Etiology

The presence of extraluminal air in an acutely ill patient with abdominal pain is an ominous sign that usually indicates perforation of a hollow viscus. Common causes include gastroduodenal peptic ulcer disease, perforation of a gastrointestinal neoplasm, acute appendicitis with perforation, and acute colonic or (less often) small bowel diverticulitis, including Meckel’s diverticulitis. Other considerations include iatrogenic perforations caused by catheters or endoscopes, perforations caused by foreign bodies, or spontaneous rupture of the distal esophagus (Boerhaave’s syndrome), as well as ischemia leading to necrosis and resultant loss of bowel wall integrity.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The epidemiology of hollow viscus perforation depends on the underlying cause. Although the prevalence of the various causes varies greatly, the morbidity and mortality of hollow viscus perforation are significant in all cases, given the possibility of progression to peritonitis and its resultant complications.

The most common cause of hollow viscus perforation is gastroduodenal peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease is exceedingly common, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 10% in the United States. The incidence of perforation has been reported to be 2% to 5% in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Perforated peptic ulcer disease carries significant morbidity and mortality. Overall postoperative mortality has been reported to be 19% but exceeds 40% in patients older than 79 years of age.

A second common cause of nontraumatic hollow viscus perforation is perforated colonic diverticulitis. The prevalence of diverticulosis is significantly associated with age and is reported to affect 65% of patients older than 65 years of age; 10% to 25% of patients with diverticular disease are reported to develop diverticulitis. Of these, approximately 10% to 15% of patients develop free perforation. Interestingly, the incidence of perforated diverticulitis has been reported to be increasing in certain populations secondary to aging and dietary influences. The mortality of perforated sigmoid diverticulitis has been reported to be approximately 8%.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The epidemiology of hollow viscus perforation depends on the underlying cause. Although the prevalence of the various causes varies greatly, the morbidity and mortality of hollow viscus perforation are significant in all cases, given the possibility of progression to peritonitis and its resultant complications.

The most common cause of hollow viscus perforation is gastroduodenal peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease is exceedingly common, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 10% in the United States. The incidence of perforation has been reported to be 2% to 5% in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Perforated peptic ulcer disease carries significant morbidity and mortality. Overall postoperative mortality has been reported to be 19% but exceeds 40% in patients older than 79 years of age.

A second common cause of nontraumatic hollow viscus perforation is perforated colonic diverticulitis. The prevalence of diverticulosis is significantly associated with age and is reported to affect 65% of patients older than 65 years of age; 10% to 25% of patients with diverticular disease are reported to develop diverticulitis. Of these, approximately 10% to 15% of patients develop free perforation. Interestingly, the incidence of perforated diverticulitis has been reported to be increasing in certain populations secondary to aging and dietary influences. The mortality of perforated sigmoid diverticulitis has been reported to be approximately 8%.

Clinical Presentation

Because the signs and symptoms of hollow viscus perforation are typically related to the underlying cause, there are a variety of clinical presentations. Initially, symptoms will be localized to the area of disease; for example, patients with peptic ulcers may complain of intermittent or constant epigastric pain, sometimes radiating to the back. Although myriad initial clinical presentations exist, once free perforation into the peritoneal cavity occurs, most patients will have generalized peritonitis with peritoneal guarding, shock, and prostration.

Pathophysiology

Anatomic considerations depend on the underlying cause of the hollow viscus perforation. Patients with esophageal perforation typically present with pneumomediastinum, which may dissect into the neck, pleural space, or pericardial space, as well as the retroperitoneum and intraperitoneal cavity. The short, intra-abdominal portion of the esophagus is within the retroperitoneum. The second and third portions of the duodenum, ascending and descending colon (in most patients), as well as the rectum are considered retroperitoneal structures ( Figure 16-1 ). The remainder of the gastrointestinal tract is considered intraperitoneal. Typically, free air will be found within the abdominal cavity containing the portion of the gastrointestinal tract that is perforated. However, air may track within from the peritoneal cavity into the retroperitoneum and vice versa, as well as caudad into the thorax, including the mediastinum and pleural spaces.

In esophageal rupture secondary to Boerhaave’s syndrome there is failure of the cricopharyngeus muscle to relax in coordination with vomiting. The esophageal tears are typically within the posterolateral aspect of the distal esophagus, several centimeters proximal to the gastroesophageal junction. This area has been demonstrated to be an anatomically weak point.

In patients with peptic ulcer disease, the duodenum is more commonly affected than the stomach. Within the duodenum, ulcers are most commonly found within the first portion. Based on preoperative imaging, the sites of gastroduodenal ulcer perforation are typically within the duodenum or are juxtapyloric in location.

In patients with small bowel diverticulosis, the diverticula may be categorized as congenital or acquired. In acquired, or true, diverticula, all three layers of the bowel wall are involved. Like pulsion diverticula elsewhere, acquired diverticula contain protrusions of portions of the bowel wall through an area of focal mural weakness. Meckel’s diverticula are true diverticula in that they contain all three layers of the intestinal wall and arise along the antimesenteric border of the small bowel. They are commonly found 40 to 100 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve, and the length of the diverticulum ranges from 1 to 10 cm in 90% of patients. Colonic diverticula represent pulsion diverticula and present as outpouchings of mucosa, muscularis mucosa, or submucosa through focal weaknesses of the colonic wall.

Pathology

The pathologic findings of hollow viscus perforation depend on the underlying cause. Patients with Boerhaave’s syndrome have a failure of the proper timing of cricopharyngeal relaxation with vomiting. This causes a significant increase in the intraluminal pressures of the esophagus, leading to full-thickness rupture.

In patients with peptic ulcer disease, failure of gastroduodenal mucosal mechanisms secondary to Helicobacter pylori infection, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use, and hypersecretory states, among others, results in a defect in the muscularis mucosa. If the ulceration continues beyond the muscularis mucosa, free perforation of the stomach or duodenum may occur.

In diverticulitis of the small bowel or colon, once the mucosa-lined outpouching through the bowel wall is obstructed, distention results secondary to ongoing secretion of mucus and bacterial overgrowth. Vascular compromise of these mucosal outpouchings may occur, leading to perforation. Similar to the pathophysiology of perforated diverticulitis, appendicitis results from obstruction of the appendiceal lumen with subsequent distention from mucosal secretions. Capillary perfusion pressures are outstripped, and venous and lymphatic drainage is obstructed. The influx of bacteria into the appendiceal wall as well as the decreasing arterial flow and tissue necrosis lead to appendiceal perforation.

In patients with colonic perforation secondary to colorectal carcinoma, the perforation may occur proximal to the tumor, related to obstruction and distention, or occur directly at the site of the tumor. In cases of perforation related to obstruction, the pathophysiology is similar to that of the aforementioned examples of increasing luminal distention and decreasing venous return followed by decreasing arterial inflow, resulting in tissue necrosis and loss of mural integrity. In cases of perforation directly at the site of the tumor, transmural tumor invasion and necrosis are underlying mechanisms resulting in loss of mural integrity.

Imaging

Radiography

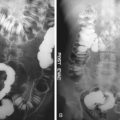

Plain radiography is useful in the initial evaluation of suspected hollow viscus perforation to detect the secondary signs of extraluminal air ( Figure 16-2 ). However, the precise location and underlying cause of perforation are unlikely to be detected with radiography.

Acquisition of both a supine radiograph of the abdomen and an upright view of the chest is performed to evaluate for free intraperitoneal air. Other options include left lateral decubitus views of the abdomen or lateral chest radiographs. Upright radiographs or left lateral decubitus views should be acquired with the central ray of the x-ray beam at the highest level of the peritoneal cavity to increase the sensitivity of detection of intraperitoneal air. Numerous signs of pneumoperitoneum on abdominal radiographs have been described, including Rigler’s sign, in which air is seen on both sides of the bowel wall; the falciform ligament sign, in which air outlines the falciform ligament; the football sign, in which air outlines the confines of the peritoneal cavity; the inverted V sign, in which air outlines the medial umbilical folds; and the right upper quadrant air sign, in which a focal, typically triangular, collection of gas is seen in the right upper quadrant. Visualization of air outlining the median subphrenic space, the so-called cupola sign , has also been described in a minority of patients with pneumoperitoneum on supine radiographs.

Because esophageal rupture as well as dissection of air from intra-abdominal perforations may lead to pneumomediastinum, chest radiography may be employed for initial evaluation. Various radiographic findings have been described, including the visualization of air superolateral to the heart on the left on an upright chest radiograph, lucent streaks of air outlining the aorta or great vessels, the continuous diaphragm sign with air outlining the superior portions of the diaphragm, and many others.

Finally, because hollow viscus perforation may be associated with retroperitoneal air, abdominal radiographs may be useful in the initial diagnosis. Retroperitoneal air may be identified as linear or bubbly lucencies overlying the expected location of the retroperitoneum. Alternatively, air may be seen along fascial planes of known retroperitoneal structures such as the psoas muscles, kidneys and adrenal regions, or muscles of the diaphragm.

Computed Tomography

CT is the most sensitive modality in detecting small volumes of extraluminal air. In cases of hollow viscus perforation, CT has been shown to be highly accurate in the localization of the site of perforation, especially when thin collimation images and multiplanar reformatted images are viewed. The findings of focal bowel wall thickening, localized air bubbles, and direct visualization of a rent within the wall of the bowel have been shown to be accurate predictors of the site of perforation.

Findings of esophageal rupture on CT include pneumomediastinum, periesophageal fluid, and esophageal thickening, as well as the possibility of direct visualization of the esophageal rent.

CT findings in patients with perforation related to peptic ulcer disease include extraluminal gas as well as extravasation of oral contrast media ( Figures 16-3 and 16-4 ). In addition, focal thickening of the gastrointestinal tract about the site of perforation as well as inflammatory stranding of the adjacent abdominal structures may be seen.