LARYNX: BENIGN NONINFLAMMATORY MASSES AND TUMORS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are very valuable diagnostic tools for the evaluation and planning of the next steps in the diagnosis and management of submucosal laryngeal masses that are eventually shown to be benign.

- Such imaging can help to avoid possible complications such as excessive bleeding from endoscopic biopsy.

- Computed tomography can replace endoscopy and bronchoscopy in highly selected patients with recurrent papillomatosis.

After physical examination, it is often difficult to decide whether an area of swelling is neoplastic, inflammatory, traumatic, or degenerative. Even after biopsy, the etiology may remain obscure. For example, a “singer’s nodule” may simply disappear with voice rest, but biopsy at various stages will reveal anything from polypoid degeneration of the margin of the vocal cord to vascular fibrous tissue to an appearance impossible to tell from a fibroma.

Most benign tumors or focal areas of swelling in the larynx will have a nonspecific imaging appearance. On occasion, imaging findings will be specific enough to allow an etiologic or, rarely, a very likely specific tissue diagnosis. The most fitting and usual use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is to show the extent of the lesion and identify the likely etiology of a submucosal mass.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

A thorough knowledge of laryngeal anatomy and anatomic variations in each of the following areas is required for the evaluation of benign, noninflammatory masses of the larynx. This anatomy is presented in detail with the introductory material on the larynx, hypopharynx, cervical esophagus, and infrahyoid neck in general.

Evaluation of laryngeal and related structures frequently involved with contiguous disease in these conditions should include the following:

- Larynx, including the laryngeal skeleton, deep tissue spaces within the larynx, mucosal landmarks, and functional structures within the larynx (Chapter 201)

- Hypopharynx (Chapter 215)

- Tongue base region and low oropharyngeal wall (Chapter 190)

- Cervical esophagus and its junction with the postcricoid portion of the hypopharynx (Chapter 221)

- Trachea (Chapter 209)

Evaluation of Extralaryngeal Spread

- Visceral compartment of the neck and related fasciae (Chapter 149)

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The larynx is studied in essentially the same manner for benign masses of known or uncertain etiology as it is for the evaluation of known or suspected laryngeal cancer. The principles of using these studies are reviewed in Chapters 201 and 206. Specific problem-driven protocols for CT and MRI of the larynx and hypopharynx are presented in Appendixes A and B, respectively.

There is little or no use for ultrasound in studying these masses.

There is a limited role for catheter angiography in lesions where the physical examination and imaging with CT angiography and/or MRI suggests that they are vascular in origin or very hypervascular.

Radionuclide studies are generally not useful in benign masses of the larynx.

Pros and Cons

Evaluation of Submucosal or Other Masses of Uncertain Etiology

Benign masses limited to the larynx often mimic the initial presentation of larynx cancer. Any mass, regardless of etiology, that is suspicious for deep infiltration or cancer should be studied primarily with CT if imaging is desired as part of the evaluation (Fig. 205.1). MRI can be used initially if preferred but is much more likely to be significantly degraded and sometimes nondiagnostic due to motion artifacts. Supplemental magnetic resonance (MR) study, in the situations where it might add meaningful incremental data, is best directed by CT findings to a localized area of interest where its strengths related to better soft tissue contrast resolution may be exploited.

Integrity of the Airway

In any imaging study of the larynx, the diseased condition must be evaluated for its effect on the airway. The anatomic status of the airway, as well as the risk of any acute adverse complication, such as the potential for rapidly progressive airway obstruction either by the mass or a potential airway complication that might arise as a result of biopsy, should be reported (Figs. 205.2 and 205.3). For instance, biopsy of an unanticipated laryngeal paraganglioma could lead to an unfortunate amount of hemorrhage and aspiration of blood. Virtual endoscopic processing of images can help to obviate some endoscopic and bronchoscopy procedures (Fig. 205.4) for at least gross airway assessment even though such virtual anatomic studies lack dynamic and functional information.

Evaluation of Laryngeal Dysfunction Due to Submucosal Masses

Some patients have processes predominantly occurring beneath intact mucosa. These diseases may begin on the mucosa within the laryngeal ventricle and the false vocal cord and spread within the paraglottic space or primarily arise from the laryngeal cartilages (Figs. 205.5 and 205.6). About half of all submucosal laryngeal masses will be laryngoceles. This is discussed more fully in conjunction with laryngoceles (Chapter 203). About one quarter will be entirely submucosal squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA) or other rare malignancies (Chapter 206). The other 25% or less will be the benign masses discussed in this chapter.

Vocal Cord Dysfunction and Weakness

Benign masses can affect true vocal cord function. Imaging can be useful in showing a likely benign mass as the cause for such true vocal cord dysfunction (Figs. 205.1, 205.2, and 205.5–205.9).

Controversies

Some believe that MRI should be the primary study for evaluating the larynx in most conditions. This is discussed in more detail in the introductory material about the larynx and hypopharynx (Chapter 201).

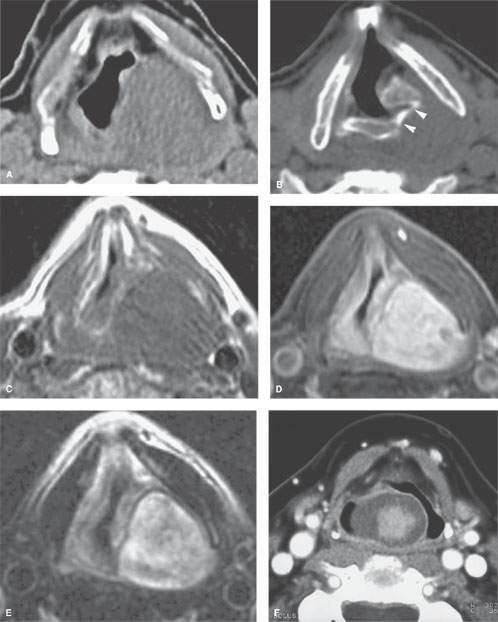

FIGURE 205.1. Two patients with laryngeal nerve sheath tumors. A–E: Patient 1. Schwannoma of the larynx arising likely from the aryepiglottic fold. In (A), a non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) image. In (B), a non–contrast-enhanced CT image at the level of the pyriform sinus apex shows remodeling of the cricoid cartilage in the region of the cricoarytenoid joint (arrowheads). In (C), a non–contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image. In (D), a contrast-enhanced T1W fat-suppressed image shows the mass at the lower supraglottic region just above the pyriform sinus region to homogeneously enhance. In (E), a T2-weighted image shows internal characteristics consistent with schwannoma. F: Patient 2. Axial CT image showing an exophytic tumor with a low-attenuating periphery and enhancing inner part originating from the aryepiglottic fold. This turned out to be a schwannoma. (Courtesy Marie-Madeleine Plantet, Saint-Cloud, France.)

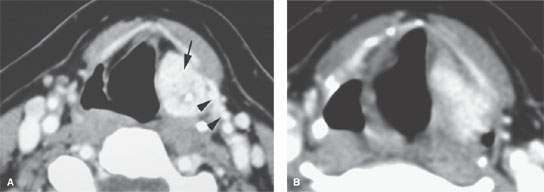

FIGURE 205.2. A patient presenting with a submucosal supraglottic mass and vocal cord dysfunction. A, B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows an excessively enhancing mass centered in the aryepiglottic fold (arrow). There is also a very prominent superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle (arrowheads) that identifies this as an arterialized lesion, subsequently shown to be a paraganglioma.

FIGURE 205.3. A–C: A patient presenting with a submucosal mass of the aryepiglottic fold. Based on the images alone, the differential diagnosis favored a benign tumor, possibly a salivary gland malignancy, neurogenic tumor, or perhaps sarcoma. However, clinically, the mass showed characteristics suggestive of a slow-flow vascular malformation. That diagnosis was confirmed by minimal biopsy, with deep biopsies being avoided. That distinction could not have been made on the basis of this imaging examination.

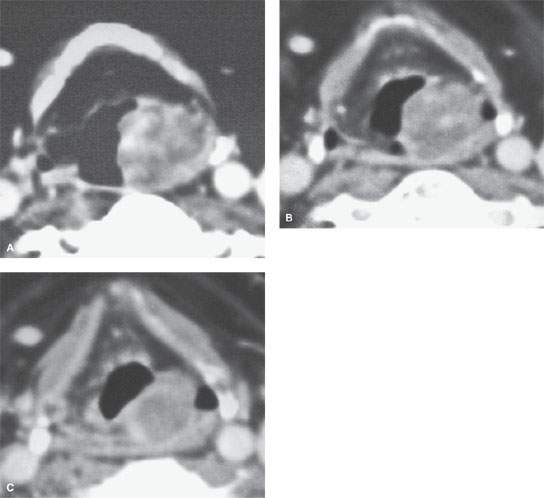

FIGURE 205.4. A–C: Computed tomography (CT) of a patient with papillomatosis of the upper and lower airway. In (A), the polyps thicken the mucosa (arrows) and weaken the airway by growing into its cartilaginous and membranous walls. In (B), CT allows for a survey of the entire airway and can obviate endoscopy and bronchoscopy in some patients. In (C), a high-resolution CT image of the chest (lung window) reveals bilateral cavitating lung nodules. D, E: Contrast-enhanced CT of a patient with fibrovascular reactive polyps in the larynx, originally thought to be neoplastic or possibly a hemangioma.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Recurrent Respiratory Papillomas and Other Papillomas of the Larynx

Etiology

Papillomas of the larynx are the most common benign tumors encountered in the larynx and trachea. They occur elsewhere in the upper respiratory system as well. They typically do not come to diagnostic imaging. Papillomas of the larynx are caused by the human papillomavirus; the virus and disease most commonly starts in childhood but may persist into or start in adulthood (Fig. 205.4A–C).

Sporadic papillomas occur in adults (Fig. 205.4D,E).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Recurrent respiratory papilloma (RRP) and other papillomas are relatively uncommon and have no particular gender predilection. The sporadic papillomas are usually nonviral in origin and likely linked to smoking.

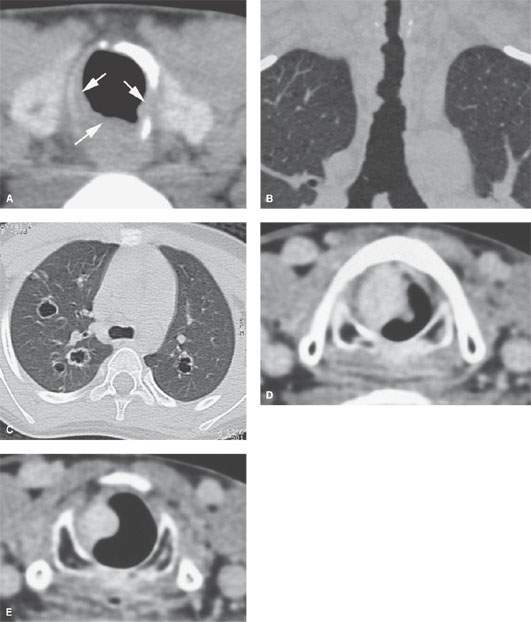

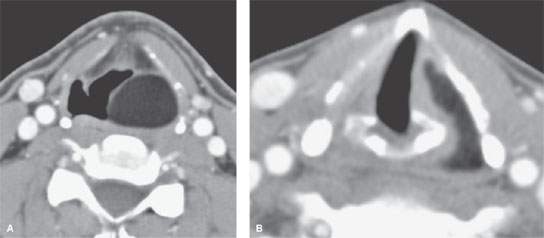

FIGURE 205.5. Axial computed tomography images through the larynx show a well-demarcated, homogeneously fat density mass in the left aryepiglottic fold (A) extending into the paraglottic space and pyriform recess apex (B). (Lipoma courtesy Frank Pameijer, Utrecht, The Netherlands.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree