3 Hematuria Hematuria is a very common clinical problem that challenges both primary care and specialty physicians. Hematuria may be defined as gross or microscopic and symptomatic or asymptomatic. Asymptomatic hematuria occurs in ~13% of men over 35 and women over 55.1 Asymptomatic hematuria is defined as microscopic hematuria [three to five or more red blood cells (RBCs) per high-power field] seen on two of three urinalyses; one episode of 100 RBCs per high-power field; or gross hematuria.2 One or two RBCs per high-power field are found in ~15% of asymptomatic persons.1 Unfortunately, the degree of hematuria does not necessarily correlate with its significance. All hematuria requires evaluation. This discussion includes both gross and microscopic hematuria. This chapter does not discuss patients suspected of having a renal or ureteral calculus, who present with flank pain and hematuria. Only ~20% of patients with microscopic hematuria have a significant abnormality as the cause and only 4% have life-threatening lesions (Table 3–1).1,3–6 When gross hematuria occurs, almost 60% have significant abnormalities and 20% have life-threatening disorders.7 When lower abdominal symptoms are associated with hematuria, the cause is commonly in the lower urinary tract D a significant percentage will have treatable pathology.2,3 Table 3–1 lists the more common diseases, stratified by severity, that are associated with hematuria. It is not always clear that the associated diagnosis is the cause of the hematuria. In fact, only about half of the patients investigated for hematuria have a related diagnosis discovered in the initial evaluation. When the remaining, undiagnosed patients with persistent hematuria are followed, a small percentage will have a cause for hematuria detected within 3 years of the discovery of hematuria. These diseases include glomerulonephritis, calculi, and, rarely, bladder or prostate cancer.6 Because transient hematuria is common, the insistence on multiple positive tests is important when trying to separate disease from no disease. It can be useful to try to separate glomerular from nonglomerular hematuria. Findings that favor a glomerular source include cola-colored urine, renal insufficiency, red-cell casts, dysmorphic red cells, and proteinuria. Methods to assess red cell morphology have not been widely accepted in medical practice.8,9 Older patients and patients with frankly bloody urine are at higher risk for a significant lesion. Sixty percent of patients with painless gross hematuria will have a diagnosis made by a combination of imaging and cystoscopy. The majority of these diagnoses are not life threatening. Conversely, 40% of patients with gross hematuria have no diagnosis made.5,7 The vast majority of patients over the age of 50 who present with hematuria will have significant diseases. Because urological cancer is more common in males, those men over 50 who present with hematuria should have a complete and thorough evaluation of the urinary tract (Fig. 3–1).5,10

Differential Diagnosis

Life-Threatening and Significant Diseases |

Bladder cancer |

Renal cell carcinoma |

Transitional cell carcinoma of ureter or kidney |

Ureteral calculus |

Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

Prostate cancer |

Generalized renal parenchymal disease |

Moderately significant diseases |

Pyelonephritis |

Cystitis |

Hydronephrosis |

Bladder calculus |

Bladder diverticulum |

Urethral stricture |

Neurogenic bladder |

Prostatitis |

Insignificant Diseases |

Renal cyst |

Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

Urethritis |

Bladder diverticulum |

Caliceal diverticulum |

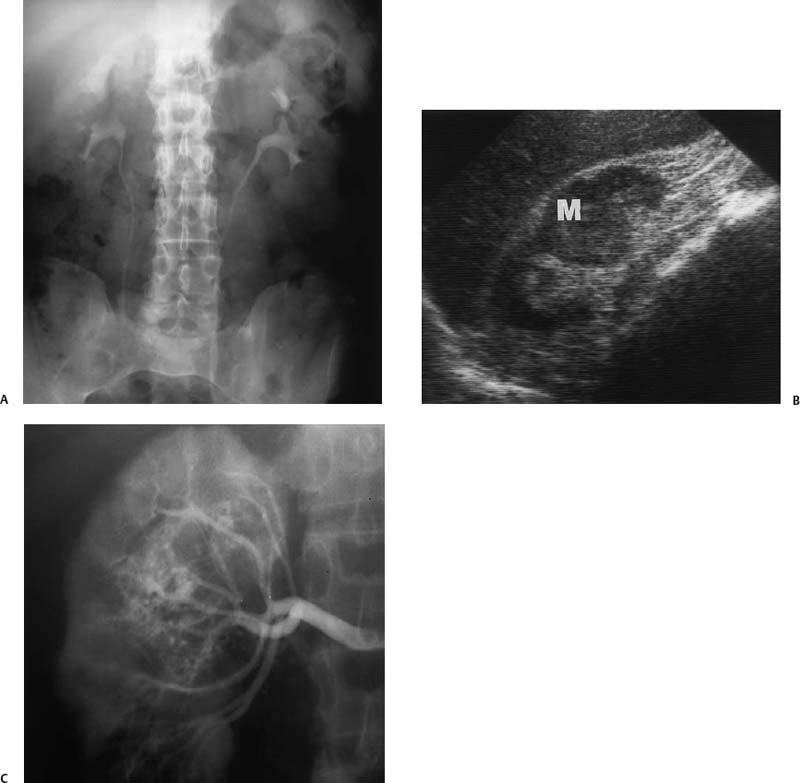

Figure 3–1 Central renal cell carcinoma in a 60-year-old man. (A) Intravenous pyelogram shows very subtle dilatation of upper pole collecting system on the right. Tomograms did not suggest a mass. (B) Right renal ultrasound shows a large solid mass (M) in the midportion of the kidney. (C) Arteriogram confirms typical findings of renal cell carcinoma.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Nonimaging Evaluation

In addition to imaging evaluations, common testing performed in patients with hematuria include (1) search for proteinuria (seen in glomerulopathies); (2) urine cytology; (3) urine culture; (4) renal function tests; and (5) endoscopic evaluations, including evaluation of the bladder, ureter, and renal collecting system.11 Appropriate sequencing of these procedures is important. The frequency with which invasive and more expensive procedures (e.g., ureteroscopy or retrograde pyelography) are used depends on the quality and reliability of the less invasive studies, particularly the imaging studies. Risk–benefit choices must be made when deciding whether to administer iodinated intravenous contrast media to a patient of a certain age or sex. This evaluation is made relative to the extent of hematuria and the chances of finding a significant or life-threatening abnormality. In general, meta-analyses and clinical decision-making models suggest that patients with hematuria who harbor a urological malignancy are over 90% curable, whereas the risk of adverse events from the evaluation is ~1%. Therefore, evaluation is always warranted except in women under 40, where the yield of pathology is less than the risk of adverse events.5,11–14

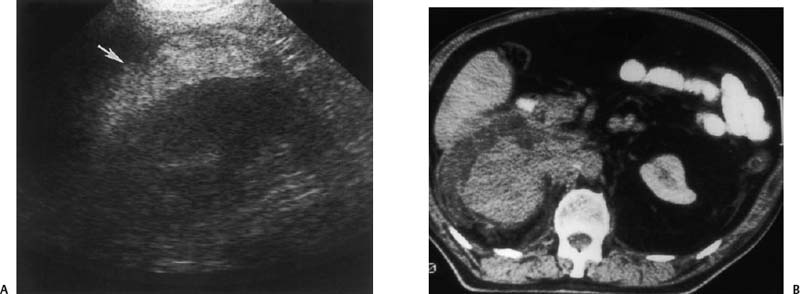

Figure 3–2 Infiltrative transitional cell carcinoma. (A) Ultrasound of the right kidney in a patient with gross hematuria. Normal renal architecture is absent and there is increased echogenicity in the perirenal space (arrow). (B) Computed tomogram demonstrates infiltrative neoplasm with perirenal hemorrhage. The kidney was surgically removed and contained extensive transitional cell carcinoma with spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage.

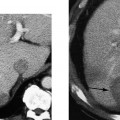

Figure 3–3 Small renal cell carcinoma. (A) A 55-year-old woman was initially investigated with ultrasound and a small solid mass (arrow) was discovered on the lateral cortex of the left kidney. (B) Computed tomogram confirms the solid nature of the mass (arrow) and suggests a neoplasm. A small renal cell carcinoma was removed surgically.

Imaging Other than Ultrasound

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree