INTRACONAL ORBIT: TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are in the critical pathway for evaluating the signs and/or symptoms that are related to an intraconal-origin orbital neoplasm.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are extremely useful for narrowing the differential diagnosis of disease that may arise in the muscle cone but have limits in differentiating benign tumors or low-grade malignant tumors from cavernous vascular malformations.

- Imaging with magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography will help establish whether the disease process is localized or possibly systemically related.

- If a lesion is not to be biopsied or removed, magnetic resonance and computed tomography should be used to establish whether its rate of growth is consistent with a benign or malignant process.

Any orbital mass or disease process may be approached by first establishing whether it is preseptal (Chapters 70 and 71) or postseptal (Chapters 57–60, 62, and 64). If postseptal, it should be established as a process arising primarily intraconally (Chapters 57–60), extraconally (Chapters 62 and 64), or transcompartmentally. If intraconal, it should be decided whether the mass is of optic nerve/sheath origin or arises from some other structure comprising or within the muscle cone. This chapter considers intraconal tumors and those arising intraconally and not of optic nerve/sheath origin as well as those arising intraconally and spreading across the orbital compartments and related spaces.

The epicenter of these lesions should be clearly within the rectus muscles group or their confines behind the eye whether the tumor is well circumscribed or infiltrative. The mass should be considered of origin in this space only if it is very likely not of the optic nerve/sheath. This point is important since exophytic lesions of the optic nerve sheath occur, and a major determinant in the differential diagnosis is whether the lesion secondarily displaces or arises from the optic nerve/sheath complex.

Benign tumors arising in the central surgical space or from the four rectus extraocular muscles are extremely uncommon. Benign neurogenic tumors (Chapters 29 and 30) of the orbit arising in the muscle cone are rare. Isolated schwannomas and neurofibromas may involve peripheral branches of orbital nerves and mimic more common orbital masses such as a cavernous vascular malformation; the final diagnosis is usually a surprise. More often, neurogenic orbital tumors are a manifestation of neurofibromatosis.1,2 In neurofibromatosis, the tumors often extend from the trigeminal ganglion along the peripheral course of one or more of the divisions of the trigeminal nerve and only appear to be intraconal or only have a minor intraconal component.

Other benign tumors are even rarer, such as a meningioma arising from ectopic arachnoid cells separate from the optic sheath within the central surgical space and mesenchymal tumors of fibrous origin.

Malignant intraconal tumors are likely to be rhabdomyosarcoma in a child and lymphoma or metastatic disease in an adult. Other primary intraconal malignancies are rare and include hemangiopericytoma and melanoma.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

The relevant anatomy of the orbit, eye, and optic nerve/sheath complex is discussed in detail in Chapter 44. In particular, the anatomy of the rectus muscles and structures within the muscle cone should be reviewed.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The orbit, eye, and optic nerve and sheath are studied with ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance (MR) techniques described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45. Specific CT protocols by indications are detailed in Appendix A. Specific MR protocols by indications are outlined in Appendix B. Almost all studies to investigate intraconal pathology are done with contrast.

Pros and Cons

Disease of and within the muscle cone is studied primarily with CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is far more definitive in its rendering of the optic nerve and ocular effects of such disease and providing objective evidence of secondary optic nerve compromise. MRI is likely to be more sensitive than CT to possibly related intracranial abnormalities associated with these tumors.

CT may also be done first for an emergent evaluation of possible associated tension orbit. It is also a first choice in patients too sick or for some other reason unable to complete a very high quality, free of motion artifact, MRI examination. CT is a reasonable secondary screening tool for identifying intracranial extension of disease and intracranial complications.

The use of US is for the most part restricted to the identification of a swollen optic disc and possible intraocular complications of disease primarily within the muscle cone. US may show findings immediately adjacent to the nerve–globe junction and around the distal sheath that marginally contribute to the differential diagnosis.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Benign Tumors

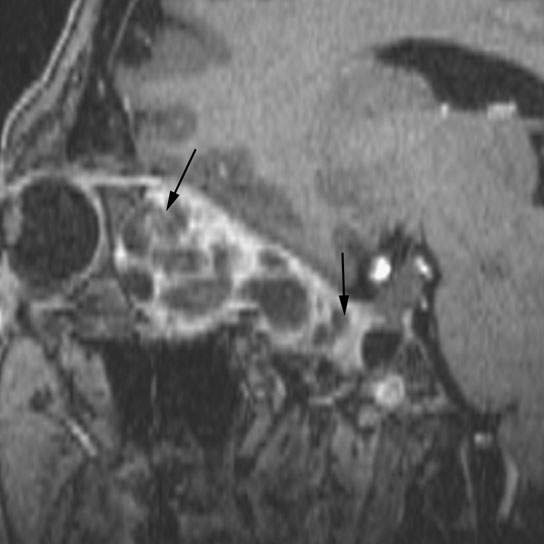

Benign intraconal lesions are rare. Neurogenic tumors (Chapter 30) arise from small nerves in the muscle cone (Figs. 29.9 and 60.1). Rests of arachnoid cells may give rise to a meningioma (Chapter 31) that is separate from the optic sheath. Benign fibrous origin neoplasms (Chapter 37) also occur (Figs. 37.17, 37.19, and 60.2).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These lesions are spontaneous occurrences in children and adults. Neurogenic tumors associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 do not typically arise within the muscle cone (Fig. 29.9A).

Clinical Presentation

These benign tumors may present with painless proptosis. There may eventually be visual loss, diplopia, and/or other manifestations of ocular dysmotility.

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

These benign tumors are almost all firm; thus, proptosis is often the presenting feature. Involvement at the orbital apex may herald a compressive optic neuropathy and possible early intracranial spread through the superior orbital fissure, as might occur earlier with more posteriorly arising tumors (Figs. 29.9B–F and 60.1).

Otherwise, these tumors grow in a fashion typical of benign tumors as described in Chapter 21.

FIGURE 60.1. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat-suppressed sagittal image shows a schwannoma arising in the muscle cone and extending to the orbital apex (arrows). Other images on this same case can be seen in Figure 29.9.

Manifestations and Findings

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The CT and MRI appearance of neurogenic tumors (Chapters 29 and 30), meningiomas (Chapter 31), and the rare benign fibrous tumors and mesenchymal[SF2] (Chapter 35 and 37) that arise from the muscle cone are discussed in the chapters indicated. Neither MRI nor CT will typically show any unique features. CT will show their effects on bone if a tumor extends beyond the muscle cone or to the orbital apex and optic canal (Figs. 29.9B–F and 60.1). Both MRI and CT will show the general relationship to the mass and optic nerve/sheath complex. MR may demonstrate optic nerve compromise more clearly than CT, but in larger lesions this may prove difficult (Figs. 37.17, 37.19, and 60.2).

MR may show signal intensity equal to or lesser than muscle on T2-weighted images if the tumor has a significant muscle or fibrous component.3 It will also reveal early intracranial spread if the tumor extends beyond the muscle cone to the orbital apex and optic canal.

Differential Diagnosis

From Clinical Data

Proptosis is related to both the size and firmness of the lesion. These benign tumors are almost all firm; thus, proptosis is often the presenting feature. Compressibility of the lesion or overall orbital contents and/or changes with position or Valsalva favors a vascular malformation. Rapid enlargement favors a malignancy, complication of a vascular malformation, or possible inflammatory lesion. Vascular congestion typically suggests a tumor other than benign intraconal mass. Pain suggests pseudotumor or malignancy or an inflammatory lesion.

From Supportive Diagnostic Techniques

Diagnostic imaging provides the best means of diagnosis short of biopsy. In general, imaging will separate benign from likely malignant tumors based on the growth pattern and recognition of associated findings such as multiple lesions. Imaging may not differentiate low-grade malignancies from benign tumors or even well-encapsulated cavernous malformations. Watchful waiting with imaging surveillance or removal in worrisome lesions is often employed to arrive at a reasonable assessment of what the lesion might be.

Medical Decision Making and Treatment Options

Medical

These tumors are sometimes observed.

Surgical

If confined to the muscle cone and separate from the optic nerve/sheath complex, these lesions can be excised without producing a deficit in visual function. The specific surgical approach will depend on its position in the muscle cone as defined on MR and/or CT.

Surveillance Options

MR is typically used to follow up on tumors believed to be benign or those that cannot be differentiated with certainty from encapsulated cavernous malformations.

DISEASE ACUITY AND REPORTING RESPONSIBILITY

Unless there is a threat of compressive optic neuropathy or aggressive behavior that suggests a malignant tumor, reporting can be routine.

The report should clearly establish the position of the tumor relative to the optic nerve/sheath complex establishing both whether or not it is separate from that structure and in which quadrant the mass lies relative to the muscle cone. It must also establish its extent relative to the optic canal and superior orbital fissure and exclude intracranial involvement.

As much as possible, the report must distinguish a cavernous vascular malformation from a potentially malignant tumor since a malformation is typically not removed or biopsied if it is asymptomatic.

The report must emphasize, at the time of first discovery, that even though the mass appears benign, a rare primary or metastatic malignant tumor can appear identical to a benign tumor and serial studies must be done to confirm a benign rate of progression if observation is the chosen form of management rather than removal. This is true even if the lesion is thought to represent a vascular malformation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree