, it is not too difficult to acquire a working knowledge of liver diagnostic ultrasound by using online resources such as the World Health Organization’s Manual of Diagnostic Ultrasound [1] (see Box 5.1). Careful scrutiny of the liver needs to be a routine part of any staging of tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

While the gallbladder can easily be found in the upper gastrointestinal tract from the antrum and duodenum during an EUS exam, a cursory exam is not recommended. Small stones can easily be missed unless the gallbladder is evaluated in a protocol-driven fashion. As previously stated, endosonographers need to be familiar with the basics of conventional abdominal ultrasound anatomy. The thickness of the normal gallbladder wall measured by ultrasound has been found to be 2.1 ± 0.06 mm [2]. A value greater than 3 mm is considered abnormal. It is important to keep in mind that cirrhosis or hepatitis without intrinsic gallbladder pathology can increase this thickness.

A quick review of the basics can be accomplished by watching the videos listed in Box 5.1. The most common gallbladder finding are stones and polyps, which, when less than 10 mm in size, are almost never malignant. An excellent tutorial about the portal venous anatomy was published in the new open access journal Endoscopic Ultrasound (see Box 5.1), and we will describe some cases illustrating portal vein pathology.

EUS is particularly strong in the evaluation of the extrahepatic bile duct and, as the cases in this chapter illustrate, is often instrumental in establishing a diagnosis or change in the management plan.

Box 5.1: Free Online Resources

Manual of Diagnostic Ultrasound (World Health Organization, 2011) http://is.gd/ioA6rH

Three-part instructional video about gallbladder ultrasound provided by Sonosite (www.sonosite.com)

Part 1 http://is.gd/60NQXD

Part 2 http://is.gd/83oiJH

Part 3 http://is.gd/E5clEx

A seven-part instructional video about liver ultrasound provided by SonoWorld (www.sonoworld.com)

A seven-part CME video course about liver sonography provided by SonoWorld (www.sonoworld.com) at http://is.gd/pWFqJm also available on YouTube (no CME credit) at http://is.gd/h2tCAR

Portal venous system and its tributaries: a radial endosonographic assessment (Spring Publishing) http://is.gd/kpCjxu

Gallbladder lesions identified on ultrasound. Lessons from the last 10 years (J Gastrointest Surg, 2011) http://is.gd/rUchI6

Stage information for extrahepatic bile duct cancer (National Cancer Institute) http://is.gd/cXDq09

Stage information for gallbladder cancer (National Cancer Institute) http://is.gd/UbIDBf

Stage information for adult primary liver cancer (National Cancer Institute) http://is.gd/GFX2Qp

Endoscopic Ultrasound (journal) http://www.eusjournal.com

5.2 Cases and Discussions

5.2.1 Gallbladder

5.2.1.1 Cholecystitis and Cholelithiasis

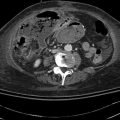

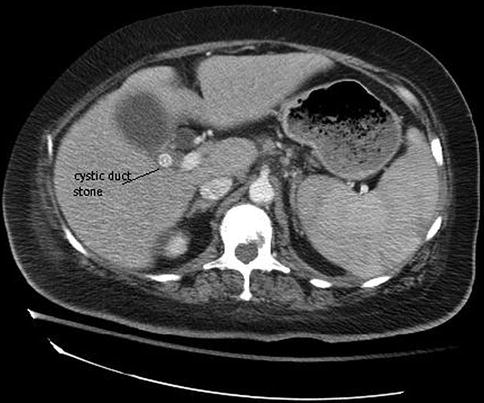

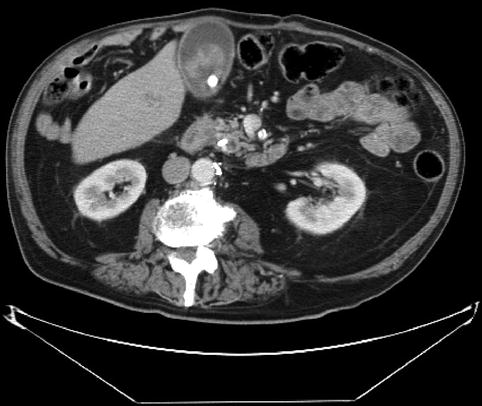

This is a 59-year-old patient with widely metastatic breast cancer who developed severe abdominal pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen shows a stone impacted in the cystic duct. A hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan revealed nonfilling of the gallbladder. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed to rule out a common bile duct stone because the patient’s bilirubin level was mildly elevated. No stone was seen in the common bile duct. The interesting abnormality in the distal common bile duct (choledochocele vs. web) is discussed in the Liver section of this chapter. The EUS images (Fig. 5.5) show echogenic bile and a thickened gallbladder wall but no pericholecystic fluid and no stones in the gallbladder itself. During surgery the gallbladder was densely adherent to the liver and filled with pus. A stone was stuck in the cystic duct.

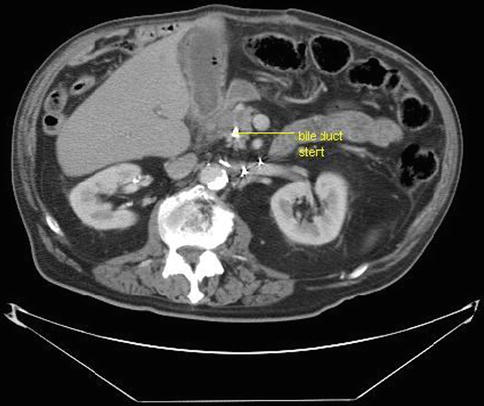

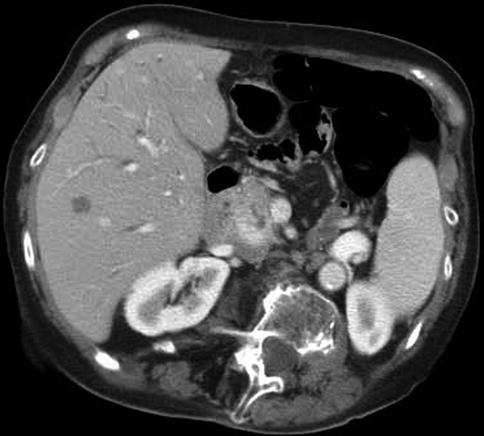

Fig. 5.1

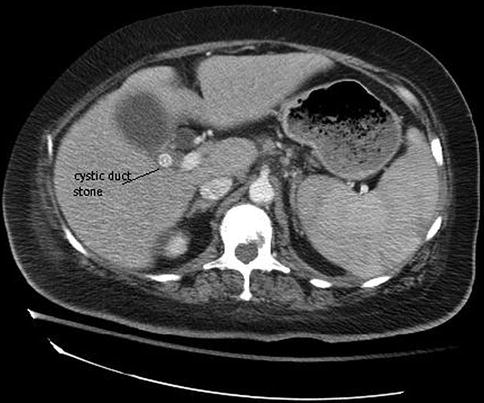

This computed tomography scan shows a stone obstructing the cystic duct

Fig. 5.2

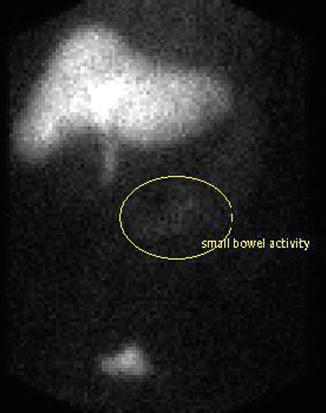

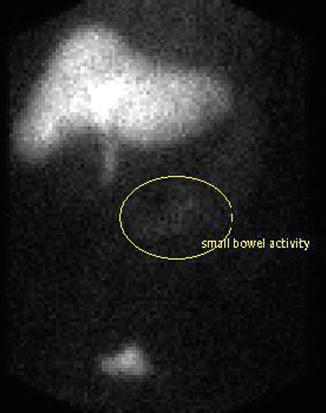

This HIDA scan shows activity in the small intestine and urinary bladder but not in the gallbladder

Fig. 5.3

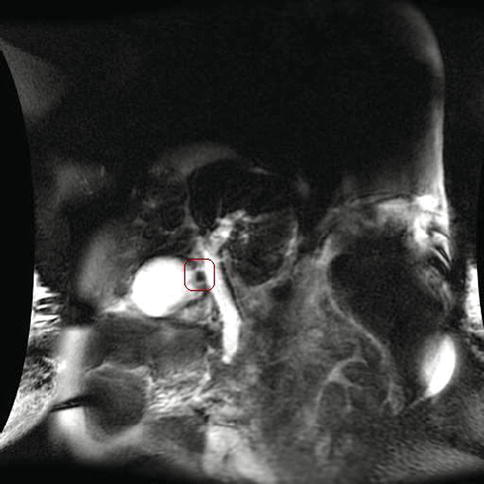

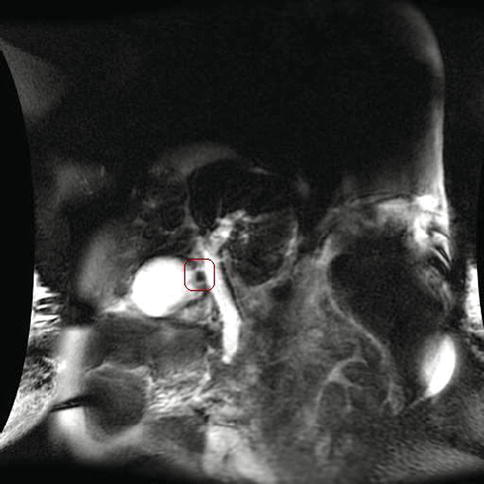

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows a stone in the cystic duct and an abnormality of the distal common bile duct

Fig. 5.4

Endoscopic ultrasound shows a greatly dilated cystic duct, consistent with obstruction

Fig. 5.5

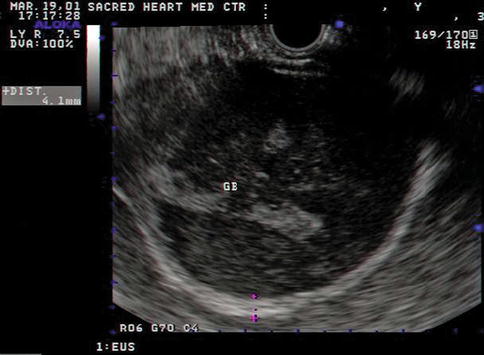

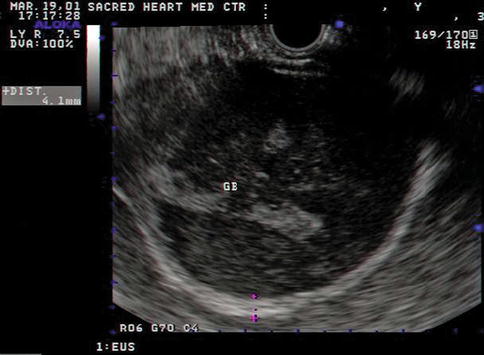

Endoscopic ultrasound showing the gallbladder (GB) filled with echogenic bile. During surgery it was found to contain pus. Note the thickening of the gallbladder wall

5.2.1.2 Gallbladder Carcinoma

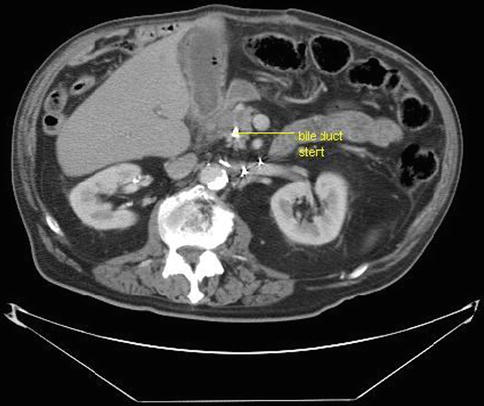

When diagnosed incidentally during cholecystectomy, surgical resection can be curative. However, most often the tumor is unresectable at the initial presentation of the patient. Fortunately, gallbladder cancer is rare in North America. The highest incidence of gallbladder cancer is found among Andean populations, North American Indians, and Mexican Americans [3]. Early diagnosis could improve the clinical outcome and cure rate. However, conventional imaging modalities such as transcutaneous abdominal ultrasound and CT can be difficult to interpret, as this case shows. This is an 84-year-old patient who initially presented with obstructive jaundice. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) performed by a different examiner revealed a stricture of the common hepatic duct, which was stented. The gallbladder did not fill. The abnormalities on the CT scan suggesting a gallbladder mass were initially not appreciated, presumably because there were other more impressive things to be seen, such as a large pseudocyst. A HIDA scan was ordered and showed nonfilling of the gallbladder. Cholecystitis was suspected and, because of the patient’s debilitated state, arrangements were made for the placement of a cholecystotomy tube. Fortunately, an EUS also was requested and showed an obvious gallbladder cancer. The cholecystomy tube was not placed.

EUS typically uses higher scanning frequencies than transcutaneous abdominal ultrasound (5–10 vs. 2–5 MHz) and can visualize the gallbladder from a closer distance (from the antrum or duodenal bulb), providing more detailed views of gallbladder abnormalities, including a double-layer wall ultrasound pattern [4]. A gallbladder wall thicker than 10 mm, disruption of the normal two layers of the gallbladder wall, hypoechoic internal echogenicity, and the absence of gallstones were found to correlate with gallbladder neoplasia [4].

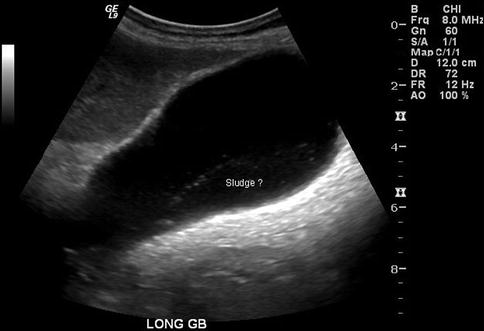

Fig. 5.6

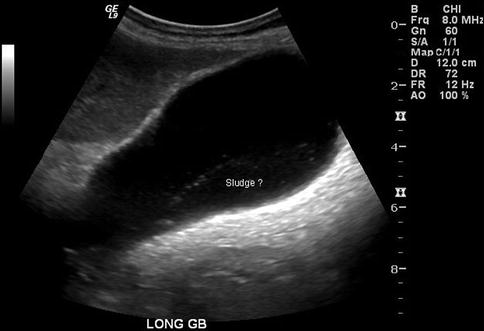

This transabdominal ultrasound shows “sludge” that is somewhat lumpy and does not seem to layer well in a dependent position. GB gallbladder

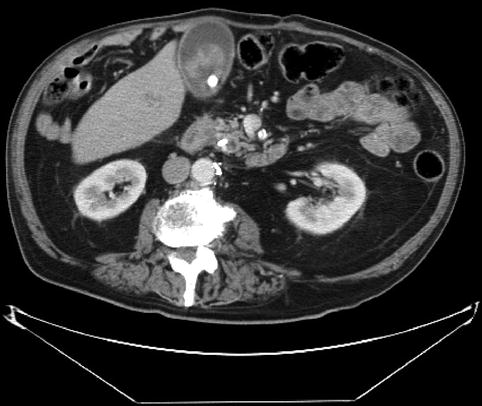

Fig. 5.7

A stone in the gallbladder and intraluminal tissue that enhances with intravenous contrast is seen on this computed tomography scan. However, these were not initially reported

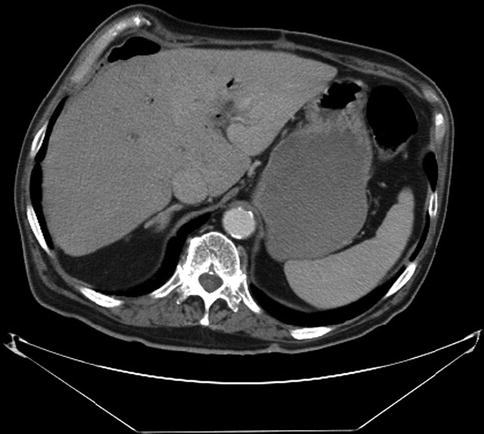

Fig. 5.8

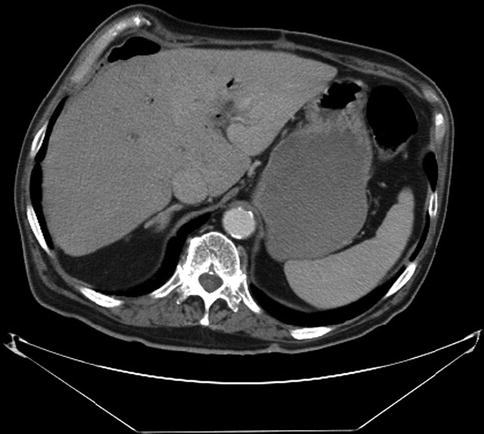

This large pseudocyst diverted attention from the gallbladder

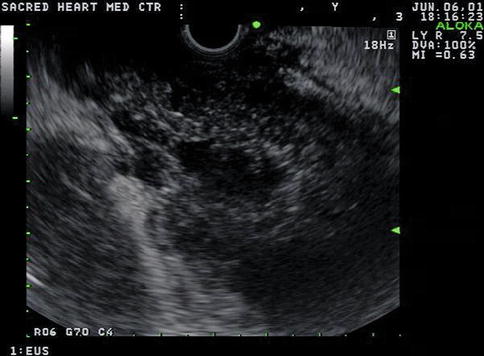

Fig. 5.9

This linear endoscopic ultrasound image shows the gallbladder stone (casting a large shadow) surrounded by hypoechoic tissue

Fig. 5.10

This linear endoscopic ultrasound image shows that the entire gallbladder is filled with tumor tissue

Fig. 5.11

This radial endoscopic ultrasound image shows that the gallbladder tumor (gb tu) extends from the gallbladder to the extrahepatic bile ducts

Fig. 5.12

This computed tomography scan shows the bile duct stent surrounded by tumor

5.2.1.3 Gallbladder Cysts

Intramural cysts of the gallbladder are rare; according to one case report only 13 cases have been reported in the world literature up to 2002 [4]. Here we present is an elderly patient who was sent to us for EUS evaluation of a dilated main pancreatic duct. The pancreas was otherwise normal. The cystic lesion in the gallbladder was incidentally found. The EUS clearly shows the epithelial origin of the cyst.

Fig. 5.13

Transverse section through the gallbladder showing the epithelial cyst

Fig. 5.14

The same gallbladder cyst as in Fig. 5.13 seen in a longitudinal section

5.2.1.4 Courvoisier’s Sign

Courvoisier’s law states that in the presence of a palpable gallbladder, jaundice is unlikely to be caused by gallstones. However, Courvoisier was not quite as dogmatic. Here is what he actually wrote in his Treatise on the Pathology and Surgery of the Biliary Passages (translated from the German) [5]:

Obstruction by stone is supported by

1.

prior (self-limited) jaundice attacks

2.

continuing but fluctuating jaundice

3.

jaundice present for years

4.

prior typical biliary colic attacks, especially if they were associated with jaundice

5.

previous passage of gallstones

6.

no or only mild distention of the gallbladder

7.

fever with more or less intermittent character

Obstructions of other types are indicated by the lack of these characteristics and most importantly by the presence and considerable size of a distended gallbladder [5].

This is a 61-year-old patient with obstructive jaundice secondary to cancer of the pancreatic head who has a very dilated gallbladder.

Fig. 5.15

Sagittal reconstruction of a computed tomography scan of a patient with an obstruction of the distal common bile duct caused by a pancreatic cancer and a typical Courvoisier gallbladder

Fig. 5.16

The same distended Courvoisier gallbladder as in Fig. 5.15, seen with a linear array echoendoscope. Note the microcrystals

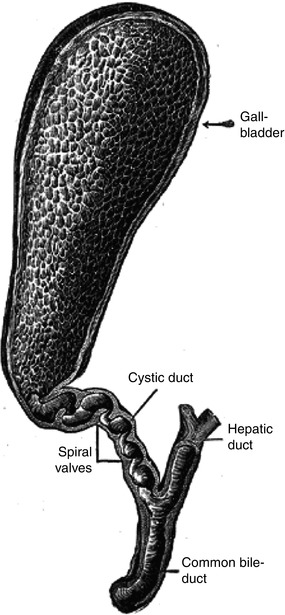

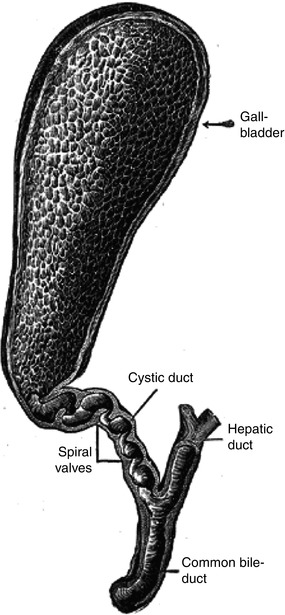

5.2.1.5 Heister Valves

The function of the spiral mucosal folds seen in the cystic duct are unknown. The duct and spiral folds contain muscle fibers that apparently respond to a variety of stimuli but there is no discrete muscular sphincter. It is speculated that the spiral valves are mechanical devices that keep the tortuous cystic duct patent. During endosonography the Heister valves can sometimes be demonstrated.

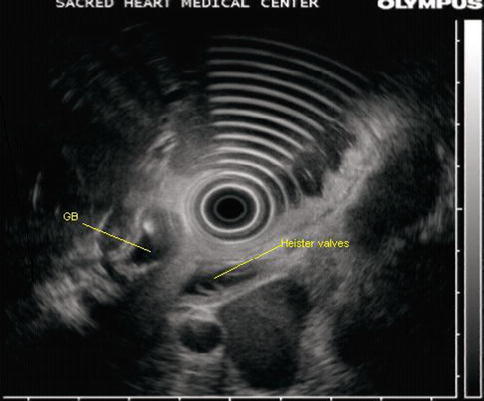

Fig. 5.17

This image shows the Heister or spiral valves in the cystic duct (From Wikimedia Commons)

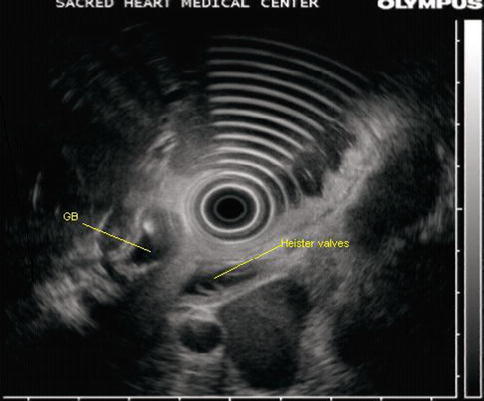

Fig. 5.18

Heister valves in an unusually prominent cystic duct. GB gallbladder

5.2.2 Liver

5.2.2.1 A Growing Subhepatic Cyst

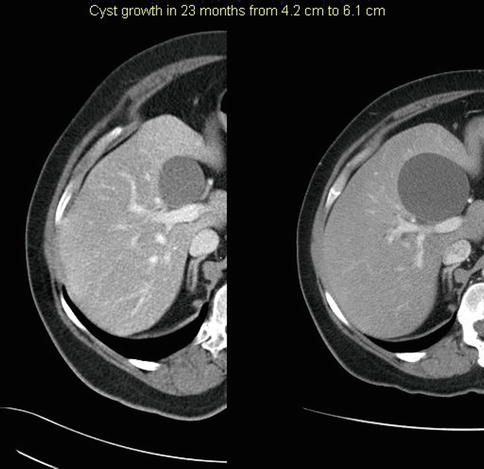

This is a 40-year-old woman with a symptomatic subhepatic cyst initially believed to be a choledochalcyst. The size of the cyst increased significantly over the course of 2 years and the patient eventually became deeply jaundiced. A preoperative CT scan surprisingly showed no connection to the biliary system, but the cyst caused extrinsic compression of the biliary tree. The excised cyst was lined by a squamous epithelium, an unusual feature, but contained no malignancy. Choledochal cysts are lined by a biliary-type epithelium but often have focal or extensive squamous metaplasia in response to chronic inflammation. The exact taxonomy of this cyst remains unclear but is does not appear to derive from the biliary tree. There are several reviews about common presentations, diagnostic methods, and treatment of congenital and acquired liver cysts [6, 7].

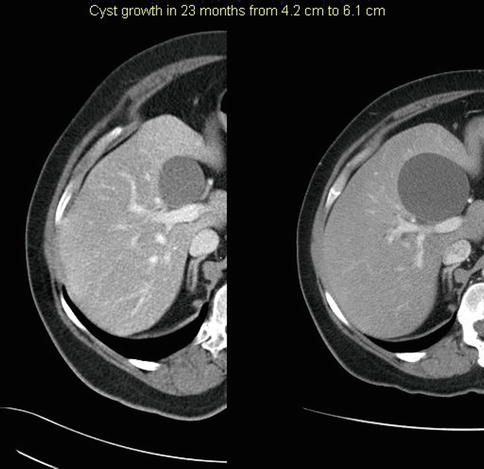

Fig. 5.19

These computed tomography scans show a growing subhepatic cyst, from baseline (left) to 23 months later (right)

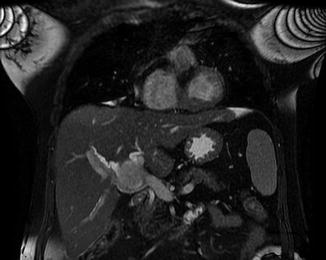

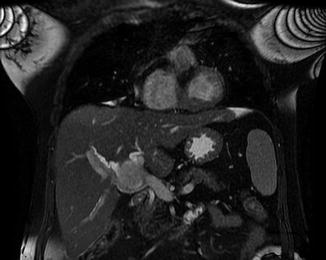

Fig. 5.20

This coronal magnetic resonance imaging section appears to show displacement of the right hepatic duct

Fig. 5.21

The compression of the right hepatic duct by the cyst can be seen during the initial stages of dye injection. Air bubbles are present in the distal common bile duct

Fig. 5.22

After complete filling, a mass effect on the hilar structures is still apparent; more important is that the cystic structure does not fill with dye, indicating that there is no communication with the biliary system

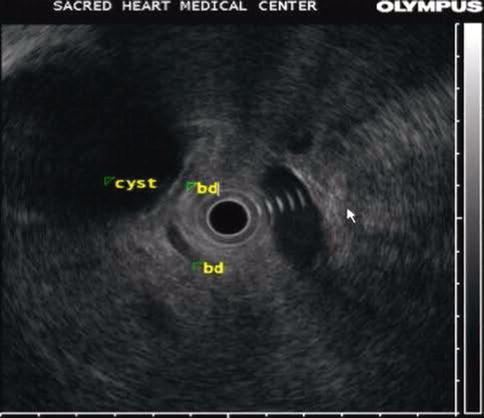

Fig. 5.23

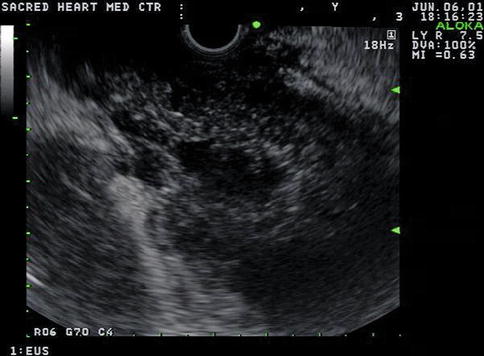

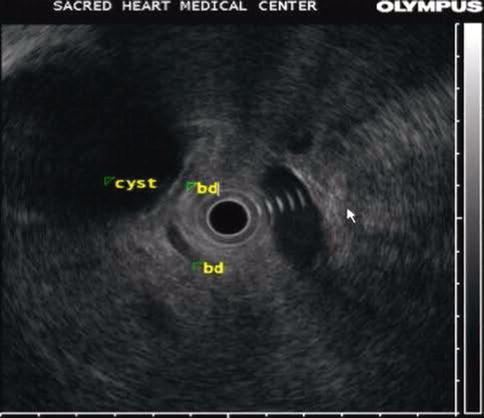

Endoscopic ultrasound shows a cyst with typical posterior enhancement, layering sludge, and a faint central filamentous structure (horizontally in the middle of the cyst)

Fig. 5.24

The bile duct (bd) is intimately associated with the cyst and compressed

5.2.2.2 Hemangioma

Typical ultrasound features of hepatic hemangiomas are their small size, uniform hyperechogenicity, well-defined margins, and posterior echo enhancement. These typical characteristics are modified as the hemangioma grows larger.

Not all hemangiomas are hyperechoic. In one recent large series, hepatic hemangiomas diagnosed with contrast-enhanced CT were classified by internal echo pattern as homogeneous hyperechoic (35.0 %), homogeneous hypoechoic (22.9 %), isoechoic (5.2 %), mixed hyperechoic (22.1 %), or mixed hypoechoic (14.8 %) [8].

Fig. 5.25

This image, taken with the GF-UM160 echoinstrument, shows two hemangiomas: a small one and a large one located in the periphery

Fig. 5.26

This image puts the smaller of the two lesions into focus. Hemangiomas are sharply demarcated, round, echogenic lesions that typically measure from 1 to 3 cm in diameter

Fig. 5.27

This computed tomography scan shows the smaller of the two hemangiomas

Fig. 5.28

This coronal reconstruction reveals calcifications in a large peripheral hemangioma

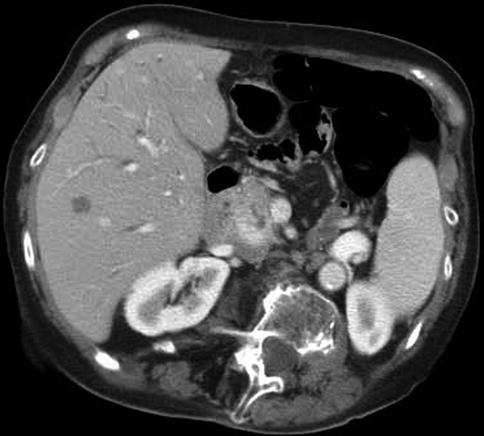

5.2.2.3 Hepatoma

Hepatomas, especially small ones, are difficult to diagnose or biopsy. Obviously, some segments of the liver are not accessible by EUS. Nevertheless, EUS should be considered when the lesions are within the reach of the echoendoscope. The valuable role EUS can play in the detection and biopsy of small hepatomas that are not well visualized or would be difficult to access by percutaneous ultrasound is increasingly being recognized [9]. According to published retrospective series, EUS-guided FNA provides adequate tissue for diagnosis and with minimal risk of complications [10]. Moreover, metastatic lesions, especially to lymph nodes, can also easily be biopsied as this next case and others show [11]. This patient is a 51-year-old man with a history of chronic liver disease who had increasing alpha-fetoprotein levels and large bilateral adrenal masses without known liver lesions. An initial EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) could not be completed because of problems during sedation. The study did, however, show liver lesions suspicious for hepatoma that were not previously recognized by CT. Magnetic resonance imaging also demonstrated the lesions seen during EUS. During a subsequent EUS with anesthesia support, FNA biopsies or aspirates were obtained from two liver lesions (showing hepatoma), ascites (negative), the left adrenal lymph node (benign), and two small perigastric lymph nodes (metastatic hepatoma).

Fig. 5.29

This large left adrenal mass was biopsied but only bland adrenocortical type cells were seen. L KID left kidney

Fig. 5.30

There was a moderate amount of ascites with negative cytology

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree