Etiology

Gastric outlet obstruction is an uncommon clinical consequence with a wide range of causes. Benign and malignant as well as gastric and extragastric causes have been described. It was once relatively common to see patients present with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to inflammation or scarring from peptic ulcer disease (up to 12%). Although it is difficult to define with certainty the incidence of gastric outlet obstruction, it is thought to have likely declined as treatments have improved for gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Since the introduction of histamine-2 (H 2 ) blockers, malignant causes now represent the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction overall.

Peptic ulcer disease remains the most common benign cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Other benign causes include gastric and gastroduodenal bezoars, Crohn’s disease, hyperplastic or eosinophilic gastroenteritis, heterotopic pancreatic tissue within the antrum or duodenal bulb, gastric volvulus, obstructing gallstone (also known as Bouveret’s syndrome), and pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocysts. Unusual benign causes that have been described in the literature include Brunner’s gland hyperplasia ( Figure 22-1 ), gastroduodenal tuberculosis, and neurofibromatosis. Gastric outlet obstruction is rare in the pediatric population and includes such benign causes as antral and pyloric atresia, antral and pyloric webs, gastric and gastroduodenal lactobezoars, and pyloric duplication cysts.

Malignant causes now represent the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in the adult population. Neoplasms that can cause gastric outlet obstruction include gastric adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and gallbladder carcinoma. In these cases, gastric outlet obstruction may be a presenting manifestation of the disease or may be caused by inflammation or scarring from treatments such as radiation therapy.

The role of imaging and interventional radiology in the diagnosis and treatment of gastric outlet obstruction depends on the underlying cause. Most commonly, when a patient presents with symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction, including intractable vomiting, “food fear,” and cachexia, some of the first diagnostic studies are abdominal radiography and CT. It is relatively straightforward to make a diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction using these modalities, but the more difficult task remains in determining what may be the culprit in any individual patient. Some of the causes have classic imaging findings on CT (e.g., gastric bezoar ), and some will likely be easy to diagnose (e.g., advanced pancreatic neoplasm). However, it is also likely that the underlying causes may not be readily ascertained by the initial imaging study (e.g., as in the case of gastric lymphoma). For this reason, it is important to keep in mind not only the different causes of gastric outlet obstruction but also the epidemiology of these entities to better tailor a differential diagnosis.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of gastric outlet obstruction is difficult to determine secondary to the wide variety of underlying causes. It may be easier to consider how often each of the possible causes, both benign and malignant, manifest as gastric outlet obstruction.

In the adult population, malignant causes are the most common, followed by benign peptic ulcer disease. Studies have indicated that the incidence of people presenting with advanced peptic ulcer disease has decreased with the advances in treatment, including H 2 blockers. Presumably, as this once-common entity and presentation has become rarer, the overall incidence of gastric outlet obstruction also has likely decreased. This, however, has not been studied in the literature.

Currently, the most common causes of gastric outlet obstruction in the adult are malignant. Up to 35% of patients with gastric cancer present with gastric outlet obstruction, but the incidence of this is thought to be decreasing in the developed world. Of patients with pancreatic cancer, 15% to 25% present with gastric outlet obstruction and typically these patients also will have signs and symptoms of biliary obstruction.

In the pediatric population, malignant causes are unlikely. Benign causes that may be seen in younger patients include congenital causes (pyloric stenosis, antral webs, and duplication cysts), inflammatory processes (pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocyst), and acquired obstruction (foreign body, bezoar).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of gastric outlet obstruction is difficult to determine secondary to the wide variety of underlying causes. It may be easier to consider how often each of the possible causes, both benign and malignant, manifest as gastric outlet obstruction.

In the adult population, malignant causes are the most common, followed by benign peptic ulcer disease. Studies have indicated that the incidence of people presenting with advanced peptic ulcer disease has decreased with the advances in treatment, including H 2 blockers. Presumably, as this once-common entity and presentation has become rarer, the overall incidence of gastric outlet obstruction also has likely decreased. This, however, has not been studied in the literature.

Currently, the most common causes of gastric outlet obstruction in the adult are malignant. Up to 35% of patients with gastric cancer present with gastric outlet obstruction, but the incidence of this is thought to be decreasing in the developed world. Of patients with pancreatic cancer, 15% to 25% present with gastric outlet obstruction and typically these patients also will have signs and symptoms of biliary obstruction.

In the pediatric population, malignant causes are unlikely. Benign causes that may be seen in younger patients include congenital causes (pyloric stenosis, antral webs, and duplication cysts), inflammatory processes (pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocyst), and acquired obstruction (foreign body, bezoar).

Clinical Presentation

The hallmark of gastric outlet obstruction is nausea and intractable vomiting. Typically, the vomiting is nonbilious and may contain undigested food particles. Depending on the underlying cause, the patient may present with pain, particularly in peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, or Bouveret’s syndrome. In patients with malignancy as the cause for gastric outlet obstruction, early satiety and weight loss are frequent symptoms. These also can be seen in patients with chronic causes such as gastric bezoars.

With severe gastric outlet obstruction, the abdomen may be distended with a tympanic left upper quadrant. Depending on the underlying cause, physical examination may yield additional clues. Patients with underlying progressive malignancies may be cachectic or jaundiced in the case of pancreatic and biliary malignancies. In patients with peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, or obstruction caused by gallstones, there will be associated pain to palpation. In the infant with pyloric stenosis, the classically described physical examination finding is an “olive” in the upper abdomen. Finally, in patients with trichobezoars, hair loss from constant pulling may be found.

Abnormal laboratory values may be associated with gastric outlet obstruction if the patient has had long-standing vomiting causing dehydration or malnutrition. Vomiting causes loss of hydrochloric acid and can lead to metabolic alkalosis. Additionally, if the patient has progressed to dehydration, abnormalities of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine may be present. Finally, any laboratory abnormalities associated with the underlying cause of the gastric outlet obstruction also may be seen. These include a positive test for Helicobacter pylori in cases of peptic ulcer disease, elevated amylase and lipase levels in pancreatitis, an elevated bilirubin level in cases of obstructive jaundice secondary to pancreatic neoplasm, and anemia in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer disease, underlying malignancy, or chronic disease such as Crohn’s disease or tuberculosis.

Imaging

The general manifestations of gastric outlet obstruction are nausea and intractable vomiting. In more severe or chronic cases, cachexia and food aversion may be seen. Differential considerations for this broad spectrum of symptoms can be narrowed with evaluation of patient age, physical examination, laboratory data, diagnostic imaging, and endoscopic evaluation if necessary.

Radiography

Abdominal radiography may show a dilated stomach, which can displace bowel inferiorly (see Figure 22-1 ). Barium upper gastrointestinal studies may show the site of obstruction. Narrowing of the distal portion of the stomach can help differentiate gastric outlet obstruction from functional gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying. In the acute setting, barium upper gastrointestinal studies are rarely performed. In more chronic cases, if a double-contrast barium study is performed, an ulcer or intrinsic mass that is large enough to cause gastric outlet obstruction should be readily seen.

Computed Tomography

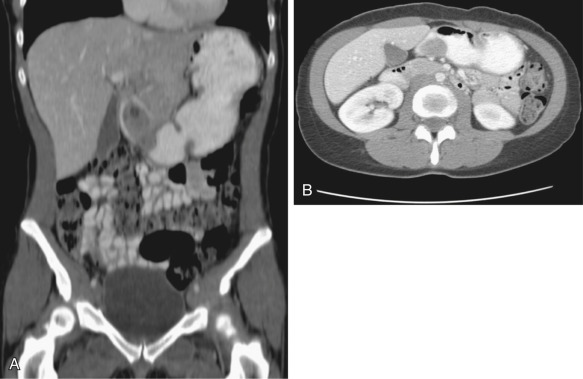

CT is the most useful imaging modality for both the diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction and the differentiation of its many underlying causes. On CT, gastric outlet obstruction is seen as a large dilated stomach. If an oral contrast agent has been administered, little of it will have progressed past the site of obstruction.

More useful is CT’s role in differentiating the underlying causes of gastric outlet obstruction. Malignant processes such as pancreatic cancer can be diagnosed using CT, particularly if it progressed enough to cause gastric outlet obstruction ( Figure 22-2 ). Benign causes such as pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocyst ( Figure 22-3 ), bezoar, and Bouveret’s syndrome can also be differentiated.