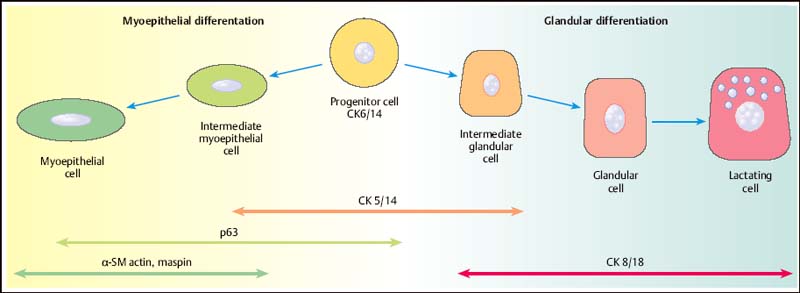

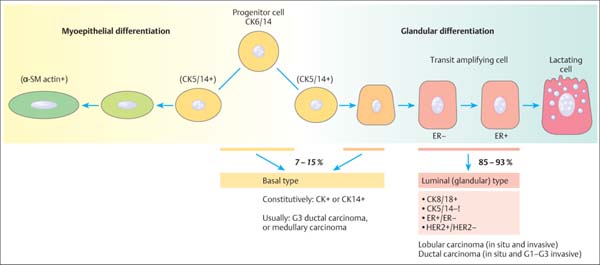

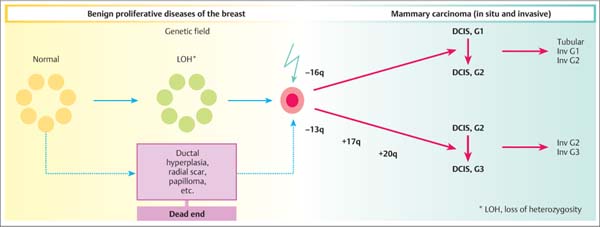

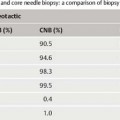

13 Histologic Evaluation of Core Needle Biopsy Specimens Core needle biopsy. Sampling cores of tissue through minimally invasive biopsy (MIB) now plays an important role in breast diagnosis. Core needle biopsy (CNB) and vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) are two widely used techniques. A core biopsy specimen is well suited for histologic examination: it can provide a definite diagnosis of benign lesions routinely—not just in individual cases —unlike the cytologic specimen obtained by fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). Furthermore, far better information regarding microcalcification and architectural distortion can be obtained from tissue samples than from single cells of cytologic specimens. Sensitivity and specificity. The sensitivity and specificity of CNB depend on the biopsy target and on the method of guidance selected. Ultrasound (US)-guided CNB of focal lesions is associated with higher absolute specificity and sensitivity than stereo-tactic core biopsy, which is mostly used to examine microcalcifications and architectural distortion and, far less often, focal lesions. In a meta-analysis of 17 108 biopsies, Britton and coworkers determined a sensitivity of 90.5% and a specificity of 96.7% for stereotactic core biopsy and 98.3% and 98.7%, respectively, for US-guided CNB (Britton, 1999). CNB is therefore superior to FNAB in both these diagnostic situations (for detailed data and a comparison with FNAB, see Chapter 12) and is the preferred method for the diagnosis of nonpalpable lesions (Ibrahim et al, 2001; Shannon et al, 2001; Britton and McCann, 1999; European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, 2006). Classification systems. Although a diagnosis based on the results garnered from CNBs poses far higher intellectual demands on the pathologist, the basic principles of morphologic breast diagnosis are valid here. In recent years, the Royal College of Pathologists (Guidelines Working Group of the National Coordinating Committee for Breast Pathology, 2005), the College of American Pathologists (Fitzgibbons et al, 1998), the European Working Group for Breast Screening Pathology (Wells et al, 2006a), and the World Health Organization (WHO; Tavassoli and Devilee, 2003) have issued almost identical classification systems for proliferative lesions of the mammary gland. In the present chapter, we use a three-pronged classification system of benign proliferative lesions, precursor lesions, and invasive carcinoma. Fig. 13.1 Progenitor cell concept of the mammary epithelium. Proliferative lesions. The progenitor cell concept of the mammary epithelium has led to a better understanding of proliferative breast lesions. Data obtained by using immunofluorescence microscopy show that the normal mammary epithelium contains progenitor cells that develop into differentiated glandular and/or myoepithelial cells (Boecker et al, 2002; Dontu et al, 2003). These cell types differ in morphology and in their immunohistochemical properties. Progenitor cells contain the cytokeratins CK5 and CK14, whereas differentiated glandular epithelia contain the cytokeratins CK8 and CK18. Myoepithelia express smooth muscle actin (α-SM actin), p63, and CD10 (Fig. 13.1). Apart from very rare exceptions (microglandular adenosis and syringomatous adenoma of the mammilla), all benign proliferative lesions mimic the normal glandular epithelium. Side-by-side, these lesions contain CK5/14-positive progenitor cells (CK5/14+), glandular cells (CK8/18+), and/or myoepithelial cells (CD10+, α-SM actin+, etc.), and this can be demonstrated by immunohistochemistry. Another important component of benign lesions is the stroma with its extracellular matrix; it is present not only in fibroadenomas, but also in papillomas, adenomas, radial scars, sclerosing adenoses, etc. Recently, it was found that the interactions seen between the epithelium and stroma of benign proliferative lesions are similar to those seen during the normal developmental process of the mammary gland (Osin et al, 1998; Boecker et al, 2006). In summary, these findings show that simple epithelial hyperplasia is a benign lesion and is completely unrelated to carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. The traditional view of breast cancer development has assumed a linear development, with the simple epithelial hyperplasia being the initial lesion that develops into atypical ductal hyperplasia, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and finally, invasive mammary carcinoma (Boecker et al, 2001). This hypothesis has been challenged by a series of recent findings. Thus, ductal hyperplasia of usual type (HUT) and DCIS/invasive carcinoma show basic genetic differences (e. g., in the comparative genomic hybridization [CGH] analysis) that make a transformation from ductal hyperplasia to neoplasia unlikely (Buerger et al, 1999, 2001; Farabegoli et al, 2002). This is also demonstrated by basic differences in the immunohistochemical expression of the markers listed above. In contrast to benign proliferative lesions with a mixture of cells from normal tubules, most carcinomas have a strictly glandular phenotype. More than 97% of in situ lesions and approx. 90% of invasive carcinomas are CK8/18+ (Fig. 13.2). Most mammary carcinomas develop de novo from the glandular epithelium of the terminal ductal-lobular units (TDLUs). Development of lobular and/or ductal neoplasia in situ within primarily benign epithelial proliferative lesions is relatively rare. The diagram shown in Fig. 13.3 reflects the current state of knowledge regarding breast cancer development. Thus, the majority of benign proliferative mammary gland lesions may be interpreted as proliferative lesions that represent a developmental “cul-de-sac” and are therefore unrelated to carcinogenesis. Fig. 13.2 Invasive carcinomas positive for CK8/18. Fig. 13.3 Hypothetical model of breast cancer development. The progenitor cell concept not only contributes to the basic understanding of the pathogenesis of benign and malignant lesions, but it is also becoming a valuable diagnostic aid. The detection of cellular components that correspond to those of a normal tubule allows for the classification of a proliferative lesion as definitely benign. However, when a lesion is comprised exclusively of differentiated glandular cells, this strongly suggests a precancerous lesion or carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry. In difficult cases, the pathologist may use immunohistochemistry for histologic pattern recognition in addition to conventional histology with routine staining. Based on the progenitor cell concept, immunohistochemistry is used to analyze the cellular constituents of the lesions even when this is not possible with conventional histology. This method thus provides the key for making a correct diagnosis. Breast pathology preferentially uses antibodies directed against basal cytokeratins (CK5, CK14) and luminal cytokeratins (CK8, CK18), as well as smooth muscle (SM) proteins as myothelial markers (e. g., α-SM actin, calponin, maspin, myosin heavy-chain [SMMHC], CD10, and p63). Whereas benign proliferating lesions are characterized by a mixture of different cellular constituents, precancerous lesions and invasive carcinomas are composed of just one cell type. Table 13.1 lists the lesions in question and cell type-specific marker proteins. Carcinomas of the luminal type (CK8/18+) represent more than 90% of breast carcinomas found. Basal cell carcinomas, which represent a small percentage of breast carcinomas, were described more than 20 years ago (Nagle et al, 1986; Wetzels et al, 1989). Ever since its description in the journal, Nature, by Perou et al (2000), this type of breast cancer has been the center of today’s breast research (Abd El-Rehim et al, 2004; Jacquemier et al, 2005; Korsching et al, 2008; Livasy et al, 2006; Sørlie et al, 2001). These basal cell carcinomas express CK5 and CK14, which should be taken into account when interpreting CK5/14 immunohistochemistry. Normally, CK5/14+ cells are characteristic for benign proliferative lesions and are distributed in a mosaic-like fashion. In basal cell carcinomas, these cells occur as homogenous (monotonous) clonal cell populations and exhibit distinct cytologic signs of malignancy. Qualification of the pathologist. CNB diagnosis demands far more from the pathologist than the diagnosis of excision (open surgical) biopsy. A decision on patient management is based on the pathologic findings from quantitatively limited material; however, communicating the results in an interdisciplinary context is much more demanding. Although the pathologic result is exclusively based on tissue samples, the pathologist must nevertheless assume that the biopsy may contain only parts of the target lesion. Experience and training for examining CNBs as well as excision biopsies are required for optimal pathologic diagnosis. Furthermore, the pathologic findings are correlated with those of mammography, US, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Hence, the pathologist should also have a basic knowledge of diagnostic imaging. Specialization in the field of breast diagnosis thus seems to be essential. Nevertheless, the pathologist can only meet the special demands of CNB when the minimum requirements on patient information and handling of biopsy specimens are fulfilled. Accompanying information. Interpretation of the histopathologic results of a CNB is best achieved when the pathologist has detailed knowledge about the indication and biopsy method used, as well as the target lesion characteristics. Detailed information on clinical findings, mammography, US, and other imaging results are absolutely essential. The situation is optimal when the corresponding images are all available. Table 13.2 lists the minimum information required for the pathologic examination of specimens obtained from a CNB.

Requirements for Pathologic Diagnosis

Progenitor Cell Concept

Diagnostic Implications of the Progenitor Cell Concept

Requirements for Optimal Pathologic Diagnosis of Biopsy Specimens

Question | Marker proteins | Remarks |

Hyperplasia of usual type or ductal and lobular neoplasia | CK5/14 and CK8/18 | CK5 and/or CK14 or CK8/18 mosaic is typical for HUT, whereas neoplasia in situ* is CK5- and/or CK14-negative |

Sclerosing adenosis classic tubular carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) or | α-SM-actin, CD10, calponin, p63, SMMHC, maspin, CK5/14 | Loss of myothelial cell layer in carcinomas Carcinomas are p63-negative and CK5- and/or CK14-negative |

Papilloma or papillary carcinoma | α-SM-actin, CD10, calponin, p63, maspin, CK5/14 | Myothelial cell layer is present in papillomas, but usually absent in carcinomas For exceptions, see below† |

Squamous epithelial differentiation | CK6, 10, 11 | Sensitive markers for squamous epithelial differentiation |

Adenomyothelial tumors or phyllodes tumors and spindle cell lesions | CK5/14, α-SM-actin, CK8/18 | Note that all markers are expressed in adenomyothelial tumors Tumors of mesenchymal origin are usually CK5- and/or CK14-negative The mesenchymal portion of phyllodes tumors is CK5- and/or CK14-negative |

Tubular carcinoma and other G1 and G2 carcinomas, as well as most G3 | p63, α-SM-actin, CD10, calponin, CK5/14, CK8/18 carcinomas | With few exceptions,* carcinomas are negative for these markers Note that myofibroblasts stain intensely for α-SM-actin |

† Some papillary carcinomas in situ contain a fully developed myothelial cell layer.

Patient data | Surname First name Date of birth |

Biopsy localization | Left/right side Time, distance from the nipple Region (subregion according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology [ICDO]: quadrant, central glandular body, axillary process) |

Clinical examination | Palpation Inspection Findings on skin and nipple Relevant patient history and family history |

Findings of imaging | Mammography (focal lesion, architectural distortion, microcalcification) US MRI BI-RADS category |

Size of lesion | Maximum diameter in mm, with indication of method |

Differential diagnosis | With indication of method |

Overall clinical and image assessment | Suspected grade (for scoring, see text) |

Yield of tissue | Number of specimens obtained |

Results of specimen radiography | Number of samples containing microcalcification |

Handling of specimens after biopsy. The specimen capsules must be moved with small forceps using great care to prevent fragmentation and artifacts due to squeezing. All specimens obtained during the biopsy of microcalcification lesions must undergo specimen radiography. This is the only way to start a targeted histologic search for microcalcification. For this purpose, the microcalcification-containing specimen capsules are separated from the others and submitted for pathologic examination together with the specimen radiographs. Ideally, the radiologist has already placed the specimens in special tissue-embedding cassettes for histologic processing. Buffered 4% formaldehyde should be used for fixation.

Tips and Tricks

Fixation should be performed as quickly as possible to prevent irreversible artifacts by air-drying. The specimens should be moistened with physiologic saline when they cannot be placed directly into the shipping container after biopsy (e. g., prior to specimen radiography after VAB).

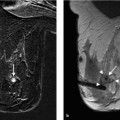

Histotechnical processing. Examination of frozen sections of CNB tissue is risky and unnecessary; it should be avoided (Step 3–Guideline for Early Detection of Breast Cancer in Germany; Leitlinie Brustkrebs-Früherkennung in Deutschland, 2008; HeywangKöbrunner et al, 2003; Ellis et al, 2004). The emotional stress caused by waiting for the results from regular histologic sections, which is occasionally cited as justification for frozen sections, can certainly be reduced by appropriate patient education and optimal interdisciplinary time management. This is true especially in modern breast diagnostics where suspicious, but usually benign lesions dominate. The minimum time for optimal tissue fixation is 6 hours. Shorter fixation times lead to reduced quality of the conventional histologic diagnosis (e. g., when grading the lesions; Start et al, 1991) and of the immunohistochemical examination (Cattoretti, 1994), particularly when a diagnosis involves the detection of estrogen receptor (ER) and human epithelial growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (Goldstein et al, 2003). This should also be taken into account when planning rapid embedding programs. After fixation, the tissue samples should be embedded in paraffin in a horizontal position (Fig. 13.4) and poured into paraffin blocks. No more than four specimens should be placed into one embedding cassette (Wells et al, 2000). Microtome sections of a maximum 4 μm in thickness are best. The number of sections or sectioning levels depends on the target lesion. Although in theory, a single section may suffice for the diagnosis of a focal lesion, most laboratories dealing with early detection diagnosis prepare sections from three sectioning levels for focal lesions and architectural distortion. If microcalcifications are the biopsy target, sectioning levels are obligatory. This approach has found its way into international and national guidelines (HeywangKöbrunner et al, 2003; Ellis et al, 2004; Wells et al, 2006b; Stufe-3-Leitlinie Brustkrebs-Früherkennung in Deutschland, 2008). The first section should be used for examination to prevent loss of calcification.

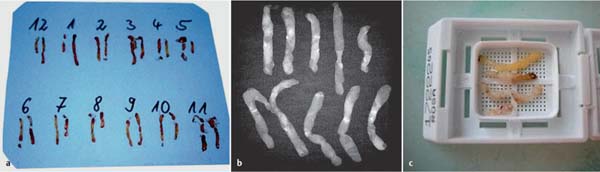

Fig. 13.4a–c Paraffin embedding of tissue samples.

a Samples arranged in the order of 1 to 12.

b Part of a specimen radiograph.

c Samples placed in an embedding cassette.

B Categories

The simple classification of CNB findings into histologically benign or malignant lesions no longer accommodates the diagnostic and management problems in modern breast cancer diagnosis. Individual lesions differ greatly in their clinical importance, and there is a wide scope of further diagnostic and therapeutic options. The suggestion of expressing the pathologic findings of biopsies in categories stems from mammographic screening programs. In 1997, the B categories for breast CNBs were introduced in the UK for the first time by the National Coordinating Group for Breast Screening Pathology (National Coordinating Group for Breast Screening Pathology, 1997). These categories were then adopted by the European guidelines for mammographic screening (European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, 2001). Their use has now extended outside the screening setting, and they are recognized internationally.

Five categories. The five-category classification system (Table 13.3) helps the pathologist to formulate the biopsy assessment to facilitate a decision on further management.

Importance of the B categories. The categories permit a clear statement regarding the diagnosis after CNB. It is not always possible to establish a definitive histologic diagnosis; nevertheless, the histopathologic results as documented are often used in further decisions. In most cases, the results are either benign (B2) or malignant (B5). In the remaining cases, the biopsies are either normal or unsatisfactory (insufficient amounts of tissue) (B1), of uncertain malignant potential (B3), or suspicious of malignancy (B4). The B categories are also used as a basis for standardized quality assurance (see the section, Quality Indicators of the Pathologic Diagnosis, p. 196). This requires that the B categories be derived exclusively based on microscopic findings, without influence from any information derived from imaging and clinical findings. In an interdisciplinary conference between the patholo-gist and clinician, correlation between the pathologic and image findings is confirmed. The procedural consequences are the result of this analysis. When using the B categories, it is essential that the pathologist strictly applies the definitions as provided in his or her country’s accepted guidelines.

Category | Definition |

B1 | Normal tissue / unsatisfactory biopsy |

B2 | Benign lesion |

B3 | Lesion of uncertain malignant potential |

B4 | Lesion suspicious of malignancy |

B5 | Malignant lesion |

B5a | DCIS |

B5b | Invasive carcinoma |

B5c | Invasion not assessable |

B5d | Other malignant lesion |

B1—Normal Tissue/Unsatisfactory Biopsy

This category includes biopsies with normal tissue as well as biopsies unsatisfactory for evaluation. Biopsies unsatisfactory for pathologic evaluation contain insufficient amounts of tissue and/or are comprised predominantly of blood clots or show severe artificial alterations. The pathologic report should always state the reason for classification as B1.

If the tissue is normal, the report should distinguish biopsies containing glandular tissue from those without parenchyma. Minor pathologic changes at the microscopic level, which are unlikely to show up on the radiograph, should be classified as B1. Lesions with microcalcifications of < 80 μm should also be classified as B1.

A B1 result with normal tissue is an indication that the target lesion may not have been hit. But this is by no means the only explanation. The normal glandular tissue may be part of a hamartoma, and normal fatty tissue may be part of a lipoma. Islets of normal parenchyma in a mostly involuted breast may cause small dense areas on the mammogram.

Conclusions. Category B1 largely includes biopsies that do not represent the target lesion, but this does not necessarily apply to all biopsies classified as B1. Some B1 biopsies do correlate with the lesion to be examined and thus permit a diagnosis. Such a connection must then be definitively confirmed or excluded by radiologic–pathologic correlation.

B2—Benign Lesion

This category implies that the biopsy contains a benign lesion that, in principle, may have been responsible for the results in the mammogram, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Whether this holds true for the case in question will have to be clarified by the subsequent radiologic–pathologic correlation. In cases of doubt, minor pathologic changes should be classified as B1 instead.

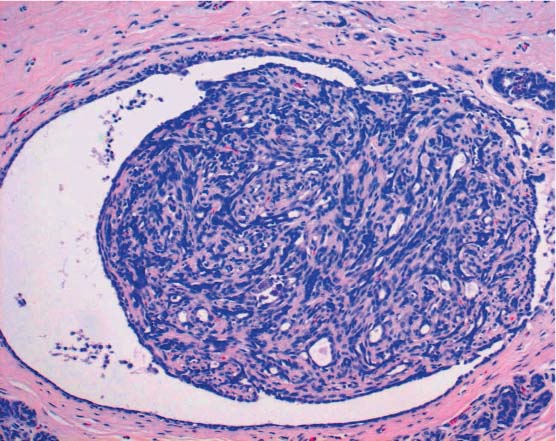

Typical lesions. Typical B2 lesions include fibroadenomas, sclerosing adenoses, blunt duct adenoses, periductal mastitis, micro-cysts, macrocysts, abscesses, and fatty tissue necroses. Apart from fibroadenomas and macrocysts, almost all of these lesions may also occur as a minor microscopic lesion of a few hundred micrometers in diameter, thus calling for classification as B1. In some cases, unambiguous diagnosis of a hamartoma in the CNB specimen is nevertheless possible, thus qualifying the lesion for category B2. In some cases, it is even possible for the pathologist to confirm that a papilloma is completely contained in the biopsy specimen. In that case, the lesion is classified as B2, although it would otherwise be assigned to category B3 (Fig. 13.5).

Fig. 13.5 Papilloma, category B2. Microcyst containing a papilloma of 1.5 mm in diameter, completely included within the biopsy specimen.

Conclusions. Category B2 contains only lesions that are definitely benign according to histopathologic criteria, even though this classification is based exclusively on the microscopic findings. However, assignment of the biopsy to category B2 does not complete the diagnosis of a lesion detected by imaging; a definitive diagnosis is only possible after radiologic–pathologic correlation.

B3—Lesion of Uncertain Malignant Potential

This category includes lesions where the biopsy specimen does not meet the criteria for malignancy, but rather indicates a risk of associated malignancy. Although some of the lesions in this group are known markers for an increased risk of bilateral and diffuse breast cancer later in life, a classification of B3 signals a synchronous and local risk at the time of biopsy and in the immediate surrounding of the biopsy site.

Typical lesions. Category B3 consists basically of two groups:

lesions with a known heterogeneous structure, the clinically relevant portion of which may not have been hit by the biopsy

lesions with a known heterogeneous structure, the clinically relevant portion of which may not have been hit by the biopsy

lesions that frequently occur together with intraductal or invasive carcinomas

lesions that frequently occur together with intraductal or invasive carcinomas

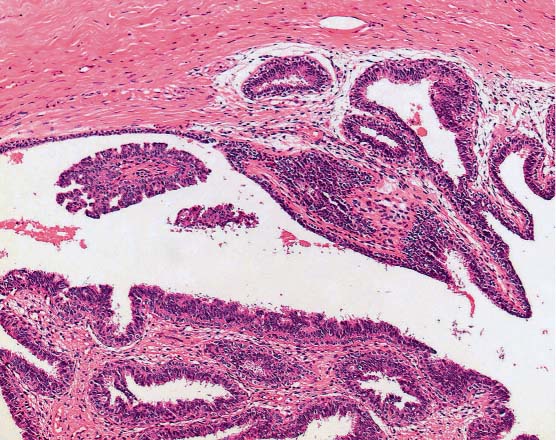

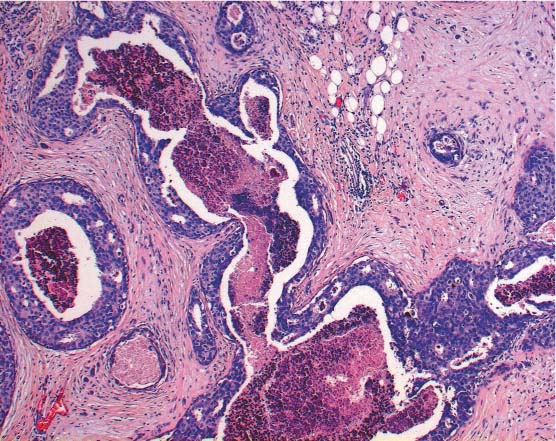

The first group (heterogeneous lesions) includes papillary lesions (Fig. 13.6) (unless they are completely contained in the biopsy specimen and classified as B2, see above), radial scars, phyllodes tumors, mucocele-like lesions, cystic hypersecretory lesions, and spindle cell proliferations. In the case of these lesions, it is possible that a malignant portion remains in situ because of the limited amount of tissue removed by CNB.

The second group (high-risk lesions preferentially associated with intraductal or invasive carcinomas) includes lobular neoplasia (LN; except special cases listed under B5a), flat epithelial atypia, and atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH).

Conclusions. Diagnostic excision is by far not the only conclusion for category B3. As with other B categories, the conclusion depends on the radiologic–pathologic correlation. The various combinations of specific histologic findings and the findings of diagnostic imaging after biopsy will determine the next approach (see the section, Radiologic–Pathologic Correlation, p. 188).

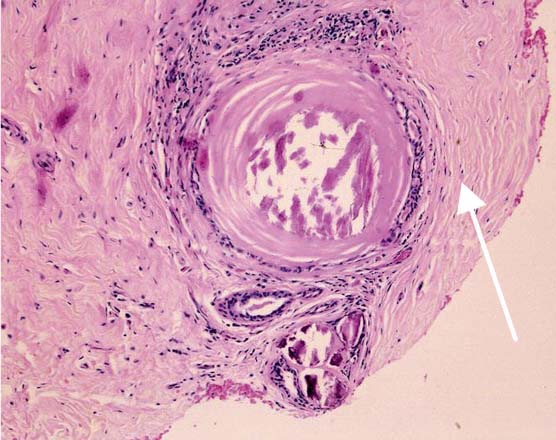

B4—Lesion Suspicious of Malignancy

Due to technical problems during the biopsy procedure, not enough tissue of the target lesion may have been obtained. This may lead to a situation where a definitive histologic diagnosis is not possible; nevertheless, the lesion is clearly abnormal and suspicious of malignancy (Fig. 13.7). A similar situation may arise due to artifacts, such as squeezing, air-drying, or insufficient fixation.

Conclusions. Category B4 does not provide a basis for therapeutic decisions. Lesions of this category do not necessarily require clarification by excision biopsy. Any further approach should be determined by the interdisciplinary team after analyzing what has led to the B4 classification.

Fig. 13.6 Papillary lesion. Cross-section of a dilated duct with part of a benign papilloma.

Fig. 13.7 Suspected malignant lesion, category B4. Non-high-grade atypical cell clusters in minute amounts near an intraductal calcification (arrow). Intraductal neoplasia is suspected. However, the findings do not allow a definitive diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree