Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

Goodpasture syndrome, also known as anti–basement membrane antibody disease, is an autoimmune disorder characterized by repeated episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage, usually associated with glomerulonephritis and the presence of anti–glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies. Goodpasture syndrome is rare, with an incidence of approximately one patient per million population per year. It has a bimodal distribution with respect to age, with peaks at 20 to 30 and 60 to 70 years of age and a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3 : 2.

Clinical Presentation

The most common presenting symptom is hemoptysis, which occurs in about 80% to 95% of patients. The hemoptysis may range from mild to copious and life threatening. In more than 50% of patients, it precedes glomerulonephritis. On occasion, the hemoptysis may occur late in the course of the disease or be absent altogether. Other presenting symptoms include dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, pallor, cough, and, occasionally, frank hematuria. Although results of the initial urinalysis may be normal, proteinuria, hematuria, and cellular and granular casts almost invariably develop at some stage. More than 90% of patients have anti-GBM antibodies, and approximately 80% have crescentic glomerulonephritis on renal biopsy. More than 90% of patients have iron deficiency anemia resulting from blood loss from pulmonary hemorrhage.

Pathophysiology

Goodpasture syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the presence of autoantibodies against the glomerular and alveolar basement membranes. It has been suggested that environmental factors, such as smoking, previous hydrocarbon exposure, and infection, may play a role in triggering Goodpasture syndrome. In the kidney complement activation and inflammatory cell enzymes are responsible for glomerular damage. The precise pathogenesis of the pulmonary hemorrhage is unknown.

The main histologic findings of Goodpasture syndrome consist of pulmonary alveolar capillaritis, which results in diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage, and a segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis, which progresses to a crescentic nephritis. The capillaritis is identical to that of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) and microscopic polyangiitis and appears as a neutrophil infiltrate intimately associated with alveolar septa with or without fibrin thrombi and necrosis. Other histologic changes depend on the duration and severity of the disease at the time of examination but usually include hemosiderin-laden macrophages in alveolar airspaces and interstitial tissue and mild to moderate interstitial fibrosis. Immunofluorescence studies show characteristic linear staining most readily recognized in the glomerulus but also frequently evident in the alveolar capillary walls. Immunoglobulin (Ig)G is the usual antibody detected, although IgA and IgM are occasionally present as well.

Manifestations of the Disease

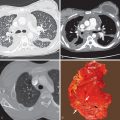

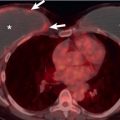

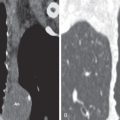

Radiography

In the early stages of the disease, the radiographic pattern is one of patchy hazy areas of increased opacity (ground-glass opacities) scattered fairly evenly throughout the lungs ( Fig. 47.1 ). With more severe hemorrhage, the pattern may progress to focal or confluent areas of consolidation often associated with air bronchograms ( Fig. 47.2 ). The opacities usually are widespread but may be more prominent in the perihilar areas and in the middle and lower lung zones. The apices and costophrenic angles are often spared. Although parenchymal involvement usually is bilateral, it is commonly asymmetric and occasionally may be unilateral. The chest radiograph may be normal in patients with diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage. In one review of 39 episodes of diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage in 23 patients, the radiograph was normal in 7 (18%) episodes. Serial radiographs show that within 2 to 3 days, the areas of consolidation are gradually replaced by a reticular or reticulonodular pattern, the distribution of which is identical to that of the airspace disease ( Fig. 47.3 ). This reticular pattern diminishes gradually during the next several days, and the appearance of the chest radiograph usually returns to normal about 10 to 12 days after the original episode. With repeated episodes of hemorrhage, increasing amounts of hemosiderin are deposited within the interstitial tissue and are associated with progressive fibrosis. In most cases the chest radiograph shows only partial clearing after each hemorrhagic episode, revealing persistence of a fine reticulonodular pattern indicative of the irreversible interstitial disease. Once these changes have developed, new episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage usually result in the typical pattern of airspace consolidation superimposed on the diffuse interstitial disease.