Hypopharynx: Developmental Abnormalities

KEY POINTS

- Imaging may make a precise diagnosis in these anomalies.

- Imaging will often significantly affect medical decision making in these developmental conditions.

- Computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging are typically the main and frequently the only studies required.

- Ultrasound will typically not provide information definitive enough for medical decision making.

In general, developmental abnormalities present during childhood. Some manifest in infancy; however, the presentation is often delayed until sometime beyond infancy, well into the early adult years and even into middle age. If they grow, the growth tends to be at the same rate of normal structures, including a rapid phase at times of accelerated growth of the individual, such as in adolescence. Most, such as hamartomas, tend to grow at the same rate as normal structures. Some, such as high-flow vascular malformations, have internal physiologic dynamics that will allow them to enlarge more rapidly than normal tissues rather than truly proliferate. Truly neoplastic conditions such as teratoma or proliferative hemangioma (Chapters 8 and 9) will manifest growth out of proportion to normal structures.

Developmental abnormalities are frequently discovered incidentally on imaging studies done for other purposes. Some developmental conditions present as masses or because they interfere with function. In the hypopharynx, they would typically manifest with referred otalgia, dysphagia, or odynophagia; the latter two symptoms might manifest as poor feeding in an infant. They are typically not painful unless there is some complicating factor. Developmental abnormalities may also manifest because of such complicating factors. Examples include infection in a branchial cleft or duplication cyst that connects to the hypopharynx; bleeding, thrombosis, or infection of a vascular malformation; or tumor arising in benign ectopic tissue, such as an adenoma or carcinoma in ectopic thyroid tissue and secondarily involving the hypopharynx.

The natural history and imaging appearance of the more common developmental abnormalities that affect the hypopharynx are discussed in dedicated chapters on those topics, including the following:

- Branchial anomalies, such as third and fourth apparatus cysts (Chapter 153)

- Vascular abnormalities (Chapter 9)

- Rarely epidermoids, dermoids, duplications cysts, teratomas, and hamartomas (Chapter 8)

- Thyroglossal duct abnormalities, secondarily only (discussed in conjunction with the larynx in Chapter 202 and the thyroid in Chapter 170)

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

The embryology of some of the conditions that affect the hypopharynx as presented in the introduction of this chapter is summarized in the dedicated chapters on those conditions.

A complete discussion of the cause of conditions typically evaluated by endoscopy is beyond the scope of this text. It is enough to understand that during the prenatal period there is a time when the pharynx must separate from the larynx. The separation process might be incomplete, leaving the two systems connected to some degree and leading to a tracheoesophageal fistula (Fig. 216.1A). Failure of recanalization during this process may result in atresia, stenosis, or web formation. Webs and the more severe anomalies typically will occur in areas that must separate side to side during development, such as the true vocal cords. Failure of obliteration can lead to a persistent posterior laryngeal cleft that causes aspiration in the newborn; this goes to the relationship of the larynx and postcricoid hypopharynx, but it is principally a laryngeal anomaly (Fig. 216.1B).

Hypopharyngeal diverticuli are more likely to be lateral than midline posterior on a congenital basis but in childhood should be considered a developmental disorder regardless of condition.

Applied Anatomy

A thorough knowledge of hypopharyngeal anatomy and anatomic variations is required for the evaluation of developmental conditions of the hypopharynx. This anatomy is presented in detail with the introductory material on the hypopharynx and larynx (Chapters 201 and 215), oropharynx (Chapter 190), and related spaces of the neck (Chapters 142 and 149).

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The hypopharynx is studied in essentially the same manner for developmental abnormalities and benign masses of known or uncertain etiology as it is for the evaluation of known or suspected hypopharyngeal cancer. The principles of using these studies are reviewed in Chapter 190. Specific problem-driven protocols for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hypopharynx are presented in Appendixes A and B, respectively.

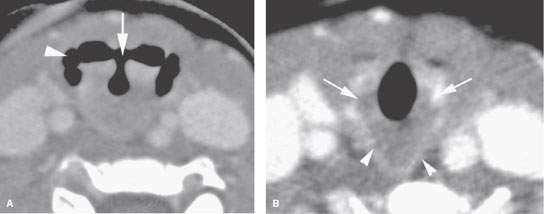

FIGURE 216.1. A 3-year-old patient presenting with sleep apnea and possibly aspiration. This contrast-enhanced computed tomography study shows an atypical arrangement of the supraglottic larynx and pharynx believed to be due to a cleft larynx or at least incomplete partition of the larynx and pharynx during development. A: The deformed laryngeal vestibule (arrow) bears an abnormal relationship to the pyriform sinuses (arrowhead). B: The abnormally shaped postcricoid portion of the hypopharynx (arrowheads) connects to the posterior aspect of the cricoid cartilage. More images of this patient are available in Figure 202.1.

There is little or no use for ultrasound in studying these conditions except for the in utero evaluation of fetal swallowing.

There is a limited role for catheter angiography in lesions where the physical examination and imaging with CT angiography and/or MRI suggests that they are vascular in origin or very hypervascular.

Radionuclide studies are generally not useful in these conditions except to confirm the presence of ectopic thyroid tissue as well as to confirm whether that ectopic tissue is the only functioning thyroid tissue present.

Pros and Cons

In general, these occur in younger age groups, so it is best to avoid radiation if possible. On the other hand, definitive MRI in children may require general anesthesia. These relative risks must be balanced. Either MRI or CT is usually definitive in the anatomic evaluation of these anomalies of development. One or the other may be more specific in some circumstances. MRI is more likely to be motion degraded, which may be particularly relevant when imaging small children.

Potentially developmental lesions that present as infections are better evaluated by CT. Such imaging is also more likely to show calcifications, if this is important for the differential diagnosis. MRI provides a better map of venolymphatic malformations and can help to characterize cystic masses with diffusion-weighted imaging.

There really is no generally correct or incorrect choice in this matter. The decision of which imaging study to use should be individualized based on age, likelihood of the correct diagnosis already being known from clinical information, and availability of imaging equipment and other factors just discussed.

Controversies

It might be argued that ultrasound should be used in the evaluation of these problems. It is frequently not definitive and is cost additive, so its use in general seems unjustified. If it can truly obviate other more risky studies and provide all the information necessary for medical decision making, then it would be of obvious benefit in such an unusual circumstance.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Dermoids, Epidermoids, Teratomas, Duplication Cysts, and Branchial Apparatus Abnormalities

Etiology

Branchial apparatus cysts are spontaneous developmental abnormalities that only uncommonly, except for third branchial arch anomalies, affect of the hypopharynx (Fig. 216.2). In the third/fourth apparatus anomalies, there is often a sinus tract present internally that connects to the hypopharynx.

Hypopharyngeal dermoids and epidermoids, if they ever affect the hypopharynx, may be from an extension of a rare one originating in the larynx. Hamartomas and teratomas may truly arise from the hypopharynx, but they are also extraordinarily rare.

Duplication (foregut) cysts of the hypopharynx are very rare; it is very difficult to anticipate this diagnosis precisely prior to removal (Fig. 216.3).

Clinical Presentation

These lesions will usually present as a palpable mass or because they interfere with swallowing. In an infant, the lesions may be detected by prenatal ultrasound but mainly will manifest at birth or shortly after birth as feeding problems, perhaps with aspiration.

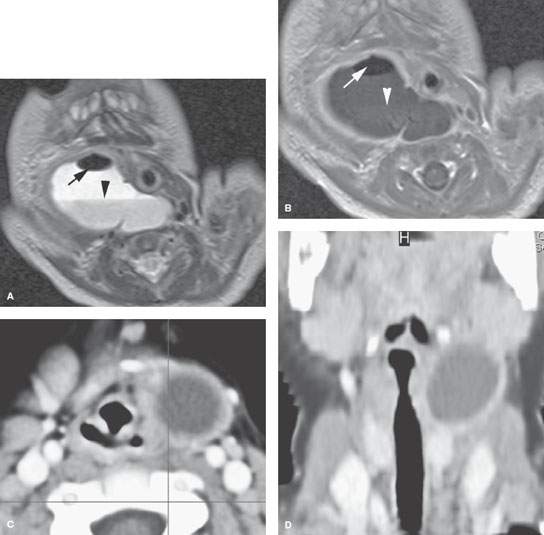

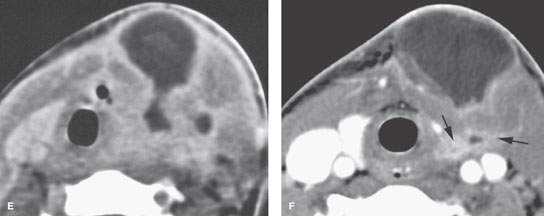

FIGURE 216.2. Four patients with cystic lesions possibly related to the hypopharynx at presentation. All patients presented with a neck mass; some have evidence of inflammation. Some patients also had a history of abnormal feeding or swallowing. A, B: Patient 1. A 3-year-old boy presenting with peritonsillar swelling. The T2-weighted axial (A) and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted coronal (B) images show a cystic mass in the parapharyngeal region that is intimately associated with the pharyngeal wall. This was a surgically confirmed branchial apparatus cyst. C, D: Patient 2. This cyst seen on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was intimately related to the wall of the pharynx and larynx and not in the usual position of the branchial apparatus cyst, but that was the final pathologic diagnosis. This could have been an epidermoid or duplication cyst. E, F: Patients 3 and 4 with third branchial apparatus cysts presenting as neck masses in the thyroid region with infection. The contrast-enhanced CT in (E) does not show a clear connection to the pharynx, but the tract does extend toward the lower hypopharynx. In (F), there appears to be a tract connecting to the postcricoid portion of the hypopharynx.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree