(1)

Princess Elizabeth Hospital Le Vauquiedor St. Martin’s Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK

(2)

Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, England UK

Abstract

Mastitis is an inflammatory condition of the breast, which may or may not be accompanied by infection (WHO 2000). The condition is usually associated with lactation, the so-called lactational mastitis (Kvist et al. 2008; Scott et al. 2008) but can also arise in non-lactating women. Mastitis is defined as a red, tender, hot, swollen area of the breast, accompanied by one or more of the following:

Learning Points

Milk stasis is the main predisposing factor of lactational mastitis.

Lactational breast abscesses are initially treated conservatively with aspiration and antibiotics and refered for surgery if conservative management fails.

If not treated appropriately, lactational breast abscesses can recur and may be complicated by a fistulous tract.

Duct ectasia is characterised by inflammation and dilation of the major ducts.

Possible aetiological factors of duct ectasia include infections and cigarette smoking.

Complications of duct ectasia include abscess formation, fistulous tract and nipple retraction.

Associated fibrosis and calcification in duct ectasia can simulate breast cancer.

Diabetic mastopathy is a rare condition mostly reported in women with Type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Diabetic mastopathy is thought to be an autoimmune disease characterised by keloid-type fibrosis and lymphocytic lobulitis.

There is no risk of progression to malignant lymphoma in patients with diabetic mastopathy.

Diabetic mastopathy has a tendency to recur in the ipsilateral or contralateral breast.

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) can mimic an abscess and should be considered if treatment for breast abscess fails.

IGM simulates cancer clinically and radiologically.

Preoperative pathological diagnosis of IGM is essential to avoid unnecessary mastectomy.

6.1 Mastitis and Breast Abscess

6.1.1 Mastitis

Mastitis is an inflammatory condition of the breast, which may or may not be accompanied by infection (WHO 2000). The condition is usually associated with lactation, the so-called lactational mastitis (Kvist et al. 2008; Scott et al. 2008) but can also arise in non-lactating women. Mastitis is defined as a red, tender, hot, swollen area of the breast, accompanied by one or more of the following:

(i)

An elevated temperature (either estimated or measured as being over ≥ 38 °C)

(ii)

One or more of the constitutional symptoms of fever, body aches, headaches and chills

6.1.2 Incidence of Lactational Mastitis

The incidence of mastitis varies in each country and the publications tend to be on selected cases. In population-based studies in Australia where breastfeeding initiation is over 80 % and approximately 50 % of women breastfeed for 6 months (Donath and Amir 2005), the incidence of mastitis is reported to be 15–20 %, 6 months postpartum (Kinlay et al. 1998; Brown and Lumley 1998). In a large cohort study from Australia, 1,193 women were assessed 6 months postpartum and 217 (17 %) reported mastitis and five developed an abscess (Amir et al. 2004). Approximately 10 % of women experience postpartum mastitis in the USA (Foxman et al. 2002). In a prospective cohort study in Glasgow UK, the authors reported lactational mastitis in 74 (18 %) out of 420 breastfeeding women (Scott et al. 2008).

6.1.3 Causes of Lactational Mastitis

Milk stasis and infection are the main causes of lactational mastitis. Milk stasis is a significant factor in initiating mastitis. Thomsen and colleagues (1984) reported that a raised white cell count and bacteria in the milk of infectious mastitis improved with removal of milk than with antibiotics. Milk stasis occurs when the breasts are engorged soon after delivery or when the infant does not breastfeed effectively due to ineffective suckling, restriction of the frequency or duration of feeds and blockage of milk ducts (WHO 2000). The baby should be well attached to the breast for effective removal of milk. Poor attachment to the breast causes fissured nipples and pain (Woolridge 1986). Sore nipples and pain leads to avoidance of breastfeeding with further milk stasis (Fetherston 1998). A short frenulum (tongue-tie) in the infant causes sore and fissured nipple reduces the efficiency of milk removal (Marmet et al. 1990).

Maternal fatigue, stress, anaemia, poor nutrition and maternal or infant illness have all been associated with mastitis (WHO 2000). The main cause of infectious mastitis is coagulase negative S. aureus, which are the bacteria frequently cultured in milk (WHO 2000). S. albus, E. coli and Streptococci have all been isolated from milk (WHO 2000). A nipple fissure is the most likely port of entry (Masaitis and Kaempf 1996). Many lactating women have potentially pathogenic bacteria on their skin or in their milk, but many women who do develop mastitis do not have pathogenic organisms in their milk (WHO 2000).

Mastitis should be treated urgently and the focus is on reversing milk stasis, maintaining milk supply, continuing breastfeeding and ensuring maternal comfort (WHO 2000). Mothers with acute pain, severe symptoms and/or fever need prompt antibiotic treatment, irrespective of whether the mastitis is presumed infectious or not (Betzold 2007).

6.1.4 Lactational Breast Abscess

If lactational mastitis is not treated promptly, this will lead to a breast abscess. Breast abscesses develop as a complication of mastitis in 5–11 % of the patients (Amir et al. 2004). The most common causative organism is S. aureus (Trop et al. 2011). This type of abscess affects up to 65 % of primiparous mothers and responds well to drainage and antibiotics (Ulitzsch et al. 2004; Dener and Inana 2003).

6.1.5 Non-lactational Breast Abscess

Breast abscesses that occur outside the breastfeeding period are classified according to location, either central (peri-areolar) or peripheral (Trop et al. 2011). Non-lactational abscesses affect more black women than white (Benson 1989). Other risk factors include obesity, cigarette smoking and diabetes mellitus (Benson 1989; Rizzo et al. 2010).

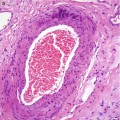

Central (peri-areolar) non-lactational abscesses are the most common form of abscesses that develop outside the breastfeeding period (Trop et al. 2011). They affect mostly young women who smoke (Bharat et al. 2009). The abscesses arise as a complication of periductal mastitis. Initially there is squamous metaplasia of the cuboidal epithelium of the lactiferous ducts which leads to formation of keratin plugs followed by acute inflammation and cellular debris which distend and obstruct the ducts, leading to dilatation. Stagnation predisposes to secondary infection leading to development of an abscess (Fig. 6.1) which may be complicated by a fistula as a way of releasing the pressure from the pus distending the ducts. It is postulated that smoking may have a direct toxic effect on the retro-areolar epithelial ducts (Versluijs-Ossewaarde et al. 2005). Central non-lactational breast abscesses have a high recurrence rate in 25–40 % of women with formation of cutaneous fistulas in a third of the women (Bharat et al. 2009; Lannin 2004). Microbiological analysis reveals mixed infection with staphylococcus, streptococcus and anaerobes (Benson 1989).

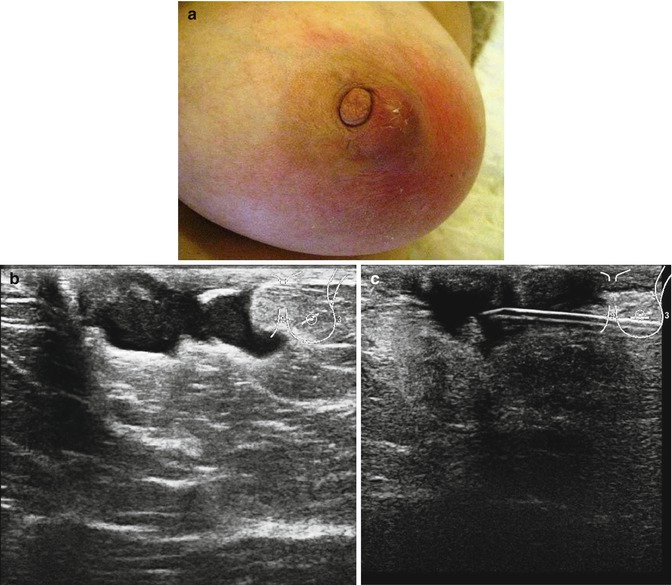

Fig. 6.1

(a) Central non-lactational abscess in a 52-year-old woman who presented with an abscess of the left breast. The skin is red and the abscess is ‘pointing’ as if it would burst at any time. (b) The ultrasound showed an irregular abscess. (c) The abscess was aspirated and reduced in size. The aspirated pus grew mixed flora and the patient was treated with Metronidazole. The abscess did not resolve and had to be excised

Peripheral non-lactational breast abscesses are less common than the central abscesses. They occur in older women with underlying chronic medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis (Trop et al. 2011). Other risk factors include steroid therapy, recent surgical intervention or post-radiation therapy. The most common pathogens are S. aureus and Streptococcus (Trop et al. 2011). Peripheral non-lactational abscesses respond well to drainage and antibiotics and recurrences are rare (Trop et al. 2011).

6.1.6 Radiological Features of Mastitis and Abscess

Since the conventional incision and drainage of abscesses is no longer recommended, patients with mastitis and breast abscesses are mostly managed by radiologists. Ultrasound is the first line of investigation because it is relatively painless, allows assessment of the breast during treatment and provides guidance for percutaneous drainage (Trop et al. 2011). On ultrasound imaging, mastitis appears as an ill-defined area of altered echo texture with increased echogenicity in the infiltrated and inflamed fat lobules, hypoechoic areas in the glandular parenchyma and associated mild skin thickening with occasional distended lymphatic vessels (Trop et al. 2011; Ulitzsch et al. 2004). The ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes may exhibit inflammatory features. The diagnosis of an abscess requires identification of hypoechoic collection of variable shape and size with multiloculation in the majority of the cases. There is often a thick echogenic periphery with increased vascularity. There is no vascularity in the collection but acoustic enhancement is present due to fluid content (Trop et al. 2011; Karstrup et al. 1993). The patient in Fig. 6.1a had ultrasound examination which confirmed an irregular abscess (Fig. 6.1b). The abscess was aspirated under ultrasound guidance. She did not undergo mammography.

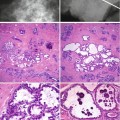

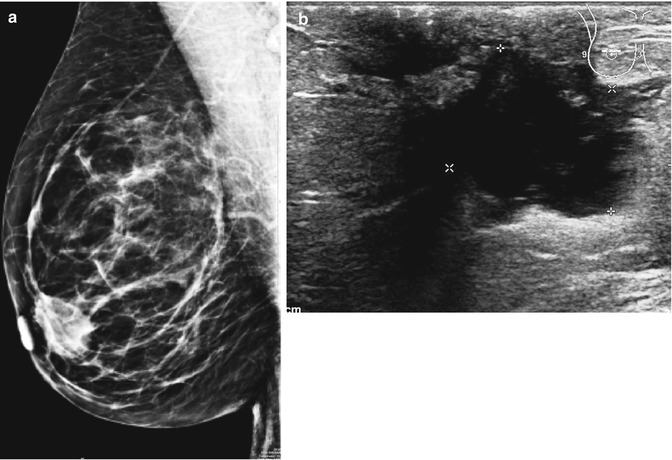

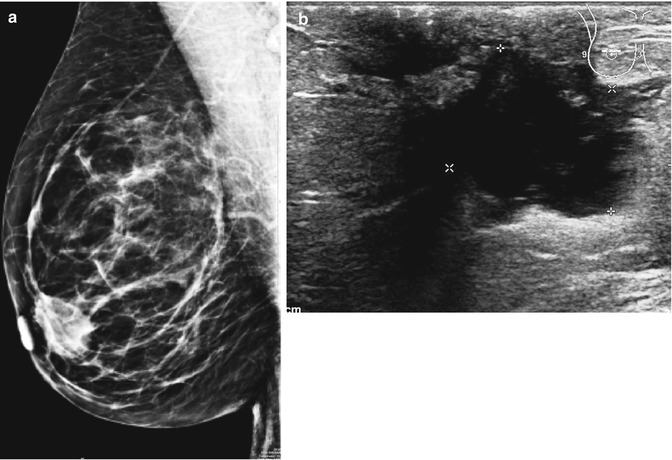

Mammography is recommended in women with breast abscesses outside the peripartum period, with some authorities advocating mammography in all women older than 30 years (Berna-Serna et al. 2004; Eryilmaz et al. 2005). However, mammography should be delayed until after the acute episode for the patient’s comfort. Mammography can show skin thickening, asymmetric density, a mass (Fig. 6.2a) or distortion which reflect the underlying inflammation and breast abscess. The ultrasound showed irregular shadowing suspicious of cancer (Fig. 6.2b). The main differential diagnosis of mastitis or abscess in an older non-lactating woman is an inflammatory carcinoma (Trop et al. 2011).

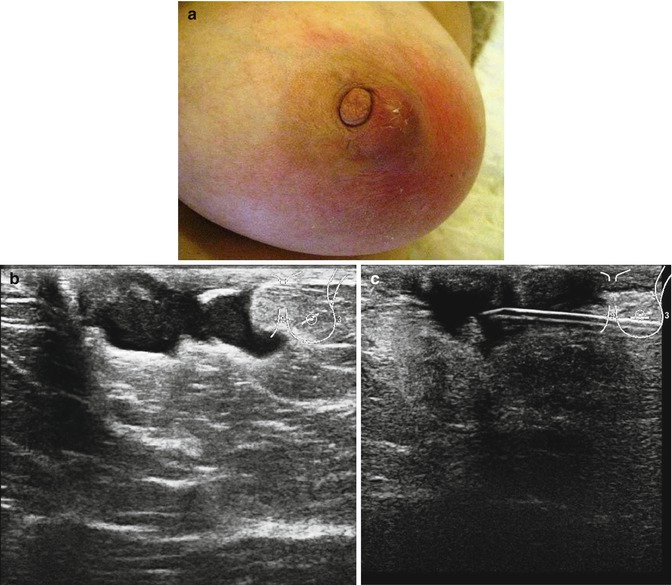

Fig. 6.2

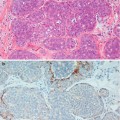

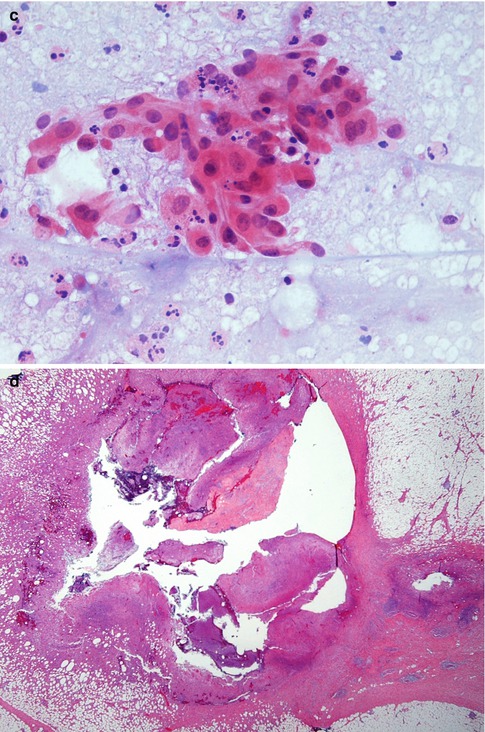

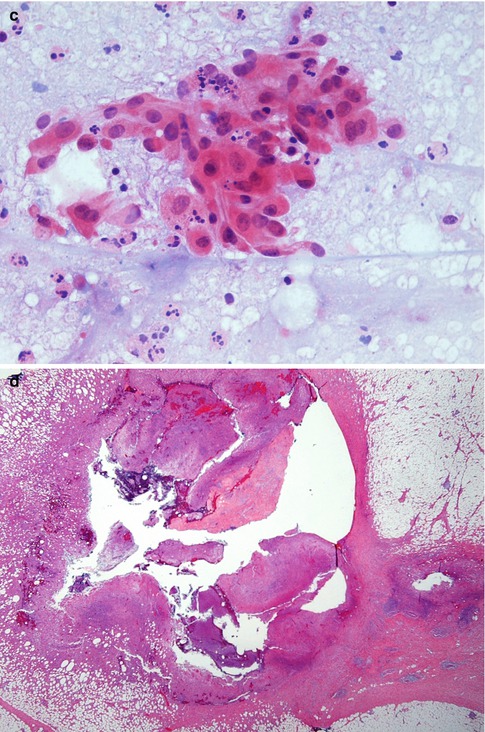

(a) Mammography in a 61-year-old woman shows subareolar mass. She presented with retracted nipple suspicious of cancer (R4). (b) The ultrasound showed an irregular shadow suspicious of cancer. (c) The aspirate contained pus cells and atypical cell suspicious of malignancy, H & E stain (C4). (d) The excision specimen showed an abscess cavity containing pus. The abscess is surrounded by a fibrous wall indicating chronicity. There is periductal mastitis in the surrounding tissue

6.1.7 Surgical Management of Breast Abscesses

Abscesses that fail to resolve after several attempts at percutaneous drainage are referred for surgery. Referral for surgery is indicated after several attempts (at least three to five) at ultrasound-guided drainage, although management decisions depend on the clinical context (Trop et al. 2011; Lannin 2004). Multiloculated and large abscesses (larger than 3 cm) are difficult to treat and are associated with an approximately 50 % rate of failure to cure with aspiration (Elagili et al. 2007; Schwarz and Shrestha 2001). Schwarz and Shreestha (2001) reported late presentation as a major factor associated with failure of percutaneous drainage in 33 women with breast abscesses, with a 100 % success rate reported in women treated within six of onset of symptoms.

Surgery is also indicated for recurrent central non-lactational abscesses. Lannin (2004) reported that medical nonsurgical management of recurring subareolar non-lactational abscesses was successful in 50 % in 67 of patients with the remainder requiring duct excision to control symptoms. In a separate study, Versluijs-Ossewaarde et al. (2005) reported that surgical excision of the inflamed ducts is not always curative in non-lactational abscesses with recurrence rate of 28 % (11 out of 39 patients).

6.1.8 Pathology of Breast Abscess

A breast abscess is like any other abscess occurring anywhere in the body. If aspirated the cytological material contains numerous polymorphs in the background of necrotic debris. Any epithelial cells sampled during the procedure will appear atypical due to inflammation and it may not be possible to exclude malignancy. The aspirate from the 62-year-old woman contained pus and atypical cells suspicious of malignancy (Fig. 6.2c), which lead to an excision biopsy.

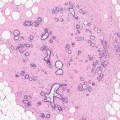

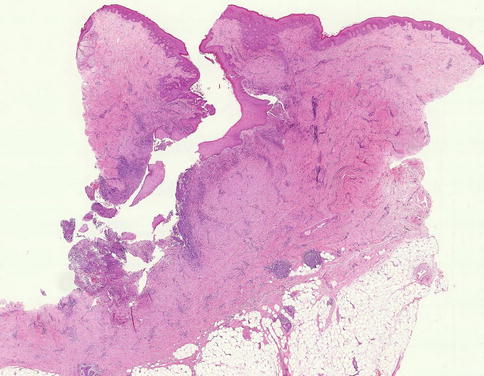

An excised abscess will consist of a central irregular cavity containing numerous polymorphs admixed with necrotic debris (Fig. 6.2d). The cavity is surrounded by necrotic tissue and walled off by fibrous tissue to indicate chronicity as the patient would have had prior conservative management (Fig. 6.2). If the inflammation does not resolve despite surgery and antibiotics, this may complicate into sinus tract (Fig. 6.3). This is a sinus excised from a different patient.

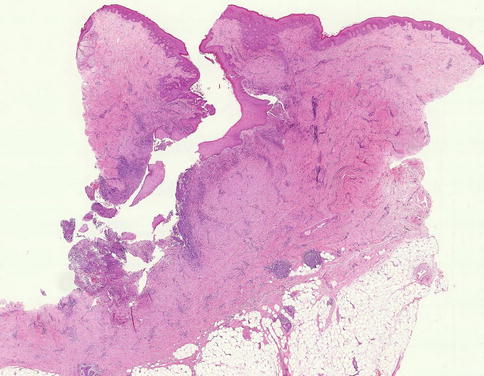

Fig. 6.3

A fistulous tract in a different patient, complicating a breast abscess

6.2 Duct Ectasia

6.2.1 Possible Aetiological Factors and Pathogenesis of Duct Ectasia

Haagensen (1951) applied the term mammary duct ectasia to a condition, which is characterised by dilated ducts and chronic inflammation. Duct ectasia had been known previously by other names such as ‘varicocele’ tumour (Bloodgood 1923), plasma cell mastitis (Adair 1933), comedo mastitis (Tice et al. 1948) and mastitis obliterans (Payne et al. 1943). These terms intended to portray the morphology as well as the possible aetiology of the disease process. Based on a clinico-pathological study of 20 women with duct ectasia, which clinically simulated carcinoma, Haagensen (1951) concluded that duct ectasia was an involutional condition that commenced with dilation of the nipple major ducts, followed by inflammation and fibrosis.

Duct ectasia usually coexists with periductal mastitis and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. There is no agreement among investigators regarding the pathogenesis of this condition. Multiple birth and lactation have been implicated as aetiological factors of the condition (Bonser et al. 1961). However, the role of pregnancy and lactation is not universally accepted as a possible aetiological factor in duct ectasia, as the condition also occurs in nulliparous women. Some authorities believe that stasis of luminal contents leads to duct ectasia and inflammation is a secondary process due to leakage of luminal contents (Tice et al. 1948; Haagensen 1951). In an earlier study, Foote and Stewart (1945) investigated the presence of periductal mastitis in cancerous and non-cancerous breasts. They observed that the most common histological feature of periductal mastitis was a predominant lymphocytic infiltrate around the mammary ducts. Although they did not apply the term duct ectasia, they noted that the appearances of the inflammatory cells were nearly in every case preceded by other changes, such as stasis of amorphous acellular and cellular duct contents, dilation of the duct wall and varying degrees of atrophy of periductal myoid tissue. It is not clear from this paper how the authors came to the conclusion that the duct dilation preceded the inflammatory process.

When Dixon et al. (1983) reviewed 88 biopsies from patients with duct ectasia, they noted that biopsies from younger women showed severe periductal inflammation around non-dilated ducts and the patients had presented with mastalgia or a symptomatic lump. In contrast, biopsies from older patients showed duct dilation as the main pathological feature and these patients had presented with nipple retraction. Based on these observations, Dixon and colleagues postulated that the sequence of events is more likely to be periductal inflammation followed by resolution of the inflammatory process, leading to periductal fibrosis and duct dilation. These pathological features can be correlated with the clinical presentation: thus breast pain and lump in the younger women, which pathologically is consistent with periductal inflammation, and nipple retraction in the older women due to resolution of inflammation is associated with fibrosis and dilation of ducts. The authors felt that the term duct ectasia described the outcome of the inflammatory process but not the primary lesion and suggested that the appropriate term should be periductal mastitis.

Previously Bonser et al. (1961) reached a similar conclusion to Dixon et al. (1983) as the inflammatory process was more prevalent in younger than older women. However, Dixon could not confirm the association of duct ectasia with parity and lactation. Anaerobic organisms have been isolated in some patients with duct ectasia and some patients benefit from antibiotic therapy (Dixon 1989). Most studies reported sterile secretions, including lack of mycobacterial infection. The process of periductal mastitis/duct ectasia progresses to duct fibrosis with obliteration of ductal lumina and this was termed mastitis obliterans (Payne et al. 1943). Granulomatous inflammation with giant cells is not uncommon in duct ectasia. Trop et al. (2011) advocates a squamous metaplasia of the cuboidal epithelium of the lactiferous ducts as the initiating factor which leads to formation of keratin plugs followed by acute inflammation, obstruction of ducts leading to dilatation. Stagnation predisposes to secondary inflammation.

Smoking has also been implicated as an aetiological factor in duct ectasia and this appears to be due to the direct toxic effects on the breast epithelium (Furlong et al. 1994). Younger women who smoked more than ten cigarettes a day had more periductal inflammation than those who did not smoke. Duct ectasia was more prevalent in older than younger women. In a later study, Dixon et al. (1996) also confirmed that periductal mastitis was more prevalent in young women who smoked, whereas duct ectasia tended to affect older women who did not smoke. The earlier suggestion that periductal mastitis preceded duct ectasia (Dixon et al. 1983) was contradicted in the 1996 publication by the same authors who suggested periductal mastitis and duct ectasia should be regarded as two different conditions affecting different age groups due to different aetiological factors. Despite the conflicting reports on the possible pathogenesis of periductal mastitis/duct ectasia, and whether they are two different diseases or the same disease process, in routine surgical pathology, periductal mastitis and duct ectasia are invariably present in the same breast biopsy or histological slide suggesting a continuum of the same disease process, without resorting to the dilemma of which came first.

6.2.2 Clinical Features of Duct Ectasia

Duct ectasia can be unilateral or bilateral. Although the condition is prevalent in women, it can also occur in men (Al-Masad 2001). In the early stages the women present with nipple discharge. The discharge can be off-white, creamy, brown, grey or green and can be thick as toothpaste (Mansel et al. 2009). Bloodstained nipple is less common but duct ectasia causes bloodstained nipple discharge more so than duct papilloma. Patients who present with nipple discharge tend to be perimenopausal or postmenopausal. Mansel et al. (2009) describes four types of masses associated with duct ectasia:

(a)

The evanescent mass which is a small, slightly tender subareolar lesion which appears and resolves spontaneously, usually without treatment.

(b)

The recurrent mass which represents the evanescent mass occurring in the subareolar region at intervals of a few months to 10 years. The condition has a tendency to become more severe with each recurrence and can be bilateral.

(c)

The persistent mass which is present for some weeks is usually firm and well-defined. Fine needle aspiration cytology shows foamy macrophages and inflammatory cells. As cancer cannot be excluded, an excisional biopsy is usually warranted.

(d)

The chronic mass which is hard, oedematous and fixed to the skin with associated nipple retraction and has all the hallmarks of cancer, especially if associated with axillary lymphadenopathy. A formal excision biopsy with antibiotic cover is advocated.

Other clinical presentations or complications of duct ectasia are breast abscess and mammary duct fistula. The fistula can be due to an abscess discharging spontaneously or a complication of surgical drainage of the abscess. This is associated with scarring of the areola and nipple inversion. Mansel et al. (2009) emphasises the need for caution when advising women about duct excision.

The clinical features of duct ectasia invariably mimic carcinoma. Screening mammography now frequently detects carcinoma in the background of calcified duct ectasia. This is a coincidental finding in older women rather than a causal relationship.

In Haagensen’s (1951) series of patients with duct ectasia, the average age was 55.4 years. This would support the theory that duct ectasia is the end product of periductal mastitis, although Haagensen believed that duct ectasia preceded mastitis. Foote and Stewart (1945) reported ductal stasis and distension to be more prevalent in women over 50 years, but there was no difference in the presence of these lesions in cancerous and non-cancerous breasts.

There are no reports to date indicating that periductal mastitis or duct ectasia is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Bonser and colleagues (1961) reported 82 cases of duct ectasia in association with 220 specimens containing breast cancer. In 14 patients, the cancer was arising in ectatic ducts; in 30 patients, cancer was present in the same segment as duct ectasia but outside the ducts, and in 38 patients, cancer was in the segment without duct ectasia. This association was considered coincidental rather than causal. The investigators asserted that if duct ectasia were premalignant, there would be a high prevalence of cancers arising in dilated ducts in women over 50 years of age. The low prevalence of cancer arising in duct ectasia is most likely due to the fact that in periductal mastitis/duct ectasia there is destruction rather than hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium. However, some ducts exhibit squamous metaplasia and this raises the possibility of whether this metaplastic epithelium may predispose to primary squamous cell carcinoma of the breast.

Despite the characteristic pattern of calcification in duct ectasia, there are occasions in which duct ectasia mammographically mimics carcinoma and this requires diagnostic biopsy to exclude malignancy. Sweeney and Wylie (1995) reported 12 cases of duct ectasia that were mammographically suspicious of carcinoma. Eight cases showed clusters of microcalcification, three spiculated masses and three lobulated masses. These cases required fine needle aspiration cytology and biopsies to exclude malignancy. Duct ectasia simulating carcinoma previously led to mastectomies in a period when preoperative biopsies and multidisciplinary team meetings were not routine (Adair 1933; Haagensen 1951).

6.2.3 Radiological Features of Duct Ectasia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree