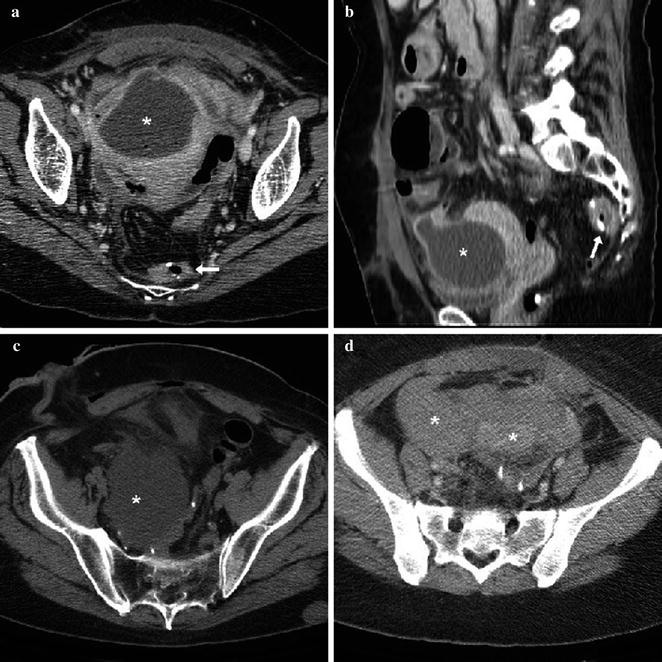

Fig. 15.1

Normal MDCT imaging appearance of an endoscopically unremarkable ileal pouch as seen on sagittal (a), coronal (b) and axial (c) images. Well distended by fluid-faecal content (*), the pouch reservoir occupies the original anatomic site of the rectum, and is identified by the presence of metallic staples facing each other (arrows). More caudally (d), the pouch-anal anastomosis is also identifiable (arrowhead) [Partly reprinted with permission from Ref. [11]]

In selected patients with chronic obstructive symptoms, an MDCT-enterography technique including small bowel distension via peroral ingestion of hyperdense or neutral enteral contrast material (such as polyethylene-glycol solution) may be beneficial to investigate low-grade or intermittent intestinal obstructive states [12–14].

More recently, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly used for the assessment of pouch-related inflammatory conditions. MRI provides an accurate multiplanar assessment of normal IPAA post-operative anatomy, and identification of possible complications. As from previous experiences with perianal inflammatory disease, intrinsic MRI advantages include its multiplanar capability, panoramic and detailed view, superb contrast resolution and possibility to suppress fat background, excellent visualization of abscesses and fistulas even with closed orifices, and detection of enhancement corresponding to inflammatory activity [10, 11, 15–17].

MRI is feasible even in patients with anal stenosis or pain, and its lack of irradiation and limited biologic invasiveness of gadolinium contrast are particularly beneficial in young patients who may need repeated imaging. MRI is performed with a phased-array coil positioned on the pelvis without any special patient preparation. Our protocol includes precontrast acquisition of multiplanar T2-weighted sequences, axial T1-weighted and fat-saturated (STIR) images. After intravenous paramagnetic contrast administration, enhanced multiplanar T1-weighted sequences are acquired, with fat suppression in at least one plane. Additionally, thin-section images may be planned on the perianal and perineal region if clinical or imaging findings suggest its possible involvement [11].

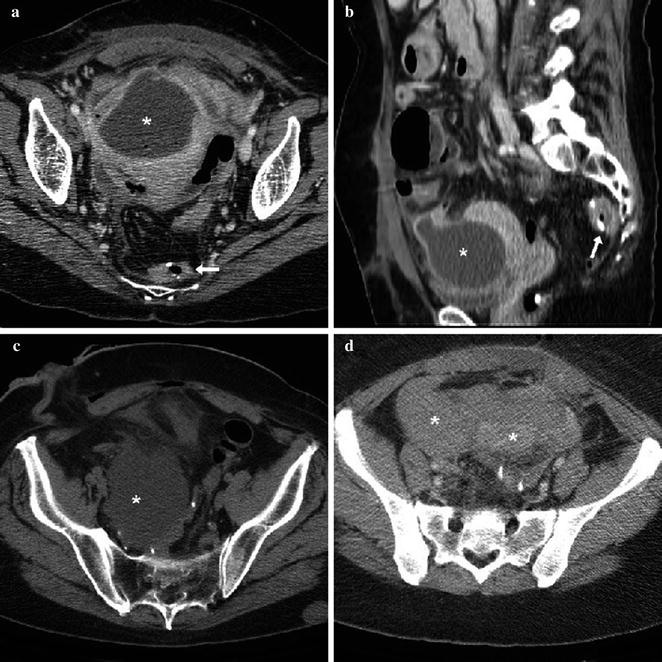

Similarly to MDCT, the ileal pouch is identified at MRI from the small ferromagnetic artefacts with signal voids on all sequences, due to the metallic staples (Fig. 15.2) [11, 15, 16].

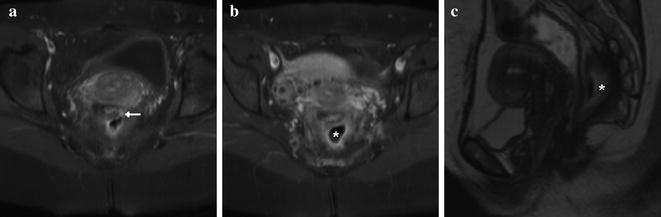

Fig. 15.2

Usual MRI appearance of a normal, moderately distended ileal pouch on axial T1- (a), coronal T2- (b) and post-contrast sagittal T1-weighted (c) images, with small ferromagnetic artefacts opposed to each other and due to presence of metallic staples (arrows) [Partly reprinted with permission from Ref. [11]]

The best accuracy in diagnosing complex IPAA-related disorders is achieved by a combination of pouch endoscopy with at least one imaging modality such as water-soluble contrast enema, MDCT and MRI [18]. According to our personal experience, pelvic MRI is highly valuable to complement pouch endoscopy in patients with proven or suspected pouchitis, abscesses or fistulas, to allow the differentiation of simple pouchitis from pelvic sepsis, which has been found even in patients with normal endoscopic findings and usually requires an aggressive therapy. Alternatively, when obstruction is suspected, contrast enema or MDCT may be performed before or after endoscopy to provide a more panoramic view of the entire abdomen and pelvis [11, 18].

15.2 Surgical and Mechanical Post-operative Complications

In our experience, cross-sectional imaging is often requested during the post-operative hospitalization following RPC−IPAA procedures when early surgical complications are suspected. In the majority of patients, indication for urgent studies include persistent abdominal pain, tenderness or peritonitis, fever, abnormal drainage from tubes, failure to achieve canalization and laboratory signs indicating blood loss or elevated acute phase reactants.

Although plain abdominal radiographs sometimes provide useful information, in most instances prompt investigation with contrast-enhanced MDCT is beneficial for comprehensive assessment of the abdomen and pelvis, and is felt highly helpful by our surgeons to guide the patient’s management.

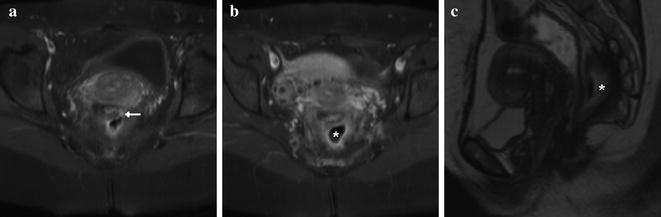

When performing and interpreting imaging studies in patients with recent or previous IPAA surgery, precise knowledge of surgical technique details and timing is needed to elucidate early post-operative conditions that may sometimes require reintervention. On the basis of our experience, we recommend a consistent approach to study interpretation, whether it refers to problems occurring after the first surgical procedure (subtotal colectomy, ileal pouch creation and covering loop ileostomy), following ileostomy takedown, or after a one-stage procedure without temporary ileostomy. The different elements characteristic of RPC-IPAA surgery should be thoroughly reviewed, including the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis, the morphology and distension of the pouch reservoir including its afferent and efferent limbs, the peripouch fat planes and the ileostomy (Fig. 15.3).

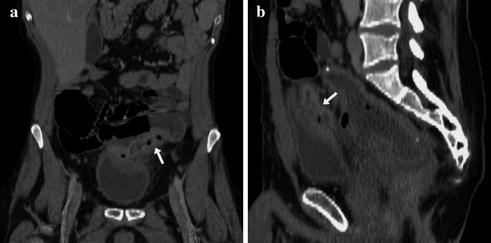

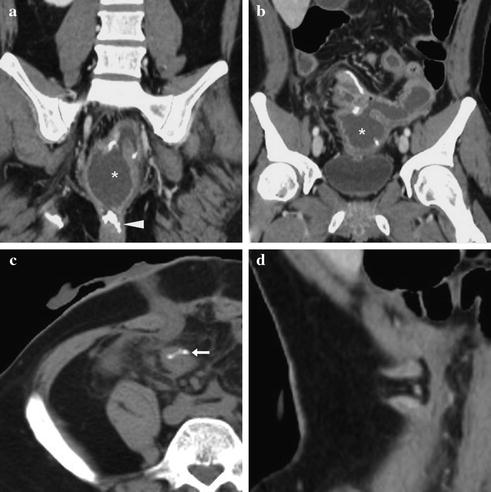

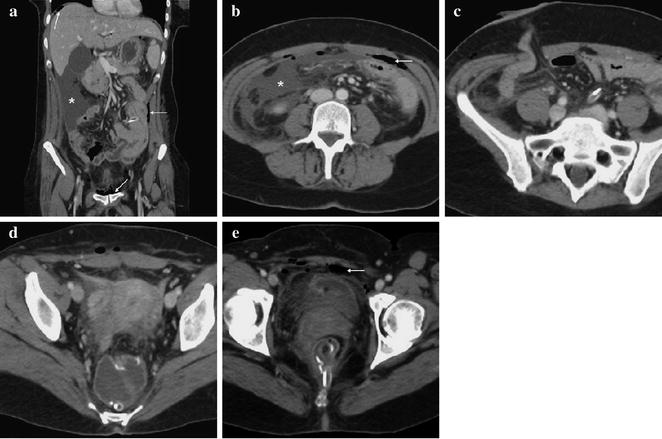

Fig. 15.3

Approach to interpretation of an early post-operative MDCT study. Multiplanar examination review should focus on the pouch-anal anastomosis (arrowhead in a), morphology and size of the pouch reservoir (*) including its afferent and efferent limbs (b) and sutures (c), the peripouch fat planes and the presence and features of the ileostomy (c, d)

15.2.1 Anastomotic Dehiscence and Leaks

Defined by Shen, Fazio et al. as “anastomotic separation leading to exodus of pouch luminal content”, anastomotic leak most usually occurs at the pouch-anal anastomosis, whereas less common sites include the tip of the J pouch, and the pouch body along the staple line [7].

Although small leaks may not cause pelvic sepsis, anastomotic dehiscence is a critical diagnosis that usually dictates surgical reintervention and repair, and requires prolonged faecal diversion, suture lines should be carefully scrutinized on MDCT. In the past, contrast extravasation during pouchography in the soft tissues surrounding the pouch-anal anastomosis was the diagnostic hallmark of leakage [8–10].

Currently, MDCT represents the first-line investigation in most instances. Although the anastomotic leak may not be directly identified, MDCT is extremely sensitive for the detection of extraluminal air (Fig. 15.4a, b), fluid collections or hyperattenuating contrast material (Fig. 15.4c, d). These findings should be sought for, and reported as abnormal, since they strongly suggest anastomotic dehiscence [8–10, 15, 16].

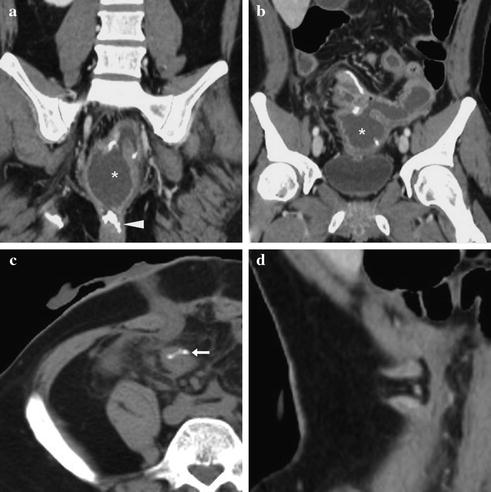

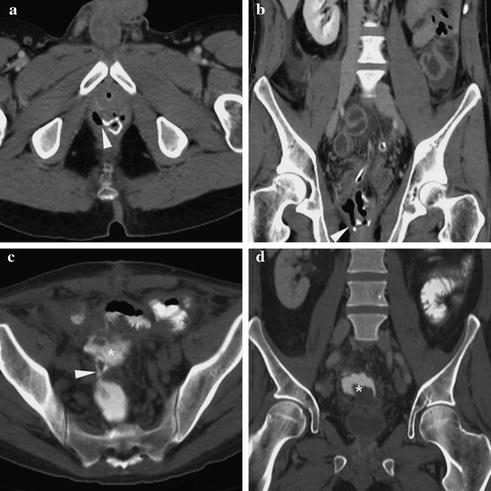

Fig. 15.4

Early dehiscence of the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis identified on axial (a) and coronal (b) MDCT images by extraluminal air leak on the right side (arrowheads) that required surgical reoperation. In a different patient, MDCT acquisition after peroral administration of hyperattenuating iodine-based contrast medium (c, d) reveals extraluminal collection (*) opacified through a contrast leak (arrowhead in c), a finding that prompted surgical reintervention with pouch excision and permanent ileostomy

Finally, persistent intraperitoneal air and MDCT findings suggesting peritonitis (Fig. 15.5) should alert the possible presence of extraluminal leak, even with normal appearances at the ileostomy and surgical anastomoses.

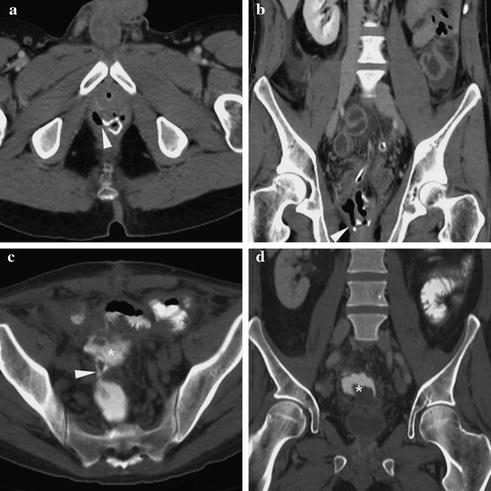

Fig. 15.5

Peritonitis following proctocolectomy with J pouch creation and ileostomy. Multiplanar MDCT images show peritoneal fluid (*) and serosal thickening, persistent air in the peritoneal cavity and subperitoneal Retzius’ space (thin arrows), and normal appearances of the ileostomy (c), ileal pouch (d) and pouch-anal anastomosis (e). Reintervention confirmed biliary peritonitis due to focal ileal rupture above the ileostomy that was repaired

15.2.2 Post-operative Pelvic Sepsis, Pouch Abscesses, Sinuses and Fistulas

The definition of IPAA-related pelvic sepsis includes any infectious process developing in the peripouch area or distally to the pelvic inlet. Clinical manifestations may include local pain, purulent discharge from fistulous orifices, fever and abnormal acute phase reactants, sometimes vaginal drainage, pneumaturia, fecaluria or frequent urinary tract infections [7]. Globally, pelvic sepsis is diagnosed with a prevalence of 6–37 %, and represents the main cause of pouch failure in UC patients, leading to pouch excision of 30 % of cases, and is associated with a 3 % mortality rate [5–7].

Early post-operative sepsis occurs in 5–20 % of patients undergoing RPC with IPAA. Even in the absence of demonstrable anastomotic leaks, on post-operative MDCT studies abnormal collections suggesting pelvic sepsis should be carefully sought for, particularly nearby the ileostomy site and surgical anastomoses. The MDCT hallmark of an abscess is represented by a fluid-like collection surrounded by a well-defined, variable-thickness enhancing rim (Fig. 15.6a, b). Alternative diagnoses such as fluid-attenuating serous (Fig. 15.6c) or hyperattenuating hemorrhagic collections (Fig. 15.6d) may be proposed on the basis of imaging findings [15, 16].

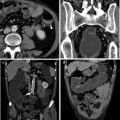

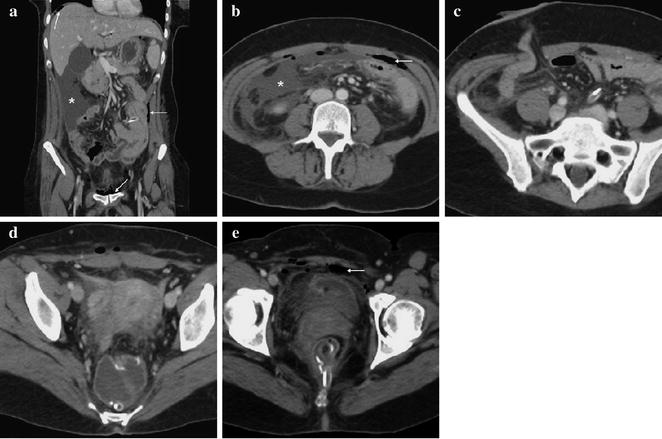

Fig. 15.6

Pelvic abscess collection (a, b) with enhancing rim and internal fluid-like content following proctocolectomy. Note normal appearance of the collapsed ileal pouch (arrows). In another patient with ileostomy (c), a fluid-attenuating collection without perceptible walls (*) corresponded to serous fluid at evacuation. In a third patient (d), extensive hyperattenuating haemorrhage (*) was detected in the Retzius’ subperitoneal space

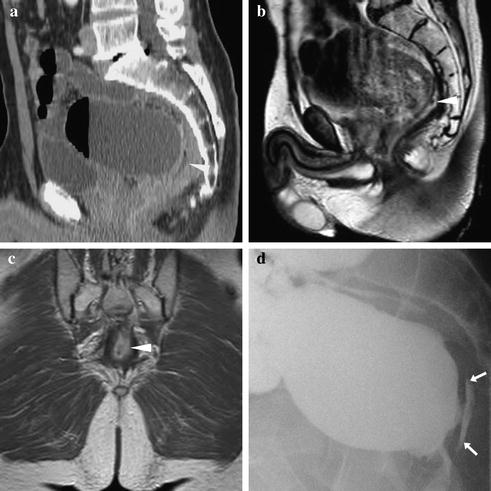

In the majority of cases, early post-operative sepsis results from leakage at the site of the pouch-anal anastomosis (Fig. 15.7). Whereas a sinus is a blind tract that originates from the pouch-anal anastomosis (Fig. 15.8) and may lead to the formation of an abscess, a pouch-related fistula involves an abnormal communication between any level of the ileal pouch epithelium and a different structure, such as the ischioanal space, perineal skin and subcutaneous planes, vagina or urinary bladder (Fig. 15.9). Both entities usually result from a later presentation of an initial anastomotic leak [7, 11].

Fig. 15.7

Pelvic sepsis in a patient with perineal pain and purulent discharge. MRI shows dehiscence at the pouch-anal anastomosis as an enhancing leak (arrow in a) giving rise to a large retropouch abscess (*) [Reprinted with permission from Ref. [11]]

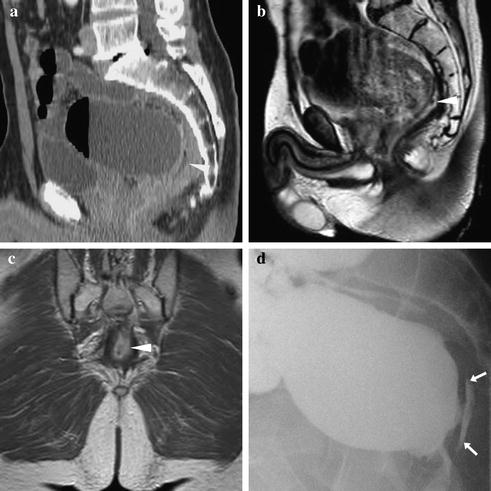

Fig. 15.8

Pouch sinus in a patient with chronic low-grade pelvic sepsis, endoscopic detection of fistulous orifices at the pouch-anal anastomosis. Contrast-enhanced MDCT (a) and MRI (b, c) detect an enhancing structure with central fluid-like structure (arrowheads) located behind the dilated ileal pouch reservoir. Fluoroscopic pouchography (d) detects contrast extravasation (arrows) opacifying the central portion, indicating the presence of a pouch sinus