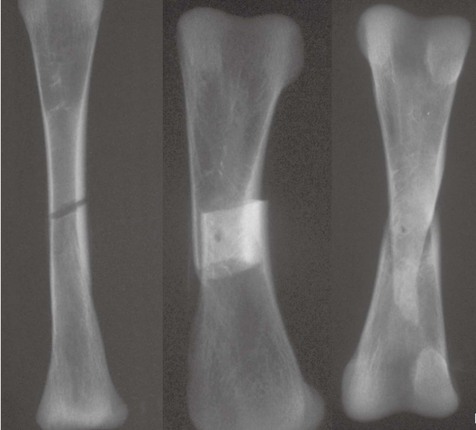

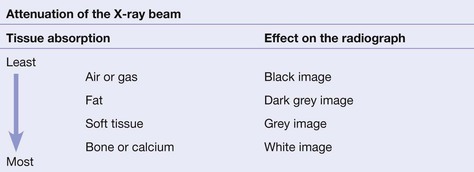

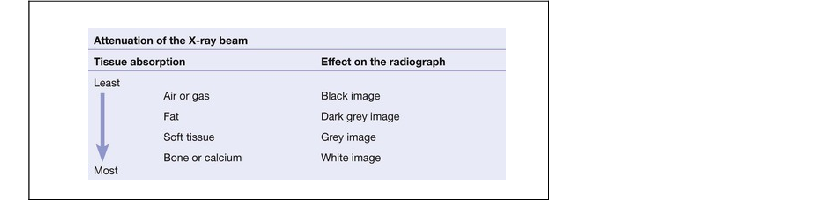

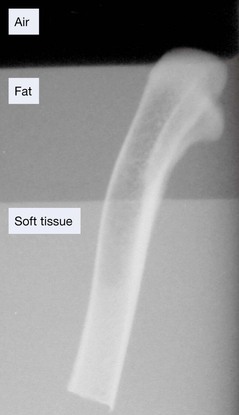

Introduction Patients with traumatic injuries can be placed into one of three major groups. The imaging approach will differ between these groups. The tissues that lie in the path of the X-ray beam absorb (ie attenuate) X-rays to differing degrees. These differences account for the radiographic image. Radiograph of a chicken leg (bone) partially submerged in a layer of vegetable oil (fat) floating on water (soft tissue). Note the difference in the blackening of the X-ray film due to absorption by the different tissues. When a fracture results in separation of bone fragments, the X-ray beam that passes through the gap is not absorbed by bone. This results in a black (ie lucent) line on the radiograph. On the other hand, bone fragments may overlap or impact into each other. The resultant increased thickness of bone absorbs more of the X-ray beam and so results in a white (ie sclerotic or denser) area on the radiograph. There are radiological soft tissue signs which can provide a clue that a fracture is likely. These include displacement of the elbow fat pads (see pp. 97 and 102), or the presence of a fat–fluid level at the knee joint (see pp. 248–249). ‘One view only is one view too few’ Many fractures and dislocations are not detectable on a single view. Consequently, it is normal practice to obtain two standard projections, usually at right angles to each other. The example below shows two views of an injured finger. At sites where fractures are known to be exceptionally difficult to detect (for example a suspected scaphoid fracture), it is routine practice to obtain more than two views. Knowledge of the patient’s position during radiography is essential. A radiograph obtained with the patient lying supine may produce a very different appearance when compared with the image acquired with the patient erect.

Key principles

Basic radiology

The radiographic image

Fracture lines: usually black, but sometimes white

Fat pads and fluid levels

The principle of two views

Important information: patient position

Related posts:

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree