A variety of congenital, traumatic, vascular, inflammatory, and neoplastic processes may affect the facial nerve. Prudent use of CT and MR imaging combined with a complete understanding of facial nerve anatomy helps in narrowing the differential diagnosis. The precise anatomic course of the facial nerve must be charted in patients who undergo middle ear surgery. Also of great importance is recognition of the fact that the facial nerve may be affected in cancers of the head and neck by perineural spread. This article reviews the anatomy of the facial nerve and relevant, current clinical evaluation and imaging strategies.

Imaging plays an important role in the evaluation of the complex anatomy of the facial nerve. The nerve is affected by a wide variety of primary pathologic processes and may also be secondarily involved in several congenital, inflammatory, and traumatic and neoplastic disorders of the temporal bone and parotid gland. Conceptually, the facial nerve is best divided along its course into several segments. Some disease processes may involve one segment, whereas others may involve multiple segments.

Anatomy

The facial nerve is a complex nerve with motor, sensory, and parasympathetic fibers. The motor division is dominant, accounting for approximately 70% of the total axons, with the remainder composed of the sensory division and the nervus intermedius (nerve of Wrisberg). A very important clinical observation in the evaluation of the facial nerve is in distinguishing central and peripheral facial weakness. To a careful clinician, the location of pathologic factors can be deduced based on specific signs and symptoms. A well-understood concept used in clinical evaluation of the facial nerve is that a central palsy spares the forehead and brow, whereas a peripheral palsy involves the entirety of the facial musculature along with loss of emotional or involuntary facial motion. This is the result of the typical bilateral supranuclear innervation of the upper facial musculature. The motor division supplies somatic motor fibers to the muscles of the face, scalp, and auricle, the buccinator and platysma, the stapedius, the stylohyoideus, and the posterior belly of the digastric; it also contains some sympathetic motor fibers, which constitute the vasodilator nerves of the submandibular and sublingual glands and are conveyed through the chorda tympani nerve. The facial nerve also demonstrates clinically relevant communications with other cranial and cervical spinal nerves ( Table 1 ).

| Site | Communication |

|---|---|

| Internal acoustic meatus | Vestibulocochlear nerve |

| Geniculate ganglion |

|

| Facial canal | Auricular branch of the vagus nerve. |

| Stylomastoid foramen | With the glossopharyngeal, vagus, great auricular (C2, C3), and the auriculotemporal (V3) nerves |

| Behind the ear | With the lesser occipital nerve |

| On the face | With the trigeminal nerve |

| In the neck | With the cutaneous cervical nerve |

Supranuclear Control: Upper Motor Neuron

The supranuclear contribution from the motor cortex originates from pyramidal neurons located in the lower third of the precentral gyrus of the frontal motor cortex. The cortical representation of the face, from the uppermost cortex to the lower, begins with the forehead, followed by the periorbital, midface, and perioral muscles, with the motor cortex for the tongue following them. The cortical projection fibers join the corticobulbar tract and pass within the posterior aspect of the genu of the internal capsule into the medial third of the cerebral peduncle within the midbrain. Coursing inferiorly through the pontine pyramidal tract, most fibers decussate in the caudal pons to reach the contralateral facial motor nucleus. Some fibers do not decussate, and synapse in the ipsilateral facial nucleus. The cortical projection fibers for the upper face demonstrate incomplete decussation, and project to the ipsilateral and the contralateral facial nuclei. However, the supranuclear fibers for the lower facial muscles completely decussate to the contralateral facial nucleus. Hence, unilateral supranuclear lesions often somewhat spare the functions of the upper face.

A neglected aspect is the emotional control of facial motion provided by extrapyramidal input, which travels within the reticular formation from the frontal areas, thalamus, and globus pallidus to the facial motor nucleus. When a supranuclear lesion spares this input, emotional facial expressions are generally preserved, despite the presence of facial palsy. Hence, lesions of the midbrain or thalamus can cause contralateral palsy of emotional facial expressions with intact voluntary motion. Also, lesions of the globus pallidus or its projections to the facial nucleus can cause facial bradykinesia.

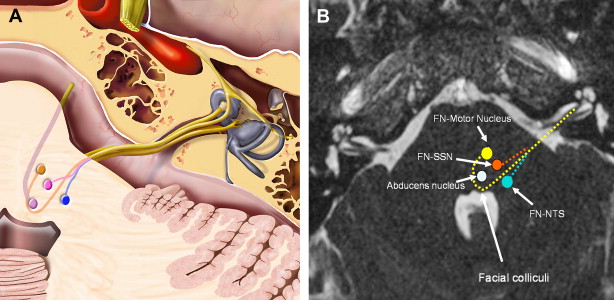

Motor Nucleus

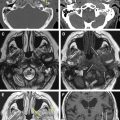

The motor nucleus of the facial nerve lies within the reticular formation of the lower third of the pons, situated above the nucleus ambiguus, behind the superior olivary nucleus, and medial to the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve. From this origin, the fibers first pass backward and medially toward the rhomboid fossa, then reach the posterior end of the nucleus of the abducens nerve, run upward beneath the facial colliculi and under the floor of the fourth ventricle. After looping around the abducens nucleus, the fibers travel laterally and caudally between the medial border of the trigeminal nucleus and the lateral edge of the facial motor nucleus. This anatomic relationship explains how certain disorders of facial nerve motor function can be associated with abducens palsy ( Fig. 1 ). The motor fibers finally exit the caudolateral border of the pons in the cerebellopontine angle medial to cranial nerve VIII (CN; vestibulocochlear nerve). The medial-to-lateral loop around the abducens nucleus is called the internal genu of the facial nerve.

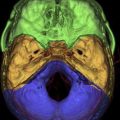

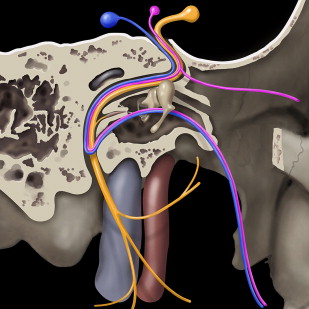

Nervus Intermedius and Sensory Nucleus

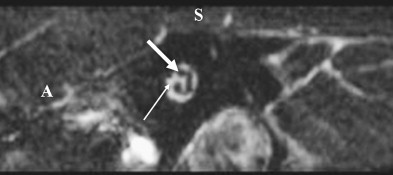

The nervus intermedius (also called the nerve of Wrisberg) contains specialized fibers that convey sensation from the posterior region of the external auditory canal and concha; taste from the anterior two thirds of the tongue; and secretomotor function for the lacrimal glands, submandibular and sublingual glands, and minor salivary glands in the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and palate. In the cerebellopontine angle (CPA), the nervus intermedius travels from the pons to the internal auditory meatus between the motor root and CN VIII. The chorda tympani and the greater superficial petrosal nerve (GSPN) are subdivisions of this nerve ( Fig. 2 ).The nervus intermedius also carries the somatic sensations from the posterior aspect of the external auditory canal, pinna, and mastoid region (within the posterior auricular nerve to the dorsal part of the primary sensory nucleus of trigeminal nerve within the pons).

Parasympathetic Nucleus

The parasympathetic component of the facial nerve originates from the superior salivatory nucleus in the dorsal pons. The facial nerve provides presynaptic parasympathetic fibers to the sphenopalatine and pterygopalatine ganglion for innervation of the lacrimal glands and to the submandibular ganglion for innervation of the sublingual and submandibular salivary glands. The pterygopalatine ganglion is associated with the maxillary nerve (CN V2), whose postsynaptic fibers it distributes, whereas the submandibular ganglion is associated with the mandibular nerve (CN V3). Nerve fibers for these nerves are carried distally from the pons to the geniculate ganglion within the nervus intermedius. The supply to the lacrimal gland is through the GSPN, which arises at the geniculate ganglion and travels anteromedially through the middle cranial fossa within the pterygoid canal. The GSPN then joins with the deep petrosal nerve (sympathetic) at the foramen lacerum to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal (vidian nerve), which travels through the pterygoid canal to terminate in the pterygopalatine ganglion in its fossa. Postganglionic parasympathetic fibers from there innervate the lacrimal gland by way of the zygomatic branch of CN V2, which passes these fibers on to the lacrimal nerve, which is a branch of CN V1.

The preganglionic fibers for the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands pass through the geniculate ganglion and then leave the mastoid segment of the facial nerve within the chorda tympani. The chorda tympani travels through the temporal bone, medial to the handle of malleus, and enters the infratemporal fossa by way of the petrotympanic fissure, where it joins the lingual nerve (CN V3). The parasympathetic fibers synapse with postganglionic cells within the submandibular ganglion, which then innervate the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands.

Nucleus Tractus Solitarius

This nucleus receives taste sensation from the anterior two thirds of the tongue, traveling within the chorda tympani (see Fig. 2 ). The cell bodies for taste fibers are located within the geniculate ganglion, with afferent fibers being carried centrally by the nervus intermedius to cells in the nucleus tractus solitarius in the medulla.

Peripheral course of facial nerve

The peripheral course is subdivided into the cisternal segment in the CPA, the intracanalicular segment in the internal auditory canal (IAC), the labyrinthine segment, the tympanic segment, the mastoid segment, and the extracranial segment.

Cisternal Segment in the Cerebellopontine Angle

The motor root and the nervus intermedius emerge from the brain stem ventrolaterally near the dorsal pons and travel anterolaterally into the IAC (see Fig. 1 ), with the nervus intermedius between the motor root of the facial nerve and the vestibulocochlear nerve (hence its name). The vestibulocochlear nerve travels laterally and slightly inferiorly to the facial nerve. The trigeminal nerve is located anteriorly. The anterior inferior cerebellar artery is associated with the nerves and usually is found ventrally, between the nerves and the pons. In the CPA, the facial nerve has no epineurium and is covered only by the pia mater.

Internal Auditory Meatus of the Temporal Bone

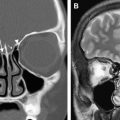

At the internal auditory meatus of the temporal bone, the nervus intermedius joins the motor root to form a common trunk that occupies the area known as the nervi facialis, which lies within the anterosuperior segment of the meatus ( Fig. 3 ). The motor fibers are more anterior, whereas the nervus intermedius fibers remain posterior. At the lateral end of the meatus, a horizontal partition of dura, and occasionally of bone, which is called the transverse or falciform crest, separates the facial nerve from the cochlear nerve inferiorly. Additionally, an incomplete vertical dural and osseous crest (Bill’s bar) separates the facial nerve from the superior vestibular nerve, which is located posteriorly. The blood supply to this region is from the labyrinthine artery, which is a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Facial/Fallopian Canal

The facial/fallopian canal consists essentially of three segments, the labyrinthine, tympanic, and mastoid, and it extends from Bill’s bar to the stylomastoid foramen.

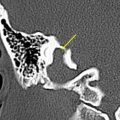

The labyrinthine segment ( Fig. 4 ) extends from the anterosuperior region of the fundus to the geniculate ganglion. It passes between the ampulla of the superior semicircular canal and the cochlea to travel forward and downward. At the geniculate ganglion, the nerve makes an abrupt sharp turn posteriorly, thus creating the external genu. This marks the beginning of the tympanic segment. Exiting anteriorly from the geniculate ganglion is the first branch of CN VII, the greater superficial petrosal nerve (GSPN). The tympanic segment continues along the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, medial to the incus. It courses superior and posterior to the cochleariform process, along the upper edge of the oval window, and inferior to the lateral semicircular canal (see Fig. 4 ). At the origin of the stapedius tendon from the pyramidal process, the nerve turns inferiorly to become the mastoid segment (see Fig. 4 ). The mastoid segment has two branches: the nerve to the stapedius and the chorda tympani. During its course through the mastoid along the posterior aspect of the external auditory canal, the nerve travels slightly posteriorly and usually passes lateral to the inferior aspect of the tympanic annulus. The major blood supply for the facial nerve within the facial canal is the superficial petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery (proximally) and the stylomastoid artery (distally).

Stylomastoid Foramen and Extracranial Segment

The facial nerve exits the temporal bone by way of the stylomastoid foramen, deep in the posterior belly of the digastric, and immediately enters the parotid gland. Shortly afterward, the nerve divides into its two terminal branches: the upper temporofacial nerve and a lower cervicofacial nerve at the posterior border of the ramus of the mandible. In the parotid gland, these nerves further divide to form the parotid plexus, which has five major branches: the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. Imaging procedures are not routinely able to visualize these branches of the facial nerve in their normal state.

Vascular Supply of the Facial Nerve

The cortical motor area of the face is supplied by the branches of the middle cerebral artery. The facial nucleus within the pons receives its blood supply primarily from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA). The AICA, which is a branch of the basilar artery, enters the IAC with the facial nerve. The AICA branches into the labyrinthine and cochlear arteries. The superficial petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery also supplies the intrapetrosal facial nerve. The posterior auricular artery supplies the facial nerve at and distal to the stylomastoid foramen. Venous drainage parallels the arterial blood supply. Also, mild enhancement of the labyrinthine segment, geniculate ganglion, and proximal tympanic segments can be normal on postcontrast MR, presumably secondary to the presence of a circumneural venous plexus in these segments.

Peripheral course of facial nerve

The peripheral course is subdivided into the cisternal segment in the CPA, the intracanalicular segment in the internal auditory canal (IAC), the labyrinthine segment, the tympanic segment, the mastoid segment, and the extracranial segment.

Cisternal Segment in the Cerebellopontine Angle

The motor root and the nervus intermedius emerge from the brain stem ventrolaterally near the dorsal pons and travel anterolaterally into the IAC (see Fig. 1 ), with the nervus intermedius between the motor root of the facial nerve and the vestibulocochlear nerve (hence its name). The vestibulocochlear nerve travels laterally and slightly inferiorly to the facial nerve. The trigeminal nerve is located anteriorly. The anterior inferior cerebellar artery is associated with the nerves and usually is found ventrally, between the nerves and the pons. In the CPA, the facial nerve has no epineurium and is covered only by the pia mater.

Internal Auditory Meatus of the Temporal Bone

At the internal auditory meatus of the temporal bone, the nervus intermedius joins the motor root to form a common trunk that occupies the area known as the nervi facialis, which lies within the anterosuperior segment of the meatus ( Fig. 3 ). The motor fibers are more anterior, whereas the nervus intermedius fibers remain posterior. At the lateral end of the meatus, a horizontal partition of dura, and occasionally of bone, which is called the transverse or falciform crest, separates the facial nerve from the cochlear nerve inferiorly. Additionally, an incomplete vertical dural and osseous crest (Bill’s bar) separates the facial nerve from the superior vestibular nerve, which is located posteriorly. The blood supply to this region is from the labyrinthine artery, which is a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Facial/Fallopian Canal

The facial/fallopian canal consists essentially of three segments, the labyrinthine, tympanic, and mastoid, and it extends from Bill’s bar to the stylomastoid foramen.

The labyrinthine segment ( Fig. 4 ) extends from the anterosuperior region of the fundus to the geniculate ganglion. It passes between the ampulla of the superior semicircular canal and the cochlea to travel forward and downward. At the geniculate ganglion, the nerve makes an abrupt sharp turn posteriorly, thus creating the external genu. This marks the beginning of the tympanic segment. Exiting anteriorly from the geniculate ganglion is the first branch of CN VII, the greater superficial petrosal nerve (GSPN). The tympanic segment continues along the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, medial to the incus. It courses superior and posterior to the cochleariform process, along the upper edge of the oval window, and inferior to the lateral semicircular canal (see Fig. 4 ). At the origin of the stapedius tendon from the pyramidal process, the nerve turns inferiorly to become the mastoid segment (see Fig. 4 ). The mastoid segment has two branches: the nerve to the stapedius and the chorda tympani. During its course through the mastoid along the posterior aspect of the external auditory canal, the nerve travels slightly posteriorly and usually passes lateral to the inferior aspect of the tympanic annulus. The major blood supply for the facial nerve within the facial canal is the superficial petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery (proximally) and the stylomastoid artery (distally).

Stylomastoid Foramen and Extracranial Segment

The facial nerve exits the temporal bone by way of the stylomastoid foramen, deep in the posterior belly of the digastric, and immediately enters the parotid gland. Shortly afterward, the nerve divides into its two terminal branches: the upper temporofacial nerve and a lower cervicofacial nerve at the posterior border of the ramus of the mandible. In the parotid gland, these nerves further divide to form the parotid plexus, which has five major branches: the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. Imaging procedures are not routinely able to visualize these branches of the facial nerve in their normal state.

Vascular Supply of the Facial Nerve

The cortical motor area of the face is supplied by the branches of the middle cerebral artery. The facial nucleus within the pons receives its blood supply primarily from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA). The AICA, which is a branch of the basilar artery, enters the IAC with the facial nerve. The AICA branches into the labyrinthine and cochlear arteries. The superficial petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery also supplies the intrapetrosal facial nerve. The posterior auricular artery supplies the facial nerve at and distal to the stylomastoid foramen. Venous drainage parallels the arterial blood supply. Also, mild enhancement of the labyrinthine segment, geniculate ganglion, and proximal tympanic segments can be normal on postcontrast MR, presumably secondary to the presence of a circumneural venous plexus in these segments.

Facial nerve paralysis—clinical evaluation and imaging strategies

Facial paralysis may be consequent to a wide variety of central and peripheral disorders ( Table 2 ). Evaluation of the patient who has facial palsy begins with a detailed history and thorough clinical examination. The severity of paralysis is commonly judged based on the House-Brackmann Facial Nerve Grading System, although many other grading systems exist ( Table 3 ). It is usually possible to distinguish between upper and lower motor neuron causes of facial paralysis based on the observation that an upper motor neuron process tends to spare the upper face because of the bilaterality of supranuclear control, whereas a lower motor neuron process affects the upper and lower facial musculature. It may also be possible to localize, in some instances, the precise level of lower motor neuron facial palsy based on affliction of the GSPN (lacrimation), nerve to stapedius (hyperacusis), and the chorda tympani (impaired taste and salivation). Lesions may therefore be classified as suprageniculate, suprastapedial, and suprachordal, respectively. In many instances, such localization is not possible because lesions may span several segments of the nerve.

| Type of Paralysis | Cause |

|---|---|

| Supranuclear | Cerebral infarction, hemorrhage, vascular lesions, demyelinating diseases, brain tumors, trauma, cardiofacial (opercular) syndrome |

| Brainstem |

|

| Cisternal and intracanilicular |

|

| Intratemporal |

|

| Extratemporal |

|

| Miscellaneous | Myasthenia gravis, diabetes, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, alcoholism, exposure to thalidomide or misoprostol |

| Congenital | Mobius, Di George, Poland, Goldenhar, CHARGE, and trisomy 13 and 18 syndromes |

| Idiopathic | Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, hereditary hypertrophic neuropathy, temporal arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa and other vasculitides, Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome (ascending paralysis) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree