INFECTIOUS AND NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS: REACTIVE BONY CHANGES, OSTEITIS, OSTEONECROSIS, AND OSTEOMYELITIS

KEY POINTS

- Bony reactions and erosive changes are common to many different pathologic processes and sometimes critical to accurate diagnosis and medical decision making.

- Bone findings are best evaluated by computed tomography, but magnetic resonance and radionuclide studies are useful adjuncts in selected circumstances.

- Limitations of magnetic resonance imaging must be understood when bone findings are in the critical decision pathway.

Bone involvement is often a critical factor in the diagnosis and treatment planning of inflammatory, neoplastic, and other head and neck lesions. The bone may be the primary site of an inflammatory lesion, be secondarily involved, or be merely reacting to adjacent pathology in a manner that is not important in medical decisions. The bony pattern of involvement also serves as a general timetable of the pathologic process as well as a measure of the potential for aggressive behavior. These changes are best appreciated on computed tomography (CT) and plain films (Fig. 14.1) but can be noted on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 14.2) and in some cases, such as marrow space processes, are better appreciated with regard to their extent on MRI. Reactive bony changes tend to have a nonspecific appearance of variable increased tracer activity on radionuclide studies, but some differentiation is possible, given the appropriate clinical setting, with a combination of bone and gallium scanning (Fig. 14.3). Ultrasound has no value in evaluating such changes.

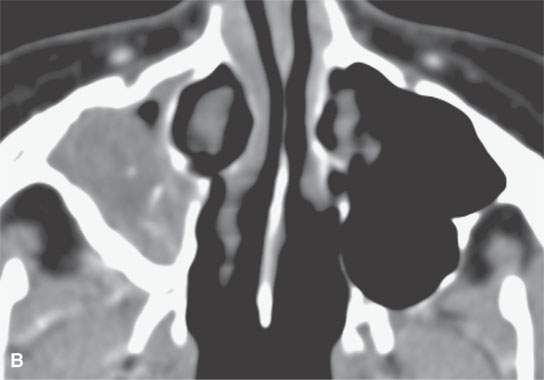

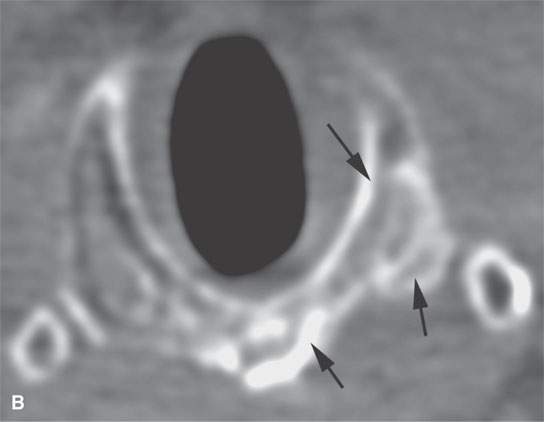

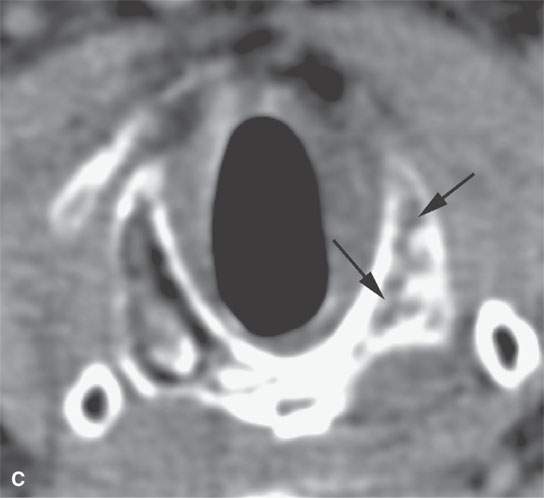

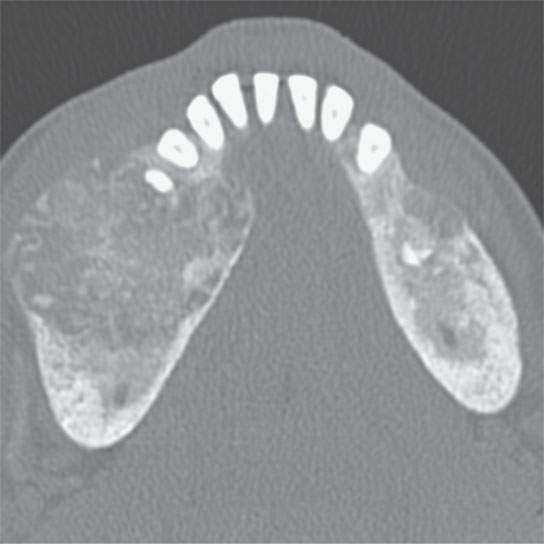

FIGURE 14.1. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis. Plain films (A) are not definitive but are suggestive of the disease. The computed tomography in (B) and (C) shows typical chronic periosteal reaction and cortical erosion.

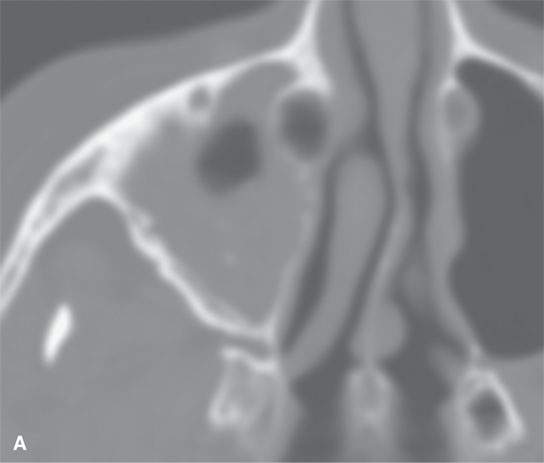

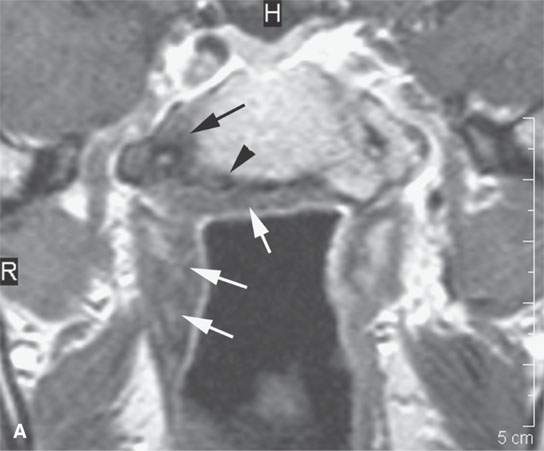

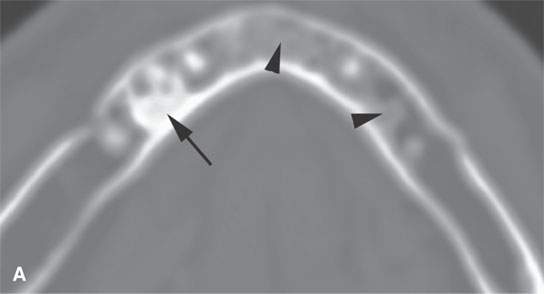

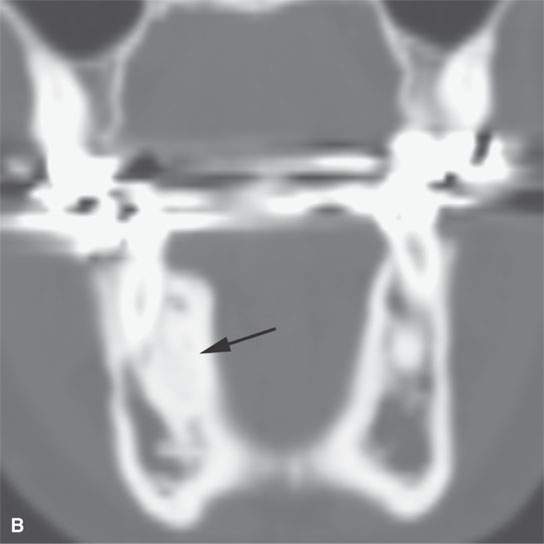

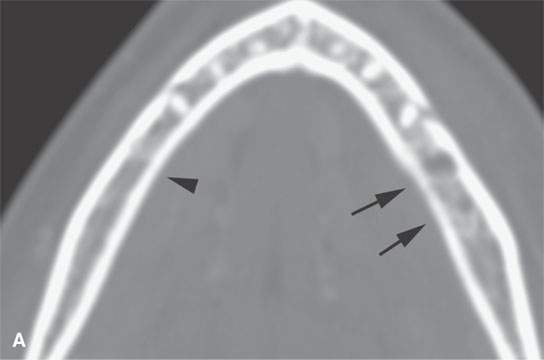

FIGURE 14.2. Patient with an inverted papilloma. Computed tomography (CT) section in (A) shows common reactive bony thickening (arrows) and erosion of the hard palate (arrowhead). The T2-weighted magnetic resonance image in (B) shows anterior skull base involvement (arrow) but not the hard palate erosion (arrowhead) or the reactive sclerosis. The CT in (C) shows anterior skull base erosion. The T1-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance in (D) suggests the anterior skull base involvement (arrow) but not related bone erosion and suggests hard palate erosion (arrowhead).

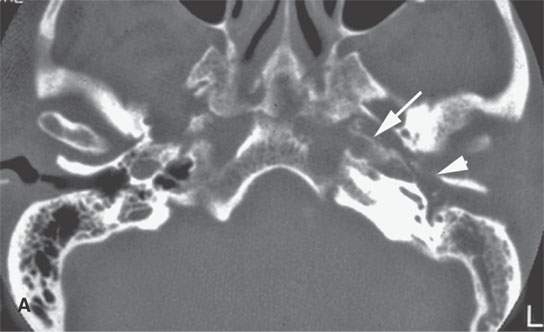

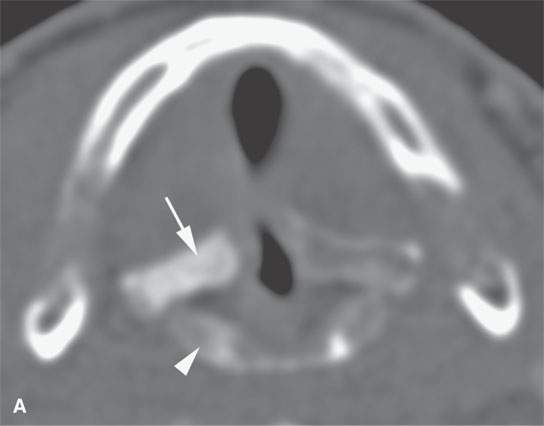

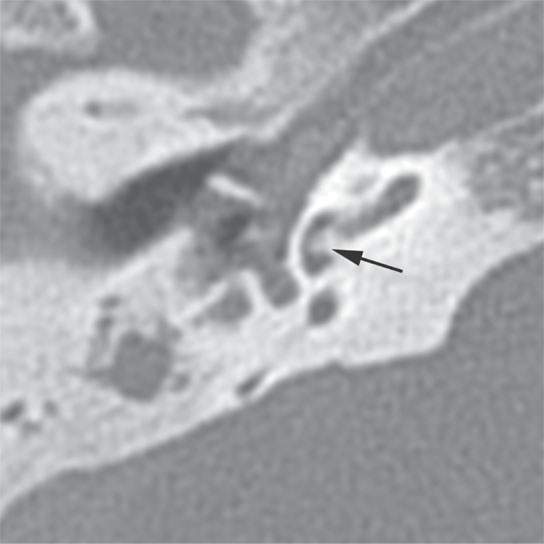

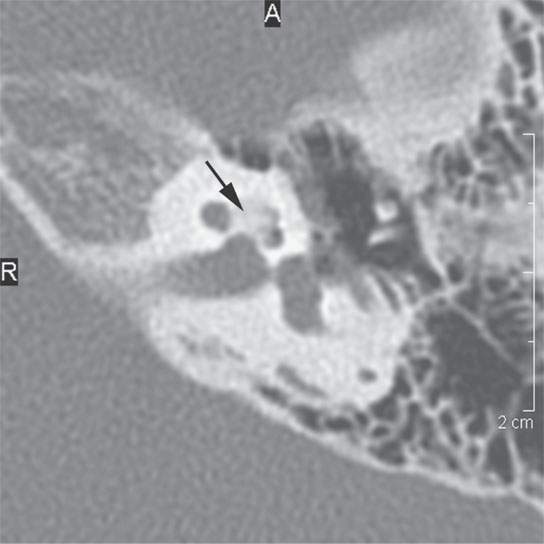

FIGURE 14.3. A diabetic patient with necrotizing otitis externa with computed tomography (A) showing erosion of the petrous (arrow) and tympanic (arrowhead) portions of the temporal bone. Bone/gallium single photon emission computed tomography images show markedly increased trace activity.

REACTIVE OSTEITIS

A chronic inflammatory mucosal origin process often produces sclerosis and thickening of the adjacent bone. Such a sclerotic reaction is probably most frequently present in the maxillary and sphenoid sinuses of patients with chronic recurrent or persistent sinusitis.1 It occurs in many circumstances, and this bony response is often called reactive osteitis (Fig. 14.4) or osteoneogenesis, but the bone reaction should not be confused with bone infection.2 The reactive new bone is only the result of chronic adjacent inflammation and/or infection and not actual infection of the bone.

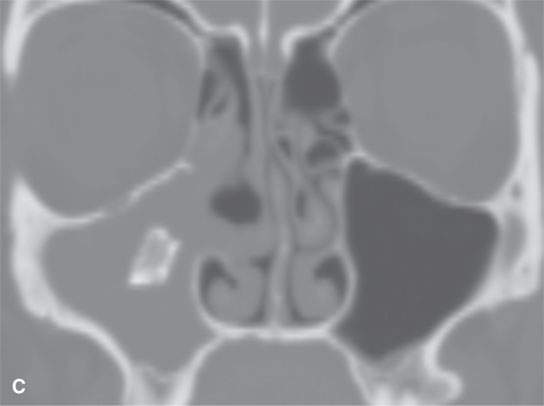

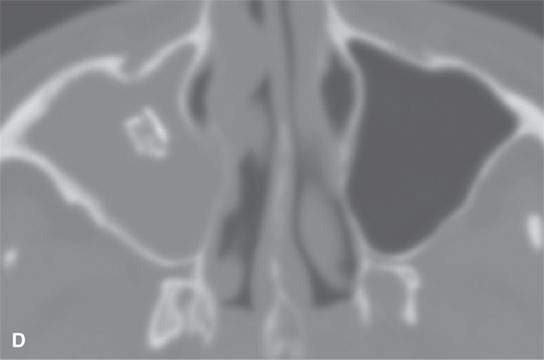

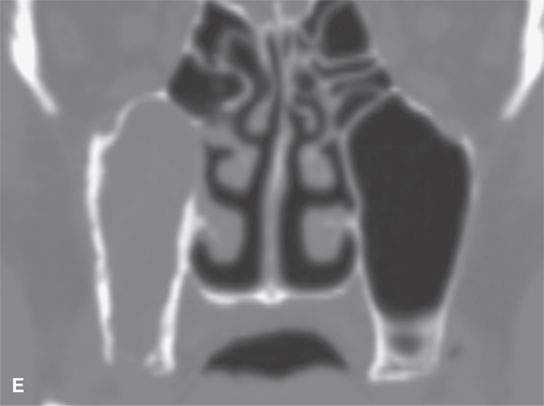

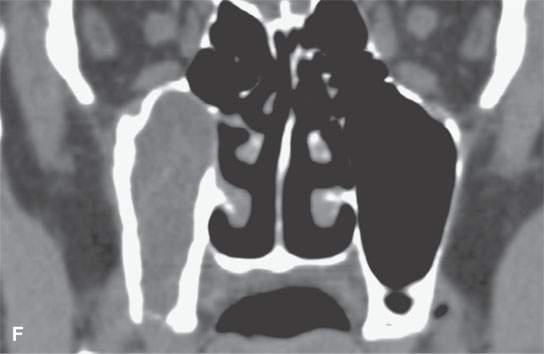

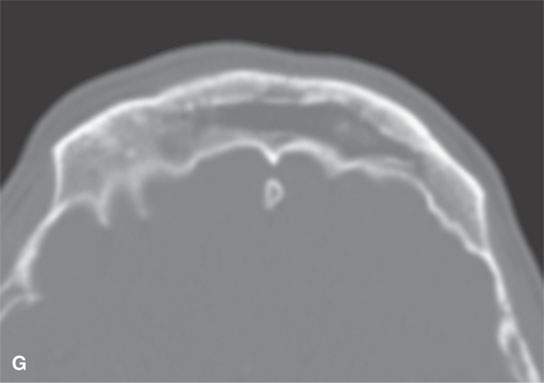

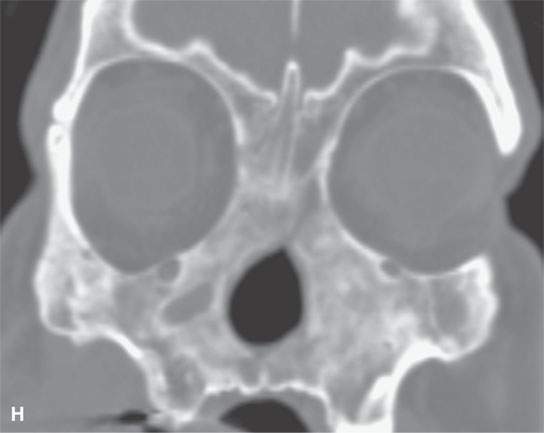

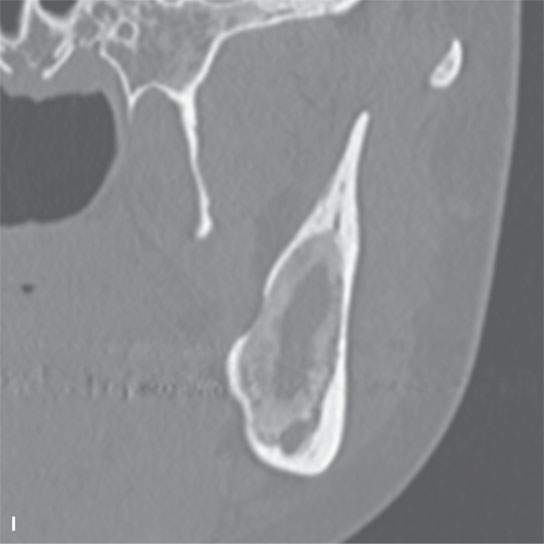

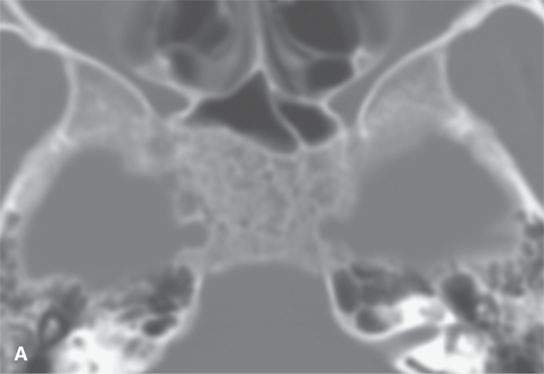

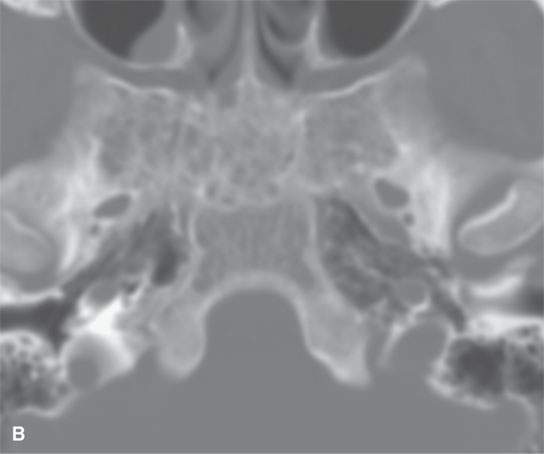

FIGURE 14.4. Computed tomography of various etiologies of reactive osteitis/bony sclerosis. A, B: Chronic sinusitis due to allergy and recurrent infections. C, D: Chronic sinusitis induced by a retained foreign body. E, F: Chronic sinusitis induced by an oral antral fistula. G: Reactive bone due to chronic sinusitis filling in the frontal sinus. H: Reactive bone filling in the sinuses and nasal cavity in a patient with long-standing Wegener granulomatosis. I: Reactive bone filling in a cavity left following curetting of an odontogenic keratocyst.

Thickening and sclerosis of bone in this setting is the result of slow, appositional growth of periosteal new bone (Fig. 14.4); if the process inciting the reaction is extensive and long-standing, it can become quite thick and obliterate a sinus lumen entirely. Occasionally, its appearance is useful in differential diagnosis. Reactive-appearing bone can also fill the cavity of bone lesions, and its appearance can mimic a matrix-producing process.

If the involved bone is trabecular, the trabeculae may become individually thickened and there will be concomitant crowding out of marrow in the spaces between the trabeculae, usually by a combination of reactive bone and fibroproliferative change (Fig. 14.5). This is seen in both the membranous and enchondral bones of the face and skull and in the ossified parts of the laryngeal skeleton as a reaction to inflammatory or neoplastic disease (Figs. 14.2, 2.14, and 4.14). Such changes are common in the mandible, where they are ubiquitous as areas of “condensing osteitis” in the marrow space surrounding the roots of teeth suffering from chronic periodontal and endodontal infections (Fig. 14.7) and in the mastoid air cells as the result of a long ago resolved chronic mastoiditis (Fig. 14.8).3 It is seen less commonly as an end-stage reactive change at other sites, such as the inner ear suffering obliterative labyrinthitis due to prior meningitis (Fig. 14.9).

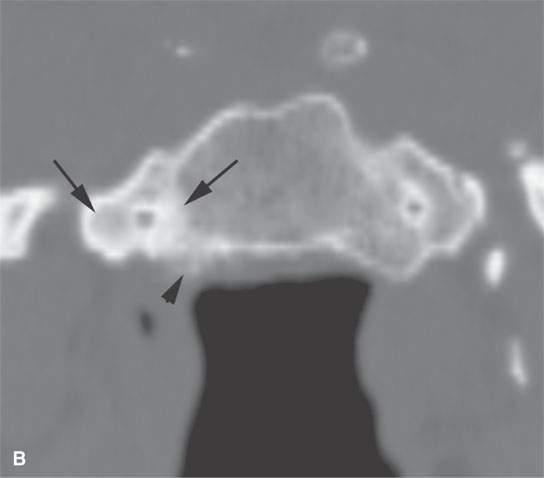

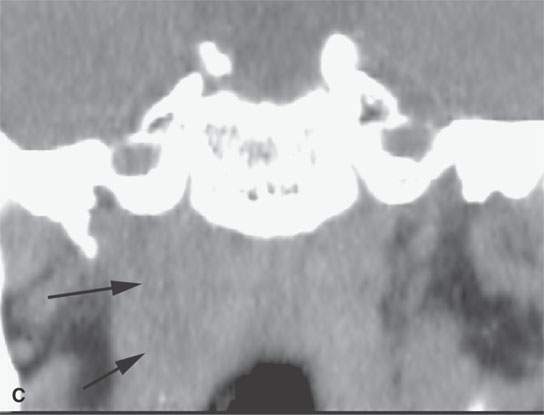

FIGURE 14.5. Patient with skull base osteomyelitis. T1-weighted contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance in (A) shows low signal in the marrow space of the clivus black (black arrow) and suggests reactive bony changes along its cortical surface (black arrowhead). The soft tissue changes (white arrows) appear to have a significant fibrous reactive component. The computed tomography (CT) in (B) shows the dense reactive sclerosis (arrows) in the right side of the clivus compared to the left and the obvious chronic reactive periosteal thickening along its cortical surface (arrowhead). CT in (C) shows the related, nonspecific soft tissue thickening (arrows) compared to the MRI.

FIGURE 14.6. Two patients with laryngeal cancer. The computed tomography (CT) in (A) shows the arytenoid cartilage (arrow) and top of the cricoid cartilage (arrowhead) to be sclerotic. This is caused by the adjacent cancer but does not necessarily indicate invasion. The CT of the second patient shows the left side of the cricoid cartilage to be sclerotic (arrows in B) and its marrow space to be infiltrated or reactive (arrows in C) on the left compared to the right. Fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) was positive, and biopsy and then surgery confirmed recurrent cancer with cartilage invasion.

FIGURE 14.7. Computed tomography of a patient with condensing osteitis (arrow in A and B) in the mandible—a common condition that can mimic tumor involvement on magnetic resonance. Here also are areas of lesser reactive sclerosis (arrowheads in A).

FIGURE 14.8. Computed tomography of a patient with chronic otomastoiditis and near-complete replacement of mastoid air cells by reactive bone as well as a focus of reactive fibro-osseous change in the vestibule (arrow).

FIGURE 14.9. Computed tomography showing reactive fibro-osseous obliteration of the cochlea due to prior meningitis.

Such bony changes can also be due to metabolic bone disease or other systemic diseases (Fig. 14.10) and should be recognized as such if the changes are more generalized than localized in the skull and/or face (Fig. 14.11).

FIGURE 14.10. Computed tomography showing reactive bony changes in the clivus and more lateral portions of the sphenoid bone related to marrow hyperplasia in a patient with sickle cell disease. Bone patterns can sometimes be a clue to the presence of systemic disease.

FIGURE 14.11. Computed tomography of two healing brown tumors of the mandible illustrate how the presence of more than one lesion associated with a bony reactive change may be associated with a systemic disease process.

OSTEOMYELITIS

The appearance and evolution of bone infections or inflammation will depend on the virulence of the inciting factor, host factors, blood supply, and treatment history.

Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Osteomyelitis

Both acute and chronic osteomyelitis are essentially always bordered by soft tissue swelling.1,4 The typical inflammatory morphology of this soft tissue reaction is discussed in conjunction with the basic pathophysiology and pathoanatomic correlates of infection and inflammation as seen on imaging studies in Chapter 13. In acute suppurative infections, there will very often be an associated subperiosteal or more extensive fluid collection (Fig. 14.12). More chronic soft tissue reactive changes, such as those seen with skull base osteomyelitis, usually are less edematous in overall morphology and cannot be distinguished from infiltration of the adjacent soft tissues by “small round cell neoplasms” such as leukemia, lymphoma, and plasmacytoma or chronic immune-mediated processes such as sarcoidosis (Chapter 18), Wegener granulomatosis (Chapter 17), and Langerhans histiocytosis (Chapter 19),2 all discussed and illustrated subsequently in the indicated chapters dedicated to these specific diseases. Such changes in bone due to matrix-producing tumors (Chapter 12), metastases (Chapter 42), and primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Chapter 188) can also mimic or be mimicked by infection (Fig. 14.13). Such chronic skull base infections are more likely to be fungal or due to more indolent organisms such as actinomycosis.

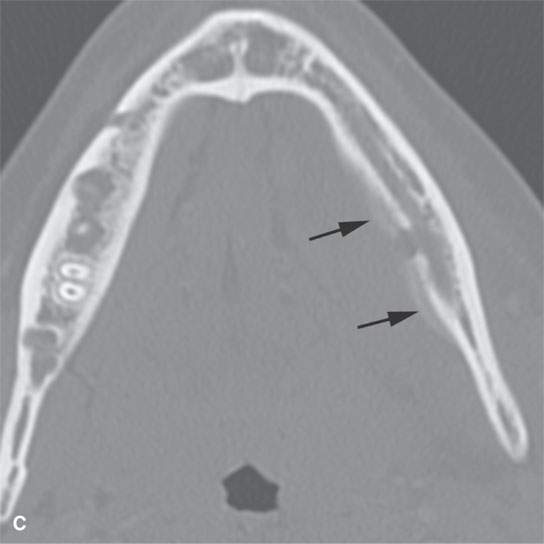

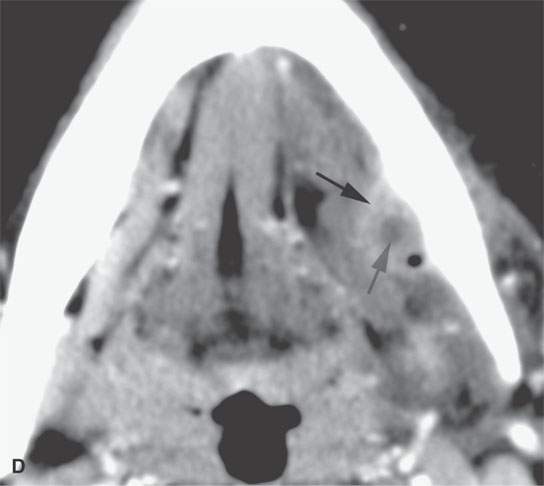

FIGURE 14.12. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography studies of two patients with acute/subacute osteomyelitis of the mandible. There is periosteal bone erosion (arrow in A) compared to the normal side (arrowhead) in one patient with a subperiosteal abscess (arrow in B). The second patient has a cortical abscess with periosteal reaction (arrows in C) and related phlegmon and abscess cavity shown in (D) (arrows).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree