Fig. 8.1

32-year-old female with PSC. MRCP (a) shows annular narrowing of the carrefour associated with mild dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts. ERCP (b) confirms MRI statements. Distal choledocic annular stenosis, missed at MRCP, is also depicted

8.2.1.7 Diagnosis with Imaging: Cholangiographic Signs

Imaging demonstration of diffuse, multifocal strictures and irregularities involving the medium-sized intrahepatic and/or medium- or large-sized extrahepatic ducts is the gold standard for diagnosing PSC (Fig. 8.1). Cholangiographic abnormalities include multiple strictures, saccular dilatations and irregularity of ductal margins [28]. Randomly distributed, short (1–2 mm), annular intrahepatic strictures alternating with normal or slightly dilated segments produce a beaded appearance. Some authors suggest “beading appearance” (Fig. 8.2) as the presence of more than three strictures with alternating dilatation along a bile duct [29]. Strictures usually occur at the bifurcation of ducts and are out of proportion to upstream ductal dilatation [14]. As the fibrosing process worsens, strictures increase and the ducts become obliterated: at this stage the peripheral ducts cannot be visualized at ERCP (“pruned tree” appearance) but are well detected by MRCP as well as complications such as diverticular like extroflessions, saccular dilatations, webs (focal 1–2 mm thick areas of incomplete circumferential narrowing) and biliary stones (Fig. 8.3) [14, 27]. Both intra- and extra-hepatic ducts are usually involved. Lesions are limited to intrahepatic ducts in less than 20 % of cases, and to extra-hepatic ducts in less than 10 %. Cystic duct, gallbladder and pancreatic duct involvement have been described [2]. MRCP and ERCP show different results depending on the involved biliary tract. ERCP ensures a better detection of choledocic irregularities and diameter alterations. The injection of contrast medium through the catheter placed in prepapillary position causes distension of the choledocic tract, allowing better opacification [30]. However, retrograde opacification shows the proximal end of a stricture but may fail to demonstrate the ductal anatomy distal to the stricture. MRCP shows better in visualizing periferical intra-hepatic ducts distal to severe strictures (Fig. 8.4) [30]. Intra-hepatic ductal dilatation is defined by the presence of intra-hepatic bile ducts with diameter equal or superior to that of central ducts or major than 3 mm. A mild dilatation has a maximum diameter of 4 mm, a moderate dilatation has a diameter between 4 and 6 mm and a severe dilatation is larger than 6 mm. There is evidence that the level of intra-hepatic bile duct visualization with MRCP is different between patients affected or not by PSC. In healthy individuals, central ducts contain enough bile in order to be detected by MRCP, while it is difficult to image minor ducts because they contain a negligible amount of bile. In PSC patients peripheral ducts can be imaged more effectively with MRCP in terms of dilatation, which is secondary to strictures in central ducts. Consequently, a good visualization of peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts with MRCP can alarm the radiologist about the presence of a stricture [27]. It should be noted that areas of minimal narrowing may be missed at MRCP and length of stenosis may be overestimated [30].

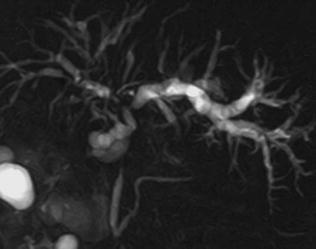

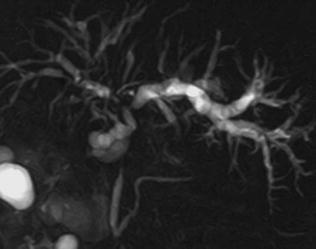

Fig. 8.2

46-year-old female. MRCP shows typical features of PSC with multiple strictures involving intra-hepatic bile ducts, giving a beaded-like appearance and a main stricture on the common bile duct

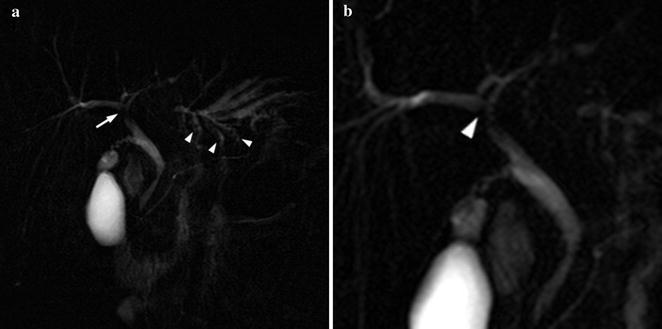

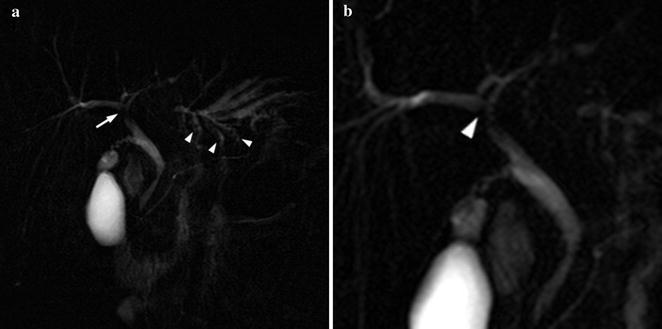

Fig. 8.3

25-year-old male PSC patient. MRCP (a) shows wide stenosis of the main left hepatic duct (thin arrow) with upstream dilatation of intra-hepatic bile ducts; note multiple stones (arrowheads) in the medium-sized intra-hepatic left ducts, as a result of bile stasis. Detailed view (b) shows focal (1.8 mm) incomplete circumferential stenosis, consistent with “web” of the proximal aspect of the right main duct (arrowhead). Irregular narrowing of the margins of the common bile duct is also depicted

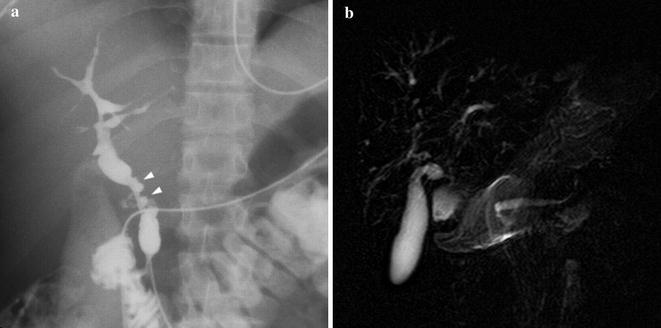

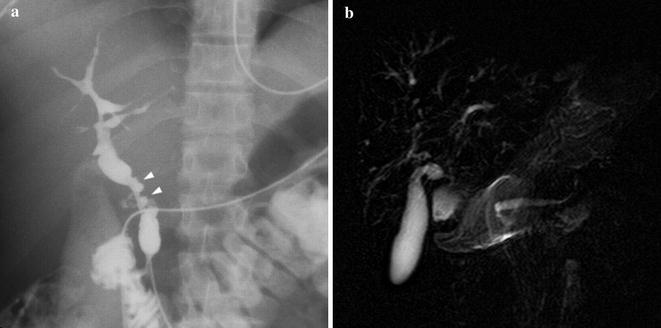

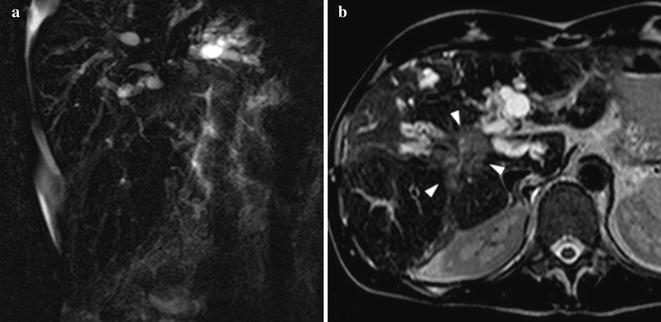

Fig. 8.4

28-year-old male PSC patient. Cholangiography (a) shows multiple irregular high-grade stenosis and saccular dilatations of the common bile duct (arrowheads). Peripheral ducts could not be visualized at the periphery of the liver (“pruned tree” appearance) because of upstream ducts stenosis. On the other hand, MRCP (b) enables to appreciate medium-sized intra-hepatic ducts, affected by diffuse, multifocal strictures. The common bile duct could not be depicted

8.2.1.8 Differential Diagnosis

Before the diagnosis of PSC is established, processes that mimic PSC at cholangiography must be excluded. Cholangiographic findings are similar in primary and secondary cholangitis [28] and a differential diagnosis on the basis of common imaging is not possible. It is not usually possible to differentiate PSC from chronic bacterial cholangitis, parasitic infection of the bile, cholangitis related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), IgG4-associated cholangitis, infiltrative diseases (such as sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, histiocytosis X) [14, 15]. The distinction between a benign dominant stricture and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) in a PSC patient is challenging (Figs. 8.5, 8.6). As the key cholangiographic features of PSC are annular strictures out of proportion to upstream dilatation due to extended fibrosis, when these ducts are overdilated other sclerosing processes such as ascending cholangitis or CCA on PSC should be considered. In a meta-analysis study [31] MRCP appeared as less reliable for differentiating malignant from benign causes of biliary obstruction than it was for detecting the presence of biliary obstruction in general. This lower accuracy in identifying a malignant cause may be due to its lower spatial resolution and inadequate depiction of the contour of strictures as compared with direct cholangiography (ERCP and PTC). As a matter of fact MRCP reveals only abnormalities in the duct lumen and needs to be combined with parenchymal transverse sections after contrast media administration to detect intra-hepatic CCA [32]. Recognition of typical CCA delayed accumulation and washout of contrast material, due to its fibrous centre allows a demonstration of extraductal anomalies suspected for CCA at contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. On MRI, periportal changes, manifesting as low signal intensity on T1w images and high signal intensity on T2w and T1w with late contrast enhancement images, are suggestive of CCA if their extent is greater than 1.5 cm. Cholangiographic features that suggest CCA include irregular high grade ductal narrowing with shouldered margins, rapid progression of the strictures, marked ductal dilatation proximal to strictures and polypoid lesions (Fig. 8.6) [14].

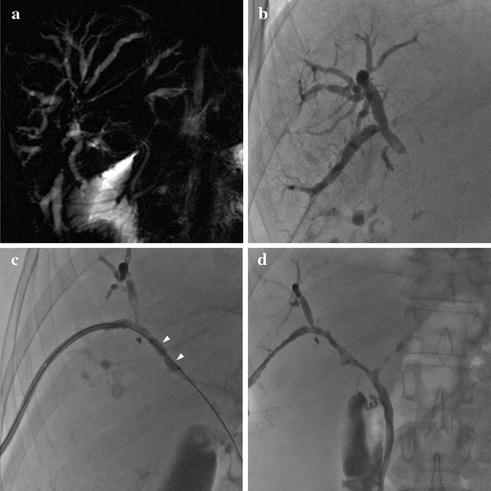

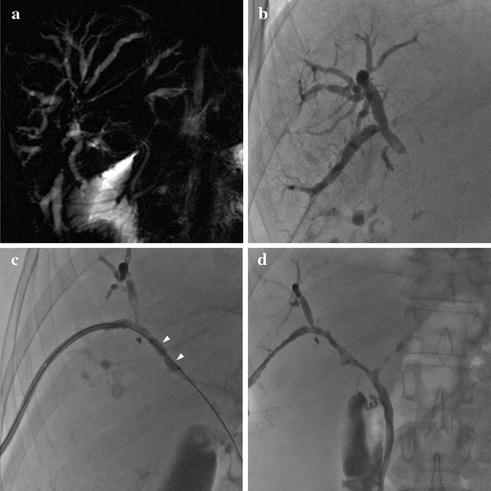

Fig. 8.5

48-year-old male patient with UC and CSP. MRCP a shows central stenosis of the biliary tree with marked upstream intra-hepatic ductal dilatation, suspected for CCA. Patient underwent PTC, which confirmed tight stenosis of the right main biliary duct (b). Bioptic samples excluded neoplasia. After percutaneous balloon dilatation (c) and 7 days, drainage resolution of the stenosis and restoration of bile flow were achieved (d)

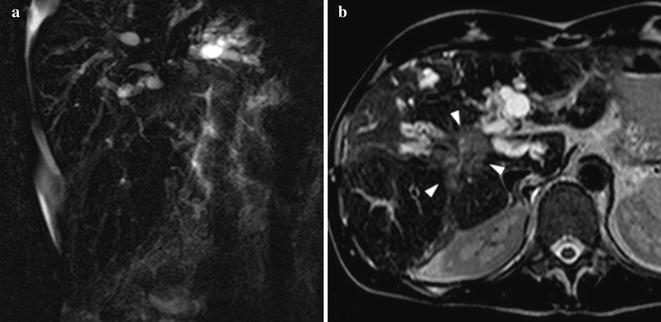

Fig. 8.6

49-year-old male patient with CSP and CCA. MRCP (a) shows central stenosis of the biliary tree with marked upstream irregular intra-hepatic ductal dilatation, suspected for CCA. Axial T2w image (b) shows 4 cm hilar hyperintense lesion (arrowheads) consistent with histologically proven CCA. Note perihepatic fluid collection

8.2.2 Less Common Bile Duct Disorders in IBD-CU: Variants of PSC

8.2.2.1 Small Duct PSC

A variant of PSC called small duct PSC (sdPSC) is applied to the small percentage of patients with characteristic clinical and biochemical findings of PSC but with a normal cholangiography. The absence of macroscopic abnormalities at MRCP needs a liver biopsy for the diagnosis of sdPSC [8]. This entity was initially termed ‘pericholangitis’, and includes less than 5 % of PSC cases [15]. SdPSC may be a specific form of HPB disorder associated with IBD and US criteria for the diagnosis mandates the presence of co-existing IBD. In contrast, the presence of IBD was not a part of the criteria to classify sdPSC used in Europe [1]. Unlike the classical form, the presence of IBD does not impact survival in sdPSC [7, 33]. SdPSC appears to have a more favourable prognosis than large duct disease with a median survival of 29.5 years compared to 17 years for classical PSC and CCA has not been described in this variant [3, 7, 15]. Approximately 28 % of patients progress to the large duct variant over a median of 7.4 years [4, 7] which suggests that sdPSC may be an earlier stage of PSC with progression disease to classical PSC and/or end-stage liver disease and consequent need of OLT [3, 34].

8.2.2.2 IgG4-Associated Sclerosing Cholangitis

IgG4-associated cholangitis (IAC) has been proposed as a term to describe the biliary manifestations of the serum immunoglobulin G4-related systemic disease (ISD), which is a steroid responsive multisystem fibro-inflammatory disorder in which affected organs have a characteristic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate rich in IgG4-positive cells associated with intense sclerosis [15]. Compared with PSC, IAC presents at an older age (mean age, 62 vs. 40 years) and is uncommon in IBD patients (5 %). The systemic fibro-inflammatory process of ISD also involves pancreas, salivary and lacrimal glands, retroperitoneum, kidney and lymph nodes. Thus, other organ involvement is an important clue in the diagnosis of IAC. The association of IAC with autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) has clinical relevance. Studies from the Mayo Clinic revealed that 92.5 % of patients with IAC suffer from AIP, whereas IAC may occur in 20–90 % of cases of AIP [35]. IAC should be suspected in unexplained biliary strictures associated with increased serum IgG4 and unexplained pancreatic disease [36]. The prevalence of IAC in PSC patients is reported between 7 and 11.6 % [35]. Nevertheless, IAC appears to be a histologically and pathogenetically distinct entity with dramatic response to corticosteroid therapy in contrast to the progressive and refractory nature of PSC [1]. That is why in all patients with possible PSC, the AASLD guidelines suggest obtaining IgG4 levels to exclude IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis [15]. At MRCP and ERCP, IAC is characterized by bile duct wall thickening and biliary strictures, which closely resembles PSC [36].

8.2.2.3 Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis/Autoimmune Hepatitis (PSC/AIH) Overlap Syndrome

Patients with IBD, especially UC, are also at increased risk of other immune-mediated liver disease including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). AIH and PSC may also occur within the same individual. It remains unclear if this represents the independent occurrence of both diseases, the presence of a distinct overlap syndrome or different stages in the evolution of a single disease entity [4]. PSC/AIH overlap syndrome is characterized by clinical, biochemical and histological features of autoimmune hepatitis and typical cholangiographic findings of PSC [15]. Typically, patients with IBD develop AIH first and subsequently go on to develop PSC. Patients with PSC/AIH seem to take benefit from treatment with immunosuppressive medications and may have a better prognosis as compared to patients with an isolated PSC [7, 34].

8.3 Liver Involvement

8.3.1 Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Fatty changes are commonly seen (from 13 to almost 100 %) in liver biopsy specimens or at US examination in patients with UC [1, 34] and correlate with colitis severity. This contributes a significant proportion of patients with abnormal LFTs in UC patients. The use of corticosteroids in IBD may be a contributing factor for the development of fatty liver.

8.3.2 Nodular Regenerative Hyperplasia: Medication-Associated Liver Disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree