Chapter THREE

Gastrointestinal Imaging

RENDON C. NELSON  CHAPTER EDITOR

CHAPTER EDITOR

VINCENT H.S. LOW

HISTORY

A 28-year-old man presents with odynophagia.

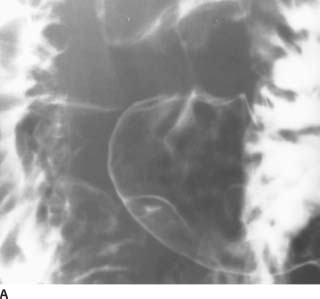

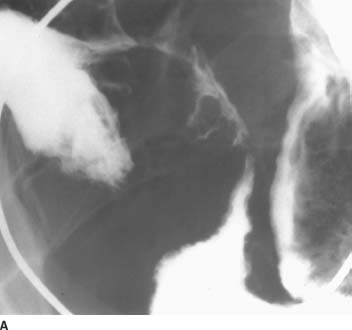

FIGURE 3-1A Barium swallow: Mucosal relief view of the mid to distal esophagus. There is a large (3 cm), shallow ulcer, sometimes given the term“giant”ulcer, in the mid to distal esophagus. The floor of the ulcer appears clean and smooth. There is no evidence of a mass, mucosal irregularity, infiltration, or rigidity.

FIGURE 3-1A Barium swallow: Mucosal relief view of the mid to distal esophagus. There is a large (3 cm), shallow ulcer, sometimes given the term“giant”ulcer, in the mid to distal esophagus. The floor of the ulcer appears clean and smooth. There is no evidence of a mass, mucosal irregularity, infiltration, or rigidity.

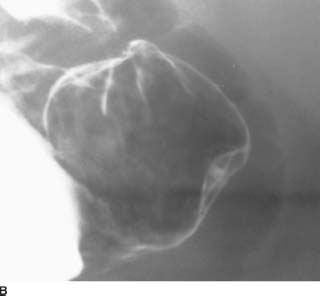

FIGURE 3-1B Barium swallow: Detail distended view of the lesion at the junction of the mid to distal esophagus. The ulcer has a well-defined lucent rim, suggesting that it is benign.

FIGURE 3-1B Barium swallow: Detail distended view of the lesion at the junction of the mid to distal esophagus. The ulcer has a well-defined lucent rim, suggesting that it is benign.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease: This is the most common cause of esophageal ulceration, and such a large proximal ulcer raises the possibility of Barrett’s change.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease: This is the most common cause of esophageal ulceration, and such a large proximal ulcer raises the possibility of Barrett’s change.

Infectious esophagitis: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) should be suspected in the immunocompromised patient. The fact that this is a young patient makes this condition more likely. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) itself can also result in giant esophageal ulcers.

Infectious esophagitis: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) should be suspected in the immunocompromised patient. The fact that this is a young patient makes this condition more likely. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) itself can also result in giant esophageal ulcers.

Medication-induced esophagitis: A history of recent ingestion of certain medications (particularly tetracycline antibiotics) would be relevant.

Medication-induced esophagitis: A history of recent ingestion of certain medications (particularly tetracycline antibiotics) would be relevant.

Radiation esophagitis: Close anatomic relationship of the area of ulceration to the portal of radiation therapy would be relevant.

Radiation esophagitis: Close anatomic relationship of the area of ulceration to the portal of radiation therapy would be relevant.

DIAGNOSIS

CMV esophagitis

KEY FACTS

Clinical

CMV is a member of the herpes virus group. It causes opportunistic esophagitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and only rarely in other immunocompromised patients.

CMV is a member of the herpes virus group. It causes opportunistic esophagitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and only rarely in other immunocompromised patients.

Patients usually present with odynophagia, which may be severe. On endoscopy, ulcerative esophagitis is seen with lesions that may be shallow or deep. It is impossible to differentiate this disorder from other viral esophagitides, including involvement by the HIV itself.

Patients usually present with odynophagia, which may be severe. On endoscopy, ulcerative esophagitis is seen with lesions that may be shallow or deep. It is impossible to differentiate this disorder from other viral esophagitides, including involvement by the HIV itself.

Diagnosis is made from endoscopic brushings or biopsy specimens from the base of ulcers, by microscopic detection of characteristic intranuclear inclusion bodies in endothelial cells or fibroblasts, or by positive viral cultures. Histologic findings are required to differentiate CMV from herpetic esophagitis. HIV ulcers may respond to the administration of steroids, but CMV esophagitis requires antiviral agents such as ganciclovir.

Diagnosis is made from endoscopic brushings or biopsy specimens from the base of ulcers, by microscopic detection of characteristic intranuclear inclusion bodies in endothelial cells or fibroblasts, or by positive viral cultures. Histologic findings are required to differentiate CMV from herpetic esophagitis. HIV ulcers may respond to the administration of steroids, but CMV esophagitis requires antiviral agents such as ganciclovir.

Radiologic

CMV esophagitis may appear as discrete, small, superficial ulcers similar to those of herpes. Occasionally, a nonspecific esophagitis with nodular thickened folds only is seen, which may simulate reflux esophagitis.

CMV esophagitis may appear as discrete, small, superficial ulcers similar to those of herpes. Occasionally, a nonspecific esophagitis with nodular thickened folds only is seen, which may simulate reflux esophagitis.

Giant, flat, single, or multiple ulcers, often with a thin radiolucent rim of edematous mucosa, are very suggestive of CMV esophagitis. These ulcers may be several centimeters in length and appear ovoid because of the limited diameter of the esophagus.

Giant, flat, single, or multiple ulcers, often with a thin radiolucent rim of edematous mucosa, are very suggestive of CMV esophagitis. These ulcers may be several centimeters in length and appear ovoid because of the limited diameter of the esophagus.

HIV ulcers may have an identical radiologic appearance, requiring endoscopy and biopsy for culture and histologic examination to make a definitive diagnosis before appropriate treatment can commence.

HIV ulcers may have an identical radiologic appearance, requiring endoscopy and biopsy for culture and histologic examination to make a definitive diagnosis before appropriate treatment can commence.

Candida esophagitis is characterized by longitudinally orientated, small, plaque-like filling defects. Severe disease appears as extensive, confluent, large plaques, giving the mucosa a“shaggy”pattern. These patterns are not typical for CMV, allowing radiologic differentiation.

Candida esophagitis is characterized by longitudinally orientated, small, plaque-like filling defects. Severe disease appears as extensive, confluent, large plaques, giving the mucosa a“shaggy”pattern. These patterns are not typical for CMV, allowing radiologic differentiation.

SUGGESTED READING

Balthazar EJ, Megibow AJ, Hulnick D, et al. Cytomegalovirus esophagitis in AIDS: radiographic features in 16 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:919–923.

Sor S, Levine MS, Kowalski TE, et al. Giant ulcers of the esophagus in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: clinical, radiographic and pathologic findings. Radiology 1995;194:447–451.

Yee J, Wall SD. Infectious esophagitis. Radiol Clin North Amer 1994;32: 1135–1145.

DAVID M. HOUGH

HISTORY

A 55-year-old man presents with dysphagia.

FIGURE 3-2 Barium swallow: Spot film of the upper esophagus in single contrast. There are multiple, small, flask-shaped outpouchings from the esophageal lumen. Where visible, the neck of these outpouchings is very narrow.

FIGURE 3-2 Barium swallow: Spot film of the upper esophagus in single contrast. There are multiple, small, flask-shaped outpouchings from the esophageal lumen. Where visible, the neck of these outpouchings is very narrow.

Intramural pseudodiverticulosis: The finding of multiple flask-shaped collections of barium, oriented almost perpendicular to the long axis of the esophagus, is characteristic of this condition. Not all of the pseudodi-verticula show a clear communication with the esopha-geal lumen.

Intramural pseudodiverticulosis: The finding of multiple flask-shaped collections of barium, oriented almost perpendicular to the long axis of the esophagus, is characteristic of this condition. Not all of the pseudodi-verticula show a clear communication with the esopha-geal lumen.

Esophagitis: Features may include fold thickening, mucosal nodularity, an irregular mucosal contour, and focal erosions or ulcers. Ulcers can usually be seen to clearly communicate with the esophageal lumen, whereas in this case, some of the barium collections do not communicate. There are no plaque-like filling defects, as may be seen with Candida and other causes of esophagitis.

Esophagitis: Features may include fold thickening, mucosal nodularity, an irregular mucosal contour, and focal erosions or ulcers. Ulcers can usually be seen to clearly communicate with the esophageal lumen, whereas in this case, some of the barium collections do not communicate. There are no plaque-like filling defects, as may be seen with Candida and other causes of esophagitis.

True esophageal diverticula: True diverticula are larger and less numerous than pseudodiverticula.

True esophageal diverticula: True diverticula are larger and less numerous than pseudodiverticula.

DIAGNOSIS

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticula

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticula is caused by dilated excretory ducts of the deep esophageal mucous glands, due to chronic inflammation. It is usually a sequela of chronic reflux esophagitis. Secondary infection with Candida is a common associated finding, but it is not considered a causal factor.

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticula is caused by dilated excretory ducts of the deep esophageal mucous glands, due to chronic inflammation. It is usually a sequela of chronic reflux esophagitis. Secondary infection with Candida is a common associated finding, but it is not considered a causal factor.

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticula most commonly occurs in elderly patients, with a slight male predominance. In as many as 90% of cases, there is an associated stricture. The most common presenting symptom is dysphagia, due to the associated stricture, and management is directed at treating the stricture.

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticula most commonly occurs in elderly patients, with a slight male predominance. In as many as 90% of cases, there is an associated stricture. The most common presenting symptom is dysphagia, due to the associated stricture, and management is directed at treating the stricture.

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticula occurs in approximately 0.1% of patients undergoing barium esophagography, with an increased prevalence in patients with esophageal cancer (4.5%).

Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticula occurs in approximately 0.1% of patients undergoing barium esophagography, with an increased prevalence in patients with esophageal cancer (4.5%).

Radiologic

Single-contrast barium examination with low-density barium, which more readily enters the gland ducts, is more sensitive than a double-contrast technique with high-density barium for detecting intramural pseudodi-verticula. Endoscopy is relatively insensitive because it is difficult to visualize the tiny duct orifices.

Single-contrast barium examination with low-density barium, which more readily enters the gland ducts, is more sensitive than a double-contrast technique with high-density barium for detecting intramural pseudodi-verticula. Endoscopy is relatively insensitive because it is difficult to visualize the tiny duct orifices.

The characteristic appearance is that of numerous small (1 to 4 mm), flask-shaped outpouchings from the esophagus. The tiny necks may not fill completely, resulting in an apparent lack of communication with the esophageal lumen.

The characteristic appearance is that of numerous small (1 to 4 mm), flask-shaped outpouchings from the esophagus. The tiny necks may not fill completely, resulting in an apparent lack of communication with the esophageal lumen.

Distribution is more often segmental than diffuse. Pseu-dodiverticula may occur at, above, or below the level of a stricture.

Distribution is more often segmental than diffuse. Pseu-dodiverticula may occur at, above, or below the level of a stricture.

Strictures associated with intramural pseudodiver-ticula should be evaluated carefully for evidence of malignancy.

Strictures associated with intramural pseudodiver-ticula should be evaluated carefully for evidence of malignancy.

SUGGESTED READING

Canon CL, Levine MS, Cherukuri R, et al. Intramural tracking: a feature of esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;175:371–374.

Levine MS, Moolten DN, Herlinger H, et al. Esophageal intramural pseudo-diverticulosis: a re-evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;147:1165–1170.

Luedtke P, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, et al. Radiologic diagnosis of benign esophageal strictures: a pattern approach. Radiographics 2003;23:897–909.

Plavsic BN, Chen MYM, Gelfand DW, et al. Intramural pseudodiverticulosis of the esophagus detected on barium esophagograms: increased prevalence in patients with esophageal carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;165:1381–1385.

ERIK K. PAULSON

HISTORY

A 57-year-old man presents with a long history of heartburn and gradual onset of dysphagia.

FIGURE 3-3A Barium swallow, single-contrast view. There is a smooth stricture in the mid esophagus with a small ulcer crater filled with barium.

FIGURE 3-3A Barium swallow, single-contrast view. There is a smooth stricture in the mid esophagus with a small ulcer crater filled with barium.

FIGURE 3-3B Barium swallow, double-contrast view, shows smooth mucosa within the stricture.

FIGURE 3-3B Barium swallow, double-contrast view, shows smooth mucosa within the stricture.

Peptic stricture: Peptic strictures are nearly always located in the distal esophagus, making this diagnosis unlikely. There is, however, an overlap in the appearance of peptic strictures and Barrett’s esophagus.

Peptic stricture: Peptic strictures are nearly always located in the distal esophagus, making this diagnosis unlikely. There is, however, an overlap in the appearance of peptic strictures and Barrett’s esophagus.

Caustic ingestion: A caustic stricture could have this appearance. In this scenario, clinical history would be the key to the diagnosis.

Caustic ingestion: A caustic stricture could have this appearance. In this scenario, clinical history would be the key to the diagnosis.

Mediastinal radiation: While radiation strictures may be long and smooth, as in this case, clinical history and port-limited changes should be apparent in the mediastinum and pulmonary parenchyma. With radiation strictures, there is often displacement of both walls of the esophagus.

Mediastinal radiation: While radiation strictures may be long and smooth, as in this case, clinical history and port-limited changes should be apparent in the mediastinum and pulmonary parenchyma. With radiation strictures, there is often displacement of both walls of the esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus: This is the most likely diagnosis given the ulcer, the length of the stricture, and the mid-esophageal location.

Barrett’s esophagus: This is the most likely diagnosis given the ulcer, the length of the stricture, and the mid-esophageal location.

Esophageal carcinoma: It is uncommon for esophageal carcinoma to present with a smooth stricture.

Esophageal carcinoma: It is uncommon for esophageal carcinoma to present with a smooth stricture.

DIAGNOSIS

Barrett’s esophagus with a stricture and ulcer

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Barrett’s esophagus represents columnar metaplasia of the squamous mucosa of the esophagus, associated with gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis.

Barrett’s esophagus represents columnar metaplasia of the squamous mucosa of the esophagus, associated with gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis.

Barrett’s is a premalignant condition, placing the patient at risk for esophageal carcinoma. Prevalence of adeno-carcinoma in this population is approximately 15%.

Barrett’s is a premalignant condition, placing the patient at risk for esophageal carcinoma. Prevalence of adeno-carcinoma in this population is approximately 15%.

Of patients with Barrett’s esophagus, 20% to 40% are asymptomatic.

Of patients with Barrett’s esophagus, 20% to 40% are asymptomatic.

Approximately 10% of patients with chronic reflux esophagitis also have Barrett’s esophagus.

Approximately 10% of patients with chronic reflux esophagitis also have Barrett’s esophagus.

Radiologic

The classic findings of Barrett’s esophagus include a high esophageal stricture with or without an associated ulcer. However, the classic findings are relatively uncommon. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus may have an unremarkable esophagram or may have a stricture in the distal esophagus, giving the appearance of a peptic stricture.

The classic findings of Barrett’s esophagus include a high esophageal stricture with or without an associated ulcer. However, the classic findings are relatively uncommon. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus may have an unremarkable esophagram or may have a stricture in the distal esophagus, giving the appearance of a peptic stricture.

As in this case, the stricture may be long and smooth or web-like.

As in this case, the stricture may be long and smooth or web-like.

On double-contrast esophagography, a reticular pattern may be present in the region of the columnar metaplasia that may resemble the area gastricae pattern found in the stomach.

On double-contrast esophagography, a reticular pattern may be present in the region of the columnar metaplasia that may resemble the area gastricae pattern found in the stomach.

Radiographic findings are neither sensitive nor specific for this condition. Therefore, endoscopy and biopsy are the procedures of choice to diagnose and follow these patients.

Radiographic findings are neither sensitive nor specific for this condition. Therefore, endoscopy and biopsy are the procedures of choice to diagnose and follow these patients.

SUGGESTED READING

Levine MS. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. In RM Gore, MS Levine, I Laufer (eds), Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1994;360–384.

Levine MS, Caroline DF, Thompson JJ, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus: relationship to Barrett mucosa. Radiology 1984;150:305–309.

Levine MS, Kressel HY, Caroline DF, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: reticular pattern of the mucosa. Radiology 1983;147:663–667.

Levine MS, Herman JB, Furth EE. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: the scope of the problem. Abdom Imaging 1995;20: 291–298.

Yamamoto AJ, Levine MS, Katzka DA, et al. Short-segment Barrett’s esophagus: findings on double-contrast esophagography in 20 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:1173–1178.

JEFFREY T.

SEABOURN

HISTORY

A 22-year-old woman presents with a several-month history of dysphagia and a 25-pound weight loss.

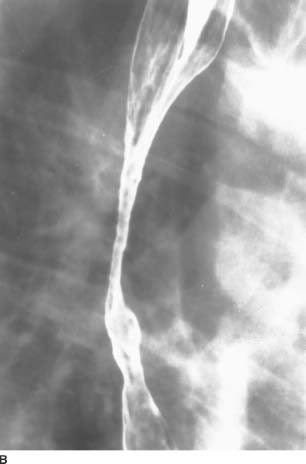

FIGURE 3-4A Chest CT (lung window) at the level of the gastroesophageal junction. There is marked dilatation of the distal esophagus with an air-fluid level. Neither mural thickening nor a mass at the gastroesophageal junction is present. The lung bases are normal.

FIGURE 3-4A Chest CT (lung window) at the level of the gastroesophageal junction. There is marked dilatation of the distal esophagus with an air-fluid level. Neither mural thickening nor a mass at the gastroesophageal junction is present. The lung bases are normal.

FIGURE 3-4B Barium swallow, single-contrast view. The esophagus is dilated, with smoothly marginated tapering at the gas-troesophageal junction. Mucous and debris remain in the proximal esophagus. Primary peristaltic activity was absent fluoroscopically.

FIGURE 3-4B Barium swallow, single-contrast view. The esophagus is dilated, with smoothly marginated tapering at the gas-troesophageal junction. Mucous and debris remain in the proximal esophagus. Primary peristaltic activity was absent fluoroscopically.

Peptic stricture: Although peptic strictures typically cause narrowing of the distal esophagus, they are usually smoothly marginated and relatively fixed.

Peptic stricture: Although peptic strictures typically cause narrowing of the distal esophagus, they are usually smoothly marginated and relatively fixed.

Primary achalasia: Lack of primary peristaltic activity with smooth tapering at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction and intermittent opening of the lower esopha-geal sphincter (LES) argue for a primary motor disorder of the esophagus. The age of the patient and lack of an obstructing or infiltrating mass favors primary achalasia.

Primary achalasia: Lack of primary peristaltic activity with smooth tapering at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction and intermittent opening of the lower esopha-geal sphincter (LES) argue for a primary motor disorder of the esophagus. The age of the patient and lack of an obstructing or infiltrating mass favors primary achalasia.

Secondary achalasia due to an intrinsic or extrinsic neoplasm: The age of the patient, duration of symptoms, and lack of a mass on imaging studies rules this entity out.

Secondary achalasia due to an intrinsic or extrinsic neoplasm: The age of the patient, duration of symptoms, and lack of a mass on imaging studies rules this entity out.

Complicated scleroderma: Narrowing of the distal esophagus in complicated scleroderma is the result of a patulous LES with free GE reflux, eventually causing a peptic stricture. The chest CT usually reveals normal lung bases.

Complicated scleroderma: Narrowing of the distal esophagus in complicated scleroderma is the result of a patulous LES with free GE reflux, eventually causing a peptic stricture. The chest CT usually reveals normal lung bases.

Chagas disease: This protozoal infection, which involves the myenteric plexus, results in a motor disorder of the esophagus similar to achalasia.

Chagas disease: This protozoal infection, which involves the myenteric plexus, results in a motor disorder of the esophagus similar to achalasia.

DIAGNOSIS

Primary achalasia

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Achalasia is a primary motility disorder of the esophagus characterized by aperistalsis in the distal two-thirds of the esophagus and failure of the LES to relax.

Achalasia is a primary motility disorder of the esophagus characterized by aperistalsis in the distal two-thirds of the esophagus and failure of the LES to relax.

The etiology is unknown, but it is thought to be neurogenic in origin. Pathologic specimens reveal a decrease in the number of ganglion cells in Auerbach’s myenteric plexus.

The etiology is unknown, but it is thought to be neurogenic in origin. Pathologic specimens reveal a decrease in the number of ganglion cells in Auerbach’s myenteric plexus.

Primary achalasia results in a slowly progressive dysphagia with both solids and liquids that may develop over many months or years. The patient may be able to modify dietary needs with smaller, frequent meals and, as a result, present without weight loss despite severe dysphagia.

Primary achalasia results in a slowly progressive dysphagia with both solids and liquids that may develop over many months or years. The patient may be able to modify dietary needs with smaller, frequent meals and, as a result, present without weight loss despite severe dysphagia.

Odynophagia and chest pain are much less common symptoms.

Odynophagia and chest pain are much less common symptoms.

Regurgitation may lead to choking and coughing and even to aspiration and pneumonitis.

Regurgitation may lead to choking and coughing and even to aspiration and pneumonitis.

Radiologic

Fluoroscopic examination of esophageal motility will identify characteristic absence of the primary peristaltic wave in the distal two-thirds of the esophagus.

Fluoroscopic examination of esophageal motility will identify characteristic absence of the primary peristaltic wave in the distal two-thirds of the esophagus.

The esophagus eventually dilates, with distal tapering (bird-beak or rat-tail appearance) at the GE junction.

The esophagus eventually dilates, with distal tapering (bird-beak or rat-tail appearance) at the GE junction.

An important cause of this radiologic appearance is pseudoachalasia due to malignancy. This typically occurs in an older age group (>50 years) with a shorter duration (<6 months) of dysphagia. This is most commonly due to a carcinoma of the gastric cardia or fun-dus with invasion of the distal esophagus. This may also be due to actual infiltration of the myenteric plexus or to high-grade obstruction at the GE junction.

An important cause of this radiologic appearance is pseudoachalasia due to malignancy. This typically occurs in an older age group (>50 years) with a shorter duration (<6 months) of dysphagia. This is most commonly due to a carcinoma of the gastric cardia or fun-dus with invasion of the distal esophagus. This may also be due to actual infiltration of the myenteric plexus or to high-grade obstruction at the GE junction.

SUGGESTED READING

Kahrilas PJ, Kishk SM, Helm JF, et al. Comparison of pseudoachalasia and achalasia. Am J Med 1987;82:439–446.

Laufer I. Motor disorders of the esophagus. In MS Levine (ed), Radiology of the Esophagus. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1989;229–246.

Liang CY, Lin MS. Images in clinical medicine. Achalasia. N Engl J Med 2009;360:801.

Pohl D, Tutuian R. Achalasia: an overview of diagnosis and treatment. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2007;16:297–303.

DAVID M. HOUGH

HISTORY

A 34-year-old man presents with crampy abdominal pain and diarrhea.

FIGURE 3-5 Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal series: spot film of the distal stomach and proximal duodenum. There is narrowing of the gastric antrum with multiple punctate collections of barium and surrounding halos of edema (aph-thous lesions). The duodenal bulb is not distended, and there are ulcerations in the bulb and second portion of the duodenum.

FIGURE 3-5 Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal series: spot film of the distal stomach and proximal duodenum. There is narrowing of the gastric antrum with multiple punctate collections of barium and surrounding halos of edema (aph-thous lesions). The duodenal bulb is not distended, and there are ulcerations in the bulb and second portion of the duodenum.

Erosive gastritis: Varioliform (meaning“resembling smallpox”) erosions may result from ingestion of alcohol, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Other causes include ischemia, stress, and trauma. Duodenal involvement would be unusual.

Erosive gastritis: Varioliform (meaning“resembling smallpox”) erosions may result from ingestion of alcohol, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Other causes include ischemia, stress, and trauma. Duodenal involvement would be unusual.

Infectious gastritis: Helicobacter pylori is an important cause of antral gastritis. Features include fold thickening, ulceration, and sometimes antral narrowing. There may also be duodenal ulceration. CMV infection occurs in AIDS and other immunocompromised patients. Nonspecific findings also include fold thickening, erosions or ulcers, and antral narrowing. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, herpes virus, toxoplasmosis, and crypto-sporidiosis may also have similar findings.

Infectious gastritis: Helicobacter pylori is an important cause of antral gastritis. Features include fold thickening, ulceration, and sometimes antral narrowing. There may also be duodenal ulceration. CMV infection occurs in AIDS and other immunocompromised patients. Nonspecific findings also include fold thickening, erosions or ulcers, and antral narrowing. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, herpes virus, toxoplasmosis, and crypto-sporidiosis may also have similar findings.

Granulomatous disease: Gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease typically has antral aphthous lesions, duodenal ulcers, and tapering of the antrum and pylorus, resulting in a“ram’s horn”configuration. Sarcoidosis, tuberculosis (TB), and syphilis may have similar features, with antral ulcers progressing to fibrosis and scarring.

Granulomatous disease: Gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease typically has antral aphthous lesions, duodenal ulcers, and tapering of the antrum and pylorus, resulting in a“ram’s horn”configuration. Sarcoidosis, tuberculosis (TB), and syphilis may have similar features, with antral ulcers progressing to fibrosis and scarring.

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES): Although the presence of postbulbar ulcers suggests ZES, there should also be gastric fold thickening and an increase in intra-luminal secretions and fluid.

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES): Although the presence of postbulbar ulcers suggests ZES, there should also be gastric fold thickening and an increase in intra-luminal secretions and fluid.

Eosinophilic gastritis: Although eosinophilic gastritis typically involves the gastric antrum and proximal small bowel, nodular fold thickening is a more common feature. Gastric erosions are atypical, and duodenal ulcers are rare.

Eosinophilic gastritis: Although eosinophilic gastritis typically involves the gastric antrum and proximal small bowel, nodular fold thickening is a more common feature. Gastric erosions are atypical, and duodenal ulcers are rare.

Scirrhous carcinoma: This entity typically causes a smooth, funnel-shaped narrowing of the antrum. Irregular fold thickening and ulceration may also occur. It is unlikely to cross the pylorus.

Scirrhous carcinoma: This entity typically causes a smooth, funnel-shaped narrowing of the antrum. Irregular fold thickening and ulceration may also occur. It is unlikely to cross the pylorus.

DIAGNOSIS

Gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Gastroduodenal Crohn’s is almost always associated with concomitant ileocecal disease but rarely may occur before the development of more distal disease.

Gastroduodenal Crohn’s is almost always associated with concomitant ileocecal disease but rarely may occur before the development of more distal disease.

Although it may be asymptomatic in the early stages, pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss are common in advanced stages. Gastric outlet obstruction may even occur.

Although it may be asymptomatic in the early stages, pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss are common in advanced stages. Gastric outlet obstruction may even occur.

Radiologic

Gastric Crohn’s disease typically involves the antrum and sometimes the body. Fundal involvement is uncommon. Duodenal disease usually occurs in association with antral involvement, but isolated duodenal disease is possible.

Gastric Crohn’s disease typically involves the antrum and sometimes the body. Fundal involvement is uncommon. Duodenal disease usually occurs in association with antral involvement, but isolated duodenal disease is possible.

Aphthous lesions may appear as punctate or slit-like collections of barium with a lucent halo, indistinguishable from varioliform ulcers of erosive gastritis. Larger ulcers, mucosal effacement, or cobblestoning may also occur.

Aphthous lesions may appear as punctate or slit-like collections of barium with a lucent halo, indistinguishable from varioliform ulcers of erosive gastritis. Larger ulcers, mucosal effacement, or cobblestoning may also occur.

Fibrosis may result in a funnel-shaped or“ram’s horn”antrum. A pseudo-Billroth I sign is due to scarring of the antrum and duodenum with obliteration of the pylorus.

Fibrosis may result in a funnel-shaped or“ram’s horn”antrum. A pseudo-Billroth I sign is due to scarring of the antrum and duodenum with obliteration of the pylorus.

Duodenal ulcers may be single or multiple. Duodenal strictures are usually postbulbar, smoothly tapering, and may be multiple. Skip lesions may occur.

Duodenal ulcers may be single or multiple. Duodenal strictures are usually postbulbar, smoothly tapering, and may be multiple. Skip lesions may occur.

Asymmetric or eccentric scarring in the duodenum may result in pseudodiverticula.

Asymmetric or eccentric scarring in the duodenum may result in pseudodiverticula.

SUGGESTED READING

Farman J, Faegenburg D, Dallemand S, et al. Crohn’s disease of the stomach: the“rams-horn”sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1975;123:242–251.

Levine M. Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Radiol Clin North Am 1987;25:79–91.

Nelson SW. Some interesting and unusual manifestations of Crohn’s disease of the stomach, duodenum and small intestine. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1969;107:86–101.

Hizawa K, Iida M, Kohrogi N, et al. Crohn disease: early recognition and progress of aphthous lesions. Radiology 1994;190:451–454.

Gore RM, Ghahremani GG. Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging 1986;25:305–331.

VINCENT H.S. LOW

HISTORY

A 40-year-old man presents with dyspepsia. He is taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents for arthritis.

FIGURE 3-6 Double-contrast upper examination: view of distal body and antrum of the stomach. Numerous dense specks are seen along the gastric antrum, predominantly toward the greater curvature. Some of these appear longitudinally oriented, and most demonstrate a lucent surrounding halo, representing edema.

FIGURE 3-6 Double-contrast upper examination: view of distal body and antrum of the stomach. Numerous dense specks are seen along the gastric antrum, predominantly toward the greater curvature. Some of these appear longitudinally oriented, and most demonstrate a lucent surrounding halo, representing edema.

Erosive gastritis: This is the most likely diagnosis given the history and linear distribution of lesions along the rugal folds.

Erosive gastritis: This is the most likely diagnosis given the history and linear distribution of lesions along the rugal folds.

Crohn’s disease: Gastric involvement usually occurs in the presence of advanced disease elsewhere, particularly the terminal ileum.

Crohn’s disease: Gastric involvement usually occurs in the presence of advanced disease elsewhere, particularly the terminal ileum.

Viral infection: This type of gastritis usually occurs in patients with immunodeficiency.

Viral infection: This type of gastritis usually occurs in patients with immunodeficiency.

Ulcerated submucosal masses: With these masses, the central ulcer, as well as the surrounding mass, tends to be larger than in this case.

Ulcerated submucosal masses: With these masses, the central ulcer, as well as the surrounding mass, tends to be larger than in this case.

Barium precipitates: These artifacts do not have a radiolucent halo and will move when the patient is repositioned, either by the effect of gravity or the flowing pool of liquid barium.

Barium precipitates: These artifacts do not have a radiolucent halo and will move when the patient is repositioned, either by the effect of gravity or the flowing pool of liquid barium.

DIAGNOSIS

Erosive gastritis

KEY FACTS

Clinical

These erosions are superficial epithelial defects that do not extend beyond the muscularis mucosa.

These erosions are superficial epithelial defects that do not extend beyond the muscularis mucosa.

Drugs are an identifiable cause of erosive gastritis, including aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, and alcohol.

Drugs are an identifiable cause of erosive gastritis, including aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, and alcohol.

In half the cases, no cause is identified. These cases are probably a manifestation of peptic disease.

In half the cases, no cause is identified. These cases are probably a manifestation of peptic disease.

Other causes of gastric erosions include Crohn’s disease, viral infection, and iatrogenic trauma (gastric catheters and endoscopic therapy).

Other causes of gastric erosions include Crohn’s disease, viral infection, and iatrogenic trauma (gastric catheters and endoscopic therapy).

Radiologic

Erosions appear as very shallow collections of barium. These are always small and may have a variety of shapes, including round, polygonal, linear, and punctate.

Erosions appear as very shallow collections of barium. These are always small and may have a variety of shapes, including round, polygonal, linear, and punctate.

There is associated nodular thickening of the rugal folds, and the erosions are aligned along the crest of these folds. On barium studies, the abnormal folds are often more easily visualized than the erosions themselves, and they may persist after the erosions have healed.

There is associated nodular thickening of the rugal folds, and the erosions are aligned along the crest of these folds. On barium studies, the abnormal folds are often more easily visualized than the erosions themselves, and they may persist after the erosions have healed.

Because the lesions are shallow, the changes are subtle. Disease on the more dependent posterior wall is visualized more readily by manipulating a thin film of barium into the region to opacify the erosions and the spaces between the folds. Disease on the anterior wall is visualized best in the prone position using compression.

Because the lesions are shallow, the changes are subtle. Disease on the more dependent posterior wall is visualized more readily by manipulating a thin film of barium into the region to opacify the erosions and the spaces between the folds. Disease on the anterior wall is visualized best in the prone position using compression.

SUGGESTED READING

Catalano D, Pagliari U. Gastroduodenal erosions: radiological findings. Gastrointest Radiol 1982;7:235–240.

Laufer I, Hamilton J, Mullens JE. Demonstration of superficial gastric erosions by double contrast radiography. Gastroenterology 1975;68:387–391.

Levine MS. Erosive gastritis and gastric ulcers. Radiol Clin North Am 1994;32:1203–1214.

Momoshima S, Imai Y, Sugino Y, et al. Radiologic findings of linear gastric erosions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;147:701–703.

VINCENT H.S.

LOW

HISTORY

A 50-year-old woman presents with epigastric pain for several months.

FIGURE 3-7A Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: view of the distal gastric antrum in the left posterior oblique position. There is elevation of the mucosa measuring 2.5 cm in diameter along the greater curvature, just proximal to the pylorus. A central small collection of barium is seen within this lesion. The margins of the lesion appear smooth.

FIGURE 3-7A Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: view of the distal gastric antrum in the left posterior oblique position. There is elevation of the mucosa measuring 2.5 cm in diameter along the greater curvature, just proximal to the pylorus. A central small collection of barium is seen within this lesion. The margins of the lesion appear smooth.

FIGURE 3-7B Right posterior oblique position view of the distal gastric antrum. Rotation of the patient into the right posterior oblique position brings the lesion into profile, further demonstrating the smooth outline of the lesion and the central (5-mm deep) niche of barium.

FIGURE 3-7B Right posterior oblique position view of the distal gastric antrum. Rotation of the patient into the right posterior oblique position brings the lesion into profile, further demonstrating the smooth outline of the lesion and the central (5-mm deep) niche of barium.

Gastric ulcer: An ulcer would have a central niche of barium and a surrounding mound of edema. However, such mounds usually have peripheral indistinct or fading borders, in contrast to the sharp outline of this lesion.

Gastric ulcer: An ulcer would have a central niche of barium and a surrounding mound of edema. However, such mounds usually have peripheral indistinct or fading borders, in contrast to the sharp outline of this lesion.

Leiomyoma: This uncommon benign tumor could have this appearance, as would other benign mesenchymal tumors.

Leiomyoma: This uncommon benign tumor could have this appearance, as would other benign mesenchymal tumors.

Ectopic pancreatic rest: This is the most likely diagnosis by virtue of its benign submucosal appearance with central umbilication, as well as its typical location in the distal antrum along the greater curvature.

Ectopic pancreatic rest: This is the most likely diagnosis by virtue of its benign submucosal appearance with central umbilication, as well as its typical location in the distal antrum along the greater curvature.

Bull’s-eye”metastases: These can appear with metastatic melanoma, lymphoma, or Kaposi’s sarcoma. However, they are almost always multiple and occur in the context of disseminated disease elsewhere.

Bull’s-eye”metastases: These can appear with metastatic melanoma, lymphoma, or Kaposi’s sarcoma. However, they are almost always multiple and occur in the context of disseminated disease elsewhere.

DIAGNOSIS

Ectopic pancreatic rest

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Ectopic pancreas occurs due to an anomaly in embryo-logic development, where a fragment of migrating pancreatic precursor becomes implanted in the intestinal wall. Histologically, all normal pancreatic elements are present but show a disorganized arrangement.

Ectopic pancreas occurs due to an anomaly in embryo-logic development, where a fragment of migrating pancreatic precursor becomes implanted in the intestinal wall. Histologically, all normal pancreatic elements are present but show a disorganized arrangement.

The majority of pancreatic rests occur in the stomach (80%). They are also found in the duodenum and proximal jejunum. They have also been reported in the gallbladder, bile ducts, liver, spleen, appendix, Meckel’s diverticulum, omentum, mesentery, and mediastinum.

The majority of pancreatic rests occur in the stomach (80%). They are also found in the duodenum and proximal jejunum. They have also been reported in the gallbladder, bile ducts, liver, spleen, appendix, Meckel’s diverticulum, omentum, mesentery, and mediastinum.

These lesions are usually asymptomatic and discovery of such should not be accepted as the cause of a patient’s symptoms.

These lesions are usually asymptomatic and discovery of such should not be accepted as the cause of a patient’s symptoms.

Rarely, enzyme production results in epigastric pain and intestinal bleeding. These lesions have also been reported to cause gastric outlet obstruction due to their strategic position near the pylorus.

Rarely, enzyme production results in epigastric pain and intestinal bleeding. These lesions have also been reported to cause gastric outlet obstruction due to their strategic position near the pylorus.

Radiologic

The lesion appears as a smooth, broad-based, solitary, submucosal mass.

The lesion appears as a smooth, broad-based, solitary, submucosal mass.

The most common location is along the distal greater curvature of the stomach, several centimeters from the pylorus.

The most common location is along the distal greater curvature of the stomach, several centimeters from the pylorus.

The central umbilication or dimple is thought to represent the orifice of the duct in this rest. It usually measures 1 to 5 mm in diameter and 5 to 10 mm in depth. Rarely, a rudimentary ductal system may fill with contrast material.

The central umbilication or dimple is thought to represent the orifice of the duct in this rest. It usually measures 1 to 5 mm in diameter and 5 to 10 mm in depth. Rarely, a rudimentary ductal system may fill with contrast material.

SUGGESTED READING

Kim JY, Lee JM, Kim KW, et al. Ectopic pancreas: CT findings with emphasis on differentiation from small gastrointestinal stromal tumor and leiomyoma. Radiology 2009;252:92–100.

Levine MS. Benign tumors of the stomach and duodenum. In RM Gore, MS Levine, I Laufer (eds), Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1994:649–651.

Rubesin SE, Furth EE, Birnbaum BA, et al. Ectopic pancreas complicated by pancreatitis and pseudocyst formation mimicking jejunal diverticulitis. Br J Radiol 1997;70:311–313.

Thoeni RF, Gedgaudas RK. Ectopic pancreas: usual and unusual features. Gastrointest Radiol 1980;5:37–42.

JEFFREY T.

SEABOURN

HISTORY

A 44-year-old woman with stage IV breast carcinoma is status post bone marrow transplant and high-dose chemotherapy.

FIGURE 3-8A CT of the upper abdomen at the level of the celiac axis following intravenous contrast material. The wall of the stomach is diffusely thickened. Enlarged lymph nodes are also noted along the gastrohepatic ligament. There is an incidental cyst in the left hepatic lobe.

FIGURE 3-8A CT of the upper abdomen at the level of the celiac axis following intravenous contrast material. The wall of the stomach is diffusely thickened. Enlarged lymph nodes are also noted along the gastrohepatic ligament. There is an incidental cyst in the left hepatic lobe.

FIGURE 3-8B CT of the upper abdomen at a lower level reveals diffuse thickening of the gastric antrum.

FIGURE 3-8B CT of the upper abdomen at a lower level reveals diffuse thickening of the gastric antrum.

Diffusely infiltrating (scirrhous) adenocarcinoma of the stomach: The appearance of diffuse gastric wall thickening in a poorly distensible stomach is radio-graphically indistinguishable from diffusely infiltrating metastatic disease.

Diffusely infiltrating (scirrhous) adenocarcinoma of the stomach: The appearance of diffuse gastric wall thickening in a poorly distensible stomach is radio-graphically indistinguishable from diffusely infiltrating metastatic disease.

Diffusely infiltrating metastatic disease: Given the patient’s clinical history, this is the most likely diagnosis.

Diffusely infiltrating metastatic disease: Given the patient’s clinical history, this is the most likely diagnosis.

Lymphoma: Diffuse gastric involvement with lym-phoma may give this appearance. While there are enlarged lymph nodes along the gastrohepatic ligament in this patient, there is no retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. The spleen is normal in size. When there is gastric involvement of lymphoma, it may cross the pylorus to involve the duodenum. The duodenum is normal in this patient.

Lymphoma: Diffuse gastric involvement with lym-phoma may give this appearance. While there are enlarged lymph nodes along the gastrohepatic ligament in this patient, there is no retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. The spleen is normal in size. When there is gastric involvement of lymphoma, it may cross the pylorus to involve the duodenum. The duodenum is normal in this patient.

Infectious/inflammatory gastritis: Crohn’s disease, chronic gastric ulcer disease with spasm, eosinophilic gastritis, sarcoidosis, TB, and brucellosis are other causes of gastric wall thickening and luminal narrowing. These more typically involve the gastric antrum.

Infectious/inflammatory gastritis: Crohn’s disease, chronic gastric ulcer disease with spasm, eosinophilic gastritis, sarcoidosis, TB, and brucellosis are other causes of gastric wall thickening and luminal narrowing. These more typically involve the gastric antrum.

Physical/chemical gastritis: Corrosive gastritis, post-radiation injury, and hepatic arterial chemotherapy infusion are other less common causes of this appearance.

Physical/chemical gastritis: Corrosive gastritis, post-radiation injury, and hepatic arterial chemotherapy infusion are other less common causes of this appearance.

DIAGNOSIS

Diffusely infiltrating metastatic breast carcinoma to the stomach (linitis plastica appearance)

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Metastatic disease to the stomach is not uncommon. The most common organs of origin include malignant melanoma, breast, lung, colon, prostate, leukemia, and secondary lymphoma.

Metastatic disease to the stomach is not uncommon. The most common organs of origin include malignant melanoma, breast, lung, colon, prostate, leukemia, and secondary lymphoma.

The pattern of gastric involvement is variable. Solitary mass: 50%; multiple nodules: 30%; and linitis plastica (diffusely infiltrating): 20%. The diffusely infiltrating variety is most commonly seen in breast carcinoma.

The pattern of gastric involvement is variable. Solitary mass: 50%; multiple nodules: 30%; and linitis plastica (diffusely infiltrating): 20%. The diffusely infiltrating variety is most commonly seen in breast carcinoma.

Patients often present with early satiety, nausea, and vomiting. This patient could not tolerate oral contrast material due to severe nausea and vomiting.

Patients often present with early satiety, nausea, and vomiting. This patient could not tolerate oral contrast material due to severe nausea and vomiting.

Radiologic

The differential diagnosis for diffuse gastric wall thickening with a poorly distensible lumen is fairly extensive. Malignant causes head the list and are most commonly due to the diffusely infiltrating variety of adenocarcinoma of the stomach, metastatic disease, or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The differential diagnosis for diffuse gastric wall thickening with a poorly distensible lumen is fairly extensive. Malignant causes head the list and are most commonly due to the diffusely infiltrating variety of adenocarcinoma of the stomach, metastatic disease, or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Other causes of this radiographic appearance include inflammation secondary to chronic gastritis, Crohn’s disease giving a pseudo-Billroth I appearance, eosino-philic gastritis, and sarcoidosis.

Other causes of this radiographic appearance include inflammation secondary to chronic gastritis, Crohn’s disease giving a pseudo-Billroth I appearance, eosino-philic gastritis, and sarcoidosis.

Infectious etiologies include TB and brucellosis. TB may be radiographically indistinguishable from Crohn’s disease as a cause of antral narrowing.

Infectious etiologies include TB and brucellosis. TB may be radiographically indistinguishable from Crohn’s disease as a cause of antral narrowing.

Physical/chemical causes are most commonly due to corrosive gastritis and radiation therapy.

Physical/chemical causes are most commonly due to corrosive gastritis and radiation therapy.

SUGGESTED READING

Eisenberg RL. Gastrointestinal Radiology: a Pattern Approach (2nd ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1990;205–222.

Elliott LA, Hall GD, Perren TJ, Spencer JA. Metastatic breast carcinoma involving the gastric antrum and duodenum: computed tomography appearances. Br J Radiol 1995;68:970–972.

Jaffe M. Metastatic involvement of the stomach secondary to breast carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1975;123:512–521.

Karadeniz-Bilgili MY, Hyslop B, Pamuklar E, et al. MRI findings of gastric metastases from breast carcinoma. Magn Reson Imaging 2005;23:115–118.

Levine MS, Kong V, Rubesin SE, et al. Scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach: radiologic and endoscopic diagnosis. Radiology 1990;175:151–154.

Levine MS, Megibow AJ. Stomach and duodenum: carcinoma. In RM Gore, MS Levine, I Laufer (eds), Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology (vol.1). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1994;660–683.

Winston CB, Hadar O, Teitcher JB, et al. Metastatic lobular carcinoma of the breast: patterns of spread in the chest, abdomen, and pelvis on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;175:795–800.

DAVID M. HOUGH

HISTORY

A 38-year-old woman presents with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Her serum amylase and lipase levels were elevated.

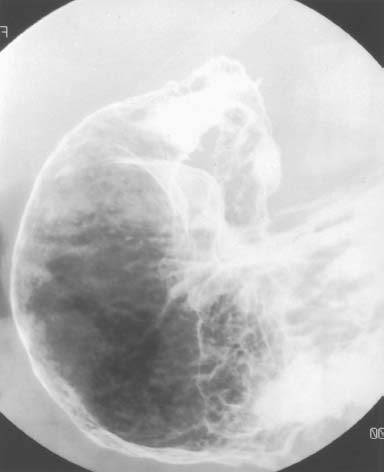

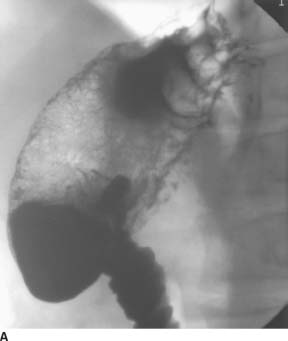

FIGURE 3-9A Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: spot film of the stomach and duodenum. There is lobulated fold thickening in the gastric fundus.

FIGURE 3-9A Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: spot film of the stomach and duodenum. There is lobulated fold thickening in the gastric fundus.

FIGURE 3-9B Spot film of the gastric fundus from the same examination. Gastric fold thickening is again seen, although the mucosa appears intact. The esophagus (not shown) was normal in appearance.

FIGURE 3-9B Spot film of the gastric fundus from the same examination. Gastric fold thickening is again seen, although the mucosa appears intact. The esophagus (not shown) was normal in appearance.

Hypertrophic gastritis: This is a condition characterized by glandular hyperplasia and increased acid secretion, with thickened folds predominantly in the fundus and body of the stomach. The majority of cases have an associated peptic ulcer. The focal nature of fold thickening in this case makes the diagnosis unlikely.

Hypertrophic gastritis: This is a condition characterized by glandular hyperplasia and increased acid secretion, with thickened folds predominantly in the fundus and body of the stomach. The majority of cases have an associated peptic ulcer. The focal nature of fold thickening in this case makes the diagnosis unlikely.

Ménétriers disease: The gastric folds are usually more thickened than in hypertrophic gastritis, and there is relative sparing of the antrum. There may be mass-like fold thickening, although the abnormality is unlikely to be as focal as in this case. The folds in Menetriers disease also tend to follow the distribution of normal rugae, and there are increased secretions.

Ménétriers disease: The gastric folds are usually more thickened than in hypertrophic gastritis, and there is relative sparing of the antrum. There may be mass-like fold thickening, although the abnormality is unlikely to be as focal as in this case. The folds in Menetriers disease also tend to follow the distribution of normal rugae, and there are increased secretions.

Lymphoma: Gastric lymphoma may cause irregular or lobulated fold thickening due to submucosal infiltration or multiple submucosal masses. Submucosal infiltration by carcinoma may also cause this appearance.

Lymphoma: Gastric lymphoma may cause irregular or lobulated fold thickening due to submucosal infiltration or multiple submucosal masses. Submucosal infiltration by carcinoma may also cause this appearance.

Varices: Gastric varices typically appear as multiple, smooth, lobulated, filling defects that tend to change in size and shape on fluoroscopy. The serpentine appearance of the folds in this case favors this diagnosis.

Varices: Gastric varices typically appear as multiple, smooth, lobulated, filling defects that tend to change in size and shape on fluoroscopy. The serpentine appearance of the folds in this case favors this diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

Isolated gastric varices

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Gastric varices are less likely to bleed than esophageal varices. However, they may present with low-grade bleeding or massive hematemesis.

Gastric varices are less likely to bleed than esophageal varices. However, they may present with low-grade bleeding or massive hematemesis.

Gastric varices are usually associated with esopha-geal varices and are secondary to cirrhosis with portal hypertension.

Gastric varices are usually associated with esopha-geal varices and are secondary to cirrhosis with portal hypertension.

Isolated gastric varices may be caused by splenic vein thrombosis, resulting in shunting of blood from the spleen through the short gastric veins to the fundus, where they anastomose with branches of the coronary vein and esophageal plexus. With normal portal venous pressure, the blood can drain via the coronary vein into the portal vein without producing esophageal varices.

Isolated gastric varices may be caused by splenic vein thrombosis, resulting in shunting of blood from the spleen through the short gastric veins to the fundus, where they anastomose with branches of the coronary vein and esophageal plexus. With normal portal venous pressure, the blood can drain via the coronary vein into the portal vein without producing esophageal varices.

Radiologic

Gastric varices are characteristically multiple, lobulated, serpentine masses, but they may produce a single polypoid mass in the fundus.

Gastric varices are characteristically multiple, lobulated, serpentine masses, but they may produce a single polypoid mass in the fundus.

Gastric varices may be obscured on barium studies by the normal overlying gastric rugae. Gastric varices are seen radiographically in <50% of patients with uphill esophageal varices.

Gastric varices may be obscured on barium studies by the normal overlying gastric rugae. Gastric varices are seen radiographically in <50% of patients with uphill esophageal varices.

It is important to examine the distal esophagus in patients with gastric varices in order to identify esopha-geal varices.

It is important to examine the distal esophagus in patients with gastric varices in order to identify esopha-geal varices.

A double-contrast barium technique is considered more reliable than a single-contrast technique for identification of varices.

A double-contrast barium technique is considered more reliable than a single-contrast technique for identification of varices.

The isolated gastric varices in this patient were due to splenic vein occlusion secondary to pancreatitis. Because portal hypertension is much more common than splenic vein occlusion, most patients with isolated gastric varices are found to have portal hypertension as the underlying cause.

The isolated gastric varices in this patient were due to splenic vein occlusion secondary to pancreatitis. Because portal hypertension is much more common than splenic vein occlusion, most patients with isolated gastric varices are found to have portal hypertension as the underlying cause.

SUGGESTED READING

Evans JA, Delany F. Gastric varices. Radiology 1953;60:46–51.

Levine MS, Kieu K, Rubesin SE, et al. Isolated gastric varices: splenic vein obstruction or portal hypertension? Gastrointest Radiol 1990;15:188–192.

Kim SH, Kim YJ, Lee JM, et al. Esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: multidetector CT esophagography-comparison with endoscopy. Radiology 2007;242:759–768.

Kim YJ, Raman SS, Yu NC, et al. Esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients: evaluation with liver CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:139–144.

Muhletaler C, Gerlock J, Goncharenko V, et al. Gastric varices secondary to splenic vein occlusion: radiographic diagnosis and clinical significance. Radiology 1979;132:593–598.

VINCENT H.S.

LOW

HISTORY

A 33-year-old man presents with dyspepsia. He has had many hospital admissions since childhood for recurrent pulmonary infections.

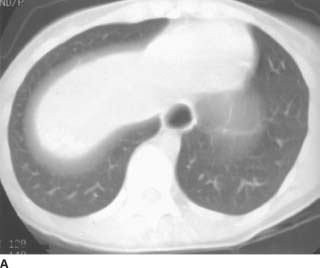

FIGURE 3-10A Full-column, single-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: view of the duodenum. There are nodular indentations in the duodenal walls.

FIGURE 3-10A Full-column, single-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: view of the duodenum. There are nodular indentations in the duodenal walls.

FIGURE 3-10B Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: view of the duodenum. The duodenal folds appear flattened, smudged, and poorly defined.

FIGURE 3-10B Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium examination: view of the duodenum. The duodenal folds appear flattened, smudged, and poorly defined.

FIGURE 3-10C Frontal chest radiograph. There is fibrosis and bronchiectasis with a predominant upper lobe distribution.

FIGURE 3-10C Frontal chest radiograph. There is fibrosis and bronchiectasis with a predominant upper lobe distribution.

FIGURE 3-10D Contrast-enhanced CT of the upper abdomen. The pancreatic parenchyma has been replaced completely by fat.

FIGURE 3-10D Contrast-enhanced CT of the upper abdomen. The pancreatic parenchyma has been replaced completely by fat.

Peptic duodenitis: This is a common condition that may coexist with other pathologic conditions that cause pulmonary abnormalities. Alternatively, the duodenitis may have been caused by steroids or other medications used to treat the lung condition. They do not explain the pancreatic findings.

Peptic duodenitis: This is a common condition that may coexist with other pathologic conditions that cause pulmonary abnormalities. Alternatively, the duodenitis may have been caused by steroids or other medications used to treat the lung condition. They do not explain the pancreatic findings.

Cystic fibrosis: This is the most likely diagnosis as it would explain both the pulmonary, duodenal, and pancreatic findings. The patient’s age, however, is rather advanced for this condition.

Cystic fibrosis: This is the most likely diagnosis as it would explain both the pulmonary, duodenal, and pancreatic findings. The patient’s age, however, is rather advanced for this condition.

Scleroderma: Intestinal fibrosis from scleroderma may produce this duodenal pattern and may also be associated with pulmonary fibrosis.

Scleroderma: Intestinal fibrosis from scleroderma may produce this duodenal pattern and may also be associated with pulmonary fibrosis.

Tuberculosis (TB): TB would explain the upper lobe fibrotic changes. Duodenal involvement, however, is rare and usually results in strictures and fistulae.

Tuberculosis (TB): TB would explain the upper lobe fibrotic changes. Duodenal involvement, however, is rare and usually results in strictures and fistulae.

Pancreatitis and other periduodenal inflammatory processes: These conditions may cause the nonspecific duodenal changes as well as pancreatic atrophy but do not adequately explain the pulmonary abnormalities.

Pancreatitis and other periduodenal inflammatory processes: These conditions may cause the nonspecific duodenal changes as well as pancreatic atrophy but do not adequately explain the pulmonary abnormalities.

DIAGNOSIS

Cystic fibrosis

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Cystic fibrosis occurs in 1 in 2,000 births, predominantly in whites. Clinical and radiologic manifestations occur due to viscous secretions.

Cystic fibrosis occurs in 1 in 2,000 births, predominantly in whites. Clinical and radiologic manifestations occur due to viscous secretions.

The diagnosis is usually made clinically in infancy, but in about 2% of patients, symptoms may not manifest until after 18 years of age. Older patients typically present with hepatobiliary or gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

The diagnosis is usually made clinically in infancy, but in about 2% of patients, symptoms may not manifest until after 18 years of age. Older patients typically present with hepatobiliary or gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

With improvements in pulmonary care, increasing numbers of cystic fibrosis patients are surviving into adulthood.

With improvements in pulmonary care, increasing numbers of cystic fibrosis patients are surviving into adulthood.

A majority (85%) of patients will have malabsorption due to impaired exocrine pancreatic secretions. These secretions are viscous, low in bicarbonates, and low in enzymes.

A majority (85%) of patients will have malabsorption due to impaired exocrine pancreatic secretions. These secretions are viscous, low in bicarbonates, and low in enzymes.

Radiologic

Duodenal changes are seen in 60% to 80% of patients and consist of fold thickening, mucosal nodularity, fold flattening, luminal dilatation, smudging, and poor definition of the mucosal fold pattern. These changes are usually confined to the first and second portions of the duodenum and occur without ulcerations.

Duodenal changes are seen in 60% to 80% of patients and consist of fold thickening, mucosal nodularity, fold flattening, luminal dilatation, smudging, and poor definition of the mucosal fold pattern. These changes are usually confined to the first and second portions of the duodenum and occur without ulcerations.

In the small bowel, blobs of mucous result in a network pattern of curved lines, predominantly involving the distal small bowel.

In the small bowel, blobs of mucous result in a network pattern of curved lines, predominantly involving the distal small bowel.

Intestinal obstruction and impaction can occur during and after childhood.

Intestinal obstruction and impaction can occur during and after childhood.

Pancreatic calcification may be evident on plain radiographs. Profound fatty replacement of the pancreas is often seen on CT or MR. Beaded dilatation of the main pancreatic duct may also be seen as can intrapancre-atic cysts, likely representing markedly dilated side branches.

Pancreatic calcification may be evident on plain radiographs. Profound fatty replacement of the pancreas is often seen on CT or MR. Beaded dilatation of the main pancreatic duct may also be seen as can intrapancre-atic cysts, likely representing markedly dilated side branches.

SUGGESTED READING

Nijs EL, Callahan MJ. Congenital and developmental pancreatic anomalies: ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging features. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2007;28:395–401.

Phelan MS, Fine DR, Zentler-Munro L, et al. Radiographic abnormalities of the duodenum in cystic fibrosis. Clin Radiol 1983;34:573–577.

Robertson MB, Choe KA, Joseph PM. Review of the abdominal manifestations of cystic fibrosis in the adult patient. Radiographics 2006;26:679–690.

Saavedra MT, Lynch DA. Emerging roles for CT imaging in cystic fibrosis. Radiology 2009;252:327–329.

Taussig LM, Saldino RM, di Sant’Agnese PA. Radiographic abnormalities of the duodenum and small bowel in cystic fibrosis of the pancreas (mucoviscidosis). Pediatr Radiol 1973;106:369–376.

KELLY S. FREED

HISTORY

A 35-year-old man presents with a 6-month history of diarrhea.

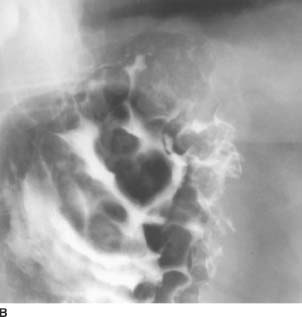

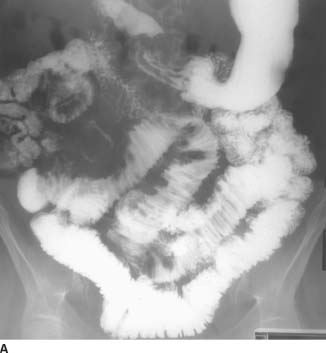

FIGURE 3-11A Small-bowel follow-through barium examination: spot film of the terminal ileum. The terminal ileum demonstrates luminal narrowing, known as the“string sign.”There is also involvement of an adjacent loop of ileum. The intervening section of small bowel, which is relatively dilated, is less involved by the disease process. Linear ulceration is seen along the mesenteric border of the terminal ileum. At least two fistulae are seen along the antimesenteric border.

FIGURE 3-11A Small-bowel follow-through barium examination: spot film of the terminal ileum. The terminal ileum demonstrates luminal narrowing, known as the“string sign.”There is also involvement of an adjacent loop of ileum. The intervening section of small bowel, which is relatively dilated, is less involved by the disease process. Linear ulceration is seen along the mesenteric border of the terminal ileum. At least two fistulae are seen along the antimesenteric border.

FIGURE 3-11B CT scan of the pelvis following intravenous and oral contrast material. The terminal ileum and cecum demonstrate bowel wall thickening with inflammatory change in the adjacent mesenteric fat.

FIGURE 3-11B CT scan of the pelvis following intravenous and oral contrast material. The terminal ileum and cecum demonstrate bowel wall thickening with inflammatory change in the adjacent mesenteric fat.

Crohn’s disease: Involvement of the distal and terminal ileum, discontinuous segments of disease, as well as stricture and/or fistulae formation are characteristic of Crohn’s disease. The CT appearance is also typical, with the marked mural thickening and inflammatory change in the mesenteric fat.

Crohn’s disease: Involvement of the distal and terminal ileum, discontinuous segments of disease, as well as stricture and/or fistulae formation are characteristic of Crohn’s disease. The CT appearance is also typical, with the marked mural thickening and inflammatory change in the mesenteric fat.

Ulcerative colitis: Ulcerative colitis can involve the terminal ileum by backwash ileitis, but the discontinuous involvement makes this diagnosis less likely. Additionally, the fistula formation and inflammatory change in the adjacent mesenteric fat are unusual.

Ulcerative colitis: Ulcerative colitis can involve the terminal ileum by backwash ileitis, but the discontinuous involvement makes this diagnosis less likely. Additionally, the fistula formation and inflammatory change in the adjacent mesenteric fat are unusual.

Ischemia: The distribution of disease makes a vascular etiology lower in the differential diagnosis. An ischemic insult to bowel more commonly involves the left than the right colon, and small bowel involvement is less common.

Ischemia: The distribution of disease makes a vascular etiology lower in the differential diagnosis. An ischemic insult to bowel more commonly involves the left than the right colon, and small bowel involvement is less common.

Neoplasms: Adenocarcinoma more commonly involves the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum. Lymphoma usually presents as polypoid masses or large ulcerative/ excavating lesions.

Neoplasms: Adenocarcinoma more commonly involves the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum. Lymphoma usually presents as polypoid masses or large ulcerative/ excavating lesions.

Infection: TB is rare in developed countries. Features that suggest TB rather than Crohn’s disease include greater involvement of the cecum than the terminal ileum and the fact that ulcers tend to be larger with TB. Yersinia ileitis may also have an appearance similar to Crohn’s disease, but the disease is self-limited and the radiographic changes would return to normal in time.

Infection: TB is rare in developed countries. Features that suggest TB rather than Crohn’s disease include greater involvement of the cecum than the terminal ileum and the fact that ulcers tend to be larger with TB. Yersinia ileitis may also have an appearance similar to Crohn’s disease, but the disease is self-limited and the radiographic changes would return to normal in time.

Other perienteric inflammatory conditions: Appendicitis or endometriosis are included in the differential diagnosis. The involvement of a loop of distal ileum in addition to the cecum and terminal ileum makes appendicitis less likely. Endometriosis may cause serosal abnormalities on the bowel, but not the strictures and fistulas seen in this patient. Additionally, endometriosis more commonly affects the sigmoid and transverse mesocolon.

Other perienteric inflammatory conditions: Appendicitis or endometriosis are included in the differential diagnosis. The involvement of a loop of distal ileum in addition to the cecum and terminal ileum makes appendicitis less likely. Endometriosis may cause serosal abnormalities on the bowel, but not the strictures and fistulas seen in this patient. Additionally, endometriosis more commonly affects the sigmoid and transverse mesocolon.

DIAGNOSIS

Crohn’s disease

KEY FACTS

Clinical

Crohn’s disease is an inflammatory bowel disease of unknown etiology. There is a family history in approximately 40% of cases. The overall incidence is approximately 5 in 100,000. The age of onset is usually in adolescence or young adulthood.

Crohn’s disease is an inflammatory bowel disease of unknown etiology. There is a family history in approximately 40% of cases. The overall incidence is approximately 5 in 100,000. The age of onset is usually in adolescence or young adulthood.

Early Crohn’s disease is a mucosal disorder characterized by aphthous lesions, which can be detected by a double contrast barium examination or endoscopy. The disease progresses to the submucosa and eventually becomes transmural. Any portion of the gastrointestinal tract can be involved, although the terminal ileum is the most common site of disease. Extraintestinal involvement includes uveitis, arthritis, and erythema nodosum. The treatment includes medical suppression of the inflammatory reaction and surgical resection. The disease commonly recurs following surgical resection, often at the anastomotic site.

Early Crohn’s disease is a mucosal disorder characterized by aphthous lesions, which can be detected by a double contrast barium examination or endoscopy. The disease progresses to the submucosa and eventually becomes transmural. Any portion of the gastrointestinal tract can be involved, although the terminal ileum is the most common site of disease. Extraintestinal involvement includes uveitis, arthritis, and erythema nodosum. The treatment includes medical suppression of the inflammatory reaction and surgical resection. The disease commonly recurs following surgical resection, often at the anastomotic site.

Radiologic

The radiologic diagnosis is typically made by a contrast examination such as an upper gastrointestinal examination, small-bowel follow-through (SBFT), enterocly-sis, or barium enema. The earliest changes of Crohn’s disease are aphthous lesions, which appear as a central fleck of barium surrounded by a translucent halo. These initial changes occur in the mucosal lymphoid tissue. The appearance is nonspecific and can be seen in other inflammatory diseases.

The radiologic diagnosis is typically made by a contrast examination such as an upper gastrointestinal examination, small-bowel follow-through (SBFT), enterocly-sis, or barium enema. The earliest changes of Crohn’s disease are aphthous lesions, which appear as a central fleck of barium surrounded by a translucent halo. These initial changes occur in the mucosal lymphoid tissue. The appearance is nonspecific and can be seen in other inflammatory diseases.

With progression of disease, mural thickening occurs, often >1 cm. The bowel wall thickening in Crohn’s disease is usually greater than that seen in ulcerative colitis. Asymmetric or discontinuous involvement of the gastrointestinal tract is characteristic, as opposed to the continuous involvement by ulcerative colitis. A typical nodular, cobblestone appearance is seen consisting of longitudinally oriented ulcerations.

With progression of disease, mural thickening occurs, often >1 cm. The bowel wall thickening in Crohn’s disease is usually greater than that seen in ulcerative colitis. Asymmetric or discontinuous involvement of the gastrointestinal tract is characteristic, as opposed to the continuous involvement by ulcerative colitis. A typical nodular, cobblestone appearance is seen consisting of longitudinally oriented ulcerations.

The terminal ileum is the most common site of involvement. Techniques to delineate the terminal ileum include enteroclysis, peroral pneumocolon, and a prone-angled compression view on SBFT. Strictures, fistulae, and abscess formation are more commonly seen in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis.

The terminal ileum is the most common site of involvement. Techniques to delineate the terminal ileum include enteroclysis, peroral pneumocolon, and a prone-angled compression view on SBFT. Strictures, fistulae, and abscess formation are more commonly seen in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis.

CT demonstrates the extraluminal extent of disease. The most common CT finding in Crohn’s disease is bowel wall thickening. Another common finding is inflammatory change in the adjacent mesenteric fat. This mes-enteric change is seen in Crohn’s disease rather than ulcerative colitis as the former is a transmural process and the latter is limited to the mucosa. Fibrofatty proliferation of the mesentery and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes are also seen in Crohn’s disease. CT is also helpful in the diagnosis of abscess formation.

CT demonstrates the extraluminal extent of disease. The most common CT finding in Crohn’s disease is bowel wall thickening. Another common finding is inflammatory change in the adjacent mesenteric fat. This mes-enteric change is seen in Crohn’s disease rather than ulcerative colitis as the former is a transmural process and the latter is limited to the mucosa. Fibrofatty proliferation of the mesentery and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes are also seen in Crohn’s disease. CT is also helpful in the diagnosis of abscess formation.

SUGGESTED READING

Helper DJ. Medical management of Crohn’s disease: a guide for radiologists. Eur J Radiol 2009;69:371–374.

Hizawa K, Iida M, Kohrogi N, et al. Crohn’s disease: early recognition and progress of aphthous lesions. Radiology 1994;190:451–454.

Huprich JE, Rosen MP, Fidler JL, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria(R) on Crohn’s disease. J Am Coll Radiol 2010;7:94–102.

Nanakawa S, Takahashi M, Takagi K, Takano M. The role of computed tomography in management of patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Imaging 1993;17:193–198.

Siddiki HA, Fidler JL, Fletcher JG, et al. Prospective comparison of state-of-the-art MR enterography and CT enterography in small-bowel Crohn’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:113–121.

Yue NC, Jones B. Crohn’s disease: prone-angled compression view in radiographic evaluation. Radiology 1993;187:577–580.

VINCENT H.S. LOW

HISTORY

A 61-year-old woman has frequent and severe episodes of abdominal pain and distention.

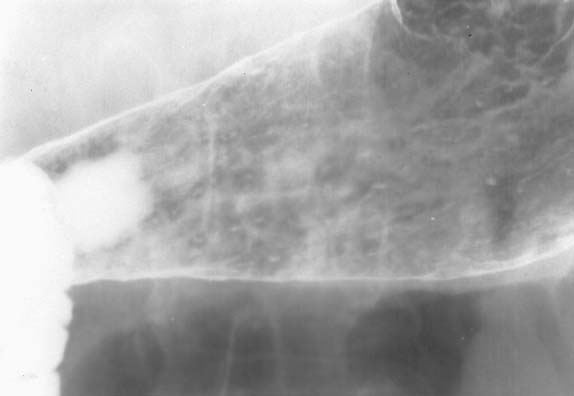

FIGURE 3-12A Barium small-bowel follow-through: 60-minute frontal overview. There is a large area of mass effect in the right mid abdomen, displacing loops of bowel. Caliber change is seen, with dilatation of proximal small bowel. Abnormal separation of loops of small bowel is present in the lower abdomen. There is spiculation of the margins of small bowel loops adjacent to these areas of separation and mass effect.

FIGURE 3-12A Barium small-bowel follow-through: 60-minute frontal overview. There is a large area of mass effect in the right mid abdomen, displacing loops of bowel. Caliber change is seen, with dilatation of proximal small bowel. Abnormal separation of loops of small bowel is present in the lower abdomen. There is spiculation of the margins of small bowel loops adjacent to these areas of separation and mass effect.

FIGURE 3-12B Barium small-bowel follow-through: spot view of the right lower quadrant. The mucosal folds are thickened, smooth in some areas and nodular in others. No specific intraluminal mass is seen.

FIGURE 3-12B Barium small-bowel follow-through: spot view of the right lower quadrant. The mucosal folds are thickened, smooth in some areas and nodular in others. No specific intraluminal mass is seen.

Mesenteric metastatic disease: Marked desmoplastic reaction may be seen with certain metastatic tumors, such as scirrhous gastrointestinal tract cancers and breast cancer.

Mesenteric metastatic disease: Marked desmoplastic reaction may be seen with certain metastatic tumors, such as scirrhous gastrointestinal tract cancers and breast cancer.