INFECTIOUS AND NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISEASE: CHRONIC INFECTIONS INCLUDING FUNGAL

KEY POINTS

- Chronic infections usually have a different morphology of imaging studies than acute pyogenic infection, although overlap occurs.

- The magnetic resonance and computed tomography appearance of chronic infections and inflammatory conditions can mimic malignant neoplasms both solid and derived from hematopoietic cellular sources, granulomatoses, and histiocytoses.

- Invasive fungal disease spreads along vessels and in particular will follow arteries to produce unique findings that may help in the early diagnosis.

GENERAL MANIFESTATIONS

Soft Tissue Findings

Both acute and chronic osteomyelitis is essentially always bordered by soft tissue swelling. The typical inflammatory morphology of this soft tissue reaction is discussed in Chapter13 in conjunction with the basic pathophysiology and pathoanatomic correlates of infection and inflammation as seen on imaging studies. Chronic inflammatory changes may have the same general morphology on imaging studies as that described for cellulitis. This morphology is essentially a manifestation of edema and resultant swelling within the skin, subcutaneous and other fat, and muscles. Typically, chronic infection and inflammation have much less diffuse tissue swelling. In these more indolent processes, perilymphatic and more generalized fibrosis, which are part of both vascularized and nonvascularized scarring, may contribute substantially to the soft tissue changes. Sampling of such reactive tissue can lead to failure to diagnose or misdiagnose. The vascular response may be less brisk in the more chronic conditions, but this is really not predictable; its appearance is dependent on the point in the evolution of the disease sampled, whether there has been treatment, the immune status of the patient, and the inciting agent, among other factors (Figs. 16.1–16.4).

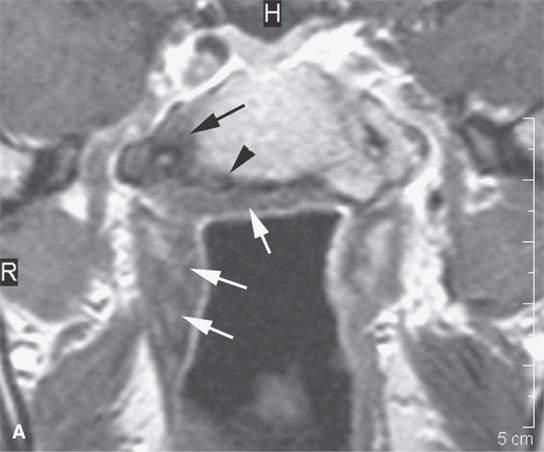

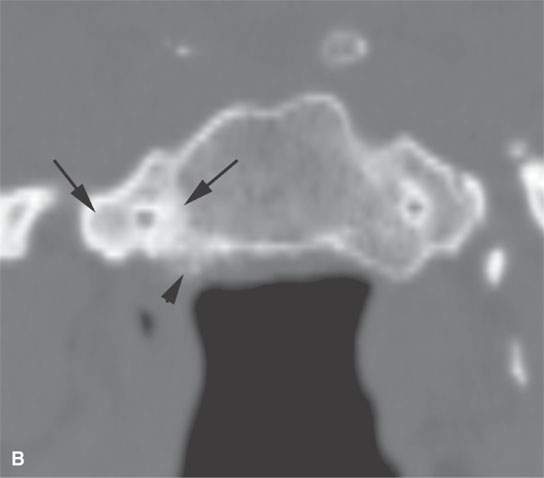

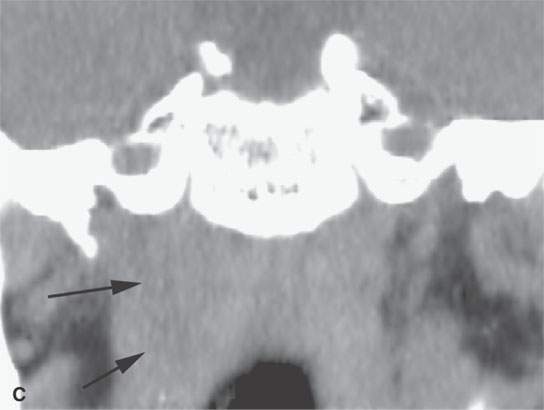

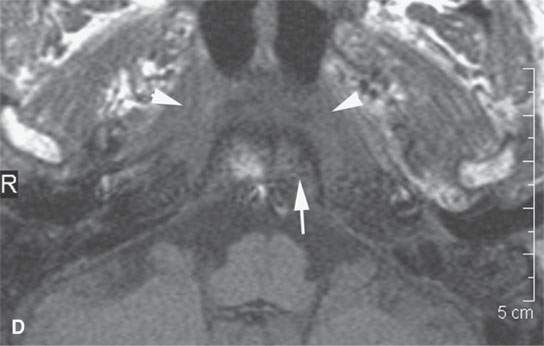

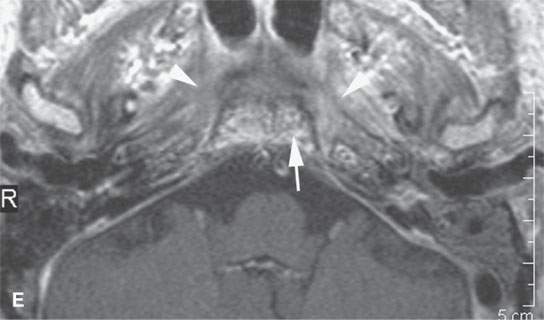

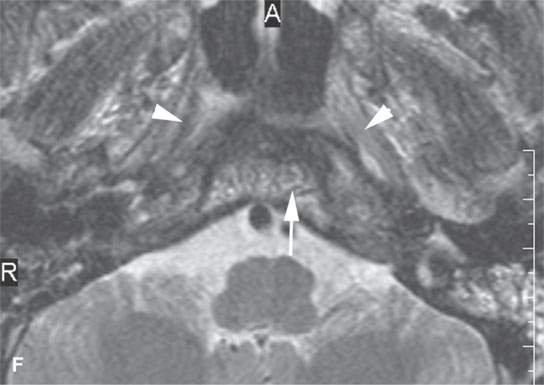

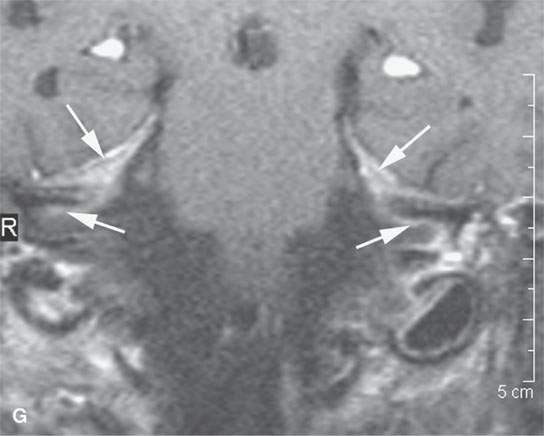

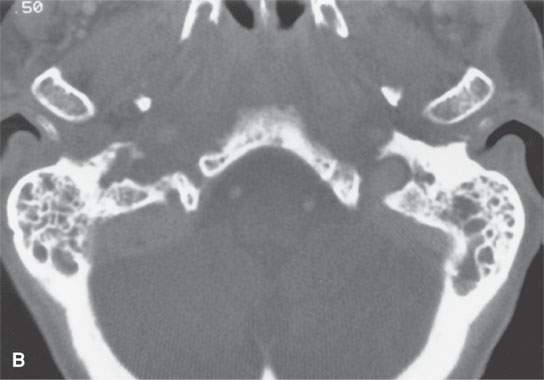

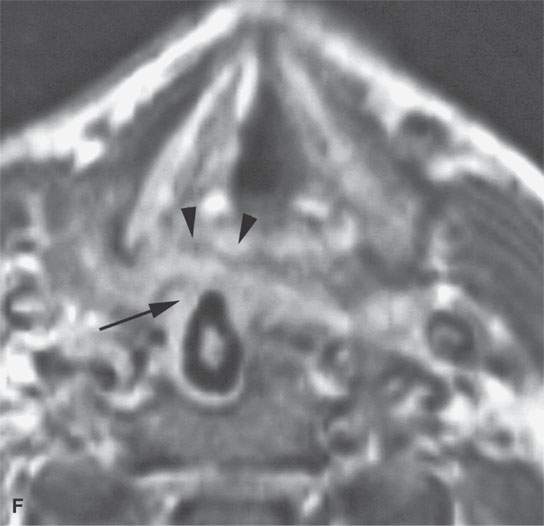

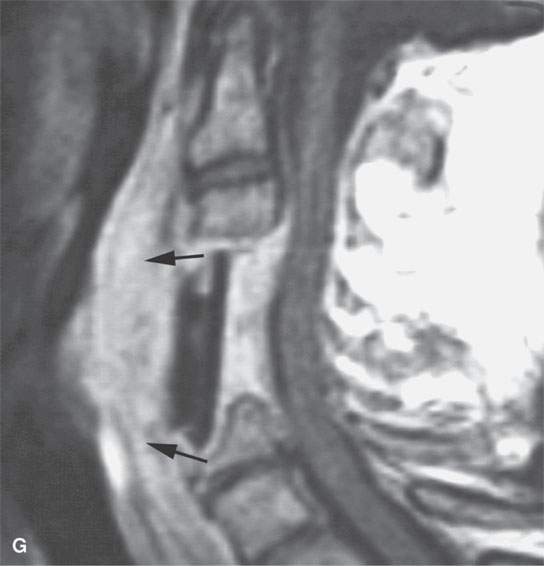

FIGURE 16.1. Patient with skull base osteomyelitis. T1-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance in (A) shows low signal in the marrow space of the clivus (arrow) and suggests reactive bony changes along its cortical surface. The soft tissue changes (white arrows) appear to have a significant fibrous reactive component. Computed tomography (CT) in (B) shows the dense reactive sclerosis (arrows) in the right side of the clivus compared to the left and the obvious chronic reactive periosteal thickening along its cortical surface (arrowhead). CT in (C) shows the related, nonspecific soft tissue thickening (arrows) compared to the magnetic resonance imaging. In a patient with skull base osteomyelitis, the non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image in (D) shows the usually fatty marrow space of the clivus (arrow) and the infiltration of surrounding soft tissues (arrowheads). The contrast-enhanced T1W (E) and T2-weighted fast spin echo (F) images show that the material in the clivus (arrow) and soft tissues (arrowheads) enhances and is actually less conspicuous on both sequences. Contrast-enhanced T1W image in (G) shows the related dural (arrows) component.

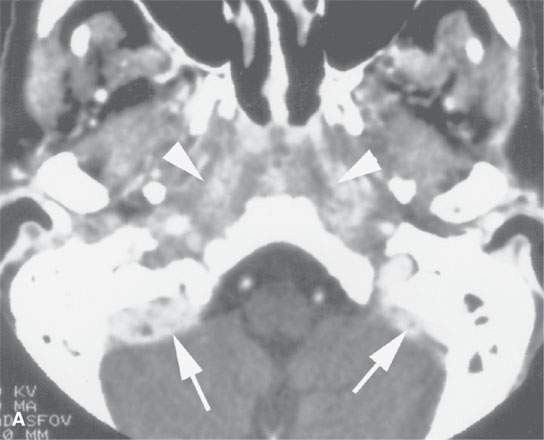

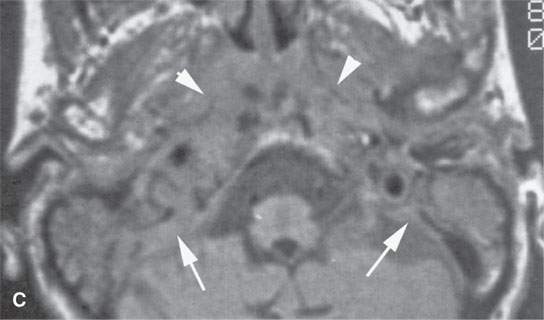

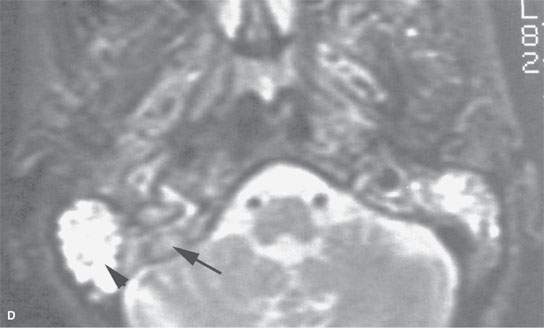

FIGURE 16.2. A patient with actinomycosis of the skull base. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) in (A) shows the obvious enhancement of diffusely infiltrating tissue in the nasopharynx (arrowheads) and the same tissue spreading intracranially, likely limited by the dura (arrows). The bone windows of the CT (B) are relatively noncontributory given the extent of the disease. The T1-weighted non–contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) image in (C) shows the extent of the disease in the peri-nasopharyngeal soft tissues (arrowheads) and intracranially (arrows), perhaps more graphically than the CT. The T2-weighted MR image was pivotal in care since it directed the neurosurgeon to the petromastoid junction (arrow) rather than the obviously brighter reactive mucosal thickening for tissue sampling.

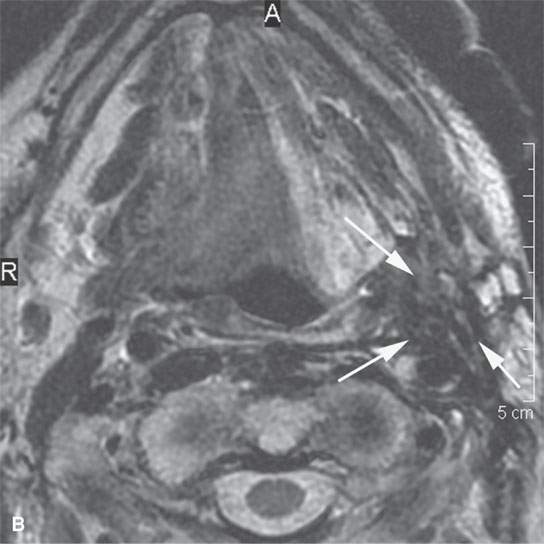

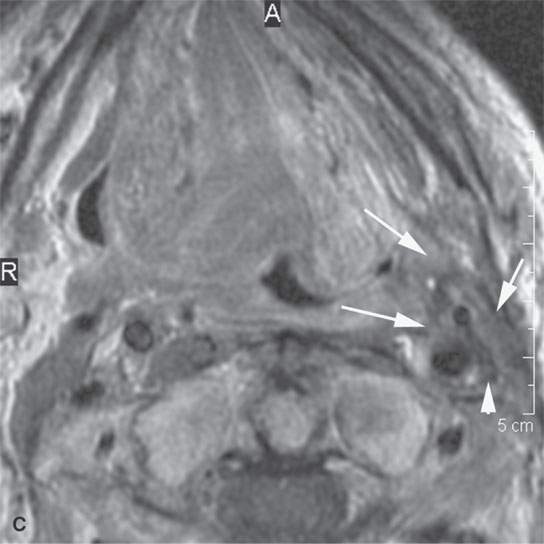

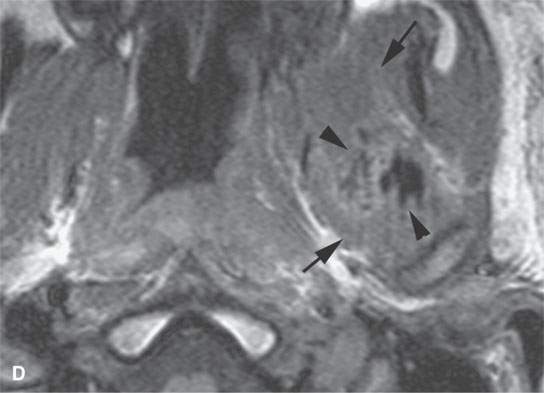

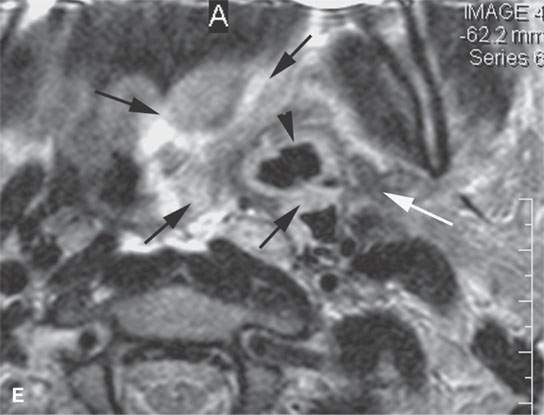

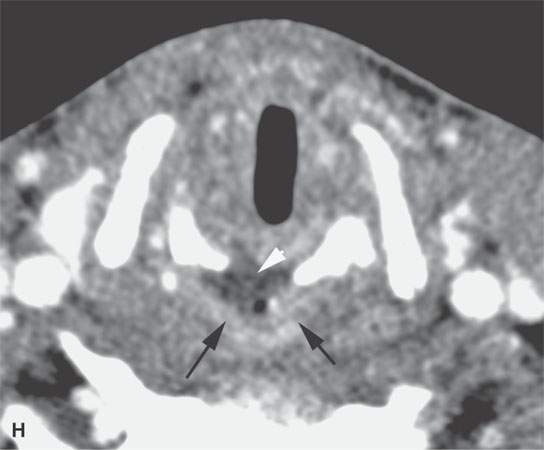

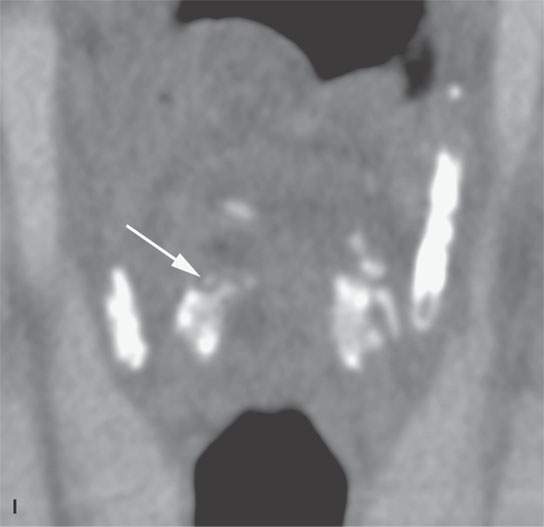

FIGURE 16.3. Four patients with chronic inflammatory conditions. For 4 years, the first patient complained of persistent pain following surgery and radiotherapy for a tongue base cancer. Multiple magnetic resonance imaging studies showed the same findings that follow. The non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) (A) and T2-weighted (T2W) (B) images shows muscle-equivalent signal intensity scarring (arrows). In the contrast-enhanced T1W image (C), most of the scar enhances (arrows) some of it less so (arrowhead). The second patient had a retained piece of fence post in the masticator space for about 6 weeks. The T1W image in (D) shows the foreign material (arrowhead) and some nondescript masticator space swelling (arrows) that is muscle equivalent in signal intensity. The T2W image in (E) shows extensive surrounding edema (black arrows), the foreign material (black arrowhead), and some early reactive fibrosis (white arrow). The third patient presented with dysphagia and was extruding a strut graft surrounded by enhancing, chronically infected granulation tissue. The T1W contrast-enhanced images (F, G) show the granulation tissue to be homogenously enhancing and bulging (arrows) into the posterior pharyngeal wall that was also thickened and inflamed (arrowheads in F). The fourth patient had a chronic burn injury to the upper airway resulting in dysphagia and chronic hoarseness without an obvious mucosal lesion due to chondritis. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography in (H) shows enhancing tissue (arrows) surrounding lower density, likely necrotic tissue (arrowhead). Coronal reformatted image (I) shows the eroded cricoarytenoid joint (arrow).

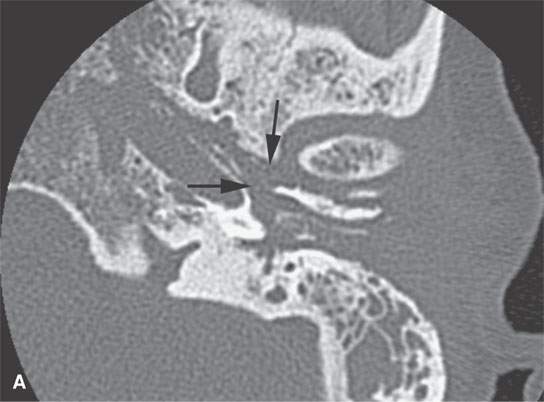

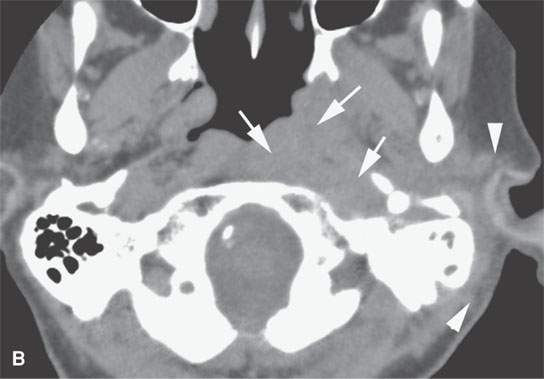

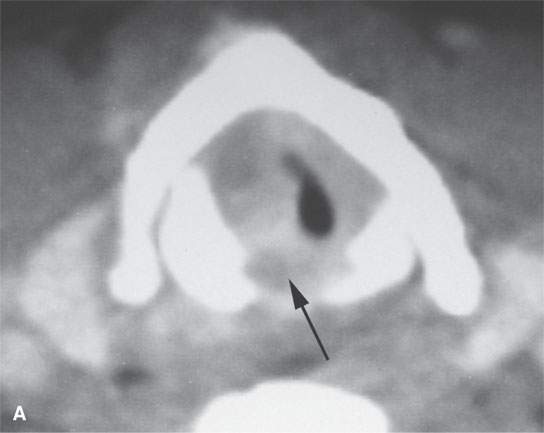

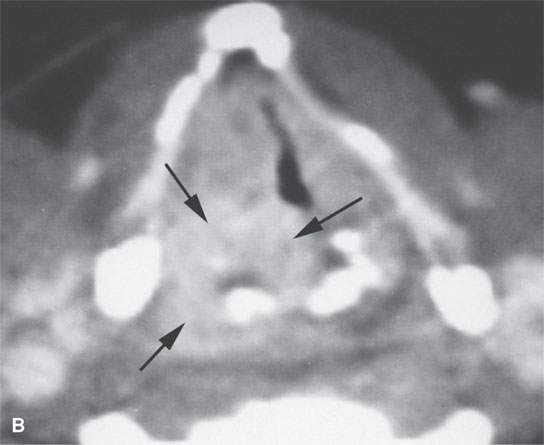

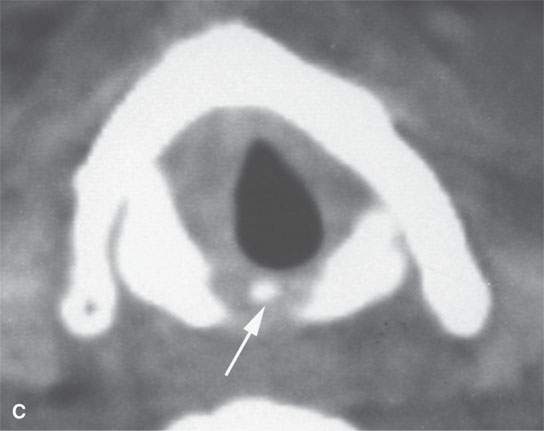

FIGURE 16.4. Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography study of a diabetic patient with necrotizing otitis externa due to pseudomonas infection. Bone windows in (A) show typical bone erosion along the petrotympanic fissure (arrows). The soft tissue involvement is for the most part fairly well defined (arrows in B), and there is considerable edema in the periauricular soft tissues (arrowheads), perhaps more than usually seen in the “average” nonbacterial chronic infectious process.

A typical example of such chronic soft tissue reactive changes is seen with chronic skull base osteomyelitis wherein the soft tissues bordering the infected bone are typically less edematous and likely more fibrotic in overall morphology than pyogenic cellulitis (Fig. 16.1).1,2 Such chronic infections with lesser degrees of soft tissue swelling are more likely to be fungal or due to more indolent organisms such as actinomycosis and spirochetes (Fig. 16.2). Chronic inflammation associated with scarring will typically show a significant fibrous component often mixed with vascularized scar (Figs. 16.1 and 16.3A–C). When skull base osteomyelitis is due to pseudomonas, there is usually more generalized surrounding edema and with a pyogenic organism even more swelling (Fig. 16.4) and more often than not a typical pattern of bone erosion. More importantly, the less exuberant variety of soft tissue changes seen in skull base osteomyelitis most often cannot be distinguished from infiltration of the soft tissues adjacent to bone by neoplasms such as leukemia, lymphoma, and plasmacytoma or chronic immune-mediated processes such as sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, and Langerhans histiocytosis (Fig. 16.5).

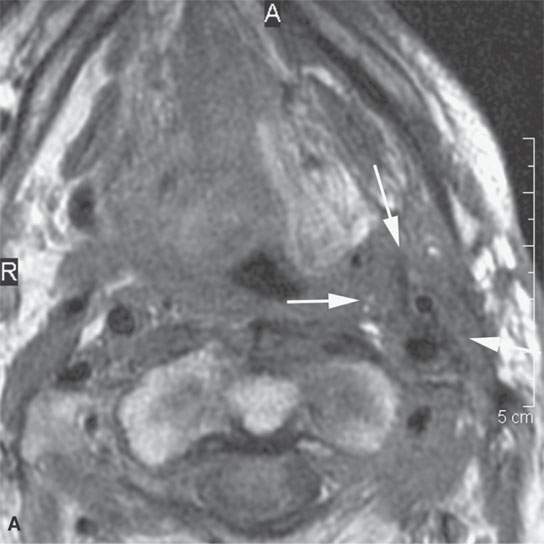

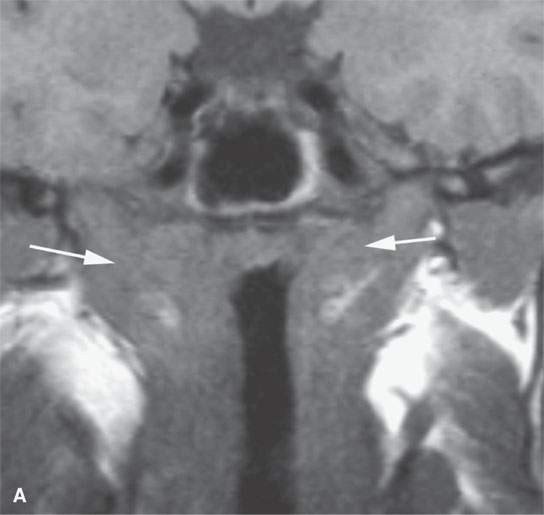

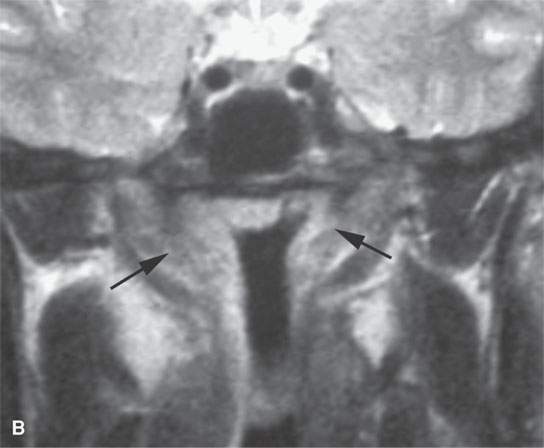

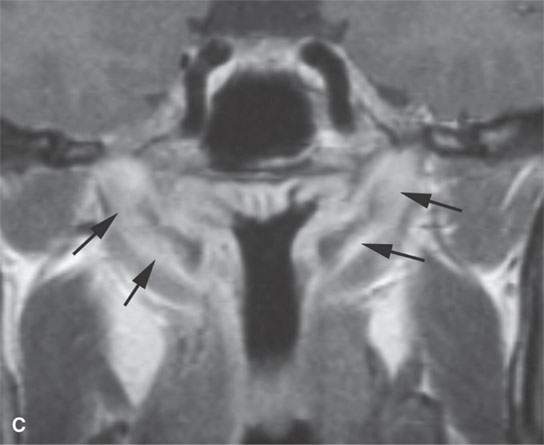

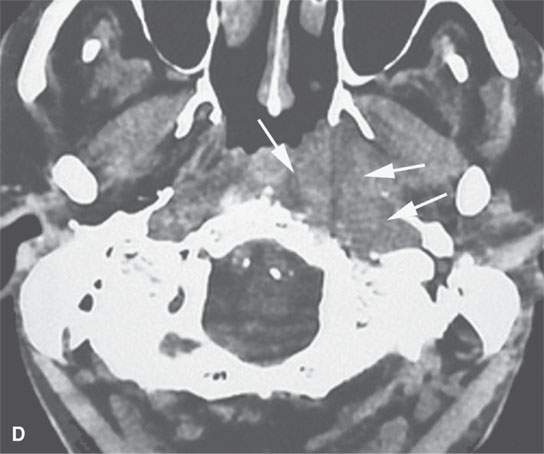

FIGURE 16.5. Two patients with disease that can mimic chronic infectious disease. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance in a patient with Wegener granulomatosis. Non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image in (A) shows infiltration of the deep tissue planes of the nasopharynx (arrows). T2W image in (B) shows these same areas to be edematous. In (C), there is extensive enhancement along the eustachian tubes (arrows). Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows an infiltrating extramedullary plasmacytoma of the nasopharynx (arrows).

Mucosal disease anywhere in the aerodigestive tract may be secondary to chronic aggressive infection that can be mistaken for malignancy (Fig. 16.6). Exuberant enhancement of the inflamed tissue with intravenous (IV) contrast is sometimes a clue that infection is a possibility; however, clinical features and ultimately biopsy are required for confirmation of infection as opposed to neoplasm (Fig. 16.7).3,4

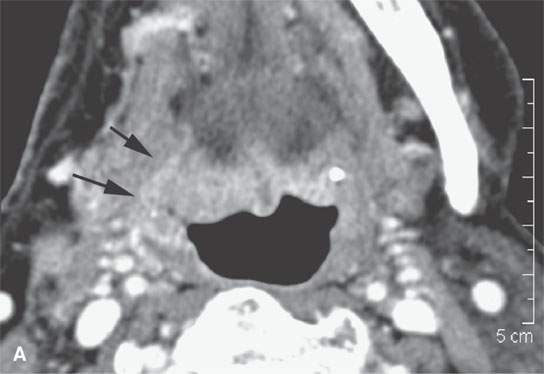

FIGURE 16.6. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography in a patient with right-sided otalgia and level 2 adenopathy. This chronic tonsillitis mimicked a cancer in that there is a suggestion of early deep infiltration in what is a primarily exophytic tissue (arrows) and enlarged nodes (arrowheads in B). All changes resolved on antibiotics. Biopsy showed only inflamed lymphatic tissue.

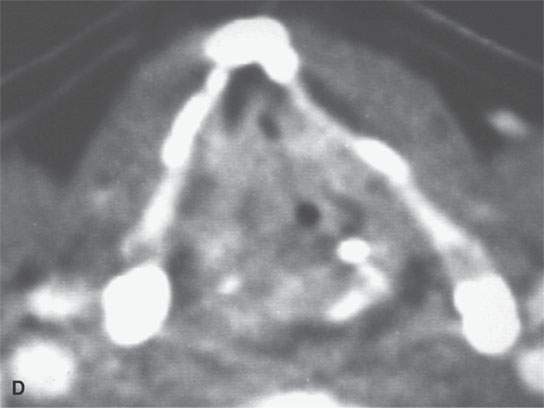

FIGURE 16.7. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography before (A, B) and after (C, D) penicillin therapy in a patient with laryngeal syphilis. Note the sequestrum in the eroded cricoid (arrow in C). The marked enhancement (arrows) before therapy was reported as atypical, and biopsy showed spirochetes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree