Stromal tumors of the stomach are rare tumors that arise from the mesenchyma, the connective tissue and blood vessels that support an organ. The parenchyma, on the other hand, represents the functional tissue of the organ. Within the stomach, the parenchyma includes the epithelial glandular tissue within the mucosa and the mesenchyma consists of the supporting tissues, or stroma. The components of the stroma include smooth muscle cells, nerve cells, lipocytes, vascular structures, and epithelioid cells. Gastric stromal tumors arise from these cell types.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The prevalence of gastric stromal tumors varies by type. The most common is the gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), with 10 to 20 cases per million persons, representing 5000 to 6000 cases in the United States annually. GISTs make up 2% to 3% of all gastric tumors. Lipomas represent 2% to 3% of benign gastric tumors, neurogenic tumors account for 4%, and vascular tumors comprise 2%. The remainder of the gastric stromal tumors are exceedingly rare.

There is an increased risk for GIST with neurofibromatosis, Carney’s syndrome, and germline mutations of KIT.

Pathology

Historically, GISTs were referred to as leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, epithelioid leiomyosarcoma, and leiomyoblastomas, based on the thought that the tumors arise from smooth muscle cells. However, it is now felt that GISTs arise from the interstitial cell of Cajal, which is a primitive gut stem cell in the muscularis propria that expresses KIT, a tyrosine kinase receptor. Distinguishing GIST from other stromal tumors is by the expression of KIT, and 95% of GISTs express KIT. CD117 immunohistochemistry stains are positive for KIT and are diagnostic of GIST. The expression of KIT in GIST is the premise behind medical therapy.

GISTs can be benign or malignant. The determination of a benign or malignant GIST is based on the number of mitoses observed per high-power field. Malignant GISTs can recur and metastasize to the liver and peritoneal surface, with distant metastasis being rare. Metastatic GISTs do not manifest with lymphadenopathy. Therefore, if lymphadenopathy is present, other malignant tumors, such as adenocarcinoma and lymphoma, should be considered.

Other gastric stromal tumors are diagnosed histologically. Schwannomas stain positive for S-100 protein. True leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas arise from smooth muscle cells and are rare in the stomach.

Imaging

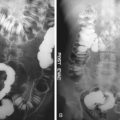

Seventy percent of GISTs are found in the stomach ( Figure 21-1 ), and 75% of these are found in the body. GISTs also can be found anywhere from the esophagus to the anus and can arise from the mesentery, retroperitoneum, and omentum. The second most common site of presentation is within the small bowel, representing 20% to 30% of cases. Other stromal tumors mimic the appearance of GIST and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Computed Tomography

On CT, GISTs are usually peripherally contrast enhancing and often will have extragastric and intragastric components. Given their size, it is often difficult to determine which portion of the bowel the GIST arises from, but subtle bowel wall thickening can be a clue. Cavitation and calcification are uncommon findings ( Figure 21-2 ).

No definite imaging criteria have been established to distinguish benign from malignant GIST. Initially, it was found that besides evidence of metastatic disease, only size greater than 5 cm was predictive of malignancy. Recently, however, it has been suggested that heterogeneous enhancement and a cystic-necrotic component can be found with a GIST with malignant potential. Metastatic disease from GISTs are often confined to the liver and mesentery, with predominantly hypervascular metastasis.

Gastric adenocarcinoma and lymphoma do not often have extragastric components, and that can be used as a clue for diagnosis. Other benign stromal tumors are much rarer, and imaging characteristics are nonspecific but are also in the differential diagnosis. However, gastric schwannomas, for example, may be suspected if there is homogenous enhancement of a well-circumscribed mass. A smooth, well-circumscribed mass measuring −70 to −120 Hounsfield units is diagnostic of gastric lipoma.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of GISTs mimics that of CT. The lesions usually will have increased T1 signal in the solid areas and increased T2 signal in the cystic areas. The mass can be heterogeneous because of the presence of hemorrhage. GISTs usually enhance and also demonstrate hypervascular metastases.

Uniformly high T1 signal in a submucosal mass is consistent with a lipoma. Only a single case of MRI of gastric schwannoma has been reported, which described uniform enhancement of a lobulated, low-T1 signal, high-T2 signal well-circumscribed mass.

Positron Emission Tomography with Computed Tomography

GISTs and metastases generally demonstrate high fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) activity. PET has been used for both staging and follow-up for treatment of GIST ( Figure 21-3 ). PET is especially helpful in monitoring the response to imatinib (Gleevac). In patients treated with imatinib, marked decrease in FDG activity has been observed shortly after treatment is initiated, which is further described in the medical treatment section.