Ischiofemoral impingement syndrome (IFI) is a source of extra-articular pain caused by narrowing between ischium and femur in native hips. Secondary compression of quadratus femoris muscle leads to edema, tears, and deep gluteal pain. IFI is more frequent in females, with evidence pointing to a combination of hip, spine, and pelvic biomechanics and morphology leading to abnormal osseous relationships. This article provides updated concepts regarding the diagnosis, biomechanics, imaging, and treatment strategies for IFI. Moreover, IFI is emphasized as a multifactorial native hip syndrome, in contrast to ischiofemoral narrowing from secondary causes such as surgery, trauma, or masses.

Key points

- •

Ischiofemoral impingement syndrome (IFI) is an extra-articular compression phenomenon caused by narrowing between ischium and proximal femur in native hips.

- •

Most common in females; IFI presents with deep gluteal pain and occasional sciatica, being associated with secondary quadratus femoris muscle edema and tears.

- •

Diagnosis of IFI requires a combination of clinical symptoms, positive physical examination tests, and imaging findings.

- •

Pelvic and femoral morphology contribute to IFI, and imaging protocols should consider hip biomechanics to accurately show ischiofemoral narrowing.

- •

Treatment strategies include palliative injections for pain and decompressive surgery.

Introduction

Ischiofemoral impingement syndrome (IFI) was first described in 2009 by Torriani and colleagues as an abnormality characterized by hip pain, ischiofemoral space narrowing, and quadratus femoris muscle abnormalities. Fifteen years later, a growing body of research has provided insights regarding biomechanics, pelvic and femoral morphology, with implications in imaging protocols, diagnostic criteria, and treatment. This review discusses current concepts that advanced the understanding of IFI and may serve to inform future management and research.

Background and terminology

Since its introduction, the term “ ischiofemoral impingement syndrome” has been broadly used to describe ischiofemoral (IF) space narrowing in 2 main situations as follows:

- a.

in native (non-surgical) hips; and

- b.

secondary to surgery, trauma, or local masses.

It is increasingly clear these represent distinctive settings. Current evidence suggests IF narrowing in native hips has a multifactorial etiology involving lumbar spine alignment, hip abductor muscle status, , pelvic configuration, , and hip and femoral morphology. , This is in contrast to IF narrowing from surgical changes, post-traumatic deformities, or masses (eg, enchondromas, soft tissue tumors). , This distinction emphasizes that caring for IFI patients requires consideration of its multifaceted origin, while IF narrowing from secondary sources can be resolved with direct measures (eg, excision of a mass). In this review, ischiofemoral impingement syndrome (abbreviated as IFI) will refer exclusively to “primary” IF space narrowing in native hips, without prior surgery, trauma, or masses.

Clinical presentation

The diagnosis of IFI requires a combination of clinical and imaging findings. Briefly, the syndrome is defined as hip pain with IF space narrowing, commonly associated with quadratus femoris (QF) muscle abnormalities, such as edema, tears, or chronic atrophy. , , Most series in the literature show IFI is more common in adult females, , , , , , although it has also been described in children. Importantly, IF and QF spaces are often asymmetric in asymptomatic subjects, who may also have abnormal QF muscles. Therefore, radiologists are cautioned to avoid diagnosing IFI by imaging alone and should consider clinical symptoms and positive provocative tests.

The clinical presentation of IFI can be bilateral in 25% to 40% of cases. Usual symptoms include deep gluteal pain, sciatica, and snapping. , Limited sitting time and restricted long-stride walking are frequent, with a common antalgic position of sitting on unaffected ischium. Physical examination is enhanced by 2 provocative tests, with high accuracy for IFI .

- a.

The IFI test in lateral decubitus (0.82, sensitivity—0.85, specificity), in which passive hip extension and adduction cause impingement symptoms ; and

- b.

Long-stride walking test (0.94—0.85), which causes impingement of lesser trochanter on ischium during active hip extension, producing pain lateral to ischium during terminal extension, relieved by shortening stride length.

Imaging findings

At initial presentation, radiographs are commonly obtained. However, they are limited due to their planar nature, which may only reveal IF space narrowing in severe and chronic cases. However, in a prior study, supine and standing radiographs had good ability to discriminate between IFI versus controls, with excellent interobserver agreement. Altogether, radiographs may be a useful initial step to rule out other hip abnormalities, such as osteoarthritis, post-traumatic deformities, and prior surgery.

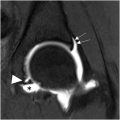

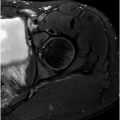

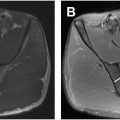

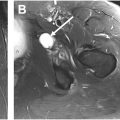

Cross-sectional imaging is critical in establishing IFI and associated soft tissue changes. At first, evaluation is often qualitative. Quantitative assessment may help increase diagnostic confidence ( Fig. 1 ), with caveats related to hip positioning (please see Measurements and Measurement Pitfalls below). Overall, MR imaging is the preferred imaging method, as it is best suited to characterize QF muscle abnormalities, which can range from mild edema to partial or full-thickness tears , ( Fig. 2 ). Chronically, the QF muscle may show varied degrees of atrophy and fatty infiltration ( Fig. 3 ). Edematous changes in surrounding soft tissues and potentially contacting the sciatic nerve are well demonstrated with MR imaging and can explain referred symptoms such as sciatica and lower extremity pain , ( Fig. 4 ). Hamstring origin abnormalities are often present and include degenerative high signal intensity and partial tears, as well as increased cross-sectional area. Osseous changes may include marrow edema, and in chronic cases, subcortical cysts may be present ( Fig. 5 ).

Although computed tomography (CT) provides excellent osseous detail for bilateral appraisal of IF space ( Fig. 6 ), it lacks detail for soft tissue abnormalities. Sonography is able to measure the IF space dynamically, however, may be limited to demonstrate the QF muscle in detail, especially in larger patients.

Measurements

Quantitative parameters in IFI derive mostly from MR imaging-based case-control studies. Two valuable measurements are preferably obtained from axial images , (see Fig. 1 ).

- •

IF space: smallest distance between lateral ischium and medial lesser trochanter cortex;

- •

QF space: smallest distance between lateral surface of hamstrings and medial lesser trochanter cortex.

As discussed in Measurement Pitfalls (below), the degree of hip rotation and flexion during MR imaging can substantially influence these measures. Further, although most IFI literature has focused on (osseous) IF space narrowing, the QF space should also be evaluated. Functionally, a lateralized and expanded hamstring origin may be a source of QF muscle compression against the lesser trochanter, especially with the hip in external rotation and extension.

From a practical standpoint, a meta-analysis examining 27 studies examining subjects with IFI provides thresholds that are useful to determine space narrowing on routine hip MR imaging .

- •

IF space ≤ 15 mm: 77% sensitivity—81% specificity—78% overall accuracy

- •

QF space ≤ 10 mm: 78% sensitivity—74% specificity—77% overall accuracy

Additional measurements of hip and pelvis morphology on static MR imaging have been examined in IFI, including, among others, femoral inclination angle, intertuberous distance, , and ischial and femoral neck angles. Although these parameters have provided better understanding of morphologic factors in IFI, they may not be easily obtained on routine MR imaging if anatomic coverage is limited.

Importantly, due to the variability introduced by hip positioning, measurements should not be the only parameter for diagnosis of IFI. As previously discussed, clinical tests and history play a key role in the diagnosis and imaging should be supportive of a comprehensive evaluation.

Measurement pitfalls

Early IFI publications relied on retrospective series and static MR imaging protocols using neutral or internal rotation to ensure consistent hip positioning. , , , However, recent studies have shown dramatic changes to IF space based on hip rotation or flexion. Narrowing between ischium and lesser trochanter is most pronounced at hip external rotation , ( Fig. 7 ). External rotation may also reveal narrowing between ischium and greater trochanter, with the potential to produce similar symptoms and compression of QF muscle.

Hip flexion, prone or supine position, can also significantly affect IF space measures. The IF space can range from 1.4 cm at 60° hip external rotation to 4.3 cm at 40° internal rotation, , and combined rotation and flexion can substantially influence the spaces. , Importantly, routine MR imaging and CT only provide static information of a highly dynamic joint with wide range of motion. In a study using dual fluoroscopy and 3-dimensional hip reconstructions of asymptomatic hips, the minimum IF space during dynamic activities (incline and level walking) was significantly lower than observed on axial MR imaging. The authors concluded that IF space measured from static images did not accurately represent the minimum values, requiring greater hip extension, adduction, and external rotation to reflect dynamic changes. Further, in a recent in vivo dynamic study, IFI patients showed narrowing that remained unchanged between normal and long-stride walking.

These findings were extended by a kinematic MR imaging study, showing that at maximal hip external rotation in normal hips, the lesser trochanter moves medially toward the ischium in a U-shaped arc, avoiding bone contact at the terminal position. In hips with IFI, external rotation causes the lesser trochanter to drift medially along a flattened arc, terminating closer to the ischium. Therefore, awareness of hip positioning during imaging is critical to correctly interpret IFI measurements. Altogether, current data suggest routine static MR imaging protocols with hips in neutral or internal rotation likely overestimate the minimum IF space, underscoring the importance of clinical tests for IFI.

In the author’s experience, 2 common situations are present when IFI is suspected on routine hip MR imaging.

- •

Narrowed IF space and abnormal QF muscle: this is the most recognizable presentation of IFI (see Figs. 2–7 ), which should be correlated to clinical tests, symptoms, and history for comprehensive diagnosis and management.

- •

Normal IF space and abnormal QF muscle ( Fig. 8 ) : considerations should include the following:

- ○

QF muscle strain or tear, which can occur from physical activities such as tennis, badminton, lifting, and orienteering.

- ○

IFI is present; however, IF space narrowing is not visible due to hip positioning that widened the space (eg, internal rotation, flexion). In the absence of visible narrowing, clinical tests and history should guide the differential diagnosis. As described in Imaging Recommendations (below), dedicated imaging with hips in internal versus external rotation may be helpful, and scans with hips in neutral versus maximal extension may correlate to long-stride walking test.

- ○

IFI is present; however, IF space narrowing and QF muscle compression are occurring more proximally, between greater trochanter (or intertrochanteric ridge) and ischium. , MR imaging with hip in flexion-abduction-external rotation (FABER) position may be helpful for evaluation.

- ○