INTEGRATING IMAGING AND PATHOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS

KEY POINTS

- Imaging findings must be correlated with clinical context and pathologic findings to ensure optimal medical decision making.

- When imaging and pathologic interpretations are disparate, both must be reconsidered in light of the clinical issues and each other.

- One must be very careful when a clinical decision is based on imaging morphology of a lesion not confirmed by biopsy—there are almost always two things in the differential.

The head and neck is divided into various, generally accepted “regions” such as craniofacial and neck. Many of the pathologic processes discussed in each region occur in several of the others, the main differences being frequency of involvement, some morphologic variations, and those related to displacement or distortion of surrounding anatomy. There are, however, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) features that are the same regardless of the site. Moreover, the histopathologic classification and basic natural history of a specific pathologic process usually varies little at different sites. Since these unifying themes exist, the concepts listed below will be presented here and in the following pathologically rather than anatomically oriented discussions (Chapters 8–43). The aim of this approach, as outlined in the five items that follow, is to reduce some redundancy in the more site/region specific chapters (Chapters 44 through 226) that follow.

(1) General morphology and classification of infectious and noninfectious inflammatory disorders

(2) General classification, morphology, and histopathologic features of benign and malignant neoplasms and congenital lesions

(3) Basic spread patterns of inflammatory and neoplastic pathology

(4) Limitations in the differentiation of neoplasm, inflammation, reactive changes, and posttreatment findings on imaging studies

(5) Relative roles of imaging and needle biopsy, including the role of imaging-directed biopsy

This pathologically oriented presentation deals largely with the natural history of head and neck pathology as it is seen in studies predominantly on CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and, when appropriate, ultrasound, radionuclide studies, angiography, and plain films. Remember that these imaging studies sample pathology that is usually evolving.

The reader should constantly refer back to this section, as suggested in the anatomically and clinically based discussions that follow, in order to gain a comprehensive picture of the pathologic process being studied. Understanding of the natural history of a disease process as well as the clinical importance of the imaging findings in a given patient may lead to improved patient care.

The anatomic and clinically based discussions in this chapter will utilize the basic trends described in this pathoanatomic and pathophysiologic treatment of disease states and refine them as they apply to the respective head and neck regions. Those site-specific discussions will include more specific clinical issues that affect patient management.

THE BASIC TASKS

Diagnostic imagers are expected to do four basic tasks: (a) detect pathology by determining what is abnormal versus normal, (b) help determine the most likely diagnosis, (c) delineate the extent of disease, and (d) verify the progress of therapy. These jobs are best done in the context of a cooperative effort of an interdisciplinary treatment team. This implies that all relevant clinical and pathologic data will be available when planning and interpreting the study. As a corollary, the clinical and pathologic data such as that from the physical examination and endoscopy should always be interpreted in light of imaging findings. Any good bone pathologist requires that imaging studies of a bone tumor be available when interpreting the histopathology. The same demand exists in many cases of pathology involving the head and neck. In this way, imaging becomes another piece of the puzzle and in difficult cases may be pivotal for arriving at the correct diagnosis (Fig. 7.1).

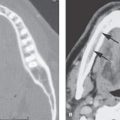

FIGURE 7.1. Patient had a neck biopsy before imaging at another institution and was believed to have squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes. Neck dissection was planned following endoscopy that failed to reveal a primary tumor. This contrast-enhanced computed tomography study shows the tumor (Tum) to lie within the paravertebral compartment deep to the deep layer of cervical fascia, so it cannot be an abnormal lymph node, as nodes would be in the fatty envelope of the anterior or posterior triangle (arrow). Sarcoma was suspect from this image and confirmed by re-evaluation of the original biopsy material. Management was significantly changed by these imaging findings.

In other situations, imaging provides information that is unavailable by standard clinical examination (Fig. 7.2). MR and CT routinely show disease extending beyond that demonstrated by physical examination (Fig. 7.3). This data often results in changes in management (Fig. 7.4).

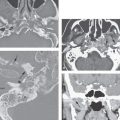

FIGURE 7.2. Images of a patient presenting with progressive dysphagia localized to the lower neck region. Endoscopy showed no mucosal lesion, and endoscopic biopsy guided by these magnetic resonance (MR) findings of an obvious submucosal cervical esophageal tumor (Tum) did not confirm cancer. A: Non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image. B: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image. C: T2-weighted MR image. D: D: Percutaneous CT-guided biopsy returned squamous cell carcinoma. MR and CT routinely show disease extending beyond that demonstrated by physical examination.

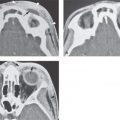

FIGURE 7.3. Tonsillar cancer believed clinically to be confined to the tonsil. A: Cancer (Tum) involves the posterior pharyngeal wall and palatine tonsil more on the left side. B: A very large, necrotic retropharyngeal lymph node (RPN) was not appreciated on physical examination. C, D: The node (RPN) extends to the skull base along the carotid artery (arrow), making surgery a nonviable option for this patient.

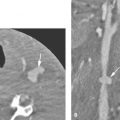

FIGURE 7.4. Patient was sent from an outside hospital for a biopsy of a parapharyngeal mass for a biopsy. A, B: Computed tomographic angiography images that show the mass to be a distal cervical internal carotid aneurysm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree