Head And Neck Cancer, Squamous

Todd M. Blodgett, MD

Alex Ryan, MD

Marios Papachristou, MD

Key Facts

Terminology

Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) nodes

Imaging Findings

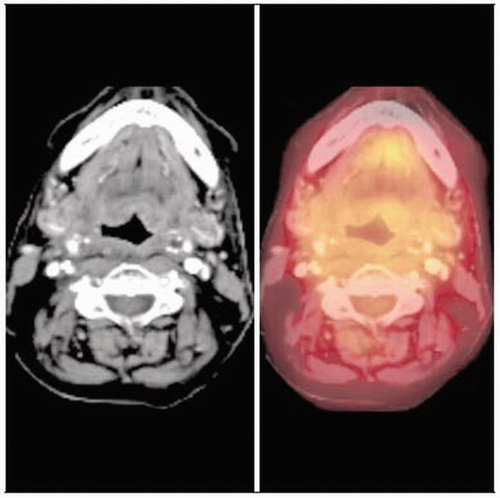

Intensely FDG-avid nodes in the neck on PET or PET/CT

Enlarged or necrotic lymph nodes in the neck ± enhancement on CT

PET/CT key for several clinical scenarios

Delineate extent of regional lymph node involvement

Detect distant metastases

Identify unknown primary tumor

Detect occasional synchronous primary

Combined PET/CT may offer additional localization information and improve interpreting physician’s confidence level

Overall sensitivity and specificity of FDG PET and PET/CT > 90%; PET/CT sensitivity 96% and specificity 98%

Top Differential Diagnoses

Abscess or Suppurative Nodes

Lymphoma

Physiologic Activity

Reactive Nodes

Diagnostic Checklist

Consider PET/CT in patients with primary tumors that are prone to bilateral metastases, which are often less conspicuous on conventional imaging

TERMINOLOGY

Abbreviations and Synonyms

Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN)

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) nodes

Unknown mucosal primary

Therapeutic assessment/restaging

Definitions

Primary, regional, and distant malignancy from tumors of squamous cell origin in the head and neck

Primary unknown: Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the neck without an identifiable mucosal primary lesion

Undetectable mucosal lesions by clinical exam or

Negative anatomical imaging

Head and neck cancers include those arising from the lip, oral cavity, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, pharynx, and larynx

90-95% are squamous cell carcinomas arising from mucosal linings of upper aerodigestive tract

IMAGING FINDINGS

General Features

Best diagnostic clue

Intensely FDG-avid nodes in the neck on PET or PET/CT

Enlarged or necrotic lymph nodes in the neck ± enhancement on CT

Primary unknown

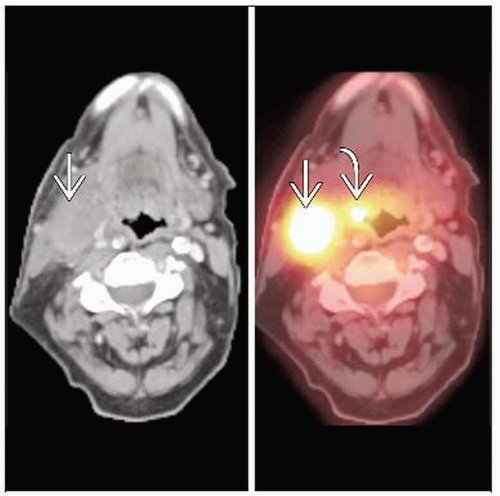

PET shows asymmetrical focal fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake, with or without an identifiable abnormality on CT

Sensitivity for PET and PET/CT is 26-43% in cases where primary has eluded diagnosis

Fused PET/CT images often helpful for determining whether potential FDG abnormalities are mucosal lesions

Helpful for directing clinicians to areas for directed biopsies

Intense FDG activity in or around treated primary tumor with corresponding CT evidence of residual tumor

Location

Primary squamous cell lesions may involve any mucosal surface

Commonly involve the base of tongue, tonsils, or adenoids

Mucosal surfaces of the oropharynx, nasopharynx, and hypopharynx

Lymph node metastases involve neck nodes in expected drainage pattern based on primary tumor

SCCHN has high propensity to harbor malignancy in small lymph nodes

Most common metastatic sites: Lung, liver, skeletal system

Size

Early primary SCCHN may be undetectable (unknown primary SCCHN)

Lymph node metastases may range in size from normal (< 1 cm) to several centimeters

Morphology

Mass effect, abnormal enhancement, or necrosis may exist in larger tumors

Fatty lymph node hilum usually denotes benign lesion on CT (may be positive on PET if occult malignancy present)

Indistinct borders usually denote extranodal spread

Imaging Recommendations

Best imaging tool

PET/CT key for several clinical scenarios

Delineate extent of regional lymph node involvement

Detect distant metastases

Further evaluate potentially abnormal findings on another exam, such as mediastinal adenopathy detected by chest CT

Identify unknown primary tumor

Detect occasional synchronous primary

Monitor treatment response to select appropriate patients for salvage surgery

Conduct long-term surveillance for recurrence and metastases

Check any patient who presents with clinical evidence of recurrent disease

TNM staging

MR better than CT for specific questions such as presence of perineural spread or invasion of bone marrow

N stage

CT generally superior to MR for detection of regional lymph node metastases

M stage

Only patients at substantial risk of nodal or hematogenous metastases, T3 or T4, should undergo routine PET/CT for staging

Combined PET/CT may offer additional localization information and improve interpreting physician’s confidence level

Overall sensitivity and specificity of FDG PET and PET/CT > 90%; PET/CT sensitivity 96% and specificity 98%

PET/CT more helpful for radiation therapy planning; can lead to changes in gross tumor volume

Extended field FDG PET staging may detect disease outside of the head and neck in up to 21% of patients with head and neck cancer

Sensitivity for PET and PET/CT 26-43% in which primary has eluded diagnosis

Sensitivity for PET/CT better for accurate localization of lesion and directed biopsy recommendations

MR typically initial imaging study of choice for staging

Compared to noncontrast PET/CT, more accurate delineation of tumor extent, perineural involvement, and intracranial extent

Nearly comparable in accuracy in detecting regional LN metastases

Contrast-enhanced CT used only in laryngeal cancer; PET/CECT may be better for this indication than MR or CECT alone

Restaging: Combined PET/CT is more sensitive and specific than CT alone

Protocol advice

High resolution PET/CT from top of head to carina using standard head and neck protocol (especially for unknown primary)

Scan with arms down on PET/CT to avoid beam hardening artifact

Whole-body scan performed with arms above head and shorter acquisition time

Use neck immobilization device

Scan in mask for radiation planning PET/CT

Display images with PET intensity kept low-moderate (avoid “blooming”)

Pre-treatment with benzodiazepines in patients with excessive muscular FDG uptake on FDG PET

Warm patients before and after injection of FDG to reduce brown fat FDG uptake

Restaging

Scan with arms down, CECT, and neck immobilization device

Consider dual-time point imaging to help differentiate between inflammatory and neoplastic FDG activity

CT Findings

CECT: Early enhancement, rim enhancement, central necrosis, indistinct borders

Post-therapy neck difficult to interpret

Accuracy of CT ranges from 50-70%

Loss of fat planes and extensive post-surgical changes reduce the specificity of CT

Distortion of normal anatomy can be due to bony-cartilaginous necrosis, edema, and desmoplastic changes

CT may show enhancement, necrosis, or mass effect with residual/recurrent tumor

Best method of detection using CECT is serial examination

CT and MR may be negative for unknown primary if

Tumor is subtle or difficult to separate from adjacent normal structures (as with lingual tonsillar tissue)

Primary is superficial or very small

Scan is limited by motion or streak artifact

Abnormal size criteria for CT: ≥ 1 cm for most nodes; ≥ 1.5 cm for level I-II nodes; ≥ 8 mm for retropharyngeal nodes

FDG PET can detect smaller positive nodes (limited by spatial resolution)

Central necrosis specific for malignancy, but it is a late marker of metastatic adenopathy

Usually seen only in nodes ≥ 20 mm, which is beyond the typical cutoff of 10 mm for suspicion of malignancy

Contrast enhancement generally improves detection of malignancy

Round morphology more suspicious than reniform

Nuclear Medicine Findings

PET/CT is more accurate than PET and CT separately; PET is more accurate than CT alone

FDG PET sensitivity and specificity for residual disease 90% and 83%, respectively

PET/CT sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy 98%, 92%, and 94%, respectively

PET/CT decreases number of equivocal lesions by ˜ 50% and provides improved biopsy localization information

74% better localization with PET/CT compared to PET in regions previously treated; 58% for untreated regions

Initial diagnosis

Squamous cell carcinoma almost always FDG avid

Look for primary lesion along the mucosal surfaces

Unknown primary: FDG PET typically shows focal asymmetrical FDG uptake in the mucosal primary

5-10% of cases involve primary that cannot be found by physical exam, panendoscopy, or conventional radiographic imaging

PET/CT has been shown to find primary in 40% of patients whose primary was not identified in office or with surgical panendoscopy

False negatives with PET/CT means that this modality is a supplement to, but not a substitute for, endoscopy and biopsy with unknown primary

FDG PET shows no advantage over traditional techniques for identification and characterization of primary head/neck tumors for stage I/II lesions

Rarely adds information regarding initial T staging of primary

Exception is unknown primary

Staging

Screening for distant metastases advised for patients who have

Four or more lymph node metastases

Bilateral positive nodes

Nodes greater than 6 cm

Zone 4 nodes

Recurrent SCCHN

Second primary tumor

In one study, 24% of patients newly diagnosed with SCCA of the oral cavity had distant metastases picked up by PET/CT

However, PET/CT cannot preclude neck dissection in patients with advanced primaries but clinically node-negative necks

PET/CT may alter TNM score in 30-35% of patients by identifying nodal disease not apparent on CT, MR, or clinical exam

PET/CT has advantage in identifying distant disease because it can detect occult metastatic disease (e.g., subtle bone metastases)

Present in as many as 10% of patients with advanced local-regional disease

PET may alter treatment in many patients, decreasing toxic wide-field radiotherapy

Unclear whether PET/CT useful in identification of nodal metastases in patients with SCCHN and N0 necks on exam

Stage III/IV patients have high risk of distant metastases, creating a greater role for FDG PET

PET has a distinct advantage over CT/bronchoscopy, especially in the lung

Target volumes for IMRT and stereotactic radiosurgery may be modified in as many as 20% of cases with PET/CT vs. CT alone

PET/CT used primarily to include normal-sized lymph nodes with increased metabolic activity as part of high dose target volume

Helpful for contouring primary tumors whose borders are difficult to distinguish by anatomic imaging alone, as with some tongue-based tumors

PET/CT limited in staging local lymph node involvement if patient’s disease is clinically stage N0 after physical examination and anatomic imaging

Due to limited spatial resolution

Selective neck dissection or sentinal lymph node biopsy is more definitive

However, even in stage N0 disease PET/CT may be useful

Serves as a baseline to differentiate incidental physiologic FDG-avid foci from malignant foci on subsequent post-treatment exams

Otherwise a significant interpretive challenge if comparison images are not available

Restaging

Following surgery, no detectable tumor should be present

Variable amounts of post-surgical change expected

Post-surgery: Usually wait 4-6 weeks after to reevaluate with PET and PET/CT to avoid false positive studies due to inflammation

Reevaluation following surgery may be particularly helpful in cases where surgical margins are positive

Post-radiation

Positive PET one month after XRT has a positive predictive value of ˜ 100%

Negative PET one month after XRT has a lower negative predictive value (14%) early; fewer false negatives with longer follow-up period

Response to therapy

Following chemoradiation, metabolic response may precede reductions in tumor volume

Post-chemotherapy (approximately 1 month after completion): Sensitivity and specificity of FDG PET 90% and 83%

Little data evaluating early response to chemotherapy

Inflammatory changes seen with radiotherapy are not seen, and PET can be performed at earlier time point, such as 4-8 weeks

Post-chemoradiation

PET/CT has high negative predictive value and allows confident exclusion of residual cancer, thereby deferring planned neck dissection

Pitfalls and limitations

Several structures in the neck with variable physiologic FDG activity

Common muscles with asymmetrical FDG activity: Pterygoids, sternocleidomastoid, strap muscles, and mylohyoid

Glands: Salivary glands (submandibular and parotid); can have intense FDG activity following some chemo regimens

Lymphoid tissue: Lingual tonsils, palatine tonsils, and adenoids (Waldeyer ring)

Brown fat: Can be symmetrical or asymmetrical, can be focal anywhere in the neck

FDG PET may not detect small areas of residual/recurrent disease, leading to early false negative exams after therapy

PET frequently fails to identify hypermetabolism in areas of marrow space infiltration and perineural extension

Cartilage necrosis may be FDG avid indefinitely

Cricoarytenoids typically FDG avid and often asymmetric

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Metastatic Disease from Thyroid or Melanoma

May look identical to squamous cell carcinoma

Abscess or Suppurative Nodes

Usually has central necrosis; identical in appearance to necrotic lymph node

FDG PET not helpful for differentiation; biopsy required

Often indistinguishable from tumor; correlate clinically

Lymphoma

Difficult to differentiate from SCCHN based on imaging; associated mucosal lesion favors SCCHN

NHL: May mimic tonsillar inflammatory disease

Residual/Recurrent Malignancy

Often indistinguishable from abscess/inflammation

Short-term serial evaluation very helpful

CT may show asymmetrical mass effect

Radiation-Induced Inflammation

FDG uptake from inflammation usually present for 4-8 weeks following therapy

Osteoradionecrosis can cause false positive early (before frank necrosis causes negative PET)

Dual-time point PET imaging at 1 hour and 3 hour post FDG injection may be helpful in differentiating tumor vs. inflammation

FDG uptake from 1-3 hours: Tumor may increase; inflammation may plateau or decrease

Physiologic Activity

Benign tonsil FDG uptake typically will be symmetrical but can be intense

Muscle activity may be focal and asymmetrical

Correlate PET with CT; pre-treatment with benzodiazepines may reduce muscle uptake

Measure Hounsfield units (HU); -50 to -150 compatible with brown fat

Warm patient before FDG injection to reduce brown fat uptake of FDG

PATHOLOGY

General Features

General path comments

Nodal level classification scheme

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS)

Level IA: Submental nodes between anterior digastrics

Level IB: Submandibular, lateral to IA anterior to the posterior margin of submandibular gland (SMG)

Level IIA: Upper internal jugular nodes; anterior, lateral, or posterior and touching the jugular vein

Level IIB: Posterior, not touching jugular

Level III: Mid-internal jugular nodes, extend from inferior hyoid to cricoid arch

Level IV: Low internal jugular nodes, extend from cricoid arch to the level of the clavicle

Level V: Spinal accessory group, nodes in the posterior triangle; level VA: Above cricoid; level VB: Below inferior cricoid border

Level VI: Upper visceral nodes; between the carotid arteries from bottom of the hyoid to the top of the manubrium

Level VII: Superior mediastinal nodes; between the carotid arteries from below the top of the manubrium above the innominate vein

Supraclavicular nodes: At or caudal to the level of the clavicle and lateral to the carotid artery

Retropharyngeal nodes: Within 2 cm of the skull base medial to the carotid arteries

Parotid: Nodes within the parotid gland

Initial workup with physical exam, office endoscopy, and MR/CT

If definitive for nodal disease, PET/CT is appropriate for accurate evaluation of nodal metastases

Suggestive PET/CT findings should prompt fine needle aspiration (FNA)

If FNA is negative, definitive treatment is pursued and PET/CT is optional, to serve as baseline prior to therapy

If a focus of unknown primary is suspected on metabolic imaging

Panendoscopy and frozen section biopsy

Panendoscopy includes oropharynx, hypopharynx, nasopharynx, larynx, and upper esophagus

If negative, further biopsy specimens may be obtained from most common sites for primary tumors

Base of tongue

Nasopharynx

Contralateral tonsillar fossa

Pyriform sinus

Ipsilateral tonsillar fossa

Reassessment

Biopsy areas that appear suspicious on PET or PET/CT

Alternatively, short-term interval follow-up PET or PET/CT

Etiology: Smoking, chewing tobacco, alcohol abuse

Epidemiology

SCCHN newly diagnosed in 40,000 patients annually in United States

Mortality is 23%

Average 5 year survival 56%

Associated abnormalities: Risk factors also predispose to esophageal and lung cancer

Staging, Grading, or Classification Criteria

T stage: Assessment requires knowledge of size of primary lesions, depth of invasion, and involvement of surrounding structures

N stage: AJCC characteristics include number of nodes involved, size of nodes, location (laterality and level), and morphology

Staging of SCCHN requires

Complete history and physical

Histologic confirmation

Characterization of primary

Recognition of local/regional nodal disease

Identification of distant metastatic disease

CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

Most common signs/symptoms

May present with pain associated with primary mass or neck mass

Symptoms of residual/recurrent tumor overlap with post-treatment complications; pain is most common

Other signs/symptoms: Mass on clinical exam

Demographics

Age: Generally > 40-45 years

Gender: M > F

Natural History & Prognosis

Nodal metastasis is most accurate prognostic factor for SCCHN

Unilateral nodal involvement indicates 50% reduction in expected lifespan; bilateral nodal involvement indicates 75% reduction

10 year survival drops from 85% to 10-40% in patients with positive nodes

Carotid artery involvement or encasement portends dismal prognosis with 100% mortality

Majority of patients do not have metastatic disease within cervical nodes at presentation

20% risk of occult metastasis in patients with clinically node-negative necks

10-15% of patients with SCCHN will present with distant metastases

Unknown primary

PET and PET/CT can help direct biopsy

2-9% of SCCHN patients present with cervical lymph node metastases without clear evidence of primary site

If imaging is negative, patients are usually followed with serial imaging evaluation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree