, David C. ShonkaJr.2, Max Wintermark3 and Sugoto Mukherjee4

(1)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

(2)

Division of Head and Neck Surgical Oncology, Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(3)

Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

(4)

Division of Neuroradiology, Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Abstract

This chapter will focus on the imaging evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx. Although several other malignant neoplasms can occur in the larynx, these are uncommon and will not be addressed in detail. Imaging of traumatic and inflammatory processes and vocal cord paralysis is also briefly discussed.

5.1 Introduction

This chapter will focus on the imaging evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx. Although several other malignant neoplasms can occur in the larynx, these are uncommon and will not be addressed in detail. Imaging of traumatic and inflammatory processes and vocal cord paralysis is also briefly discussed.

5.2 Anatomy (Box 5.1)

The laryngeal skeleton is comprised of the hyoid bone, three unpaired (epiglottis, thyroid, cricoid), and four paired (arytenoid, corniculate, cuneiform, triticeous) cartilages (Fig. 5.1). The corniculate and cuneiform cartilages (located along the aryepiglottic folds) and the triticeous (located in the thyrohyoid membrane) are of no clinical significance. The epiglottis is attached to the laryngeal skeleton by the hyoepiglottic and thyroepiglottic ligaments. The mucosa of the lingual surface is contiguous with that of the vallecula and tongue base (Fig. 5.1). The epiglottis has little resistance to tumor invasion.

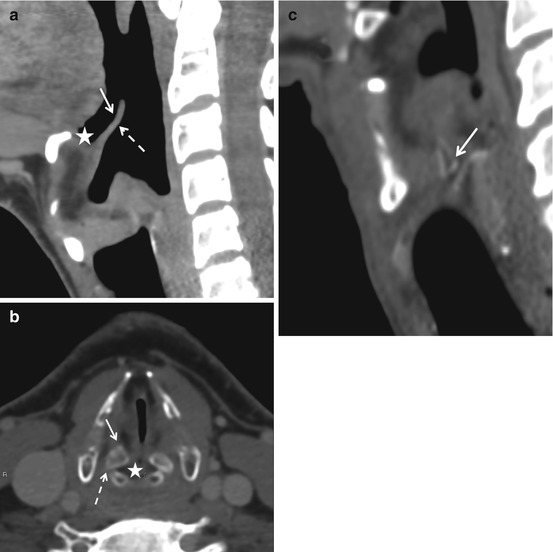

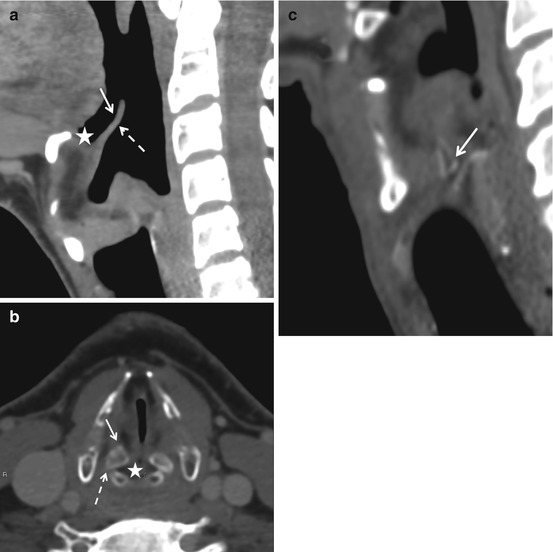

Fig. 5.1

The laryngeal cartilages. (a) The epiglottis has a lingual (solid arrow) and laryngeal (dashed arrow) surface. The valleculae (asterisk) lie between the lingual surface and the base of the tongue. (b) The thyroid cartilage can be variably calcified/ossified. The arytenoid cartilages are comprised of a vocal (solid arrow) and a muscular process (dashed arrow). The vocal processes provide attachment to the true cords. The mucosa between the arytenoid cartilages is the inter-arytenoid area (asterisk). The cricoarytenoid joint space is best seen on the sagittal plane (c). Note that the height of the cricoid ring is greater posteriorly than anteriorly

The thyroid cartilage is comprised of two laminae attached at the midline. Superior and inferior cornua project from the posterior edge of each lamina. The thyroid cartilage is connected to the hyoid bone by the thyrohyoid membrane, which is pierced by the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle; this provides a pathway for extralaryngeal tumor spread. The thyroid cartilage is connected to the cricoid cartilage by the cricothyroid membrane. The inferior cornua articulate with a small facet on each side of the cricoid cartilage. In young people, the thyroid cartilage, like other laryngeal cartilages, is of soft tissue density on CT scan. It mineralizes with age in a central to peripheral direction. Ossified foci of cartilage often contain fatty marrow (Fig. 5.1).

The cricoid cartilage is shaped like a signet ring and has an anterior arch and a flat posterior quadrate lamina (Fig. 5.1). Along the superior edge of the lamina on either side of the midline are two facets for articulation with the pyramidal arytenoid cartridges. The cricoid cartilage is the foundation upon which the framework the larynx rests. Tumor involvement of this structure precludes any type of voice preservation surgery.

The arytenoid cartilages articulate with the cricoid cartilage by true synovial joints, which are susceptible to all the disease processes that may afflict synovial joints elsewhere in the body. An anterior vocal process provides attachment to the vocal ligament. The lateral muscular process provides attachment to the lateral and posterior cricoarytenoid muscles (Fig. 5.1). With age, the arytenoid cartilage can undergo mineralization which may be markedly asymmetric.

The aryepiglottic folds arise from each lateral edge of the epiglottis and extend to the arytenoids. They are supported by a fibrous fascial sheet called the quadrangular membrane. The lower free edge of the aryepiglottic fold forms the false vocal cord, and the associated edge of the quadrangular membrane forms the ventricular ligament. The aryepiglottic folds also form the medial margin of the paraglottic spaces (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.2

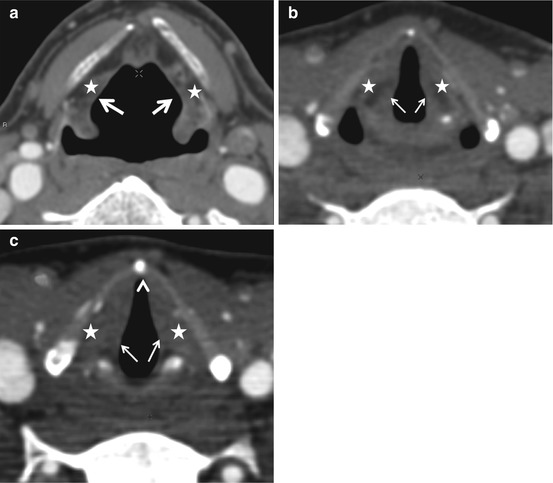

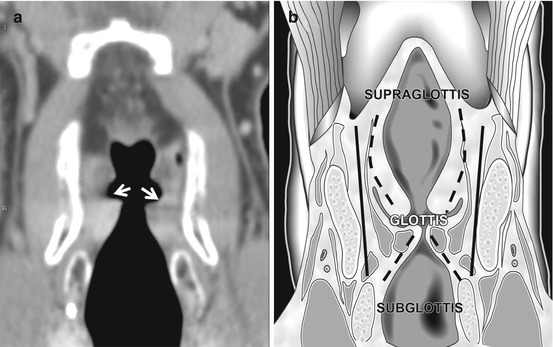

(a) The aryepiglottic folds (arrows, a) descend on either side from the lateral margins of the epiglottis. The AE folds are supported by the conus elasticus. Their free edges form the false cords (b). The false cords contain fat as opposed to the true cords which are nearly entirely comprised of the thyroarytenoideus muscle (arrows, c). The arrowhead in (c) points to the anterior commissure. The asterisks indicate the paraglottic spaces

Each true vocal cord is comprised of mucosa covering the fibrous vocal ligament medially and the thyroarytenoid (vocalis) muscle laterally. The anterior commissure is an important anatomic landmark where the fibers of the vocal ligament directly pierce the thyroid cartilage. The absence of a protective perichondrium in this location permits tumors to access the thyroid cartilage (Fig. 5.2). The space between the true and false vocal cords is the laryngeal ventricle. The saccule/appendix of the laryngeal ventricle is lined by mucus glands and may extend into the paraglottic space. The posterior commissure is the region between the two arytenoid cartilages (inter-arytenoid area) (Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3

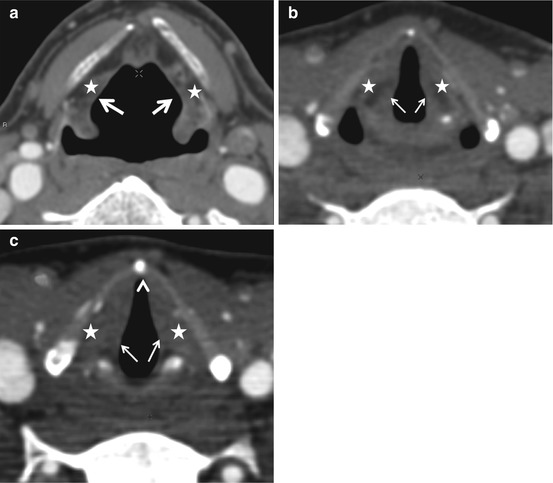

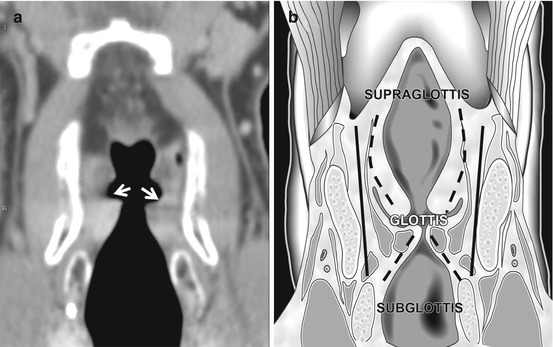

The laryngeal ventricle and the divisions of the larynx. The laryngeal ventricle (arrows, a) is the space between the false and the true cords and is best seen on a coronal view. The glottis includes the ventricle and about 1 cm of the airway inferiorly. The subglottis extends from this point to the lower margin of the cricoid cartilage. The paired dashed upper lines in (b) correspond to the conus elasticus and the inferior pair of dashed lines, to the cricovocal membrane. Note that the paraglottic spaces run nearly the entire length of the larynx (black lines in b) and are limited inferiorly by the cricovocal membrane

The conus elasticus is a thick membrane that extends from the vocal ligament to the upper margins of the cricoid cartilage. This membrane is an effective barrier to inferior submucosal spread of glottic malignancy (Fig. 5.3).

It is crucially important to understand the radiology of two spaces in the larynx (Fig. 5.4). The preepiglottic space is a fat-containing midline space located anterior to the epiglottis, posterior to the hyoid bone and thyrohyoid membrane, and contained between the hyoepiglottic ligament superiorly and the thyroepiglottic ligament inferiorly (Fig. 5.4). The preepiglottic space continues on each side as the paraglottic spaces which are bounded laterally by the thyroid cartilage and thyrohyoid membrane and medially by the quadrangular membrane (aryepiglottic folds). The space spans the entirety of the supraglottis and glottis and is limited interiorly by the conus elasticus. Paraglottic space involvement allows submucosal extension of laryngeal malignancy, which may not be visible on endoscopy; it upstages laryngeal cancer and is associated with increased risk of regional metastatic lymphadenopathy. Tumors that arise outside of the larynx may also involve these spaces: the preepiglottic space may be involved by base of tongue malignancy, and the paraglottic space may be involved by invasive pyriform sinus cancers.

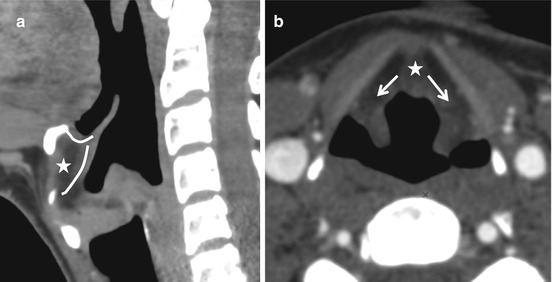

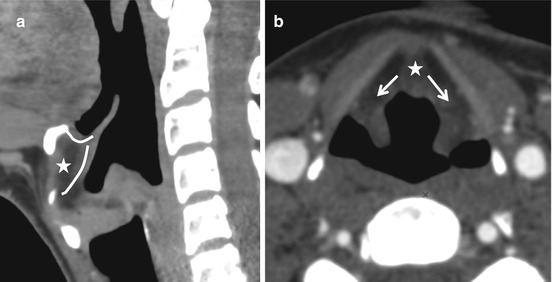

Fig. 5.4

The laryngeal spaces. The preepiglottic space (asterisk in a and b) is enclosed between the hyoepiglottic and thyroepiglottic ligaments and contains a pad of fat. It is best seen on a sagittal view. The preepiglottic space is contiguous with the paraglottic spaces on either side (arrows, b)

The larynx is divided into the supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis. The supraglottis is cephalad to a plane across the apex of the ventricles. The glottis lies between this plane and a plane drawn 1 cm more caudal; it encompasses the floor of the ventricle, the anterior and posterior commissures, and the true vocal cords. The subglottis extends from the second plane to the inferior margin of the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 5.3).

The supraglottic larynx is drained bilaterally by a rich lymphatic network, and supraglottic squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) tend to spread to level II and III lymph nodes bilaterally. The glottis, especially the true vocal cord, is poorly served by lymphatics. Small true vocal cord tumors almost are never associated with cervical lymphadenopathy. The subglottis drains to central compartment (level VI) lymph nodes.

The recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN), a branch of the vagus, innervates all the laryngeal muscles except for the cricothyroid, which is supplied by the superior laryngeal nerves. The right RLN loops under the right subclavian artery before ascending along the tracheoesophageal groove to enter the larynx. The left RLN loops under the arch of the aorta.

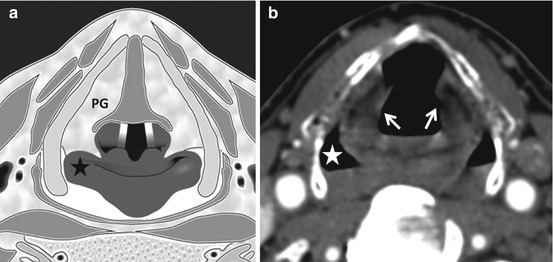

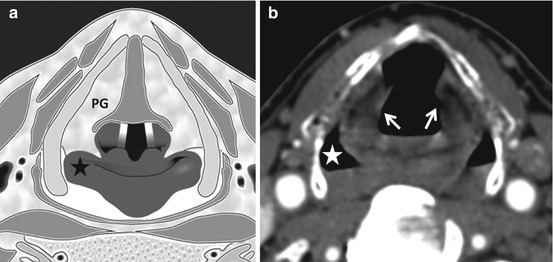

The hypopharynx is divided into three subsites: the postcricoid area, the posterior pharyngeal wall, and the pyriform sinuses (Fig. 5.5). The pyriform sinuses may be imagined as inverted cone-shaped outpouchings of the hypopharynx lateral to the larynx. The medial walls of the pyriform sinuses are formed by the aryepiglottic folds. The lateral walls are formed by the thyroid cartilage. It is important to note that the paraglottic space lies directly anterior to the pyriform sinuses. The apices of the pyriform sinuses lie roughly at the level of the superior margin of the cricoid cartilage; cancer in this location is almost invariably treated by a total laryngectomy due to the need for cricoid resection to obtain adequate margins. As the cricoid cartilage is the structural foundation of the larynx, its removal necessitates total laryngectomy.

Fig. 5.5

The pyriform sinuses. The pyriform sinuses (asterisks in a and b) are paired outpouchings of the hypopharynx, sandwiched between the aryepiglottic folds (arrows, b) and the thyroid cartilages. It is important to note that the paraglottic spaces (PG) are immediately anterior to the pyriform sinuses and tumor spread between the larynx and hypopharynx can easily occur here

Box 5.1. Key Anatomical Terms

Divisions

Supraglottis

Subsites

Epiglottis – suprahyoid (tip, lingual, and laryngeal surfaces)

Epiglottis – infrahyoid

Aryepiglottic folds – laryngeal surface

False vocal cords

Arytenoid cartilages

Glottis

True vocal cords

Anterior commissure

Posterior commissure (inter-arytenoid area)

Subglottis

Cartilages

Unpaired

Epiglottis

Thyroid

Cricoid

Paired

Arytenoid

Corniculate

Cuneiform

Triticeous

Ligaments

Hyoepiglottic

Thyroepiglottic

Ventricular ligament – false vocal cord

Vocal ligament – true vocal cord

Spaces

Preepiglottic space

Paraglottic space

Membranes and fascia

Quadrangular membrane

Conus elasticus

Thyrohyoid membrane

Cricothyroid membrane

Joints

Cricoarytenoid joints

Cricothyroid joints

Muscles

Thyroarytenoideus – forms bulk of true cords

Posterior and lateral cricoarytenoid – antagonistic muscles that abduct and adduct the TVCs

5.3 Imaging Evaluation

Plain radiography plays little to no role in the evaluation of laryngeal pathology, except perhaps in the localization of foreign bodies. Computed tomography is mainstay of laryngeal imaging and is best performed on helical scanners where the entire larynx may be covered in one breath hold. It is important to obtain axial planes along the axis of laryngeal ventricles in order to be able to assess anatomy accurately. This is easily achieved by educating the technologist to reconstruct a set of axial images parallel to the C2–C3 intervertebral disc space. This space is roughly parallel to the plane of the ventricles. Coverage must extend from the skull base to the aortopulmonary window, especially when vocal cord paralysis is being evaluated. Intravenous contrast improves tumor delineation and characterization of lymph nodes.

MRI is rarely used for laryngeal imaging, but may be valuable when assessment of laryngeal cartilage invasion is of critical importance. A typical MR study should consist of precontrast axial and sagittal T1-weighted sequences to depict low-signal-intensity tumor against a background of high-intensity fat contained in ossified cartilage marrow and in the preepiglottic and paraglottic spaces. Fat-suppressed T2-weighted sequences enable detection of high-signal-intensity tumors amid dark suppressed fat. Post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighted obtained in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes highlight enhancing tumor and enable differentiation from non-enhancing edema. MR images are often degraded by respiratory and pulsation artifact. In routine clinical practice, most questions can be answered by CT alone.

PET/CT does not aid significantly in establishing the extent of primary laryngeal tumors. It is also not definitively useful in pretreatment evaluation for regional metastasis, which can be adequately accomplished by standard CT and clinical exam. PET/CT may have value in staging advanced tumors that are at risk for distant metastasis and in the evaluation of recurrent disease in the posttreatment neck.

5.4 Squamous Cell Carcinoma

5.4.1 Radiographic Staging

Accurate interpretation of imaging for laryngeal SCC rests upon a thorough understanding of the TNM staging criteria (Box 5.2). The task of the radiologist is not primarily to diagnose SCC but to assist in staging it. Clinical T stage is assigned based on data obtained from endoscopic evaluation and cross-sectional imaging. Although tumors of the supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis are staged slightly differently, the principles behind such staging, such as extent of tumor, impairment of cord mobility, cartilage invasion, and involvement of extralaryngeal structures remain the same. Key concepts in the imaging evaluation are:

1.

Subsite involvement: The supraglottic subsites include the suprahyoid epiglottis, the infrahyoid epiglottis, the aryepiglottic folds, the false vocal cords, and the arytenoids. Involvement of more than one subsite indicates at least a T2 lesion (Fig. 5.6). Although endoscopy in most cases can assess the number of subsites involved accurately, the radiologist must attempt to accurately describe all locations involved, especially when bulky tumors prevent adequate visualization.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Fig. 5.6

T2 supraglottic squamous cell carcinoma. Note the nodular soft tissue thickening of the mucosa of the left aryepiglottic fold (arrow) and root of the epiglottis (white arrowhead

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree