CHAPTER 9 Imaging Evaluation of Trauma

ROLE OF IMAGING IN TRAUMA

Ultrasound and Computed Tomography

Ultrasound, in contrast, can be used in the trauma room while members of the trauma team continue to assess and support the patient. Focused abdominal sonogram for trauma (FAST) has largely replaced diagnostic peritoneal lavage by providing a rapid noninvasive method for identifying hemoperitoneum. Box 9-1 shows the search pattern for FAST examination. Up to 40% of patients with injuries to the abdominal viscera are taken to the operating room immediately after sonographic determination of hemoperitoneum, and injuries are diagnosed during laparotomy rather than with CT.

A key limitation of the FAST examination is that nearly one in three injuries to the liver or spleen do not result in hemoperitoneum and are more likely to be identified on CT. Understanding the relative strengths and weakness of imaging modalities is an important step in creating effective trauma protocols. Table 9-1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of ultrasound and CT.

Table 9-1 Comparison of Ultrasound and Computed Tomography in Trauma Imaging

| Imaging Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | ||

| Computed tomography | ||

Blunt versus Penetrating Trauma

Imaging is routinely performed for blunt force trauma. Injury in blunt force trauma is the result of direct crush injury, sheer forces, or burst injury from an abrupt increase in intraluminal pressure. The most common source of blunt force trauma that requires imaging is motor vehicle collision. Victims of severe blunt force trauma with hemodynamic compromise may still require immediate surgical exploration, but occasionally even unstable patients require imaging if the site of injury is not apparent by physical examination. Imaging surveys often include CT examinations of the head, cervical spine, chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

KEY COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHIC FINDINGS IN THE TRAUMA PATIENT

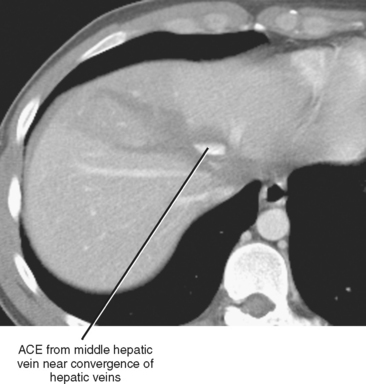

Contrast Extravasation

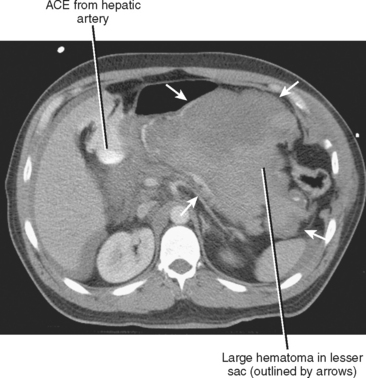

Active contrast extravasation (ACE) describes the presence of vascular contrast media outside the vascular space and is a direct sign of hemorrhage. Attenuation of extravasated contrast medium is as high as in major arterial structures nearby and is often located within or adjacent to a parenchymal laceration (Fig. 9-1). When ACE is present, transcatheter or surgical intervention is often required to stop the hemorrhage. Before the significance of ACE was known, some patients were managed with observation that included prolonged replacement of blood products and fluids. In this scenario, the patient can become coagulopathic by the time the intervention is performed, increasing risk of the procedure and potentially decreasing its efficacy. ACE is now considered to be a risk factor independent of other AAST criteria.

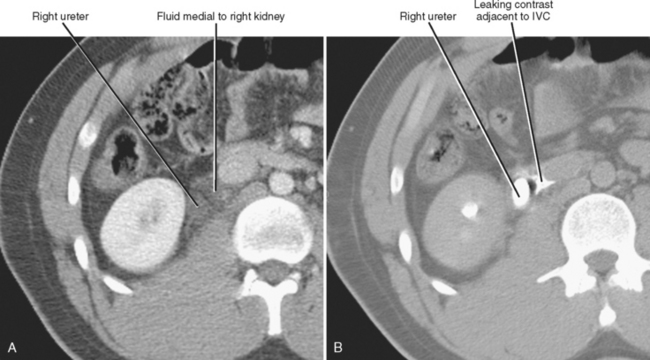

Leakage of excreted contrast material from the urinary tract is a highly specific sign of urinary tract injury. It is seen most often with injuries to the intrarenal collecting system and bladder, and only rarely with ureteral injuries. Because urine will be opacified only in the excretory phase, delayed (>2-3 minutes) CT images are helpful in confirming the diagnosis (Fig. 9-2).

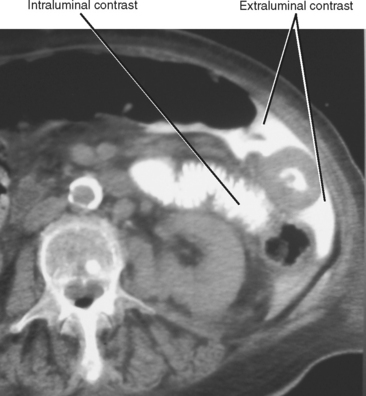

Some centers administer enteric contrast as part of the CT trauma evaluation in an attempt to increase sensitivity for gastrointestinal injury (Fig. 9-3). Because this technique can delay imaging (up to an hour for complete small-bowel opacification) and carries some increased risk for aspiration during surgery, many institutions no longer routinely use enteric contrast media in trauma patients.

Extraluminal Fluid and Air

Extraluminal fluid and air are important indirect signs of injury. It is critical to characterize the precise location of fluid and air in the abdomen because pathways of intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal spread are usually predictable and help direct the search for the site of injury (see Chapter 6).

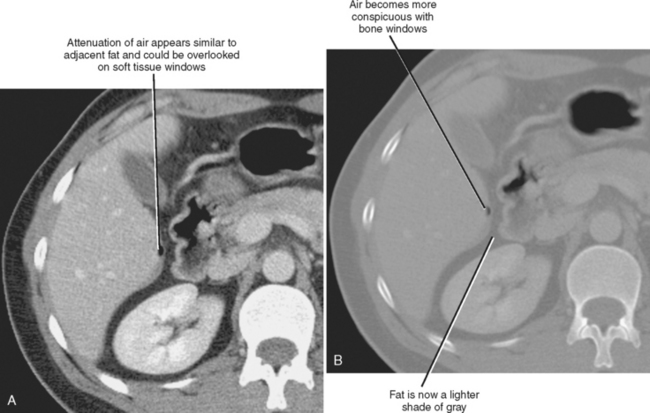

Large amounts of hemoperitoneum are often associated with injuries to the spleen or liver. Fluid in the lesser sac is usually associated with injury to the structures that form its borders (i.e., spleen, stomach, or pancreas) (Fig. 9-4). When extraperitoneal fluid or hemorrhage is present, look for injuries to the urinary tract, pancreas, and vessels such as the aorta and its major branches. Fluid within the mesentery and between bowel loops is better seen with CT than with ultrasound. When mesenteric injury is present, also look for evidence of bowel injury such as wall thickening, absent mural enhancement, or extraluminal gas. Remember to adjust window/level settings to make fat appear gray to facilitate detection of pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 9-5).

Signs of Hemodynamic Compromise

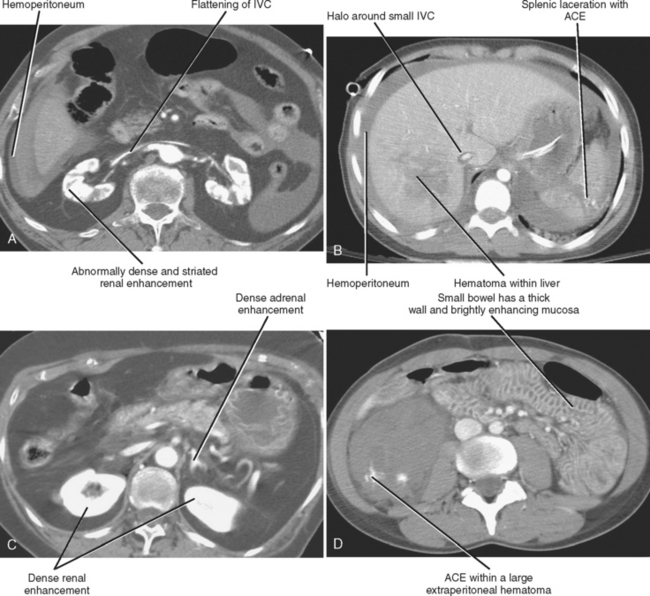

Aside from ACE, other CT findings indicate life-threatening hemorrhage. The most common are flattening of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and increased enhancement of the bowel, kidneys, and adrenal glands. Box 9-2 lists key findings of hemodynamic compromise. Figure 9-6 shows some of these findings.

HEPATIC TRAUMA

The liver is the largest solid organ in the abdominal cavity, and its relatively brittle parenchyma makes it susceptible to laceration and fracture from the compressive and shear forces of blunt abdominal trauma. The size of the liver also makes it the most commonly injured solid organ from penetrating injury. Although the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe and the interlobar region are most commonly injured, injuries can occur anywhere in the liver. Therapeutic options most commonly used to treat liver injury include transcatheter embolization, hepatotomy with vessel ligation, segmentectomy, and lobectomy. Despite these options, the mortality rate from liver injuries remains near 10%.

Types of Injury to the Liver

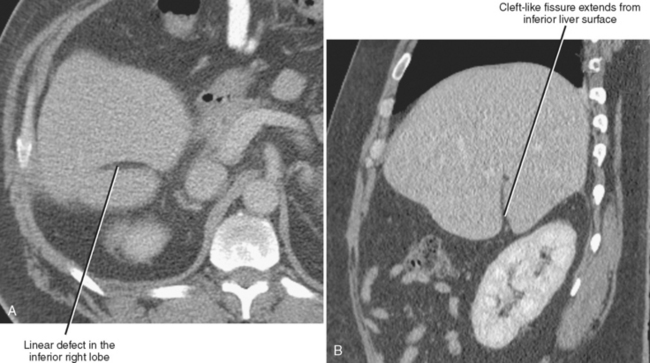

Injuries to the liver are classified into several types, listed in Box 9-3. The most common injuries are lacerations, which are parenchyma tears that extend to the liver surface. On contrast-enhanced CT, most lacerations appear as linear or curvilinear hypoattenuating defects. Characterization of a laceration should include its location and any important structures (particularly vascular structures) involved. A superficial laceration is sometimes called a capsular tear (Fig. 9-7). A laceration that continues from one liver surface to another (full thickness) is called a fracture.

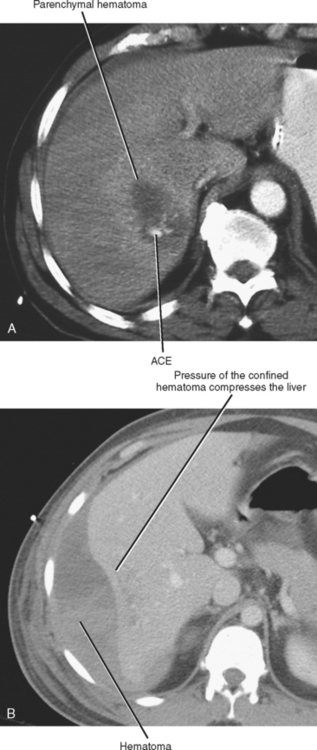

Hematomas are nonlinear (often lentiform or round) collections of blood within the liver parenchyma (Fig. 9-8). Subcapsular hematomas occur between the liver capsule and the hepatic parenchyma, and are often curvilinear or lentiform.

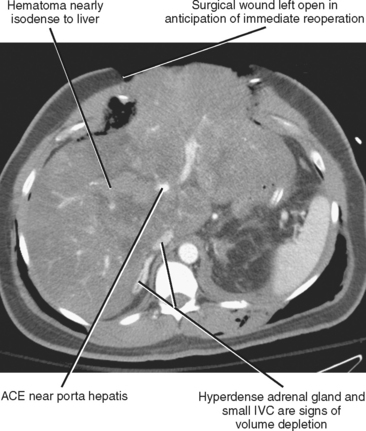

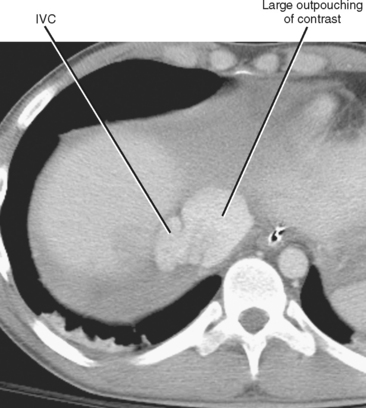

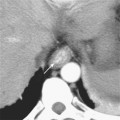

Portosystemic shunting, arteriovenous fistula, ACE, and infarction near areas of laceration are all signs of vascular injury. ACE can be seen within any type of hepatic hematoma, and should be noted and reported immediately because prompt transcatheter or surgical intervention can be lifesaving. Infarction occurs with transection of arterial and portal venous structures but should not occur with hepatic venous injury alone. Vascular avulsions or sheer injuries can occur within the porta hepatis (hepatic artery, portal vein, or both) (Fig. 9-9), or at either the superior or inferior margin of the hepatic attachment of the inferior vena cava (Fig. 9-10). Subtle laceration to the central hepatic veins can result in dramatic blood loss if exacerbated during manipulation by an unsuspecting surgeon (Fig. 9-11).

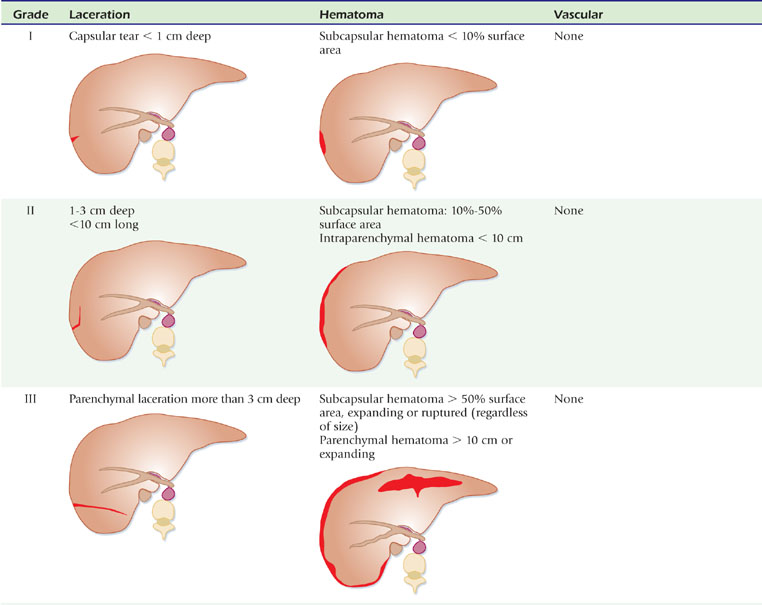

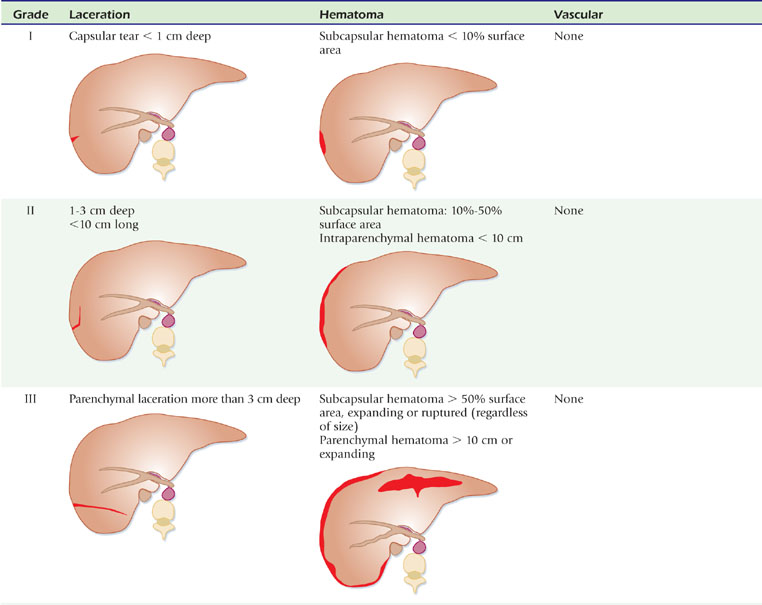

Grading Hepatic Trauma

Trauma surgeons use the classification system adopted by the AAST to stratify liver injuries. Table 9-2 summarizes the AAST classification. In most centers, the radiologist is not expected to provide the precise grading for the injury. However, knowledge of the classification system paired with precise observation of the relevant findings facilitates effective patient management. In most cases, the key imaging findings used for the AAST classification can be distilled to the short list included in Table 9-3.

Table 9-3 Key Imaging Findings in Hepatic Trauma

| Finding | Significance |

|---|---|

| Presence of active contrast extravasation | Likely to require embolization or surgery |

| Laceration to a central hepatic vein | Risk for severe hemorrhage when liver is moved during surgery |

| Central collection of low-attenuation fluid (rare) | Possible bile leak; consider endoscopic retrograde cholan-giopancreatogram or scintigraphy when stable |

| Regions of hepatic infarction (rare) | Vascular injury is present, increased risk for further hemorrhage |

Pitfalls in Imaging Hepatic Trauma

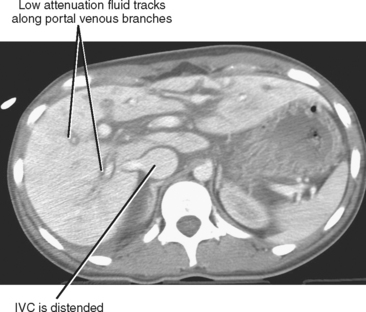

Hepatic fissures can also mimic laceration. Similarly, a laceration in the expected location of a normal fissure can be overlooked. Multiplanar reformations are useful when differentiating between fissures and lacerations (Fig. 9-12). Aggressive volume resuscitation can affect the appearance of the liver on contrast-enhanced CT images, with periportal edema resulting in a halo of low attenuation around portal branches (Fig. 9-13).

SPLENIC TRAUMA

With increasing understanding of postsplenectomy sepsis, nonoperative management of splenic injury has become increasingly emphasized in recent years. Because the risk for death from sepsis in patients who have undergone splenectomy is approximately 10 times that in the general population, efforts are made to preserve functioning splenic tissue whenever possible. Currently, at least 70% of patients with splenic injury who are hemodynamically stable are treated without surgery. Because delayed hemorrhage can be life threatening, patients with splenic injuries are often observed in an inpatient setting for at least 72 hours.

Types of Injury to the Spleen

As with the liver, most splenic injuries can be described as lacerations, hematomas, or vascular injuries. Small, superficial lacerations are commonly called capsular tears (Fig. 9-14). Hematomas contained by the splenic capsule are called subcapsular hematomas (Fig. 9-15). Although sometimes difficult to differentiate from areas of parenchymal hematoma, regions of devitalized spleen signify vascular injury (Fig. 9-16). ACE indicates severe vascular injury with active hemorrhage and usually requires immediate surgical or transcatheter intervention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree