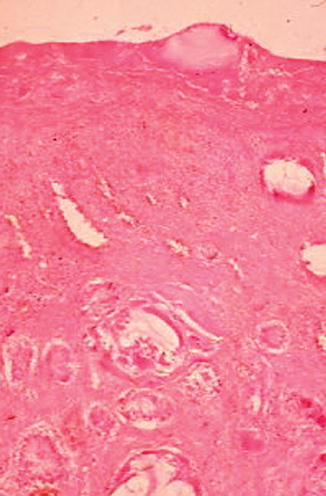

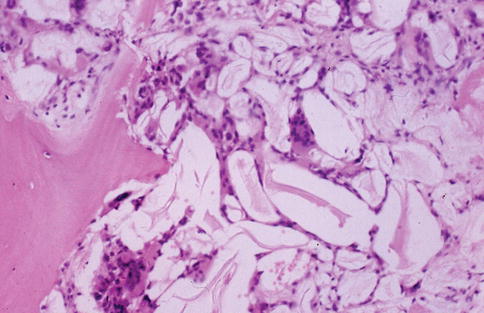

Fig. 9.1

Cyst removed from a vertebral body

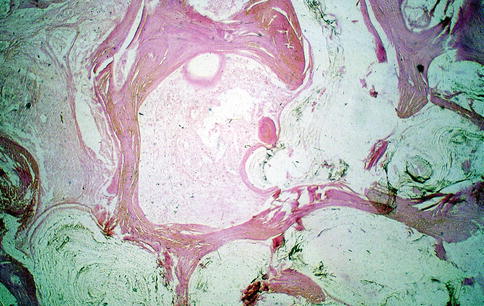

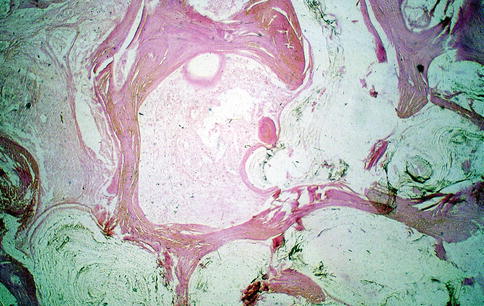

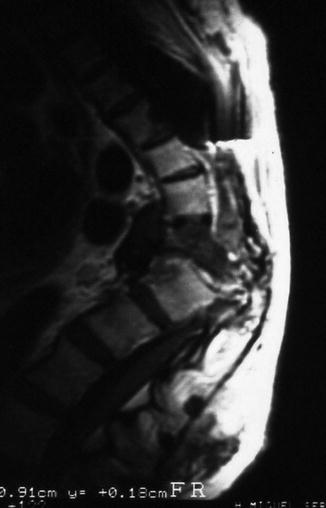

Fig. 9.2

Large open cyst with multiple daughter vesicles inside

The clear, yellow hydatid fluid contains sodium chloride, proteins, lipids, polysaccharides, and ions, having a neutral pH. Breakage of a cyst can trigger an immunological reaction from the host, sometimes leading to an anaphylactic shock. Severe bone necrosis and inflammatory reaction may appear if bone lesions become infected, forming granulomas made up of lymphocytes, eosinophils, polymorphonuclears, and giant cells. Differential diagnosis with granulomatous infections might be very difficult.

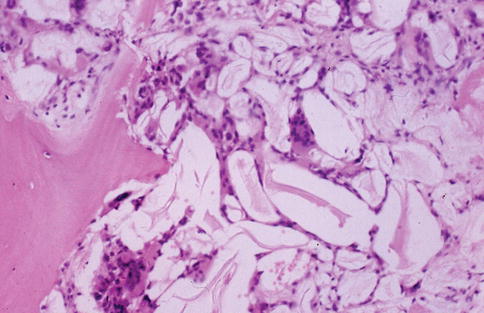

Up until now it has been thought that disc space act as a barrier against infection. Colonization of several spinal levels at the same time, or spreading under the longitudinal ligaments from one vertebral body to the contiguous one, could explain the cases involving several spine levels. Nevertheless, Karantanas et al. (2003) have described a case of echinococcosis with cystic involvement of the disc space. Based on our experience with the hip joint, as well as the spread of the disease across the joint into the rib, our view is that the cartilage tissue is not an insuperable barrier against hydatid disease and parasite invasion through the joint surface is possible (Fig. 9.3).

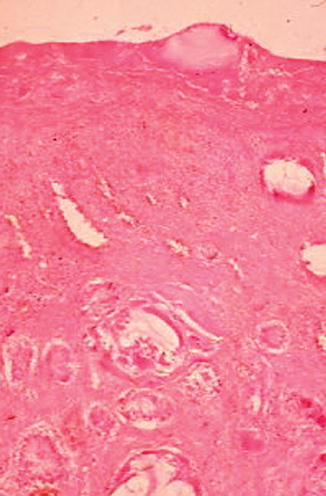

Fig. 9.3

Fibrous tissue on the surface of a femoral head. Hydatid membranes have replaced the cartilage

Bone cysts expand slowly and usually have a multilocular growth. Enlargement is achieved by local erosion of bone, and the pressure on the blood vessels of the marrow bone may result in a vascular necrosis (Fig. 9.4). Since trabecular destruction is complete (Fig. 9.5), infestation progresses toward the cortical bone and can spread through the anterolateral paravertebral area or into the spinal canal. Computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may then show a pseudo-abscess (Fig. 9.6), and a differential diagnosis with spinal tuberculosis or vertebral pyogenic osteomyelitis is sometimes difficult.

Fig. 9.4

Devitalized, eroded bone trabeculae by the growth of cysts

Fig. 9.5

Hydatid membranes with a giant-cell reaction next to an unstructured bone trabeculae

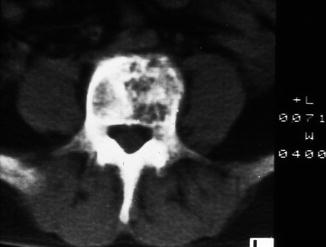

Fig. 9.6

CT: vertebral hydatidosis with large pseudo-extravertebral abscess

Mechanical failure of the vertebrae can lead to compression fractures, even if cortical bone is preserved. The progression of the infection could lead to angular kyphosis and neural compression of the spinal cord (Fig. 9.7). In other cases, in which the infection progresses through the pedicles, the intervertebral foramina may be affected, and root compression symptoms could be present.

Fig. 9.7

Total destruction of two vertebrae producing severe kyphosis and cord compression

In this respect, the understanding of the mechanical strength properties of the vertebrae is necessary. Although the cortical bone is more resistant, cancellous bone plays a major role in the global mechanical strength of the spine, since its trabecular struts act as the internal scaffolding of the vertebral body. The damage to the cancellous bone leads to a loss of rigidity and to an initial loss of vertebral body height. If this damage progresses, the cortical bone remains as an empty eggshell, and it is not capable to withstand compressive loads, leading to a compression fracture (Fig. 9.8). If the infection involves also the cortical bone, the loss of resistance and the risk of fracture are then increased.

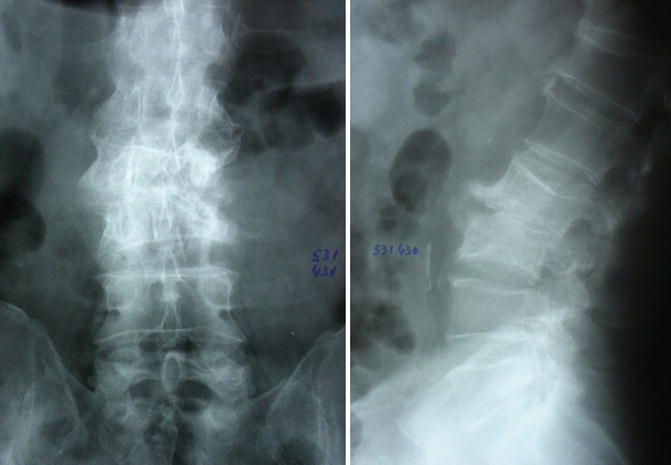

Fig. 9.8

Radiographic tomography: lumbar hydatidosis simulating a vertebral compression fracture

Clinical Presentation

Since 1807, when Chaussier described the first case of vertebral infection, there is a lack of published papers detailing accurately the clinical presentation of vertebral echinococcosis. This may be due to the unspecific presentation of the hydatid disease in the bone and to the long clinically silent period before the first symptoms (up to 40 years in some cases) (Murray and Haddad 1959; Zlitni et al. 2001; Song et al. 2007; Papanikolaou 2008). Echinococcosis in general, and that involving the spine in particular, is an adult disease, partly due to this long silent period. The youngest patient admitted to our service was 24 years old at the time of diagnosis, and the oldest one was 77 years old, with an average of 51.3 years at presentation.

Back pain is the most typical symptom of spinal hydatidosis, frequently associated with neurological deficits. Trabecular and cortical bone are progressively destroyed as bone cysts expand, and vertebral compression fractures may appear. An angular kyphosis could be present especially when several levels are affected. In severe cases, bone sequestrums extruded into the spinal canal from vertebral bodies cause neural compression. Neural compression can also be produced by cysts invading the extradural space. Usually, both facts (extradural cystic invasion and destruction of the vertebral body) are present when echinococcosis brings about neurological deficits.

If infection progresses through the vertebral pedicles, involving the foramina, root compression symptoms could appear. When the hydatid cysts destroy the anterior vertebral cortex, the infection spreads through the anterolateral vertebral area. In these cases, the appearance of a pseudo-abscess may resemble a pyogenic osteomyelitis or a granulomatous infection such as spinal tuberculosis.

Back pain is associated with vertebral collapse and compression fractures, occurring when the vertebral destruction is advanced. Pain is typically severe at the thoracic and cervical levels and mild at the lumbar and sacral segments. All the patients treated in our hospital service reported moderate to severe back pain for several weeks. Neurological symptoms were present in a high percentage of cases at the time of diagnosis.

In our experience, the clinical course is relatively fast since pain appears, and a worsening of the symptoms coincides with the onset of neurological deficits in a high percentage of cases. The most frequent presentation is a spinal cord compression associated with paraplegia or tetraplegia. Another type of neurological complaint is a root compression syndrome with severe pain and sensory and motor deficits or sphincter dysfunction, depending on the level affected.

Superinfection of the hydatid lesion is possible, but it is not as frequent as other complications. If this happens, a large abscess may spontaneously drain to the surrounding tissues or outside the body, as we have seen in two cases. The course of sacrum involvement is usually asymptomatic, and in some cases, posterior soft tissues or retroperitoneal invasion may be present without previous neurological complaints. Two of our patients initially presented with a posterior sacral tumor and rectal symptoms as the early presentation of hydatid disease of the lower spine (Fig. 9.9).

Fig. 9.9

Sacral hydatidosis with both extra- and intravertebral extensions

In conclusion, the clinical presentation of vertebral echinococcosis is totally unspecific and hardly suggests the diagnosis. Unfortunately, a progressive and severe back pain and the onset of neurological deficits are very common.

Complementary Tests

Imaging

Emergence of new imaging technologies has improved the diagnostic means of vertebral hydatidosis. CT was not available until the 1980s in our hospital, and MRI was first used at the end of the same decade. MRI is the most reliable and useful method for diagnosis (Fahl et al. 1994; Işlekel et al. 1998; Singh et al. 1998) because it allows an excellent visualization of soft tissue injuries. Three-dimensional CT scan (3D CT) was also a breakthrough in identifying lesions and depicting its topography. Another technique ready to use is ultrasound, which has been applied to guide punctures of extravertebral injuries. But we consider most reliable, for this purpose, the CT-guided needle.

Taking advantage of modern methods of diagnosis, Braithwaite and Lees, in 1981, established five sets of column hydatid lesions which can lead to neurological problems: (a) primary intramedullary cyst, (b) intradural extramedullary cyst, (c) extradural intraspinal cyst, (d) hydatid disease of the vertebra, and (e) paravertebral hydatid disease. Currently, this classification is accepted by all the authors.

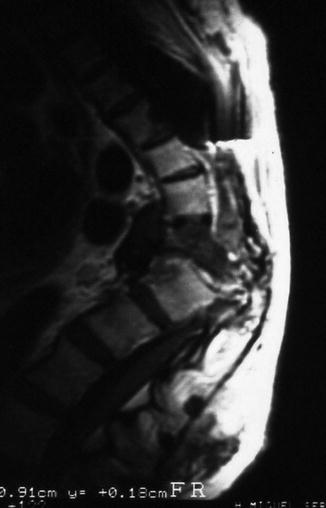

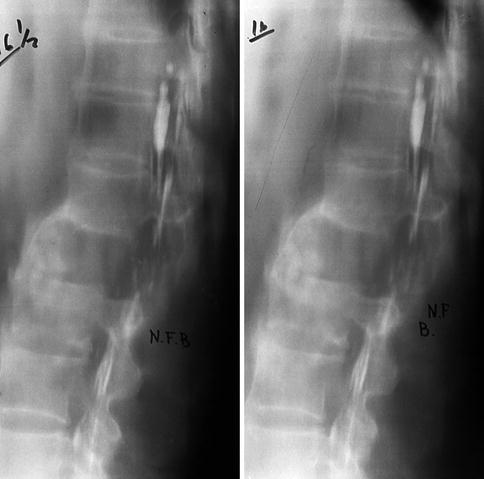

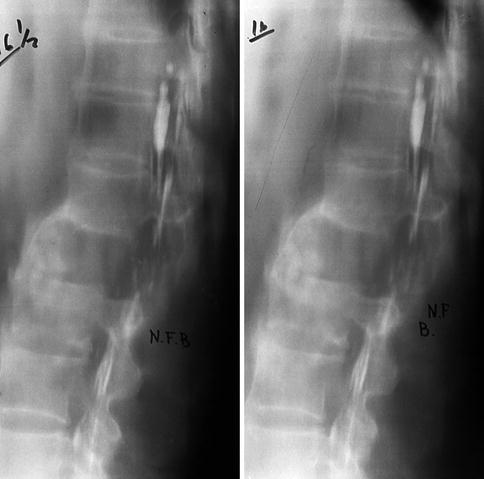

Our early experience with patients suffering from spinal hydatidosis began in the 1970s. At that time, the techniques at our disposal to diagnose neurological injuries were limited to conventional radiology and X-rays with contrast media (Fig. 9.10).

Fig. 9.10

Radiograph with contrast media

Images provided by conventional radiology are quite unspecific. Extensive osteolytic lesions affecting a vertebral body (Fig. 9.11) or the sacrum (Fig. 9.12) may be confused with tumor pathology. Likewise, plain radiography of a crushed vertebral body (Fig. 9.13) may lead to the suspicion of a neoplastic etiology. In other cases, X-rays might suggest an infection of the spine, faced with reactive lesions simulating a vertebral osteomyelitis (Fig. 9.14). Only few skilled orthopedists or radiologists can suspect a hydatid injury on the basis of an X-ray, such as the case shown in Fig. 9.15, in which the diagnosis was suspected from an X-ray appearance showing little bony sequestrum, intervertebral disc integrity, and irregular osteolytic areas.

Fig. 9.11

Cervical hydatidosis: osteolysis of C3

Fig. 9.12

Sacral hydatidosis: osteolytic lesion

Fig. 9.13

Lumbar hydatidosis can be mistaken for tumor etiology

Fig. 9.14

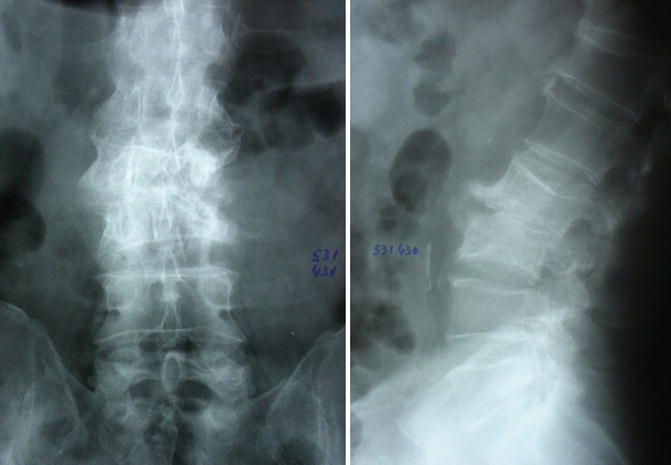

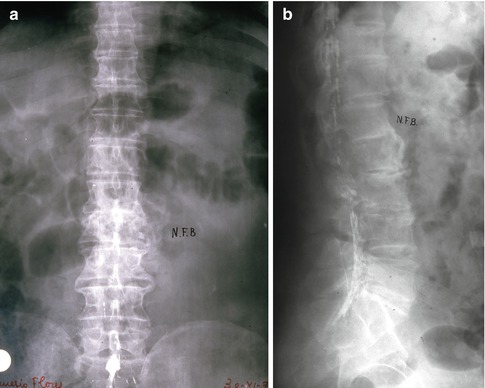

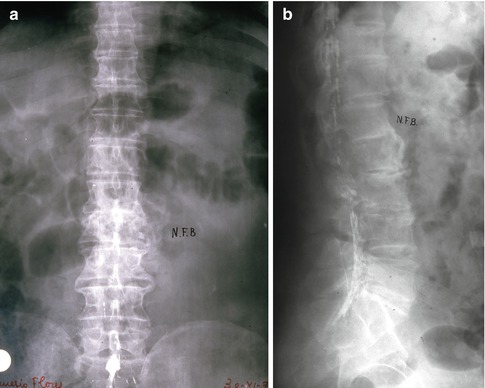

(a, b) Radiographs of a lumbar hydatidosis can resemble a vertebral osteomyelitis

Fig. 9.15

(a, b) Lumbar hydatidosis

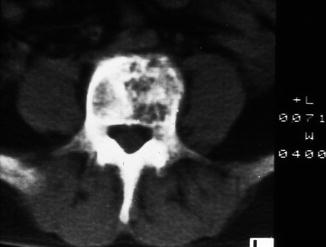

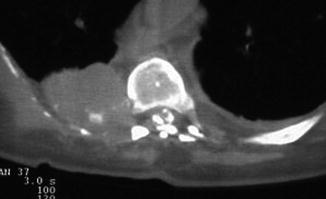

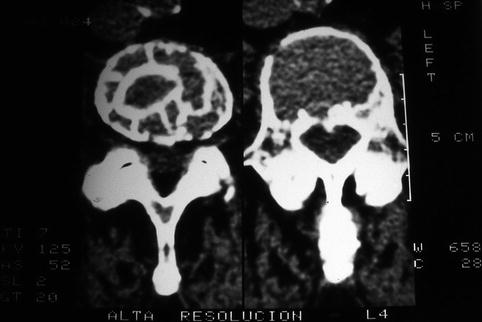

Radiographic tomography allows a more accurate identification of bone lesions. But its resolution is only slightly better than the X-ray; therefore, a tumor etiology is suspected in most cases. The introduction of CT scan in 1984 represented an inestimable help. It allowed us to establish which lesions are characteristic of hydatid disease in the vertebral body (Fig. 9.16): lytic lesions encircled with mild sclerosis, small bony sequestrum, and destruction of the cortex of the vertebra. In other cases, one may find an invaded spinal canal and vertebral pedicle destruction (Fig. 9.17) or small calcifications inside a lesion, which are typical of hydatid disease. The discovery of evident extravertebral, anterolateral lesions (Fig. 9.18), simulating a paravertebral abscess, should suggest a hydatid disease if they have a slight peripheral calcification. Other extra-spinal lesions can be located behind the spine (Fig. 9.19), resting on the rear face of the vertebral lamina. Sometimes, bony sequestrum fragments from the vertebral body might be seen occupying the spinal canal (Fig. 9.20). But most of these images can mislead to an infectious or tumor pathology. Therefore, knowledge of history, clinical signs, and laboratory tests of each patient must be the first step of the diagnostic process. CT scan may also lead to a false diagnosis in the cases when bone lesions resemble a neoplasm (aneurysmatic bone cysts) (Fig. 9.21). In short, CT scan has been a major contribution to the diagnostic process, but it should not be regarded as an infallible technique (Torricelli et al. 1990).

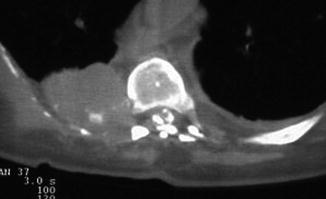

Fig. 9.16

CT: typical lesions of vertebral hydatidosis

Fig. 9.17

CT: pedicle destruction and invasion of the spinal canal

Fig. 9.18

CT: hydatid pseudo-abscess with peripheral calcification

Fig. 9.19

Hydatid cysts on the rear face of a vertebral lamina

Fig. 9.20

Sequestrum fragments from the vertebral body occupying the spinal canal

Fig. 9.21

CT: hydatid cyst simulating a vertebral aneurysmatic bone cyst

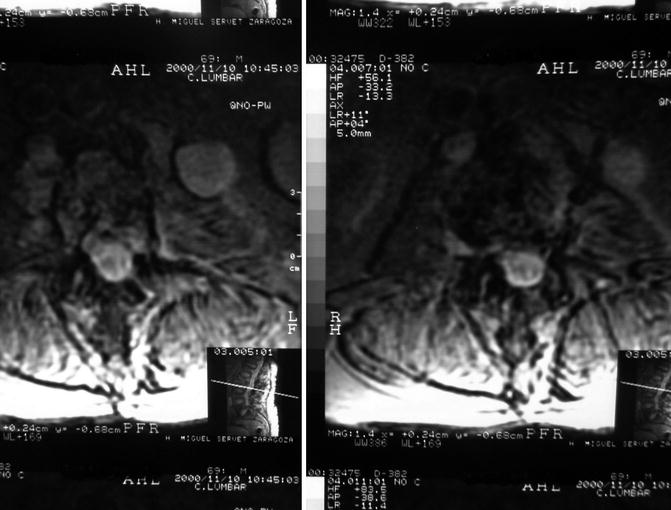

MRI and 3D CT scan allow a more refined diagnosis, particularly in the hands of a radiologist skilled in this disease and if one works in an area where vertebral hydatidosis is not unknown. MRI provides detailed pictures of both soft tissue and bone lesions. This technique usually gets an accurate identification of extravertebral cysts (Fig. 9.22), intravertebral lesions (Fig. 9.23), and extradural intraspinal cysts (Fig. 9.24). Sometimes, images may suggest a wrong infectious etiology. Careful observation will help rule out a septic origin, based on the disc integrity and vertebral body images (Fig. 9.25). Another MRI possibility is the supervision of injuries evolution in patients undergoing medical or surgical treatment (Doganay and Kantarci 2009) (Fig. 9.26). 3D CT scan is another important aid in the diagnostic process, contributing to an accurate knowledge of the topography of the lesion (Fig. 9.27) and helping to determine the lesions etiology.

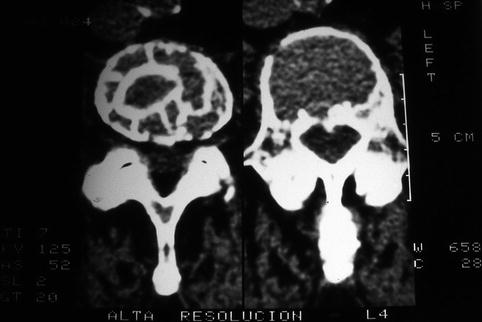

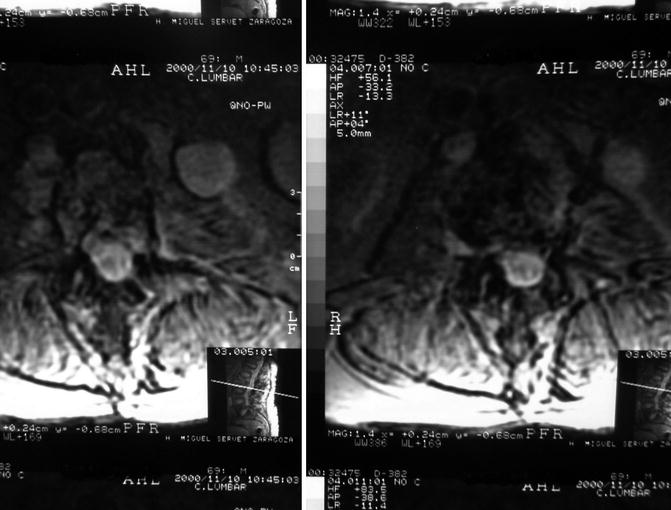

Fig. 9.22

MRI: extravertebral hydatid cysts in a lumbar hydatidosis

Fig. 9.23

Hydatid disease in a vertebral body: MRI images of thoracic spine in two planes (a, b)

Fig. 9.24

Extradural intraspinal cysts

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree