LABYRINTHITIS

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography are commonly performed to look for abnormalities of the labyrinth, cochleovestibular nerve, or cerebellopontine angle.

- Pathology in this region may be diverse, as discussed in this chapter and in Chapters 134 and 135, but in the majority of cases is a straightforward diagnostic situation.

- Imaging can be very helpful to triage patients with labyrinthine dysfunction to the next best step in the medical decision-making process.

INTRODUCTION

Etiology

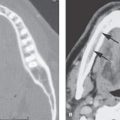

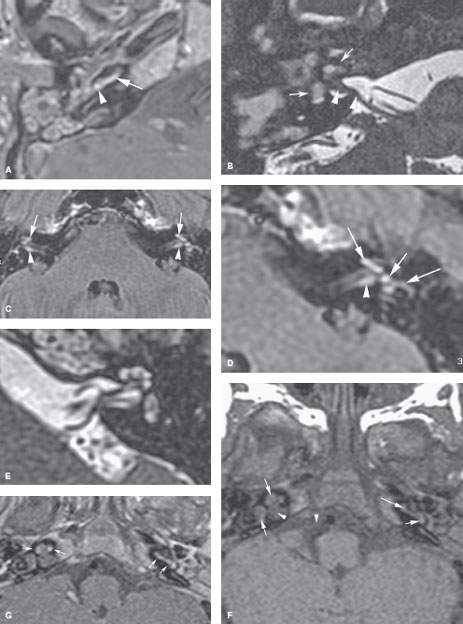

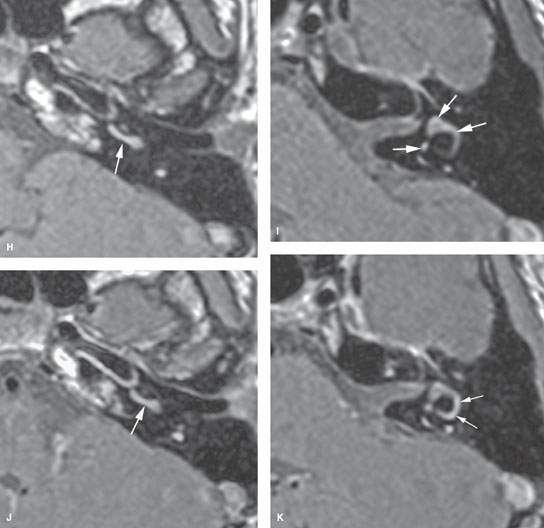

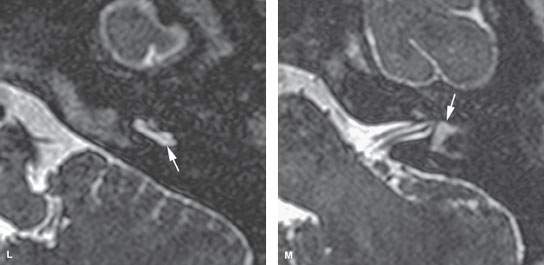

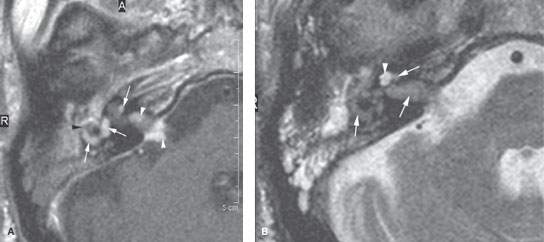

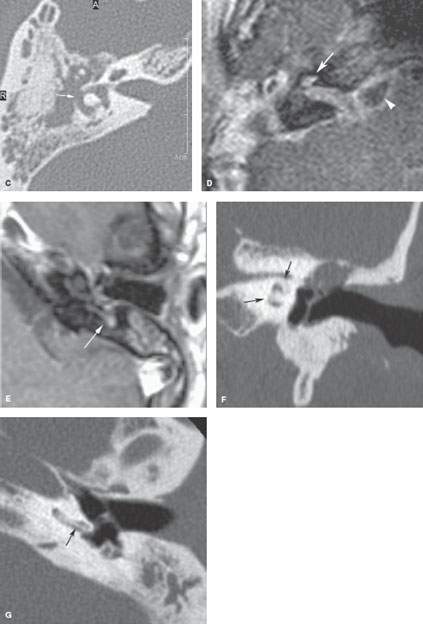

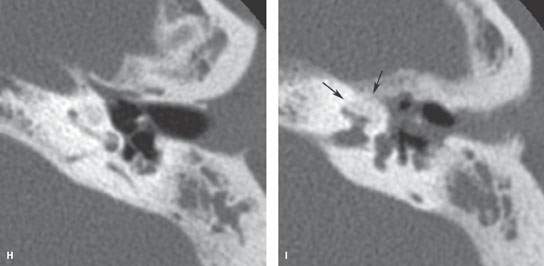

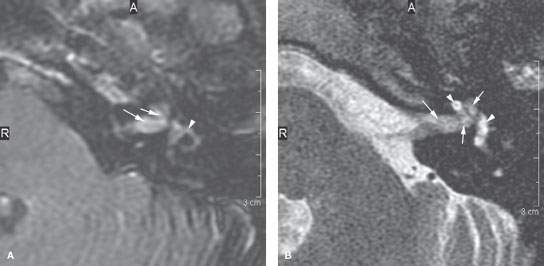

Acute suppurative (pyogenic) bacterial infections of the middle ear and mastoid can cause inner ear dysfunction due to involvement of the membranous labyrinth and/or cochleovestibular nerve (CVN); this generally is found to be associated with meningitis and is a medical emergency at the time of acute disease. The delayed effect of such inner ear infection is often a chronic, fibro-osseous obliterative labyrinthitis (Fig. 117.1). Chronic infections such as skull base osteomyelitis (Chapter 115), Lyme disease, and syphilis also may cause inner ear dysfunction due to labyrinthitis (Fig. 117.2). The most common infectious condition causing labyrinthitis may be viral neuritis, but this is only occasionally demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as labyrinthine, cranial nerve, and/or Scarpa ganglion enhancement. Viral neuritis is typically a presumptive diagnosis that is confirmed clinically by its response to therapy and/or associated clinical findings (Fig. 117.3). This and bacterial labyrinthitis may be primary in the labyrinth, seeded from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or a source of secondary meningitis or meningoencephalitis. These infectious diseases may all progress to a stage of chronic obliterative labyrinthitis (Fig. 117.4).

Other inflammatory conditions that cause labyrinthitis include sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, Langerhans histiocytosis, and autoimmune diseases (Fig. 117.5) and traumatic or hemorrhagic labyrinthitis (Fig. 117.6) are inflammatory but not infectious. These conditions may require no treatment or nonspecific anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapy. This varied group of conditions occasionally presents as an isolated labyrinthitis deficit, but they often involve the labyrinth together with the central nervous system (CNS) and other organ systems. For the purposes of this chapter, these conditions are grouped into the two broad categories of infectious and noninfectious inflammatory diseases since the etiologies vary considerably while the imaging features related to the labyrinth itself vary little.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Bacterial meningitis in children has been reported to cause permanent hearing loss in 10.0% to 13.9%.1,2 It is the most common cause of postnatal acquired sensorineural hearing loss.

Other infections, except for viral disease, are all relatively uncommon causes of labyrinthine dysfunction.

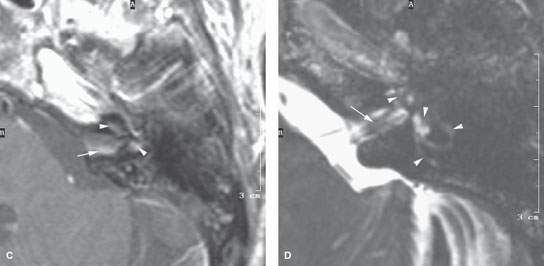

FIGURE 117.1. Several patients with labyrinthitis of infectious origin. A, B: Patient 1 presented with acute otomastoiditis and developed meningitis and hearing loss. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows enhancement in the mastoid, extending to the labyrinth (arrow). Most likely, the spread of infection occurred through the round and/or oval window (arrowhead). In (B), on steady state images, there is signal loss within the labyrinth (arrows) and thickening of the nerves in the internal auditory canal (IAC) (arrowheads). C–G: Patient 2 with labyrinthitis secondary to pasturella meningitis. In (C) and (D), the contrast-enhanced T1W images show multifocal labyrinthine (arrows), meningeal, and perineural enhancement (arrowheads) corresponding to labyrinthitis in the acute stage characterized by inflammatory cells and bacteria in the perilymphatic spaces. The portal of entry is possibly from meningitic spread via the cochlear aperture reflected by the enhancement in the IAC. The steady state image in (E) shows little abnormality, likely reflecting the exudative nature of the labyrinthine disease. In (F) and (G), subacute pyogenic labyrinthitis on the non–contrast-enhanced T1W image (F) shows high signal intensity within the labyrinth (arrows) compared to fluid intensity of cerebrospinal fluid possibly corresponding to proteinaceous fluid content. The contrast-enhanced T1W image in (G) shows multifocal labyrinthine enhancement (arrows) that essentially is indistinguishable from the more acute changes present in Patient 1. H–M: Patient 3 with hemorrhagic meningitis and labyrinthitis with acute hearing loss. In (H) and (I), the non–contrast-enhanced T1W images show high signal intensity within the labyrinth, likely due to blood products. In (J) and (K), the contrast-enhanced T1W images show high signal intensity within the labyrinth, unchanged in some areas but obvious enhancement manifesting in the semicircular canals compared to the non–contrast-enhanced images. In (L) and (M), the T2-weighted images show high signal intensity within the labyrinth to be mainly altered within the vestibule (arrow in M).

The prevalence of labyrinthitis in patients with underlying or causative disease will follow that of the population at risk for those diseases; for instance, younger children and young adults are at more risk for labyrinthine dysfunction secondary to acute or chronic otomastoiditis, and the same is true for diabetics and those with necrotizing otitis externa (NOE) (Fig. 117.2). The risk of labyrinthine dysfunction from infections such as Lyme disease and schistosomiasis follows that of likely exposure to the infectious vector. Involvement with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (Fig. 26.10) and occasionally other infections is related to immune suppression—either acquired or iatrogenic.

The prevalence and epidemiology of the noninfectious inflammatory diseases that may cause labyrinthitis are discussed in conjunction with those specific entities in Chapters 17 through 20 and 26.

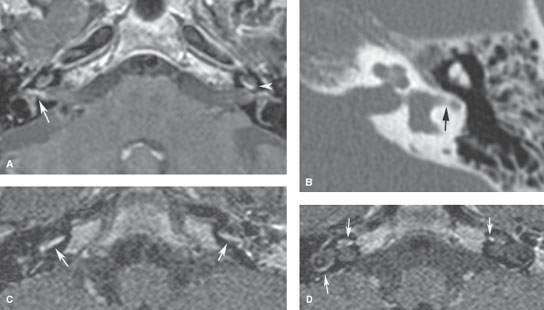

FIGURE 117.2. Four patients with chronic labyrinthitis. A–C: Patient 1 with labyrinthitis secondary to skull base osteomyelitis. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) magnetic resonance (MR) image shows abnormal enhancement of the labyrinth (white arrows) and within the internal auditory canal (IAC) and cerebellopontine angle (CPA) (white arrowheads). There is a possible communication between the disease within the middle ear and mastoid and the lateral semicircular canal (black arrowhead). In (B), the T2-weighted MR image shows loss of signal throughout the labyrinth and IAC, with the signal of fluid replaced by the signal of abnormal tissue (arrows). Only the apical and middle turns of the cochlea are spared (arrowhead). In (C), the computed tomography (CT) study at approximately the same level as seen in (A) and (B) shows erosion of bone over the lateral semicircular canal (arrow), explaining how the infectious process invaded the labyrinth. D: Patient 2 had known osteoradionecrosis after treatment for a parotid adenocarcinoma. This was complicated by acute labyrinthitis causing diffuse enhancement of the petrous bone as well as a subdural empyema (arrowhead) in the CPA. E: In Patient 3, the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows enhancement of the otomastoid inflammatory changes spreading into the vestibular system (arrow) through erosion of the posterior semicircular canal. F–I: Patient 4 shows that chronic otomastoid disease may progress to a stage of chronic obliterative labyrinthitis (arrows), as seen in this patient with cholesteatoma. On coronal CT (F), a pars tensa cholesteatoma with erosion of the scutum and ossicles is seen. Secondary labyrinthitis resulted in thickening of the spiral lamina in the basal turn (G) and complete ossification of the second and apical turn of the cochlea (F, H, I). Refer to Figure 117.4 for more examples. (continued)

Clinical Presentation

Patients will generally present with hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, or balance problems. When acute, this may be dominated by nonspecific symptoms such as nausea and vertigo or may resemble a cerebral infarction in evolution with symptoms such as a depressed mental status with vertigo. The symptoms may be preceded and sometimes masked by the underlying disease.

Nystagmus—spontaneous or positional provoked—may be present on physical examination. A thorough neurotologic evaluation and audiometry will often provide localization of the problem.

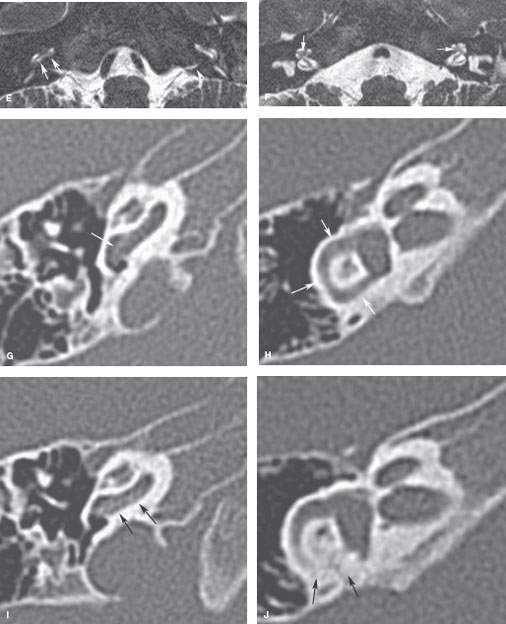

FIGURE 117.3. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in two patients with viral labyrinthitis. A–B: Patient 1 is immune compromised due to transplantation. The patient presented with signs of labyrinthitis. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows abnormal enhancement within the internal auditory canal (IAC), extending into the basal turn of the cochlea (arrows) and then involving the vestibular system (arrowhead). In (B), the T2-weighted (T2W) image shows the normal fluid signal within the IAC and cochlea largely replaced by abnormal tissue (arrows) with relative sparing of a portion of the cochlea and the vestibule (arrowheads). C, D: Patient 2 presenting with signs and symptoms of labyrinthine dysfunction. The patient was not immune compromised. In (C), the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows abnormal enhancement within the IAC (arrow) and the vestibule and possibly the cochlea (arrowheads). In (D), the T2W image shows abnormal loss of signal around the divisions of the cochleovestibular nerve in the IAC (arrow) and loss of signal within the cochlea and vestibular system. (NOTE: The common feature suggesting a viral etiology in this situation is the involvement of both the labyrinth and nerve. Viral neuritis usually due to a herpes virus may be isolated to the nerve. When no other etiology is apparent clinically, a pattern of involvement of both the nerve, especially distally within the IAC and the labyrinth, suggests a viral etiology.)

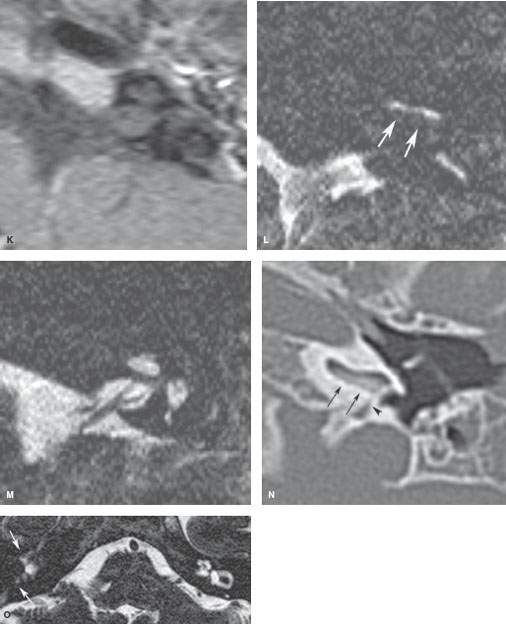

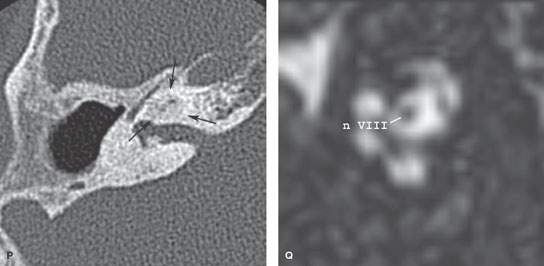

FIGURE 117.4. Imaging findings in four patients with labyrinthitis ossificans. A, B: Patient 1 developed severe sensorineural hearing loss in the right ear and deafness in the left shortly after a pneumococcal meningoencephalitis. In (A), contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) shows enhancement of the vestibular nerve on the right and within the cochlea on the left. In (B), computed tomography (CT) shows only a subtle increase in density within the horizontal semicircular canal (arrow), while the cochlea is still patent. The enhancement might be due to granulation tissue formation in the fibrous stage of labyrinthitis. (NOTE: This case illustrates how subtle these changes may appear on CT studies.) C–J: Patient 2 illustrates early changes and rapid progression of fibro-osseous changes in labyrinthitis ossificans. MR performed 6 weeks after Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis shows bilateral labyrinthine enhancement (C, D) and signal loss on steady state images in the right proximal scala tympani (arrows in E), close to the orifice of the cochlear aqueduct (arrowhead in E) and around the modiolus (arrows in F). On corresponding CT images, subtle thickening of the spiral lamina and subtle haziness within the horizontal semicircular canal are seen as the earliest signs of labyrinthitis ossificans (white arrows in G and H). This clearly underestimates the extent of disease. A follow-up CT after 7 weeks shows rapid progression of the bony proliferative changes (black arrows in I and J). K–N: Patient 3 with labyrinthitis in the fibro-osseous stage. MR performed 7 months after streptococcal meningitis shows no enhancement within the labyrinth (K) but does show signal loss in the proximal scala tympani (arrows) of the left cochlea (L, M). This signal loss corresponds to fibro-osseous changes on CT (N), close to the orifice of the cochlear aqueduct (arrowhead). O–Q: Patient 4. Ossifying labyrinthitis may end in total obliteration of the cochlea, as seen in the right ear on MR (O) and CT (P). Long-standing deafness may lead to atrophy of the cochlear nerve in (Q); the cochlear nerve measures about 0.9 mm, suggesting some atrophy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree