LEUKEMIA AND PLASMA CELL NEOPLASMS

KEY POINTS

- Plasma cell tumors and leukemia may present as primarily intramedullary and extramedullary processes in the head and neck.

- Plasma cell tumors may not be systemic at the time of head and neck presentation.

- Intramedullary disease may mimic skull base osteomyelitis or metastasis.

- Extramedullary disease may mimic other localized mass lesions, both benign and malignant.

- Intracranial manifestations may be a pachymeningeal and/or leptomeningeal process.

PLASMA CELL TUMORS

Clinical Perspective and Pathology

There is a considerable male preponderance in plasma cell dyscrasias, and the disease generally presents after the age of 40 years.1–3.

Plasma cell tumors of the head and neck present in four main ways, including: (a) solitary plasmacytoma of bone (Fig. 28.1); (b) primary plasmacytoma of soft tissues, also called extramedullary plasmacytoma (Fig. 28.2); or as a manifestation of systemic disease, either (c) multiple myeloma, or (d) plasma cell leukemia, sometimes called myelomatosis4,5 (Fig. 28.3).4,5

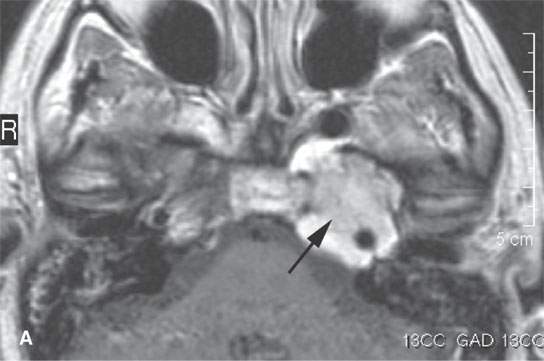

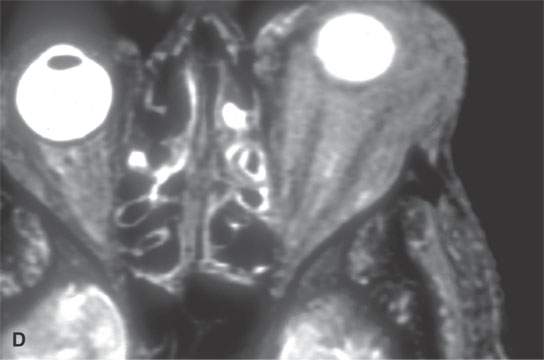

FIGURE 28.1. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CEMR) in a patient with solitary plasmacytoma of the petrous apex. A: T1-weighted (T1W) image showing the enhancing petrous apex mass (arrows). B: T2-weighted (T2W) image showing the petrous apex mass to be isointense with brain (arrows).CEMR of a patient with a solitary plasmacytoma centered in the masticator space. C: Contrast-enhanced T1W image showing the enhancing, infiltrating tumor within the masticator space involving the mandible (arrows). dD: T2W image showing the mass to be slightly inhomogeneous (arrows).

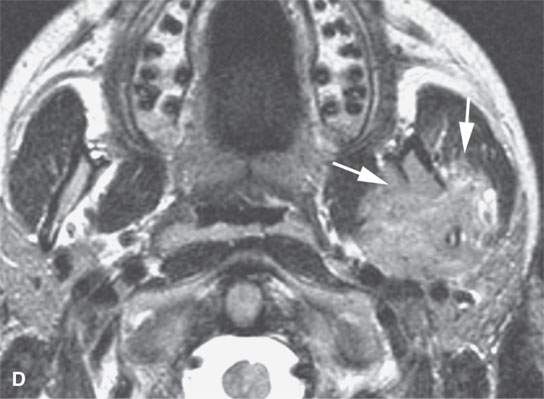

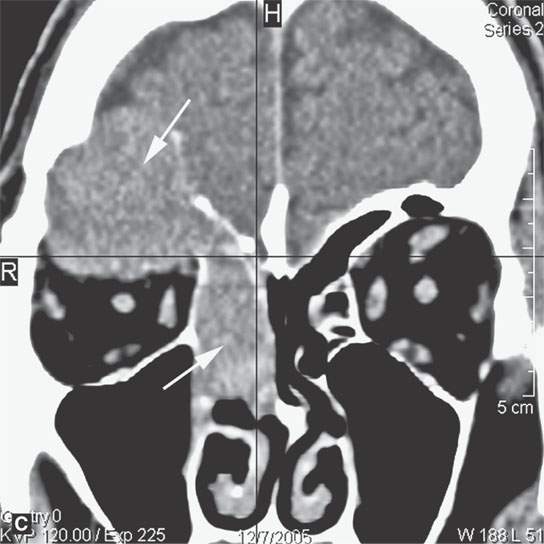

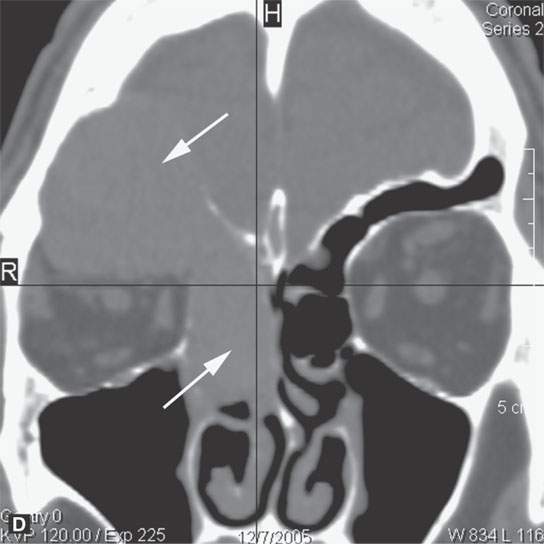

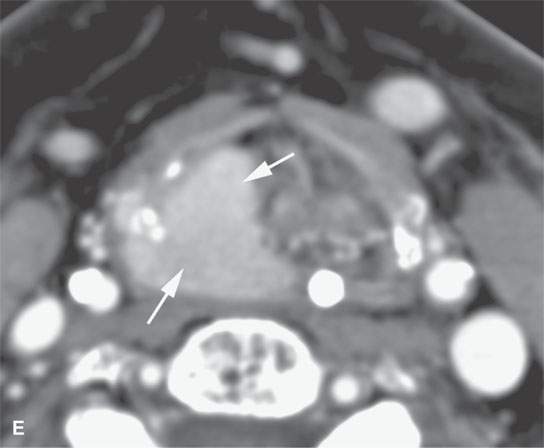

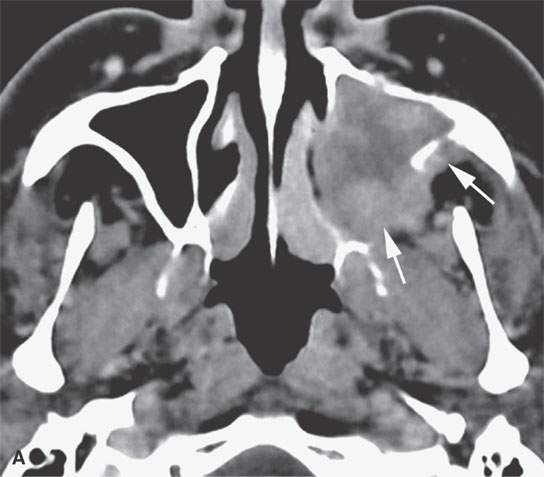

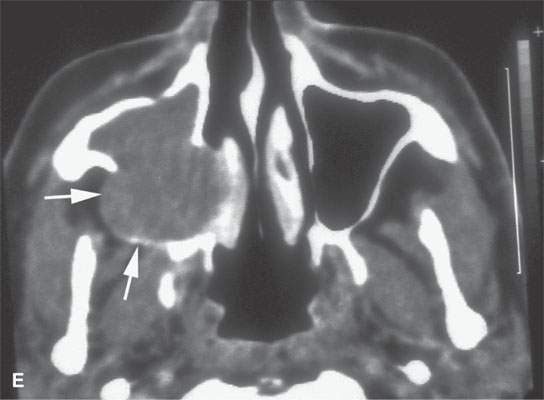

FIGURE 28.2. Three patients with extramedullary plasmacytomas. A: Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the first patient with extramedullary plasmacytoma of the nasopharynx (arrows). B: Bone erosion along the posterior and lateral skull base (arrows). C: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of a second patient with extramedullary plasmacytoma arising in the frontal sinus (arrows). D: Bone windows of the same patient seen in (C). E: CECT of third patient with extramedullary plasmacytoma of the larynx (arrows).

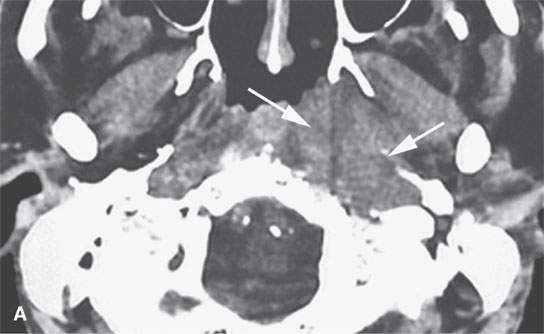

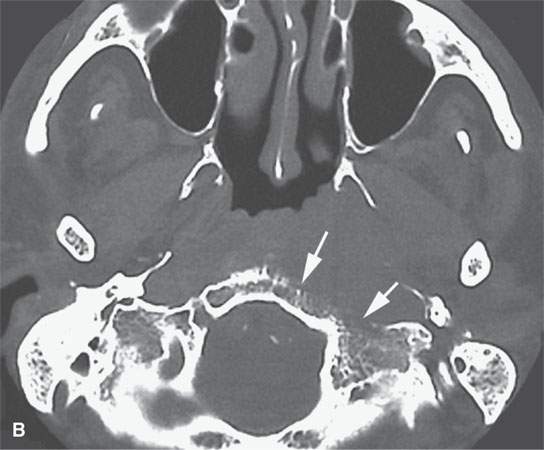

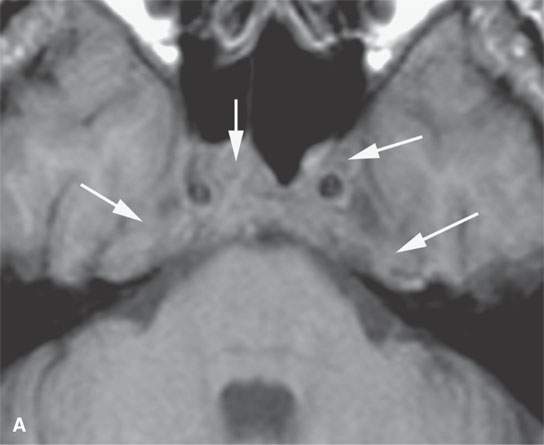

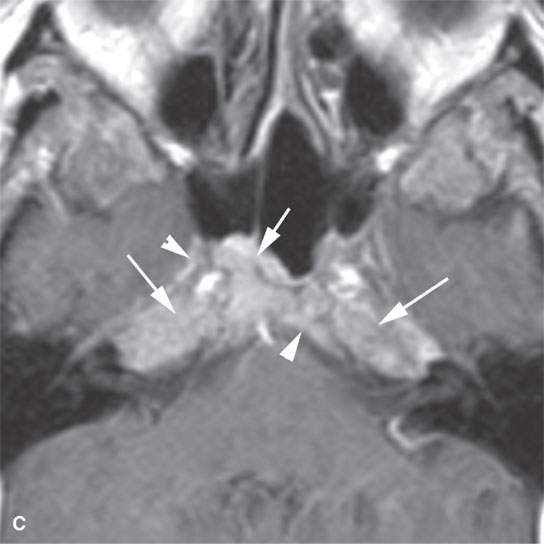

FIGURE 28.3. A patient with multiple myeloma involving the central skull base. A: Non–contrast-enhancedT1-weighted (T1W) image showing the infiltration of the normally fatty marrow at the skull base (arrows). B: T2-weighted image showing the infiltrating tumor to be about the same signal intensity as brain. C: T1W contrast-enhanced image showing diffuse enhancement of the infiltrating tumor (arrows) and related dural enhancement (arrowheadss).

Most extramedullary plasmacytomas occur in the head and neck. The entire upper respiratory tract is at risk, but the sinonasal region (Fig. 28.2C,D), nasopharynx (Fig. 28.2A,B), and tonsils are preferred sites. The larynx (Fig. 28.2E), oropharynx, and floor of the mouth and palate are also sites of origin. Salivary gland, tracheal, middle ear, and thyroid involvement is very unusual. Plasma cell masses in these regions are generally solitary but can be multiple. When the cranial vault, skull base, or facial bone involvement is present, it usually is associated with disseminated varieties of the disease; however, it can still be a localized form of the diseased as discussed subsequently (Fig. 28.1). Extramedullary plasmacytoma will go on to more disseminated disease in up to one third of patients within several years.

Localized disease is treated by surgery, radiation, or combined therapy and disseminated disease with chemotherapy.5,6 Prognosis in disseminated disease is guarded. Local disease is curable, but the patients must be followed carefully because of the high risk of recurrent multifocal or disseminated disease.

Imaging Appearance

Localized lesions tend to be round, lobulated, and invading both bone and soft tissue (Figs. 28.1 and 28.2). They often have a rich capillary stroma; thus, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CEMR) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) typically show an enhancing mass (Figs. 28.1 and 28.2C,D). The appearance on T2-weighted images is typical of other cellular tumors7,8 (Fig. 28.1).7,8 The fatty marrow of involved bones will be obliterated by the invading plasma cells on T1-weighted non–fat-suppressed images, and CEMR may obscure this finding since the tumor can enhance and become isointense with surrounding, at least normally partially fatty, marrow (Fig. 28.3).

A solitary plasmacytoma can occur in any part of the face, skull, or cervical spine. Apparently, initial solitary bone lesions called solitary plasmacytoma of bone will go on to more disseminated disease in about one third to one half of patients within several years. Growth into the soft tissues from bone is common (Fig. 28.1C,D). The bone usually has a “bubbly” expanded appearance (Fig. 28.2C,D). The remaining computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance is the same as extramedullary tumors. The differential diagnosis of bone-centered lesions is usually between plasmacytoma, giant cell tumor, dental origin neoplasm, and metastasis depending on the site involved.

Disseminated disease will manifest itself as either multiple discreet bony lesions of multiple myeloma or diffuse marrow space infiltration (Fig. 28.3). These patterns are recognized by typical multiple osteolytic bony lesions that originate in the marrow space of involved bones and then extend to involve the surrounding cortical surfaces in the case of multiple myeloma. This may progress to a more disseminated “moth-eaten” bone pattern typical of more aggressive neoplasms. The marrow space involvement is manifest by the replacement of the normally partially fatty signal of the marrow space with tissue density or signal intensity. When this enhances on CEMR, the involvement of the marrow space will become less conspicuous on T1-weighted images that are not fat suppressed.

Adjacent dura will enhance, and spread to soft tissues beyond the bony margins is possible (Fig. 28.3C). MRI is far more sensitive than CT for the detection of such meningeal involvement and/or reactive changes. Dural disease is most often a reflection of adjacent bone involvement (Fig. 28.3). The bone pattern involvement with plasma cell dyscrasias can overlap with that seen in metastases, skull base osteomyelitis, and leukemia; those bone patterns seen with leukemia are discussed in the next section of this chapter.

LEUKEMIA

Clinical Perspective and Pathology

This group of acute and chronic diseases is one that arises within myeloid elements of the hematopoietic system. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is classified with the lymphomas. Myeloid leukemia is essentially a disease of the bone marrow, and its principle manifestation is in that “organ system” and the peripheral blood.9,10 This disease occurs in all age groups, with specific tendencies depending on the exact type of leukemia encountered.

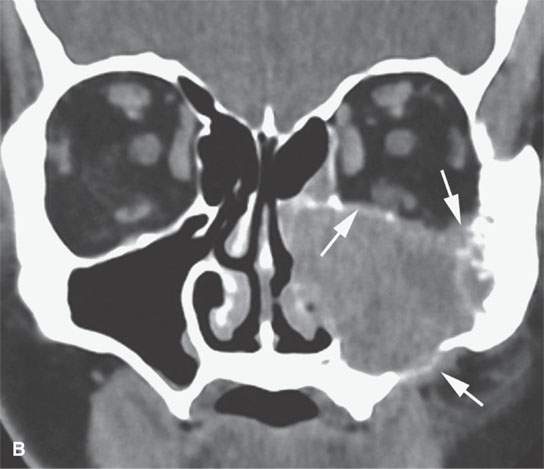

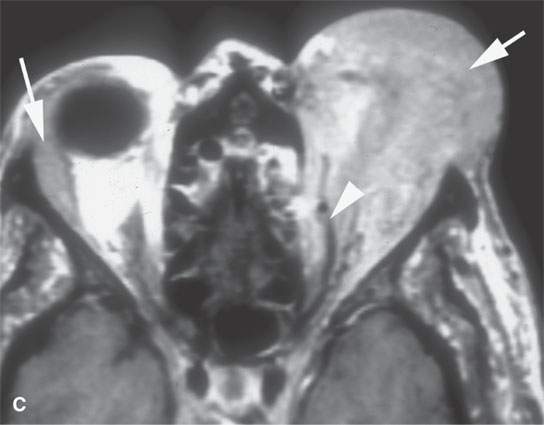

The tendency for greater or lesser degrees of extramedullary disease varies somewhat with the type of leukemia. Extramedullary localized tumor cell collections as a manifestation of myeloid leukemias are most properly called granulocytic sarcomas (Fig. 28.4). The old term chloroma should be abandoned. Other terms used include extramedullary myeloblastic tumor, myelosarcoma, myeloblastoma, and myeloid sarcoma in the myeloid leukemias.

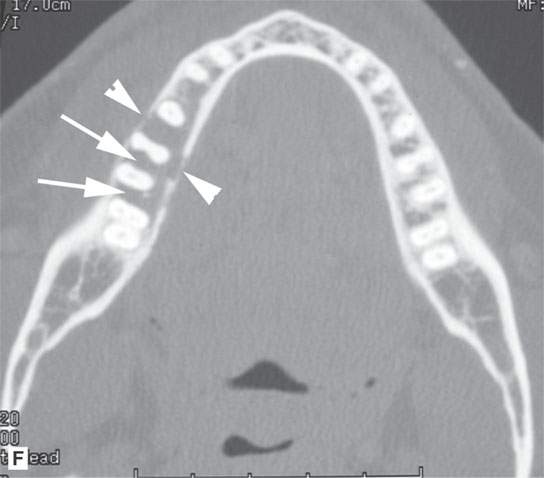

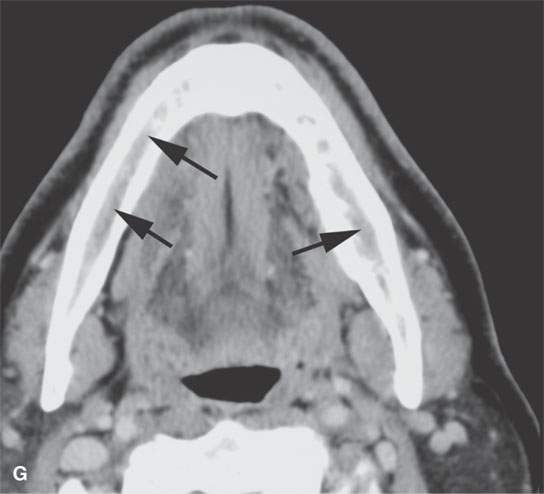

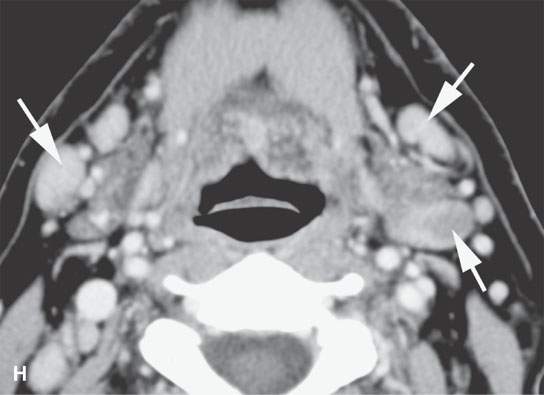

FIGURE 28.4. Four patients with localized manifestations of leukemia. A, B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of a patient with granulocytic sarcoma of the left maxillary sinus that destroys bone and infiltrates the fat pad posterior to the maxillary sinus (arrows). B: Infiltration along the superior wall of the maxillary sinus into the orbit and the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus is present (arrows). C, D: A patient with bilateral granulocytic sarcomas of the orbit. Changes are much more prominent on the left compared to the right.The contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image (C) shows infiltrating masses on both sides (arrows) and an enlarged orbital vein (arrow) on the left.The T2-weighted image (D) shows the process to be less intense than brain. E: CECT of a patient with granulocytic sarcoma right maxillary sinus producing an expanded experience (arrows) of the sinus mimicking mucocele. F–H: Computed tomography study of a patient with leukemic infiltration of the mandible presenting with loose teeth and gingival soreness. F: The bone window shows erosion of the buccal and lingual cortex (arrowheads) and infiltration of the narrow space (arrows) between the affected teeth. G: The soft tissue windows show infiltration of the normally fatty marrow space (arrows). H: CECT showing enlarged lymph nodes (arrows) related to the leukemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree