Intestinal endometriosis occurs in 4% to 37% of women with deep endometriosis (DE). Noninvasive diagnosis of presence and characteristics of rectosigmoid endometriosis permits the best counseling of patients and ensures best therapeutic planning. Magnetic resonance enema (MR-e) is accurate in diagnosing DE. After colon cleansing, rectal distention and opacification improves the performance of MR-e in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis. MR imaging cannot optimally assess the depth of penetration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall. There is a need for multicentric studies with a larger sample size to evaluate reproducibility of MR-e in diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis for less experienced radiologists.

Key points

- •

Several studies showed the accuracy of MR-enema (MR-e) in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis.

- •

During MR imaging, rectosigmoid opacification with ultrasound gel helps to delineate the intestinal wall, distinguishing it from the surrounding structures, and to identify intestinal endometriotic lesions.

- •

Despite intestinal distention and opacification, MR-e does not allow to distinguish the various layers of the intestinal wall in the normal colon (serosa, muscularis propria and mucosa).

Introduction

Endometriosis is a gynecologic condition characterized by the presence of endometriotic glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity. It affects at least 3.6% of reproductive age women and it usually causes pain (dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, dyschezia), infertility, and other symptoms, depending on the location of the lesions, such as urinary complaints in patients with bladder endometriosis and intestinal complaints in patients with bowel endometriosis. Endometriosis is usually classified in ovarian endometriosis, superficial endometriosis, and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DE). Ovarian endometriosis includes superficial ovarian implants and ovarian endometriotic cysts. Superficial endometriosis (also known as peritoneal endometriosis) is characterized by peritoneal infiltration of less than 5 mm depth. DE is the most severe form of the disease and is histologically defined as endometriosis infiltrating the retroperitoneum or the wall of pelvic organs by at least 5 mm. DE may affect various pelvic organs and spaces including the posterior border of the cervix and isthmus of the uterus, uterosacral ligaments, paracervix, rectosigmoid, pouch of Douglas, bladder, vagina, and pelvic peritoneum.

Intestinal endometriosis is the most challenging form of endometriosis for the gynecologist. It occurs in 4% to 37% of women with DE. The rectosigmoid colon is the most frequent location (about 85% of the cases), followed by the ileum, appendix, and cecum. The nonsurgical diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis is necessary to offer the best treatment planning for the patients. Hormonal therapies have been shown to be effective in improving not only pain but also intestinal symptoms of patients with rectosigmoid endometriosis. Surgery is required in patients with subocclusive symptoms, in those with contraindications to hormonal therapies or refusing these treatments, in those with symptoms persisting despite the use of hormonal therapies, and in those desiring to get pregnant, because all the available treatments are contraceptive or do not allow to conceive. At laparoscopy, rectosigmoid endometriosis can be treated by nodulectomy, full-thickness disc resection, and segmental bowel resection. In patients undergoing surgery, it is important not only to establish the presence of rectosigmoid endometriosis but also to define the characteristics of the endometriotic nodules, such as the longitudinal diameter of the largest one, the depth of infiltration in the intestinal wall, the distance between the more caudal nodule and the anal verge, the presence of multifocal disease (presence of multiple lesions affecting the same segment), and the infiltration of adjacent organs.

Overview of the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis

The presence of rectosigmoid endometriosis should be suspected when the typical endometriosis-related pain symptoms are associated with intestinal complains, such as abdominal bloating, intestinal cramping, painful bowel movements, constipation, and diarrhea (which often worsen during the menstrual cycle), and passage of mucus and rectal bleeding during the menstrual cycle. These intestinal symptoms are very common, and, in particular, they are similar to those of irritable bowel syndrome. The clinical examination (digital vaginal and rectal examination) may allow to detect a thickening or a nodule in the posterior vaginal fornix and rectum, which are suggestive of DE. However, the physical examination does not allow a definitive diagnosis and it cannot detect endometriotic nodules located above the rectum. Therefore, imaging techniques are required for the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis.

Abdominal ultrasound has no role in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis; however, it can be useful to exclude hydronephrosis caused by ureteral stenosis owing to endometriosis. Several studies showed the accuracy of transrectal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis but this examination is rarely used because of the discomfort caused by the procedure. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVS) is currently the first-line investigation for the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis. A recent systematic review and metanalysis including 10 studies (2639 patients) showed that TVS has a sensibility of 91% and a specificity of 97% in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis. TVS has the advantage of being performed by gynecologists, which tend to have an expertise in treating patients with endometriosis, it is cheap and does not require bowel preparation. However, TVS cannot detect nodules located proximally to the sigmoid because they are beyond the scope of this investigation. Furthermore, the diagnostic performance of TVS depends on the experience of the ultrasonographer. Improvement in the diagnostic accuracy of TVS may be obtained by introducing saline solution or gel in the vagina and/or rectum (“enhanced” or “modified” TVS), as their distention may enhance the visualization of DE nodules.

Endoscopic ultrasonography has been widely used to diagnose rectosigmoid endometriosis. This examination is particularly precise in estimating depth of infiltration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall, size and location of the nodules, and distance between the nodule and the anal verge. Endoscopic ultrasonography and MR imaging have similar diagnostic performance in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis ; however, the first is more precise than MR imaging in identifying the infiltration of the submucosa and mucosa.

Double contrast barium enema (DCBE) has been widely used for the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis. This examination is easy to be performed and cheap, but its use in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis has some limitations: conventional radiology requires administration of ionizing radiation to women of reproductive age; DCBE requires an experienced radiologist, mainly in patients with suspicion of intestinal endometriosis; DCBE does not allow estimation of the depth of infiltration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall or the differentiation of bowel endometriosis from other intestinal pathologies, and, lastly, it does not identify the infiltration of adjacent organs.

Multidetector computerized tomography enema (MDCT-e) has a sensitivity of 98.7% and a specificity of 100% in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis. This examination has the advantage of identifying small endometriotic lesions located on the serosal surface, it may identify nodules located on the cecum and last ileal loops, and it precisely estimates the degree of infiltration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall. Currently, new systems of dose control assist the radiologist in optimizing and decreasing the administered radiographic dose; for this reason, ionizing radiation is a minor limitation of MDCT when used to examine women of childbearing age.

However, the disadvantage of using iodinated contrast medium and exposing patients to radiation are 2 shortcomings of CT underlined many times in the literature. Furthermore, a recent study showed that MDCT-e and magnetic resonance enema (MR-e) have similar diagnostic performance in identifying rectosigmoid endometriosis.

Virtual colonoscopy (CTC) has recently been used for the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis. However, it not only requires bowel preparation, and the use of iodinated contrast medium during CTC is still controversial. A recent study showed that CTC and TVS have similar diagnostic performance in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis; however, CTC is more panoramic and more precise in estimating the distance between the endometriotic nodules and the anal verge ; this parameter is particularly relevant for surgeons because patients with low rectal nodules tend to have an increased risk of ileostomy or colostomy at the time of surgery.

MR imaging in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis

MR imaging has long been considered the first-line investigation of the diagnosis of DE, including rectosigmoid endometriosis. MR imaging should be performed on a 1 to 1.5 T magnet using at least an 8-channel pelvic phased array coil. The standard examination protocol includes the following sequences: T2-weighted fast relaxation fast spin echo (T2W FrFSE) axial images, T2W FrFSE fat sat coronal images, FIESTA (or similar) sequence in coronal plane, T2W FrSE sagittal images, T2W FrFSE fat sat sagittal images, and diffusion-weighted echo planar imaging (b = 1000, 1500) axial images. T1-weighted images are acquired using fat-suppression even after contrast enhancement (gadobutrol at a dosage of 0.2 mmol/kg body weight). This sequence allows differentiating between hemorrhagic and fatty content of adnexal cysts. It is important to use an adequate field of view and a slice thickness of about 3 to 4 mm, particularly in case of nodules with main diameter of approximately 10 mm.

Diffusion-weighted imaging

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is now clinically accepted to detect and characterize focal lesions, to differentiate between malignant and benign lesions, and to monitor treatment response. However, the usefulness of DWI for differentiating benign from malignant ovarian cystic lesions is controversial, because teratomas and endometriomas tend also to have restricted diffusion. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values has been used to identify endometriomas from hemorrhagic cysts, and these values may represent an additional diagnostic tool to differentiate them. However, as there was some overlap between the ADC values of endometriomas and hemorrhagic cysts, such diagnosis should be based on a combination of clinical history and conventional MR imaging with DWI findings, rather than based on DWI alone. To the best of our knowledge, there is no attempt of DWI clinical use in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis; in our experience these sequences have no relevant role in the diagnosis of DE.

Concerning the use of paramagnetic contrast medium injection, whereas some authors obtain images before and after contrast, other authors do not use contrast-enhanced imaging owing to the lack of a definite consensus on its usefulness. In fact, an accurate preoperative assessment of endometriosis extension, including deep implants and adhesions, has been demonstrated even without the use of gadolinium contrast medium.

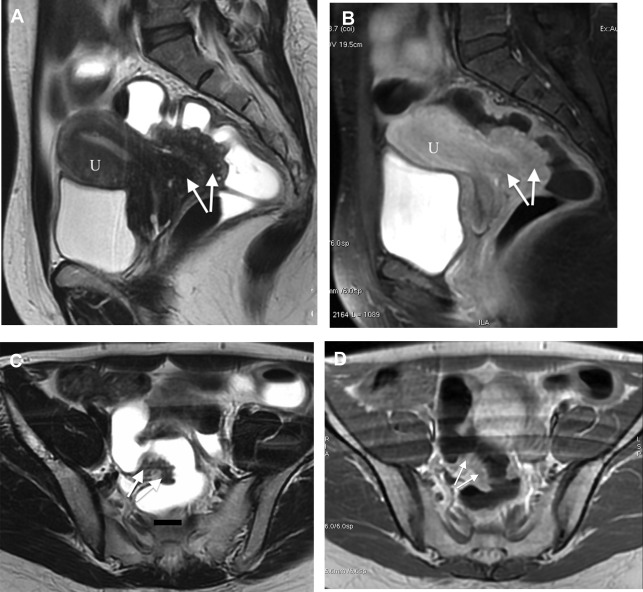

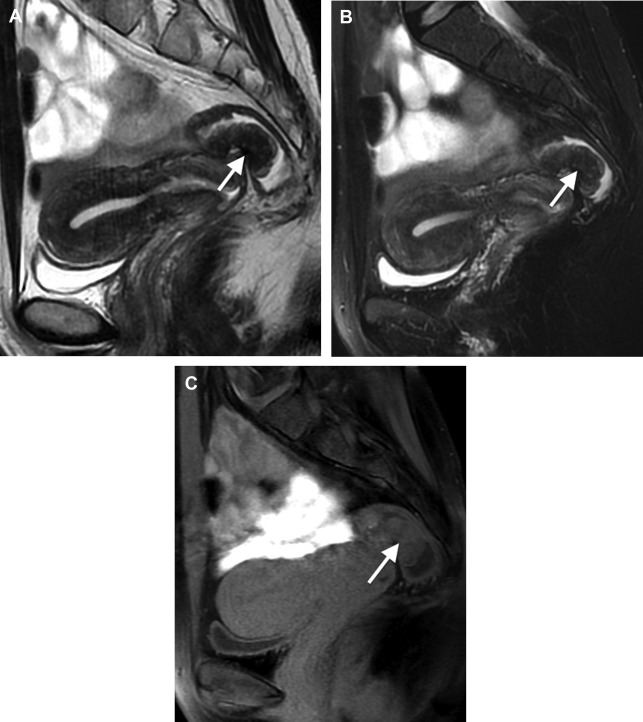

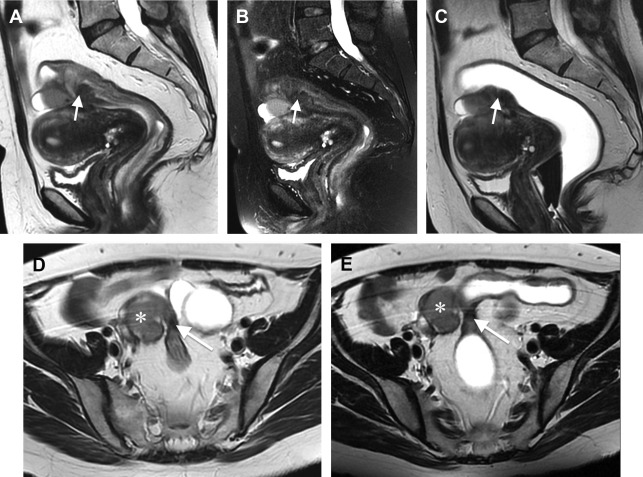

Rectosigmoid endometriosis usually contains extensive fibrosis and smooth muscle cells, with little or no endometriotic tissue ( Fig. 1 ). Therefore, DE usually has very similar signal intensity to that of the surrounding fibromuscular structures. Rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules appear as solid nodular thickening in the rectosigmoid wall; the lesion usually joins the intestinal wall at an obtuse angle and may have a stellar outline. The endometriotic nodule has a signal similar to that of the muscles in T1- and T2-weighted images. Its penetration in the intestinal wall with the subsequent disappearance of the fatty plan between the intestine and the nodule is the main parameter to diagnose infiltration of the muscularis propria. Mucosal involvement is rare; it may appear as a bulging transmural mass. Endometriotic foci appear sometime as spots of high signal intensity on T2- and T1-weighted images ( Figs. 2 and 3 ).

The radiological report should describe number and location of the nodules, degree of infiltration of endometriosis in the intestinal wall, maximum diameter of the nodules, distance between the lower border of the endometriotic nodule and the anal verge, and the presence of infiltration of adjacent organs (such as the vagina).

In 2004, a historical study by Bazot and colleagues including 195 patients demonstrated that MR imaging with gadolinium contrast-enhanced sequences has high accuracy in diagnosing DE. In this study, MR imaging had an accuracy of 94.9% for diagnosing rectosigmoid involvement, a sensitivity of 88%, a specificity of 97.8%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 95%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 95%. A recent systematic review and metanalysis including 6 studies (424 patients, of whom 190 had rectosigmoid endometriosis) showed that MR imaging has a sensibility of 85%, a specificity of 96%, a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 20.4, and a negative likelihood ratio (LR−) of 0.16 in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis. The major limitation of this metanalysis was that the prevalence of DE in the studies ranged from 6% to 76%, thus representing a significant heterogeneity. Another recent systematic review and metanalysis on 8 studies (1132 patients) confirmed the diagnostic performance of MR imaging in diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis, reporting a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity of 96%, an LR+ of 17.26, and LR− of 0.15.

3T MR imaging guarantees high spatial and contrast resolution. Its use has been studied in the diagnosis of DE. In a prospective study, 46 women underwent a 3.0 T MR imaging examination with the following protocol: T2-weighted FrFSE HR sequences, T2-weighted FrFSE HR CUBE 3D sequences, T1-weighted FSE sequences, LAVA-flex sequences. The sensibility in diagnosing endometriosis was 96.97%, the specificity was 100.00%, the PPV was 100.00%, and the NPV was 92.86%. A more recent retrospective study including 37 women investigated the diagnostic performance of 3.0 T MR imaging without intestinal hypotonization and rectal opacification in the diagnosis of DE. The authors reported a sensitivity of 94.4%, a specificity of 94.7%, PPV of 94.4%, and NPV of 95.0% for diagnosing rectosigmoid endometriosis.

MR imaging enema technique

DE can be difficult to distinguish from the surrounding structures because of its fibrous content. Given this background, rectosigmoid opacification with ultrasound gel can help to delineate the intestinal wall and to identify intestinal endometriotic nodules ( Figs. 4–6 ). The retrograde distention is performed after the patient lies on the MR imaging bed. It is usually performed on the lateral decubitus and then on the supine position. In claustrophobic patients, the prone decubitus may be used; it is also useful to reduce abdominal respiratory movements. The quantity of ultrasonographic gel used to distend the rectosigmoid varies in different studies: from 300–400 mL to 150–200 mL. A bowel preparation is usually performed before MR-e. In fact, without cleansing the colon, rectosigmoid distention and opacification may be insufficient for diagnosing endometriotic nodules. To decrease the peristalsis and improve the quality of the images, the patients are requested to fast for at least 4 hours before examination. Some radiologists use an antiperistalsis agent at the beginning of the examination, whereas others do not use intestinal hypotonization because of the small quantity of intraluminal contrast medium. Rectosigmoid opacification is obtained by some authors using ultrasonographic gel and by other authors using ultrasonographic gel diluted with saline solution (1:8). The use of ultrasonographic gel allows to fill the rectosigmoid without causing over distention. In contrast, the identification of bowel wall retraction, a sign of the presence of rectosigmoid endometriosis, is facilitated by using it. Several authors do not routinely use paramagnetic contrast medium during MR-e in patients with suspicion of endometriosis. Rectosigmoid endometriotic lesions are fibro-muscular structures located within the normal intestinal muscularis propria. Because of these histologic characteristics, after contrast medium injection, endometriotic nodules often have a very similar enhancement to the normal intestinal wall ( Figs. 7 and 8 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree