LACRIMAL GLAND: BENIGN AND MALIGNANT TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are in the critical pathway for evaluating the signs and/or symptoms that are related to a lacrimal gland–origin neoplasm.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are extremely useful for narrowing the differential diagnosis of tumors of the lacrimal gland.

- Imaging with magnetic resonance or computed tomography will help establish whether the disease process is localized or possibly related to systemic disease.

- If a lesion is not to be biopsied or removed, magnetic resonance or computed tomography should be used to establish whether its rate of growth is consistent with a benign or malignant process.

Any orbital mass or disease process may be approached by first establishing whether it is preseptal (Chapters 70 and 71) or postseptal (Chapters 57–60, 62, and 64). If postseptal, it should be established as a process arising primarily intraconally (Chapters 57–60), extraconally (Chapters 62 and 64), or transcompartmentally. This chapter considers lacrimal gland tumors that by anatomic definition are both preseptal and postseptal and extraconal. These tumors, when malignant, may spread across the other orbital compartments and related spaces.

The lacrimal gland may be thought of as a salivary gland when considering the likely etiology of a unilateral tumor. In that regard, the tendencies for tumor involvement are most like the submandibular gland as opposed to the parotid gland. Bilateral tumor involvement is almost always due to lymphoma, although that tumor may be unilateral or so asymmetric that it appears to be unilateral.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

The relevant anatomy of the bony orbit, muscle cone, and related neurovascular structures is discussed in detail in Chapter 44. In particular, the anatomy of the palpebral and orbital portions of the lacrimal gland and the gland’s relationship to the orbital septum should be reviewed.

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The orbit, eye, and optic nerve and sheath are studied with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) techniques described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45. Specific CT protocols by indications are detailed in Appendix A. Specific MR protocols by indications are outlined in Appendix B. Almost all studies to investigate the lacrimal gland tumors are done with contrast.

Pros and Cons

Diseases of the lacrimal gland are studied primarily with CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is more definitive in its rendering of the gland.

CT may be used first if a dermoid or epidermoid cyst is suspected since it may have a significant bony component. Supplemental CT may need to be done if bone involvement or related sinonasal pathology needs to be evaluated definitively.

Either study is really sufficient for a good evaluation of the lacrimal gland.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Benign and Malignant Tumors

Etiology

Approximately one half of lacrimal gland tumors are malignant (Figs. 66.1 and 66.2); of these, most are epithelial and the remainder lymphoproliferative tumors (Figs. 66.3 and 66.4). Benign mixed tumors are the most common benign intraglandular tumor (Fig. 66.5). Rarely, vascular tumors, such as cavernous or epithelioid hemangioma (Fig. 66.6), hemangioendothelioma, or hemangiopericytoma arise in the lacrimal fossa.1,2 Dermoid cysts may present as lacrimal gland lesions, although they arise from intraorbital inclusions of ectodermal elements (Fig. 66.7). Orbital nerve sheath tumors presenting in the lacrimal fossa region are rare outside of those related to neurofibromatosis type 1. Mucoepidermoid, adenoid cystic, and less well-differentiated adenocarcinomas are common lacrimal gland malignancies. The remaining masses include B-cell lymphomas, metastases (usually from breast or lung cancers), and more rare forms of carcinoma.3

Prevalence and Epidemiology

These are sporadic, fairly rare tumors presenting in both adult and pediatric patients but are far more common in middle-aged adults. There are no significantly predisposing factors except of neurofibromatosis in those patients with nerve sheath tumors.

Clinical Presentation

Tumors typically present as a painless orbital mass, most typically in the upper outer quadrant. Pain is more commonly seen in nonneoplastic, inflammatory orbital processes such as pseudotumor but can be an important sign of perineural invasion for adenoid cystic carcinoma. Such malignant lesions may also present with sensory loss along the course of the lacrimal nerve. The presentation may be bilateral (i.e., in lymphoma) but noticed more on one side than the other. The eye may be displaced inferior and medially.

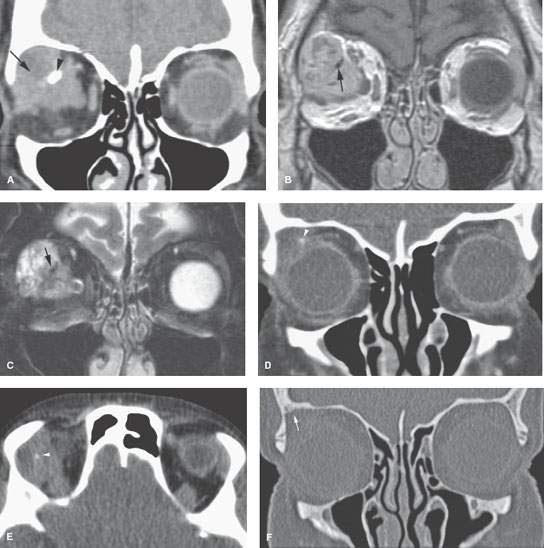

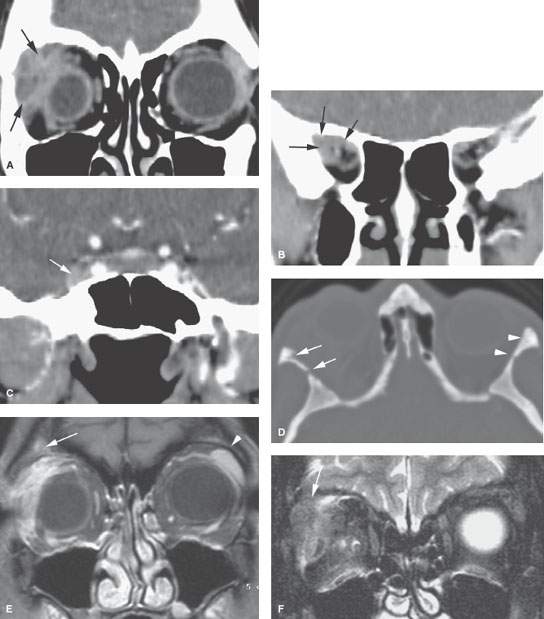

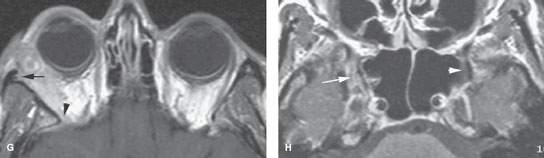

FIGURE 66.1. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of three patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. A–C: Patient 1. In (A), contrast-enhanced CT study shows an infiltrating mass (arrow) with a calcification (arrowhead). The latter could be mistaken for a phlebolith. In (B), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows this to be an irregularly enhancing mass with the calcification seen as a signal void (arrow). In (C), the T2-weighted image shows this to be a solid mass with some macro- or microcystic elements brighter than others; thus, the appearance is not consistent with a vascular malformation. Again, the calcification appears as a signal void (arrow). D–G: Patient 2. In (D) and (E), CT at a soft tissue window shows enlargement of the right lacrimal gland with a small calcification (arrowhead). In (F) and (G), CT at a bone window reveals subtle erosion of adjacent bone (arrow), which is suggestive of a malignant tumor. H–J: Patient 3. In (H), enlargement of the left lacrimal gland on a contrast-enhanced T1W fat-suppressed image. The extension toward the superior orbital fissure (white arrow) was initially overlooked. The tumor was resected, and an adenoid cystic carcinoma was found. In (I) and (J), a postoperative MRI was performed because of persistent pain, revealing progressive perineural growth along V1 toward the superior orbital fissure (white arrow) and V2 (white arrowhead) and into the trigeminal ganglion and cistern (black arrow). (Parts H–J courtesy of Nicole Freling, Academic Medical Center Amsterdam, the Netherlands.)

Pathophysiology and Patterns of Disease

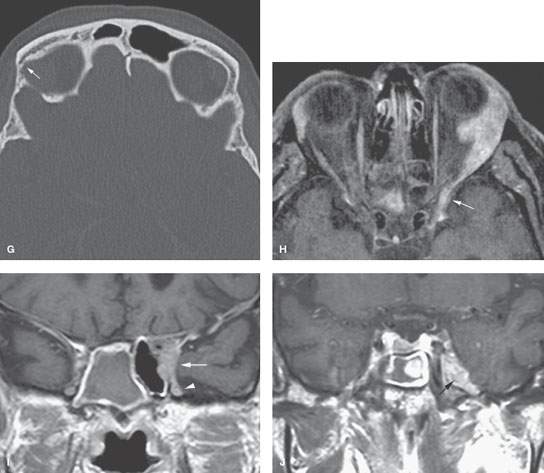

These tumors grow in a fashion typical of benign and malignant tumors as described in Chapter 21. Benign tumors may cause bone to remodel; otherwise, they slowly enlarge and displace surrounding structures. Malignant tumors may grow relatively rapidly in a transcompartmental fashion and invade bone and demonstrate perineural spread along V1 branches toward the superior orbital fissure or along the zygomaticotemporal branch of V2. Intracranial spread is unusual (Figs. 66.1 and 66.2). Lymphadenopathy is very unusual at presentation but may be seen in recurrent carcinoma, with the risk being to facial, parotid, and level 1 nodes as first echelon sites.

Manifestations and Findings

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The general morphology of benign and malignant glandular neoplasms as seen on CT and MRI is described in Chapter 22.

Differential Diagnosis

From Clinical Data

One half of unilateral masses of the lacrimal gland will be tumors. The remainder will be expressions of benign inflammatory disease such as sarcoidosis, Sjögren disease, and pseudotumor (Chapter 65). Benign or malignant glandular epithelial tumors present as unilateral, usually painless, masses. Lymphoma, if associated with systemic disease, is often bilateral. Asymmetric glandular involvement with lymphoma may mimic unilateral disease (Figs. 66.3 and 66.4). When bilateral, findings of sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, or other systemic disease become as likely as lymphoma. The presence of pain and a red eye favor an inflammatory etiology, although adenoid cystic carcinoma or other malignancy must be kept in the differential.

FIGURE 66.2. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) of a patient with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the lacrimal gland. A: Coronal CT study shows the highly infiltrative mass in the lacrimal fossa (arrows). B: The mass is shown to infiltrate the posterior orbit near the orbital apex (arrows). C: Coronal reformations at the cavernous sinus show tumor to have extended through the superior orbital fissure, likely along the V2 (arrow). D: There is erosion of the lateral orbital wall (arrows) compared to the left (arrowheads). E–H: MR images of the same patient. In (E), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) fat-suppressed image shows the infiltrating mass in the lacrimal fossa to likely invade bone (arrow) in comparison to the normal lacrimal gland and bone on the opposite side (arrowhead). In (F), the T2-weighted fat-suppressed image shows likely orbital roof invasion (arrow) by what appears to be a largely solid infiltrating mass. (G), the contrast-enhanced T1W image shows the mass to invade the entire lateral aspect of the orbit to the orbital apex (arrowhead) and to likely invade the lateral orbital bony wall (arrow). In (H), on a contrast-enhanced T1W axial image, perineural spread along V2 (arrow) is confirmed compared to the normal foramen rotundum region (arrowhead).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree