Study

Number of patients

Preoperative diagnosis

Imaging system

Dose of ICG

Injection site

Time between injection and imaging

Intraoperative IR (tumors)

Additional metastases identified

False-positive lesions

Smallest tumor size

Harada, 2010 [29]

3

ICC (n = 2); CLM (n = 1)

PDE

0.5 mg/kg

i.v.

4 days (1, 2) and 2 days (3)

3/3

–

0

20 mm

Ishizawa, 2009 [26]

49a

HCC (n = 37); CLM (n = 12)

PDE

0.5 mg/kg

i.v.

1–7 days for HCC and 1–14 days for CLM

21/41 HCCs and 16/16 CLMb

+

5

2 mm

Kasuya, 2011 [31]

1

CLM

PDE

500 μl mixed with ethanol

Locally

NA

NA

–

0

3 mm

Uchiyama, 2010 [33]

32

CLM

PDE

0.5 mg/kg

i.v.

<2 weeks

NA

+

2

4 mm

Yokoyama, 2012 [34]

49

PCM

PDE

25 mg

i.v.

1 day

NA

+

5

1.5 mm

Ishizuka, 2012 [30]

7

CLM

PDE

0.1 ml/kg

NA

NA

26/26

+

1

NA

Peloso, 2012 [32]

25

CLM

PDE

0.5 mg/kg

i.v.

24 h

NA/77

+

1

3 mm

403

CLMUMM

Mini-FLAREKarl Storz Fluorescence laparoscope

10 and 20 mg10 mg

i.v.i.v.

24 and 48 h24h

71/97NA

++

0+

1 mm\1 mm

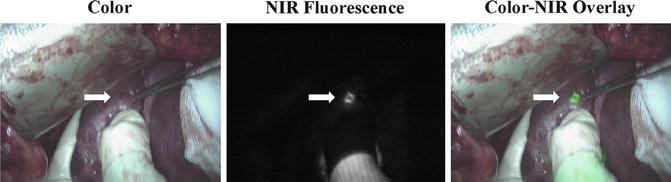

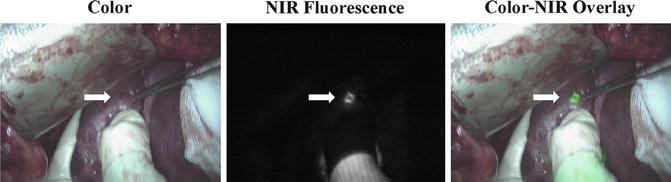

Fig. 16.1

In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging of a hepatic metastasis using the Mini-FLARE system (Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston, USA). A rim of fluorescence around the lesion is shown

Fig. 16.2

Ex vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging of resected and sliced lesion at pathology department using the FLARE imaging system (Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston, USA)

Fig. 16.3

Benign lesions (arrow) can be differentiated from malignant lesions by a lack of a near-infrared fluorescent rim around the lesion

One of the great challenges in NIR fluorescence imaging is still its limited capability to penetrate human tissue. None of the above-described studies reported the ability to detect metastases more than 8 mm below the liver capsule. For colorectal liver metastases, however, this technique is very useful, as colorectal liver metastases are mostly located on the surface of liver parenchyma. Deeper localized metastases also show a fluorescent rim after resection and sectioning (Fig. 16.2) [38], but detection of these tumors still needs conventional technologies. Although this is a great limitation, NIR fluorescence imaging also has major advantages. Conventional imaging technologies easily miss superficial liver metastases smaller than 10 mm [7, 9]. In NIR fluorescence imaging, the bright signal enables surgeons to detect lesions as small as 1 mm in real-time (Fig. 16.4) [7, 27]. Indeed, additional, otherwise undetectable metastases were identified in 7 studies [26–28, 30, 32–34]. Van der Vorst et al. report identification of otherwise undetectable liver metastases in 5 of 40 patients (12.5 %, 95 % CI = 5.0–26.6) [27]. Combining contrast-enhanced IOUS and NIR fluorescence imaging together with CT and MRI, Uchhiyama et al. improved diagnostic sensitivity in 32 consecutive patients from 88.5 % to 98.1 % (P=0.050) [33]. Yokoyama et al. showed the potential of using NIR fluorescence imaging by screening the hepatic surface during pancreatic surgery with curative intent [34]. In 49 patients without preoperative detected hepatic metastases, 13 abnormal fluorescent lesions were detected without any apparent tumor, and 8 of them contained micrometastases. Within 6 months after surgery, 10 patients with abnormal fluorescence developed hepatic metastases, versus 1 of 36 patients in the fluorescence negative group, resulting in a positive predictive value of 77 % and a negative predictive value of 97 %. This outcome could possibly help surgeons select patients for either curative or palliative treatment.

Fig. 16.4

Small, superficial, otherwise occult metastases are identified by near-infrared fluorescence imaging (arrow)

Other Applications of NIR Fluorescence Imaging During Hepatectomy

Besides tumor demarcation, excretion of ICG into the bile can be used for real-time cholangiography of the biliary anatomy. Iatrogenic damage of bile ducts is a major issue in liver surgery. Bile leakage after hepatic resection is associated with high risk for liver failure and postoperative mortality [39]. During cholangiography, the feasibility is shown by Ishizwa et al. [40]. Potentially, bile leakage could also be detected during resection of hepatic metastasis, though no study reports the feasibility. Another novel and intraoperative technique is the use of ICG for image-guided liver segment identification for anatomical hepatic resection. Aoki et al. performed a study in 35 patients who underwent hepatectomy for hepatic malignancy [41]. After administration of 5 mg ICG into the portal vein, stained subsegments and segments of the liver were identified in 33 of 35 patients. Both cholangiography and identification of liver segments are very usable during hepatic metastectomy and are described in Chap. 27.

Conclusion

Surgical resection is currently the only potentially curative therapy and standard-of-care for metastases in the liver in selected patients. The high recurrence rate demands a technology which is able to detect lesions that are otherwise undetected by current visualization methods. Current available literature suggests an important complementary role for intraoperative NIR fluorescence imaging in the detection of metastases and primary tumors in the liver. It enables the identification of otherwise undetectable metastases as small as 1 mm and localized on or up to 8 mm below the liver surface. Although several studies show promising results, larger clinical trials are required to truly validate the benefit for patient requiring partial liver resection. In addition, optimization of NIR fluorescent-contrast agents and imaging systems is necessary before NIR fluorescence imaging becomes standard-of-care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree