LATERAL COMPARTMENT: NONNODAL MASSES

KEY POINTS

- Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography provide the critical and usually definitive data needed in the diagnosis and management of lateral compartment masses.

- Prompt and accurate imaging can help to avoid potentially severe complications in some lateral compartment pathology.

- Imaging-guided tissue sampling may be useful in the management of these masses.

INTRODUCTION

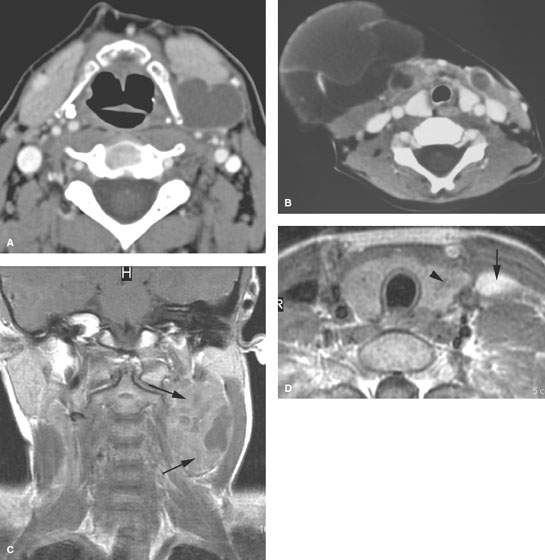

The lateral compartment of the neck is discussed in this chapter as the site of origin of nonnodal mass lesions of the infrahyoid neck. Nodal masses are discussed in Chapters 157 through 159. The lateral compartment is commonly secondarily involved by masses that originate in the visceral compartment, posterior compartment, and contiguous retropharyngeal space; this is discussed in Chapters 150, 161, and 162. The lateral compartment may also be secondarily involved with inflammatory conditions, such as suppurative adenitis, thrombophlebitis, arteritis, and the less common deep neck abscess, which occasionally mimic other masses; these are discussed in Chapter 155. Other sources of masses include acquired vascular conditions, discussed in Chapter 154, and developmental branchial abnormalities, discussed in Chapter 153 (Fig. 156.1). The spectrum of disease that might present as a mass and that arises in the lateral compartment is outlined in Table 156.1.

Clinical Presentation

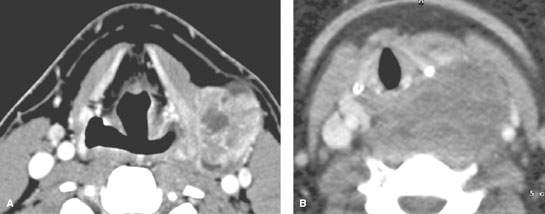

The primary presentation may be that of a neck mass of uncertain etiology without associated signs, symptoms, or other physical findings. There may be associated pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, or dysphonia (Fig. 156.2). Airway compression is possible. There is often a history of progressive enlargement of the mass.

Tenderness, fever, and associated generalized swelling may be present and are much more likely in the inflammatory conditions discussed in Chapter 155. Vascular malformations may be compressible and/or pulsatile, and masses may feel obviously cystic to palpation (Chapter 154).

Neurologic dysfunction may be due to involvement of the cervical sympathetics, vagus nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and phrenic nerve. Signs of cervical spinal cord compromise or rapid enlargement, when present, suggest that a very urgent problem might be at hand.

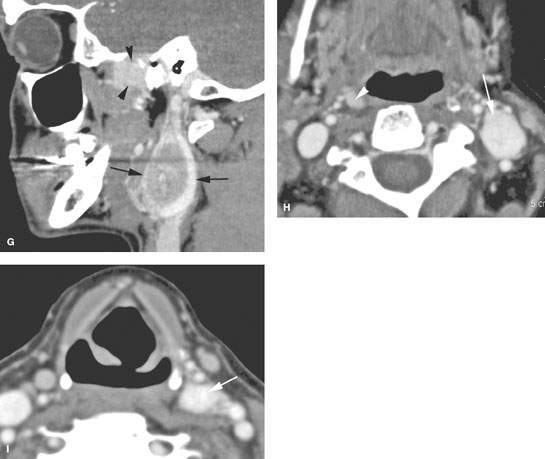

FIGURE 156.1. Three patients presenting with lateral neck masses. A: Patient 1, an adult with a lateral compartment mass due to a second branchial cleft cyst as seen on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). B: Pediatric Patient 2, presenting with a venolymphatic malformation as an explanation for the right lateral neck mass. Its insinuating growth pattern and involvement of the opposite side as well as morphology, as seen on contrast-enhanced CT, suggest the correct diagnosis. C, D: Magnetic resonance study of Patient 3 presenting with a lateral neck mass due to a thymoma arising in ectopic thymus tissue as seen in a contrast-enhanced T1-weighted coronal image. In (D), ectopic thymic tissue in the lateral compartment (arrow) and also within the thyroid gland (arrowhead) is shown.

APPLIED ANATOMY

The anatomy of interest is discussed in detail in Chapter 149 and summarized in Chapter 150 with regard to its application in evaluating neck masses.

The anatomy of the lateral compartment is essentially that of the carotid sheath and its relationship to the anterior and posterior triangles, the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the core visceral and posterior compartments. All of these elements, together with knowledge of neck development, predict the possible source of a nonnodal mass. The relationship of the lateral compartment to the retropharyngeal space medially and the thoracic inlet and suprahyoid neck space must be understood. Essentially, there is relatively free communication within the lateral compartment between the anterior and posterior triangles and the retropharyngeal space. The relationship of those spaces to the superficial fascia (platysma) and investing and prevertebral layers of the cervical fascia should be reviewed, if necessary, in Chapter 149.

TABLE 156.1. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF NONNODAL LATERAL COMPARTMENT NECK MASSESA

FIGURE 156.2. Two patients with masses that might have arisen in either the visceral or retropharyngeal compartment or lateral compartment. A: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) in Patient 1 showing a synovial cell sarcoma that probably has arisen from the lateral wall of the hypopharynx. B: Contrast-enhanced CT study in Patient 2 with a sarcoma that may have arisen either in the lateral neck or retropharyngeal space, showing the continuity between these two spaces.

Structures of Interest

The analysis of a nonnodal mass of the lateral compartment depends on a thorough understanding of its relationship to the carotid sheath and the following boundaries:

- Superiorly: Hyoid bone as the arbitrary boundary

- Inferiorly: Thoracic inlet

- Anteriorly: Anterior triangle

- Posteriorly: Posterior triangle

- Medially: Visceral compartment, retropharyngeal space, and posterior compartment

- Laterally: Sternocleidomastoid muscle and/or the superficial fascia and subcutaneous fat

IMAGING APPROACH

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The infrahyoid neck is mainly evaluated with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The specifics and relative value of using these studies in this anatomic region are reviewed in Chapter 149. Problem-driven protocols for CT and MRI are presented in Appendixes A and B. MRI is preferable when the known or suspected diagnosis is a venolymphatic malformation or if there is neurologic compromise.

Other

Ultrasound has a potential triage role to play in the evaluation of a pulsatile mass but is most often cost additive and unlikely to contribute to definitive medical decision making (Fig. 156.3). It may actually delay a more timely use of a likely more definitive CT or magnetic resonance (MR) study.

Catheter angiography is used very selectively and most often as a prelude to endovascular intervention once the diagnosis has been established by imaging and related computed tomographic angiography or MR angiography.

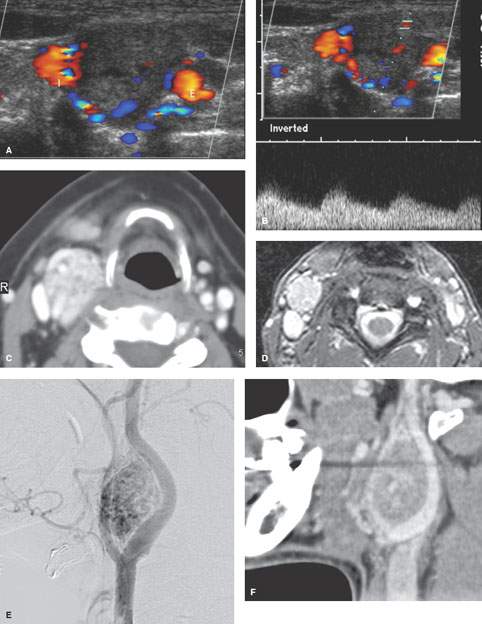

FIGURE 156.3. Four patients with various paragangliomas presenting as lateral compartment masses. A–C: Patient 1. In (A) and (B), carotid ultrasound shows a fairly typical appearance of the highly vascular carotid body tumor at the carotid bifurcation. In (C), contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) shows the carotid body tumor at the carotid bifurcation. D, E: Carotid body tumor presenting as a lateral neck mass in Patient 2 with arm numbness. The etiology of the mass is fairly apparent from the poor-quality magnetic resonance image (D) study; however, an angiogram (E) was done, confirming the diagnosis. F, G: Patient 3 presenting with a pulsatile neck mass due to a carotid body tumor. In (F), the CT angiogram is fairly definitive for the diagnosis based on appearance and location. A second very rare paraganglioma (G) was seen adjacent to the foramen ovale (arrowheads) in addition to the one at the carotid bifurcation (arrows). H, I: Patient 4 presenting with a left neck mass as seen on contrast-enhanced CT (arrows), which is shown to be a carotid body tumor. The appearance and location are fairly typical; however, the diagnosis was further confirmed by recognizing a small glomus vagale type of paraganglioma (arrowhead in H) on the right and a third paraganglioma in the lateral compartment of the mid neck (arrow in I) growing along the superior laryngeal neurovascular bundle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree