Ileal pouches have drastically improved the quality of life in patients requiring total proctocolectomy. There are unique imaging characteristics of the pouch and its complications that radiologists should be familiar with. In this review, the authors discuss the anatomy of the pouch, commonly encountered complications, and the role of imaging in pouch assessment.

Key points

- •

Ileal pouches are a surgically created fecal reservoir with distinct anatomic and physiologic characteristics.

- •

Imaging plays a critical role in the assessment of function and complications of patients with ileal pouches and can help to guide management in this complex patient population.

- •

Several imaging modalities are used in pouch imaging, and the optimal choice of modality depends upon the specific clinical scenario.

Introduction

First described more than 45 years ago, restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) has revolutionized the management of patients with ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis syndromes. The ileoanal pouch improves the quality of life in proctocolectomy patients by avoiding permanent ileostomy while maintaining fecal continence. The pouch represents a unique segment of small bowel imaging, functioning as a surgically created fecal reservoir with distinct anatomic and physiologic characteristics relative to both the normal rectal reservoir and normal small bowel. Imaging plays a critical role in the assessment and management of ileal pouches. Although there is a growing centralization of pouch surgery toward a small number of highly specialized centers, all radiologists should be familiar with the ileal pouch.

Imaging technique

Several imaging modalities are routinely utilized in ileal pouch imaging. The choice of modality depends on the specific clinical question, surgeon preference, patient tolerance (eg, for catheter placement into the pouch, or the ability to lie still for MR imaging), and local radiologist expertise. Several excellent resources are available for imaging parameters to aid in setting up a pouch imaging service. , Table 1 provides an overview of pouch imaging modalities, including situations in which modalities may be preferred.

| Modality | Overview | Early Post-Operative Period | Late Post-Operative Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroscopy (Pouch Enema) | Flexible catheter inserted into the anus with the patient in lateral positioning, with gentle hand injection of water-soluble contrast. Excellent assessment of pouch anatomy and pathology such as leaks/fistulae | Primary imaging modality to assess for leak prior to loop ileostomy reversal | Variable usage patterns although still frequently used as first or second-line imaging in late postoperative assessment. Should be combined with a dynamic pouch defecography to assess pouch function in any patient with dyschezia. |

| MR Imaging | Superior soft tissue contrast. intravenous (IV) contrast preferred to assess for enhancing leaks/fistulae. Gel instilled directly into pouch or vagina may be used depending on indication | Less frequently used due to ready availability of CT and fluoroscopy and longer MR scan time, although may be used for anatomic delineation of leaks/fistulae when other modalities are equivocal | Frequently used in late pouch assessment. Superior tissue contrast and anatomic delineation of leaks. Can be combined with MRE for small bowel assessment when Crohn’s phenotype is suspected. |

| CT | Prefer IV contrast to assess for enhancing leak/fistula tracts. Can use contrast instilled directly into the pouch for leak visualization in early post-pouch patients with pelvic sepsis. | Often first-line modality for symptomatic immediate postoperative patients due to speed and availability. Excellent for assessment of most immediate postoperative complications such as pouch leaks, obstruction/ileus, and venous thrombosis. | In symptomatic patients in the late postoperative period, prefer CTE technique, particularly if a Crohn’s phenotype is suspected. |

| Plain Radiographs | May be used as a screening modality in acute postoperative patients | May be used if ileus or obstruction is suspected. | Limited utility. |

| Ultrasound | Has been described in the use of IBD and pouch imaging. | Requires specially trained sonographers and radiologists or clinicians. Evolving role, but currently with limited utility for routine pouch assessment. | |

Pouch anatomy

Since the initial description of the ileal pouch, surgical technique has evolved and refined. There are numerous iterations, including the J-pouch, S-pouch, W-pouch, D-pouch, and H-pouch, each utilizing a different configuration of the ileal reservoir in an attempt to optimize pouch function and continence while minimizing complications. The vast majority of pouch surgeries in the modern era are performed with J-pouch technique, due to a combination of a relatively more straightforward surgical approach and the lack of clear short-term or long-term benefits of more complex pouch configurations. ,

J-pouch creation involves folding the most distal segment of the ileum onto itself and stapling the 2 limbs together to form a single large caliber reservoir. The apex of the ileal reservoir is anastomosed to a short segment (should be <2 cm) of residual rectum located just above the anal sphincter; this rectal cuff is maintained to minimize the risk of damage to the internal sphincter intraoperatively, and because the anal transition zone has a physiologic role in preserving continence. Although historically IPAA was performed with either a handsewn anastomosis with mucosectomy of the remaining rectal mucosa or with a stapled anastomosis, the use of a stapled IPAA is associated with better long-term functional pouch outcomes without increased development of dysplasia within the residual rectal cuff mucosa. , Thus, a large majority of pouches are now created with a stapled IPAA, which is usually readily visible on fluoroscopy, MR imaging, and computed tomography (CT). J-pouch anatomy is detailed in Fig. 1 A–F , with several imaging landmarks outlined in Table 2 .

| Landmark | Definition | Imaging Appearance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis (IPAA) | Suture line anastomosing the ileal pouch to the rectal cuff | CT/fluoroscopy—radiodense chain suture line in the midline pelvis above the anal canal MR imaging—linear low signal, often best seen on precontrast and postcontrast T1-weighted fat-saturated images | Most common site of pouch leak. |

| Rectal Cuff | Segment of variable length of residual rectum between the anal sphincter and IPAA staple line. | Short segment below the IPAA suture line | Ideally 1–2 cm in length. Longer cuffs predispose patients to symptomatic cuffitis and may cause deficits in pouch emptying. |

| Pouch Body | Double-barreled reservoir that provides most of the capacity for stool retention | Comprises most of the pouch volume. Segment above the IPAA and below the pouch inlet and tip | |

| Pouch Tip | Blind-ending ileal segment comprised the most distal segment of ileum folded on itself. | Short ileal stump, usually at the most cephalad aspect of the pouch | Chronic pouch emptying dysfunction or chronic IPAA stricture may lead to dilation. Rare site of pouch leak. |

| Pouch Inlet | Ileal segment emptying into the pouch | 5 cm ileal segment just upstream of the proximal end of the longitudinal pouch staple line | Most mobile segment of the pouch, which may predispose the inlet to angulation, volvulus, and ischemia. |

| Afferent Limb | Distal ileum upstream of the pouch inlet | Normal-appearing ileum upstream of the pouch | |

| Pouch Mesentery | Mesentery of the ileal segment used to create the pouch | Fat and vascular pedicle of the pouch. Variable location that is surgeon dependent | Location is surgeon dependent. Anterior position may offer increased risk and decreased tension on the pouch, while posterior location may offer protection against volvulus and provide a cushion between the pouch serosa and presacral fascia. |

Imaging findings and pathology: J-pouch complications

Although the J-pouch has greatly improved the long-term quality of life in patients requiring proctocolectomy, it is a technically challenging procedure with a significant risk of complications. When considering postoperative pouch complications, it is helpful to consider the postoperative course in terms of early and late postoperative complications, although there can be considerable overlap in clinical presentation.

Early postoperative complications include those occurring within the immediate postoperative period and those within the variable period (usually several months) between pouch creation and loop ileostomy closure. Early complications include pouch leak leading to pelvic sepsis and more general postoperative complications such as ileus, obstruction, or portomesenteric venous thrombosis. Although patients with a pouch leak and pelvic sepsis may present with striking clinical symptoms, the presence of a diverting loop ileostomy may mask symptoms to some extent in a diverted pouch. A large meta-analysis of post-pouch complications showed that the most common early pouch complications were leak and postoperative ileus, both of which occurred in close to 20% of patients.

Late postoperative complications occur months to years after loop ileostomy closure. This encompasses a wide range of pathologies, including inflammatory conditions (pouchitis, cuffitis, chronic pouch leak, and development of a Crohn’s phenotype); mechanical pouch complications such as volvulus, twisted pouch, and IPAA anastomotic stricture; and functional pouch disorders leading to dyschezia or fecal incontinence. Because most pouches were created in patients with a predisposition to colonic malignancy (ulcerative colitis [UC] or familial adenomatous polyposis [FAP]), patients with pouch may rarely develop neoplasia, either within the pouch itself or within the rectal cuff. Late pouch complications are relatively common, with pouchitis occurring in up to 60% of patients, fecal incontinence in up to 20%, and pouch failure requiring pouch excision, usually associated with chronic pouch leak, occurring in up to 10% of patients at 10 years after pouch creation. ,

Early pouch complications

Anastomotic Leak

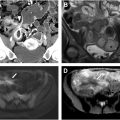

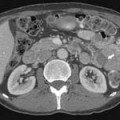

Pouch leaks occur in up to 19% of pouch patients leading to pelvic abscess, fistulae, and pelvic sepsis. Although leaks may occur at any location, the vast majority occur at the IPAA ( Fig. 2 A–F ). Early detection of leaks is essential to avoid chronic, pelvic sepsis that often leads to pouch excision.

In the acute setting, a water-soluble contrast enema is most commonly used for detection of IPAA leaks although MR imaging or CT (particularly CT with pouch contrast) may also be used when appropriate. Regardless of the modality, IPAA leaks are detected by first identifying the IPAA staple line and then identifying the extraluminal contrast extending from the staple line into the perianastomotic region. These leaks commonly extend into the presacral fat. When the anastomosis is handsewn, identifying these leaks can be more difficult, especially with a fluoroscopic, contrast enema. For a water-soluble contrast enema, it is critical to retract the catheter below the level of the staple line in order to avoid occluding the origin of the leak with the catheter. Multiple projections of the anastomotic area are essential in order to avoid obscuring a small leak with the contrast-filled pouch and cuff. Sometimes the radiologist may need to repeatedly empty and fill the pouch to detect subtle leaks. Lastly, reviewing a digital recording of the examination is essential, especially when differentiating a pouch-vaginal fistula from leaking of contrast from the anal verge and refluxing into the introitus.

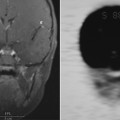

Pouch Tip Leak

Pouch tip leaks arise from the oversewn, blind-ending distal ileal segment (referred to by surgeons as the efferent limb; Fig. 3 A–D ). These are uncommon relative to IPAA leaks. While they have a similar impact on morbidity and pouch outcome, they are often missed and thus lead to sometimes years of suffering. Several studies have shown relatively poor performance of both imaging and pouchoscopy for detection of pouch tip leaks, , and a substantial number of pouch tip leaks may not be detected until after loop ileostomy closure (63% in one series ) leading to chronic pelvic sepsis and increased risk of pouch failure. With a fluoroscopic enema, the radiologist should attempt to visualize the tip. Unfortunately, this is often impossible as overlying bowel often obscures this area. Further, it is preferentially easier to fill the afferent limb (upstream toward the loop ileostomy) of the pouch first, before filling the blind end, efferent limb. Appearance on MR imaging and CT depends on the location of the tip, although pouch tip leaks frequently lead to a presacral sinus tract or abscess, which may fistulize to pelvic small bowel segments overtime. Anecdotally, MR is likely the best modality for identifying pouch tip leaks, especially those that are chronic.