Fig. 1

Digital model of S. Justin’s church. It allows to represent building’s architectural characteristics

Fig. 2

3D photorealistic model of the church of S. Paul near L’Aquila (XIII–XVIII–XX centuries)

Fig. 3

Casa del Balilla in Ascoli Piceno (1933–1934). Rendering with the perspective section of the tower and office block

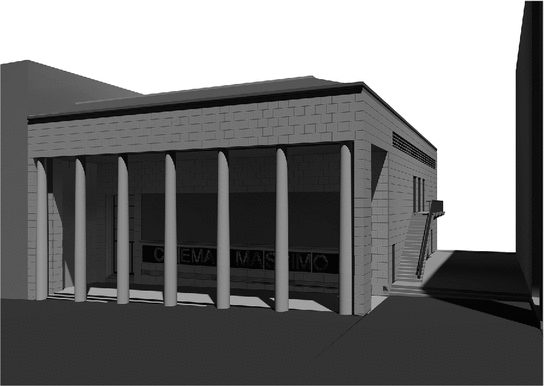

Fig. 4

Casa del Balilla in Ascoli Piceno Isometric rendering and perspective section of the cinema. You can see the office block with a tower, the hall of the gym, cinema

Fig. 5

Casa del Balilla in Ascoli Piceno. Render isometric split from the bottom. Although internally the buildings are connected, each has its own entrance on different elevations

Fig. 6

Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro in Chieti (1933–1934). Rendering of the principal front, characterized by two helical stairs to reach the roof garden

Important contributions are related to the modern architecture. The publication of 2001 titled Architettura Disegno Modello [Architecture Drawing Model], editors Piero Albisinni and Laura De Carlo, proposes an experience based on the use of 3D models for the graphical analysis of the works of Giovanni Michelucci, Maurizio Sacripanti and Leonardo Savioli. The study, that starts from original drawings, favours the analysis of these authors and of their works in relation to their historical context. 3D models, sectioned and/or exploded, with the analysis of selected components, promote critical representations [1].

Livio Sacchi, aiming to a close examination of the theories underlying compositional choices, presents the virtual reconstruction of some unrealized buildings—the buildings represented in Studi per la Città Nuova by Antonio Sant’Elia (1913–1914) and the Danteum by Giuseppe Terragni (1938)—as well as of a series of architectures built in the modern age, in particular the ones of the EUR district (1935–1936) in Rome [66].

Among the studies on the use of models guided by Riccardo Migliari, we remember those who have, as case studies, the Maison Citrohan of Le Corbusier and the Danteum of Giuseppe Terragni. In particular, with regard to the second one we observe the particular attention placed in setting the project, not realized, in the historical context of the city of Rome [52].

The theme of modern movement studying through digital modelling, in order to investigate and experience buildings no longer existing, it’s presented by Francesco Maggio and Marcella Villa with the digital reconstruction of houses realized for the V Triennale of Milan in 1933, and then demolished [47]. Francesco Maggio also deals with the study of two existing buildings in Agrigento: the Balilla’s House by Enrico del Debbio (1929) and the Post Office building by Angiolo Mazzoni (1931–1939) [46].

Fig. 7

School in Teramo. Isometric render split from the bottom. In correspondence with the entrance there is the Aula Magna in the courtyard; in front there is the gym that can communicate with the court or directly to the backside

And similarly Stefano Brusaporci uses 3D models in his essay on modern Italian architecture [14] (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7).

Rodolfo Maria Strollo, in a study on the complex of the observatory of Tusculum (1939), not only presents the surveying model, but uses models—derived from original drawings—to compare different planning solutions, in order to analyze for each one the figurative and material values, and at the same time to reconstruct the events that led to the final design configuration [63].

The condition of the digital model to be freely represented, interrogated and browsed, in time and space, according to broader media, semiotic and epistemological schemes, compared to traditional 2D drawings, favours the study and the communication of architectonical heritage’s values and characteristics. With a risk of aestheticization own sake [48]—a “Dionysian tension” of “absolute appear” in the words of Purini [56, p. 95] )—but with new and relevant scientific virtue.

Obviously the case studies cited are not exhaustive; they want to represent the contents of a line of research that can benefit greatly from the development of information technology but which has the presupposition of its methodological application in a depth historical analysis, in a careful architectural survey, in a wise modeling project and in an intelligent and critical use of the digital model.

4 Case Study: The “Cinema Massimo” in L’Aquila

The “Cinema Massimo” in L’Aquila, commissioned by the Istituto Nazionale Fascista Assicurazione contro gli Infortuni sul Lavoro, was planned by the roman architect Luigi Ciarlini between 1940 and 1941 and built between 1943 and 1947 [14]. The project is part of the renovation of the historical cities and belongs to that process of social buildings development, promoted by the Fascist government. In this period were built many constructions for directional activities and social services such as schools, hospitals, government agencies offices, case del Fascio, buildings for workers’ club, etc. There are “new” building typologies and among them a particular importance was given to the cinema for cultural purposes and propaganda. The renovation of L’Aquila historical city had already begun in the second half of the nineteenth century [22], focusing on the widening of Corso Federico II, the main axis of the urban plan, with the purpose, never fully completed, to build continuous porticos along the main street’s sides.

The typological-distributive system of the Cinema Massimo follows from the requirements of context insertion, with the integration of the external space of the portico with the building project (Fig. 8). From the porticos, characterized by columns with entasis, you can enter in the foyer which is placed beside to the hall and interior service spaces. On the other side, the hall overlooks directly the outside through safety exits. From a constructive and formal point of view, the building is fully into the architectural and historical context of the ’30s and ’40s in Italy, when it began the structures building with reinforced concrete, but without the figurative value present in the European avant-garde. In fact, the Italian architecture keeps a close relationship with the formal solutions previous to the introduction of frame-systems with the presence of walls, no-loadbearing function, and of composite structures. Besides for the period are important: the search for a modern monumental style by the using of classical language without decorative elements, the admixture of elements in an eclectic style and the search on finishing materials, conditioned by the needs of autarchy. In fact in the final period of the fascist regime, the Italian state was isolated in the international context.

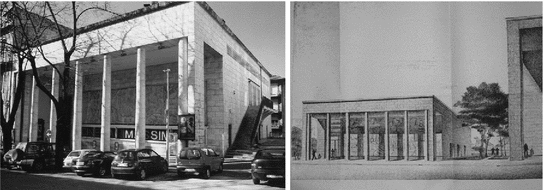

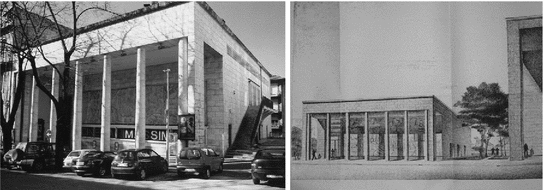

Fig. 8

Cinema Massimo in L’Aquila. The principal front in an actual photo and in a project’s perspective drawing

Fig. 9

Original project drawings of Cinema Massimo in L’Aquila: Carpentry and executive façade with constructive details

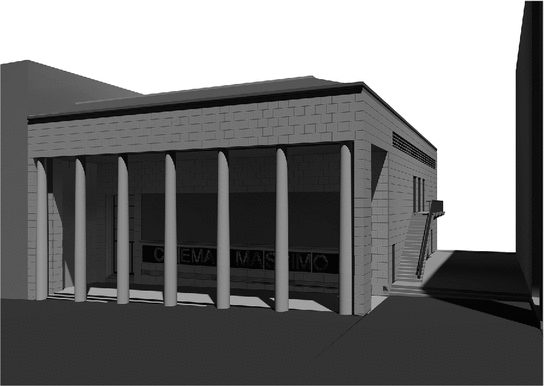

Fig. 10

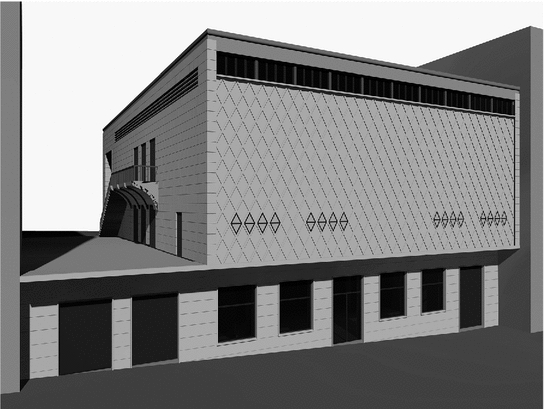

3D Model of the Cinema Massimo in L’Aquila. Rendering with perspective view of the principal front.

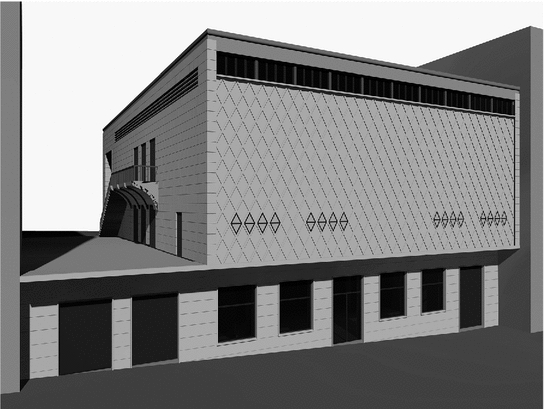

Fig. 11

Cinema Massimo in L’Aquila. Rendering with perspective view of the back front

Fig. 12

Cinema Massimo in L’Aquila. Rendering with perspective section of the foyer

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree