Etiology

Colonic inflammation may be caused by numerous processes and is typically thought of as colitis. Some inflammatory conditions of the colon such as diverticulitis and epiploic appendagitis also represent inflammatory lesions of the colon and, on occasion, may be difficult to distinguish from each other and from neoplastic conditions.

Colitis may be due to infection, autoimmune processes (Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis), ischemia (low flow, emboli, vasculitides), irradiation, direct toxic insults, chronic abuse of cathartic agents, and intrinsic pathologic inflammatory conditions such as diverticulitis and epiploic appendagitis.

In the case of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis, ongoing activation of the mucosal immune system is thought to represent the underlying cause. There are numerous stimulants to the activation of this abnormal autoimmune process in patients with Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, but both genetic and environmental factors are important. Infectious colitis may be due to bacteria, parasites, or viruses. The patient’s underlying immune status is important to know when considering the differential diagnosis of infectious colitis. In addition to typical infectious agents that may cause colitis, persons with altered immunity are at risk for opportunistic infections. A history of recent travel and food ingestion can be helpful when considering infectious causes. Although certain imaging findings are helpful in the differential diagnosis, they are often nonspecific in the case of infectious colitis, and culture of the stools is often necessary to determine the exact cause of infectious colitis. Additionally, direct toxin or pathologic abnormality may be the cause of the colonic inflammation. In this chapter the focus is on the imaging findings and differential diagnosis of nonischemic causes of colonic inflammation.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The prevalence of colonic inflammation is related to the cause of the process and the age of the patient. Ulcerative colitis affects 10 to 12 in 100,000 individuals in the United States, with the peak incidence occurring between ages 15 and 25 years. The prevalence of Crohn’s disease is similar, affecting up to 20 to 40 to 100,000 individuals of Northern European descent. Although most patients with these conditions are young, there is a bimodal age distribution with a second peak in older individuals.

Diverticular disease affects up to 10% of the population older than the age of 50, and up to 20% of these patients will develop symptomatic diverticulitis. Infectious colitis can affect anyone, but is very common in immunocompromised individuals. Other forms of colonic inflammation including stercoral colitis, epiploic appendagitis, cathartic colon, and glutaraldehyde colitis occur much less frequently.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The prevalence of colonic inflammation is related to the cause of the process and the age of the patient. Ulcerative colitis affects 10 to 12 in 100,000 individuals in the United States, with the peak incidence occurring between ages 15 and 25 years. The prevalence of Crohn’s disease is similar, affecting up to 20 to 40 to 100,000 individuals of Northern European descent. Although most patients with these conditions are young, there is a bimodal age distribution with a second peak in older individuals.

Diverticular disease affects up to 10% of the population older than the age of 50, and up to 20% of these patients will develop symptomatic diverticulitis. Infectious colitis can affect anyone, but is very common in immunocompromised individuals. Other forms of colonic inflammation including stercoral colitis, epiploic appendagitis, cathartic colon, and glutaraldehyde colitis occur much less frequently.

Clinical Presentation

Most patients with colonic inflammation present with crampy abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis, and some form of change in bowel habits. The change in bowel habits is usually diarrhea. Diarrhea may be bloody or nonbloody and is related to the type of inflammation. Although the clinical presentation, nature and frequency of the diarrhea, age of the patient, and other epidemiologic factors may indicate a particular type of colonic inflammation, laboratory testing, cross-sectional imaging, endoscopy with biopsy, and culture of the stool are critical in establishing the correct diagnosis.

Pathophysiology

When considering the imaging findings that help narrow the differential diagnosis of a pathologic colonic inflammatory condition, several factors are important. These include the length of involvement, location of involvement, degree of thickening, and extraintestinal manifestations of the disease. By carefully considering these anatomic considerations the differential diagnosis can be considerably narrowed.

Imaging

General Considerations

Because the clinical manifestations of patients with colonic inflammation are broad and overlap with other colonic diseases, a patterned approach using several key observations can help narrow the differential diagnosis.

Length of Involvement

The length of diseased colon is important in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Certain entities tend to be focal, segmental, or diffuse.

Focal Disease (2 to 10 cm)

- •

Neoplasm

- •

Diverticulitis

- •

Epiploic appendagitis

- •

Infection (tuberculosis/amebiasis)

Segmental Disease (10 to 40 cm)

- •

Usually colitis

- •

Crohn’s colitis

- •

Glutaraldehyde colitis

- •

Ischemia

- •

Infection

- •

Ulcerative colitis (typically begins in the rectum and spreads proximally)

- •

- •

Rarely neoplasm (especially lymphoma)

Diffuse Disease (Most of the Colon)

- •

Always benign

- •

Infection

- •

Ulcerative colitis

- •

Vasculitis (almost always involves the small bowel as well)

- •

Location of Involvement

Whereas almost any pathologic condition can affect any area of the colon, some pathologic entities have a propensity to localize to certain areas of the colon.

Cecal Region

- •

Amebiasis

- •

Typhlitis (neutropenic colitis)

- •

Tuberculosis

Isolated Splenic Flexure and Proximal Descending Colon

- •

Watershed area for low-flow intestinal ischemia

Rectum

- •

Early stages of ulcerative colitis

- •

Stercoral colitis

Multiple Skip Regions

- •

Crohn’s disease

Degree of Thickening

There is significant overlap in the degree of colonic wall thickening among different colonic pathologic processes. Mild thickening may be seen in plaque-like tumors and mild colonic inflammation. Marked colonic thickening greater than 1.0 to 1.5 cm may be seen in pseudomembranous, tuberculous, and cytomegaloviral colitis, as well as colonic neoplasms and vasculitis. Occasionally, the degree of thickening and the imaging appearance of colon cancer and diverticulitis may overlap ( Figures 31-1 and 31-2 ). In both cases the disease is usually focal or involves a short segment of colon and may be associated with marked thickening of the bowel wall. Inflammatory changes in the mesentery have been shown to favor the diagnosis of diverticulitis, and adjacent lymphadenopathy has been shown to favor colon cancer. However, because there is considerable overlap in the degree of thickening of different colonic pathologic processes, overall the degree of thickening has limited value in itself for narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Pattern of Enhancement

The pattern of enhancement can be important in discriminating different forms of intestinal pathology.

Target and Double Halo

- •

Edema

- •

Infection, inflammation (ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis), ischemia, vasculitis

- •

- •

Submucosal fat

- •

Chronic inflammation

- •

Normal variant

- •

- •

Neoplasm

- •

Rarely scirrhous carcinoma of rectum

- •

Homogeneous

- •

Neoplasm, chronic inflammation

Heterogeneous

- •

Neoplasm

Diminished

- •

Ischemia

Extraintestinal Manifestations

When an abnormal segment of colon is evaluated, the adjacent mesentery, presence and attenuation of abdominal lymph nodes, and status of the vasculature must be assessed. Abnormalities pertaining to these structures can be helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Low-attenuated lymph nodes are often associated with tuberculosis. Mesenteric changes including fibrofatty proliferation, sinus formation, and hyperemia in the vessels subtending an abnormal segment suggest Crohn’s disease. Filling defects in the vessels suggest colonic ischemia.

Radiography

The hallmark of acute colonic inflammation on radiographs of the abdomen is the “thumbprinting” sign ( Figure 31-3 ). This finding represents thickened haustral folds with intracolonic gas outlining the thickened haustral folds. This is a nonspecific finding and is related to edema in the colonic submucosa. This finding correlates with the “double halo” or “target” sign that is seen on computed tomography (CT). Thumbprinting on radiographs and the double halo sign on CT may be seen in any form of acute colonic inflammation, including infection, ischemia, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and vasculitis.

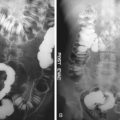

Another finding that may be present on radiographs and may suggest a specific diagnosis is an ahaustral colon. On imaging, this manifests as a featureless tubular appearance of the colon. This is usually seen in the descending colon and represents chronic scarring that may be seen in ulcerative colitis and rarely in cathartic colon ( Figure 31-4 ).

Finally, plain radiographs of the abdomen may show small filling defects in the colon ( Figure 31-5 ). The differential diagnosis includes a polyposis syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis and postinflammatory pseudopolyps in the colon, which may be seen in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Other than these imaging findings, radiographs of the abdomen are of limited utility in the evaluation of colonic inflammation.

Barium studies of the colon used to be the primary noninvasive imaging technique to evaluate the colon in case of colonic inflammation. However, CT and endoscopy are now the primary imaging techniques to evaluate the patient with colonic inflammation.

Computed Tomography

Normal Colon

CT is the primary imaging tool used to evaluate patients with abdominal pain and suspected colonic disease. There are three main findings on CT that correlate with colonic inflammation: colonic wall thickening, mural stratification (“target” sign) after intravenous contrast administration, and pericolonic fat stranding.

The normal colonic wall is thin, measuring between 1 and 2 mm when the lumen is well distended. However, there is considerable variation in the thickness of the normal colonic wall depending on the degree of luminal distention. It is not unusual for the wall of the normal colon to measure up to 5 mm in the supine position and 1 mm in the prone position and vice versa. As a result, different criteria have been used to diagnose colonic wall thickening.

Frequently, because of internal fecal contents, fluid, or colonic redundancy the true thickness is difficult to ascertain. This is most true for the sigmoid colon and is a location where bowel wall thickening is often “over-called” on CT. In these cases, carefully following the colonic wall to a region where the colon is well distended with gas will often demonstrate the true thickness of the wall ( Figure 31-6 ). Observing the enhancement pattern and changes in the pericolonic fat are also helpful in determining whether the bowel is truly abnormal.

Typically, no specific colonic preparation is used when performing routine abdominal and pelvic CT. However, if there is a concern regarding the true thickness of the colonic wall, insufflation of the colon with room air via a small rectal catheter can be helpful in revealing the true thickness.

The normal colonic wall enhances after an adequate intravenous bolus of contrast agent has been administered. When abdominal CT is performed, a 20- to 22-gauge catheter should be inserted into an arm vein and 1.5 to 2.0 mL/kg of iodinated contrast agent (270-370 mgI/mL concentration) should be injected at a rate of at least 2.5 to 3.0 mL/s. Enhancement is usually greater on the mucosal aspect of the bowel wall. This enhancement should not be mistaken as a pathologic process. Recognizing that the wall is not thickened and that no perienteric inflammation is present will allow one to differentiate normal enhancement from a pathologic process. If an intravenous contrast agent is not administered, significant colonic pathologic processes may be overlooked ( Figure 31-7 ).

Multiplanar images can be extremely helpful when evaluating the bowel because of the redundant nature of both the small bowel and colon.

Specific Pathologic Causes of Colonic Inflammation

The hallmark of inflammation at CT is the “double halo” or “target” sign ( Figure 31-8 ). The target sign was first described as a specific sign for Crohn’s disease, but it is now recognized that any non-neoplastic condition may lead to a target appearance in the small bowel or colon ( Figures 31-9 to 31-12 ). Rarely, infiltrating scirrhous carcinomas of the stomach or colon may display a target or double-halo appearance at CT. It may be difficult to distinguish rectosigmoid inflammation from an infiltrating neoplasm ( Figure 31-13 ). Although infiltrating scirrhous type neoplasms frequently show marked thickening, adjacent adenopathy, and an abrupt transition, a high index of suspicion is necessary to consider this in the differential diagnosis.