Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become the standard imaging modality for activity-related groin pain. Lesions, including rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis injury and osteitis pubis, can be accurately identified and delineated in patients with clinical conditions termed athletic pubalgia, core injury, and sports hernia. A dedicated noncontrast athletic pubalgia MRI protocol is easy to implement and should be available at musculoskeletal MR imaging centers. This article will review pubic anatomy, imaging considerations, specific lesions, and common MRI findings encountered in the setting of musculoskeletal groin pain.

Key Points

- •

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an essential tool for accurately identifying the various lesions seen with athletic pubalgia and core injuries.

- •

A dedicated athletic pubalgia MRI protocol is a useful adjunct in delineation of injury extent and can help with appropriate subspecialist referral.

Introduction

Groin pain in athletes has long been a diagnostic and therapeutic conundrum for orthopedic surgeons, sports medicine physicians, and the entire training staff for athletic teams and departments. The groin region is commonly injured during activities involving rapid acceleration, twisting and lateral motion, and abrupt changes in direction at the body’s musculoskeletal core. Sports including soccer, American rules football, hockey, and baseball have been associated with particularly high rates of activity-induced groin pain, or athletic pubalgia. Up to 13% of soccer injuries involve the groin. In 1 series, 58% of soccer players had experienced a groin injury. But as the understanding of the specific musculoskeletal lesions associated with athletic pubalgia has grown, so has the incidence of its diagnosis across a diverse population with wide variations in age, activity level, and favored athletic endeavor.

The clinical assessment of athletic pubalgia remains challenging, as multiple possible pathologies may yield similar presentations and findings on physical examination. Patients often present with inguinal pain, which may radiate into the perineum or medial thigh. Patients can experience an insidious onset of symptoms or an acute injury, but an acute on chronic presentation seems most prevalent. Symptoms may persist for unnecessarily long periods before the correct diagnosis is made, hindering participation and causing delays in return to activity. Such sports-related injuries of the groin were often labeled sports hernias early on. This term may have developed as a consequence of the anatomic proximity of the superficial inguinal ring to the true location of injury, causing confounding symptoms not unlike those produced by true hernias. This term is a misnomer, however, as magentic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown that there is very infrequently a true hernia in this patient population. Athletic pubalgia is better, as it implies a more clinical diagnosis, but it still falls short in identifying a true musculoskeletal lesion, of which there are many. More recently, the term core injury has been used to broaden the spectrum of musculoskeletal lesions that should be considered. In a general sense, these terms imply a clinical syndrome in which groin pain does not originate from intrinsic pathology of the hip ( Fig. 1 ).

Over the past 5 years, MRI has taken a central role in the diagnosis of athletic pubalgia or core injury, and in many cases, referral to the most appropriate subspecialist. There has been a great focus on lesions involving the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis and adductor longus anterior to the pubic bone and pubic symphysis, but many other sites of injury can be encountered at MRI. This article reviews the basic anatomy of the musculoskeletal pubic region as well as specific lesions leading to clinical athletic pubalgia or core injury. A dedicated MRI protocol will be detailed, as well as patterns of MRI findings reproducibly seen at MRI in these patients. Common confounding and concomitant inuries will be briefly discussed, and the expected post-operative MRI appearance as well as commonly observed complications will be described.

Introduction

Groin pain in athletes has long been a diagnostic and therapeutic conundrum for orthopedic surgeons, sports medicine physicians, and the entire training staff for athletic teams and departments. The groin region is commonly injured during activities involving rapid acceleration, twisting and lateral motion, and abrupt changes in direction at the body’s musculoskeletal core. Sports including soccer, American rules football, hockey, and baseball have been associated with particularly high rates of activity-induced groin pain, or athletic pubalgia. Up to 13% of soccer injuries involve the groin. In 1 series, 58% of soccer players had experienced a groin injury. But as the understanding of the specific musculoskeletal lesions associated with athletic pubalgia has grown, so has the incidence of its diagnosis across a diverse population with wide variations in age, activity level, and favored athletic endeavor.

The clinical assessment of athletic pubalgia remains challenging, as multiple possible pathologies may yield similar presentations and findings on physical examination. Patients often present with inguinal pain, which may radiate into the perineum or medial thigh. Patients can experience an insidious onset of symptoms or an acute injury, but an acute on chronic presentation seems most prevalent. Symptoms may persist for unnecessarily long periods before the correct diagnosis is made, hindering participation and causing delays in return to activity. Such sports-related injuries of the groin were often labeled sports hernias early on. This term may have developed as a consequence of the anatomic proximity of the superficial inguinal ring to the true location of injury, causing confounding symptoms not unlike those produced by true hernias. This term is a misnomer, however, as magentic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown that there is very infrequently a true hernia in this patient population. Athletic pubalgia is better, as it implies a more clinical diagnosis, but it still falls short in identifying a true musculoskeletal lesion, of which there are many. More recently, the term core injury has been used to broaden the spectrum of musculoskeletal lesions that should be considered. In a general sense, these terms imply a clinical syndrome in which groin pain does not originate from intrinsic pathology of the hip ( Fig. 1 ).

Over the past 5 years, MRI has taken a central role in the diagnosis of athletic pubalgia or core injury, and in many cases, referral to the most appropriate subspecialist. There has been a great focus on lesions involving the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis and adductor longus anterior to the pubic bone and pubic symphysis, but many other sites of injury can be encountered at MRI. This article reviews the basic anatomy of the musculoskeletal pubic region as well as specific lesions leading to clinical athletic pubalgia or core injury. A dedicated MRI protocol will be detailed, as well as patterns of MRI findings reproducibly seen at MRI in these patients. Common confounding and concomitant inuries will be briefly discussed, and the expected post-operative MRI appearance as well as commonly observed complications will be described.

Anatomy

The pubic symphysis includes 2 pubic bones with an articular disc interposed between the medial articular surfaces, resulting in an amphiarthrodial joint. The pubic bone forms the anterior aspect of the overall innominate bone, and is composed of superior and inferior pubic rami and the pubic body, which is situated medially. The medial aspect of the pubic body is ovoid, and covered by a thin layer of hyaline cartilage. The intervening disc is composed of fibrocartilage, and along with transversely oriented subarticular osseous ridges and grooves, helps stabilize the joint by dispersing shear forces. The pubic crest forms the superior and anterior margin of the pubic body. The pubic tubercle, which is the attachment site for the caudal rectus abdominis and the inguinal ligament, is a bony excrescence at the inferolateral margin of the pubic crest.

Beyond the articular disc, the joint is stabilized by 4 ligaments and multiple tendon attachments. The arcuate and the superior, anterior, and posterior pubic ligaments encase the pubis, although the former 2 ligaments are more functionally important, particularly for resisting shear forces. The arcuate ligament lines the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis, intimate to the articular disc and the rectus abdominis/adductor longus aponeurosis. The superior pubic ligament courses between the pubic tubercles. The anterior pubic ligament is comprised of a deep bundle that blends with the articular disc, and a superficial bundle that merges with the aponeuroses of the rectus abdominis and external oblique muscles. The posterior pubic ligament is thin, and least clinically important. These ligaments are generally not easily identifiable with MRI, but the arcuate ligament in particular is often injured and likely plays a central role in athletic pubalgia lesions.

The pubic symphysis stabilizes the anterior pelvis, while still allowing a small degree of craniocaudal movement at the joint. The large ovoid surface of the joint distributes craniocaudal shear forces produced while ambulating. While primarily a stabilizer of the anterior pelvis, anatomy at the symphysis allows for laxity and diastasis during pregnancy and childbirth ( Fig. 2 ).

The pubic symphysis is also a focal point for multiple musculotendinous attachments, contributing to overall pelvic stabilization. Abdominal wall muscles attaching to this location include the rectus abdominis, internal and external obliques, and the transversus abdominis. The adductor compartment muscles in the medial thigh attaching to the pubis include the pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, and gracilis. These extensive muscular, tendinous and ligamentous attachments, and the biomechanical forces distributed in the region are the impetus for labeling the region as the musculoskeletal core.

Functionally, the rectus abdominis and adductor longus are critical for stability at the anterior pelvis. These paired muscles attach on a broad aponeurotic plate spanning the midline from the pubic tubercles to the anteroinferior pubic bodies. Medially, the rectus abdominis tendons merge with the anterior pubic ligament. Laterally, the caudal rectus abdominis lies just posteromedial to the superficial inguinal ring, and likely plays a role in reinforcing the wall of the posteromedial superficial inguinal canal. At the lateral margin of the pubis, the adductor longus, the most anterior muscle among the adductors, blends with the caudal rectus abdominis attachment. At the midline, the caudal rectus abdominis, adductor fibers, arcuate ligament, and anterior pubic periosteum form the previously mentioned aponeurotic plate, which represents a merging of the right and left aponeuroses already described ( Fig. 3 ).

During core rotation and extension, the rectus abdominis and adductor longus are relative antagonists. While the rectus elevates the anterior pelvis, the adductor longus depresses it. Injury of 1 of the components tends to cause abnormal biomechanical forces on the opposing muscles and tendons, leading to further injury at the aponeurosis and its tenoperiosteal attachments. This can lead to pelvic instability, and ultimately osteitis pubis, any of which can contribute to chronic pelvic pain in athletes. Continued activity in the setting of pelvic instability establishes a cycle of additional injury reflecting the altered biomechanics, which often leads to further and more extensive core injury.

Imaging protocol

A dedicated athletic pubalgia MRI protocol is the study of choice for a specific subset of young athletic patients with groin pain, particularly if the pathology is felt to be extrinsic to the hip. Imaging is generally performed in a supine position for patient comfort, and the bladder should be emptied just before image acquisition. Either 1.5 T or 3 T systems should provide high-quality imaging of the pubic region. Coil selection and positioning are generally more important imaging considerationa than field strength with late model MRI systems. A receiver coil should be positioned over midline, centered on the pubic symphysis. Ideally, the coil will allow for imaging over a large field of view from hip to hip and midthigh to midthigh. The authors have found that phased array torso coils generally allow for at least survey imaging of the hips and thighs as well as high-resolution imaging of the pubic symphysis region of the smaller field-of-view sequences.

Three large field-of-view sequences of the pelvis are first obtained using a body coil. A coronal T1-weighted sequence is useful for assessment of marrow abnormalities, including fracture, neoplasm, or infection. A coronal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequence is useful for both osseous and soft tissue pathology, as well as abnormal fluid, and allows for homogenous suppression of fat, despite relatively poor signal-to-noise ratio. An axial large field-of-view fast spin echo (FSE) T2-weighted fat-saturated sequence allows for adequate contrast and coverage to identify marrow edema, bursitis, hip flexor injury, and even visceral pelvic lesions, as well as high enough resolution to delineate rectus abdominis injury.

Following large field-of-view sequences, higher-resolution sequences dedicated to the pubic symphysis region are acquired. Coronal oblique (axial oblique) images, including proton density (PD) and axial fat-saturated FSE T2-weighted images, are obtained by paralleling the arcuate line of the pelvis or the anterior iliac crest, as defined from a sagittal localizer sequence. The primary benefit of these oblique sequences is that they allow a better angle for evaluation of the adductor longus tendons and rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis. These sequences are also useful to assess for true inguinal hernias. Sagittal PD and FSE fat-saturated T2-weighted sequences using the small field of view are also obtained, allowing for excellent evaluation of the aponeurosis and its periosteal attachment to the anterior and anteroinferior pubic ramus. The nonfat-suppressed PD FSE sequences in particular are useful in assessing prior inguinal or core surgeries and potential reinjury. The imaging protocol is summarized in Table 1 .

| Sequence | Field of View | Matrix | NEX | Slice Thickness/Skip | TR | TE | TI | Echo Train Length | Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronal STIR | 28–36 (both hips) | 256 × 192 | 2–3 | 4 mm/1 mm | >2000 | 20–40 | 150 | 8 | 16 |

| Coronal T1 SE | 28 (both hips) | 256 × 256 | 1–2 | 4 mm/1 mm | 400–800 | Minimum | N/A | N/A | 16 |

| Axial T2 FSE fat-saturated | 28 (both hips) | 256 × 256 | 2–3 | 5 mm/1 mm | >2000 | 50–60 | N/A | 8 | 16 |

| Axial oblique PD FSE fat-saturated | 20 | 256 × 192 | 1–2 | 4 mm/0.5 mm | 3000 (maximum) | 25–30 | N/A | 4 | 16 |

| Axial oblique T2 FSE fat-saturated | 20 | 256 × 192 | 2–3 | 4 mm/0.5 mm | >2000 | 50–60 | N/A | 8 | 16 |

| Sagittal T2 FSE fat-saturated | 20–22 | 256 × 192 | 2–3 | 4 mm/0.5 mm | >2000 | 50–60 | N/A | 8 | 16 |

| Sagittal PD FSE fat-saturated | 20–22 | 256 × 256 | 2–3 | 4 mm/0.5 mm | >2000 | 20–30 | N/A | 8 | 16 |

MRI findings

Systematic assessment of images allows diagnosis of not only rectus abdominis/adductor longus aponeurosis injuries, but other possible etiologies of groin pain, including pelvic muscle strains and tears, osteitis pubis, fracture, sacroiliitis, visceral pathology, and intrinsic hip disorders. This, in turn, can dictate referral to the appropriate clinical subspecialist.

Rectus Abdominis/Adductor Aponeurosis Injury

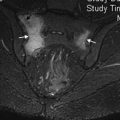

In the clinical setting of athletic pubalgia, rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis injuries are the most frequently encountered lesions at MRI. These injuries involve the caudal rectus abdominis, adductor longus origin, and pubic tubercle periosteum. Frequently, interstitial tearing or detachment of the lateral edge of the caudal rectus abdominis is noted, with confluent involvement of the adductor longus tendon. Morphologic symmetry is key in diagnosing this lesion, and its identification shows a high correlation with the situs of unilateral symptomatology. On axial images, the lesion can manifest as a visible deficiency of the rectus abdominis on cross section just anterior to the pubic tubercle. This deficiency is often positioned immediately posteromedial to the superficial ring, where the injured rectus abdominis shows an acutely angled contour in contrast to the normal, curvilinear morphology on the noninjured side. These patients often present with insidious groin pain and focal tenderness at the pubic tubercle. This lesion, in particular, is commonly treated with surgical pelvic floor repair.

In the setting of a unilateral rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis lesion, MRI often demonstrates subenthesial marrow edema at the pubic tubercle, the site of the caudal rectus abdominis insertion. This edema is confined to the anteroinferior aspect of the pubic body at the site of the attachment of the aponeurosis, unlike osteitis pubis, which spans the full anteroposterior course of the pubic body. The adductor longus tendon may be enlarged, demonstrate interstitial tearing, or be completely detached from the pubis. Interstitial tearing is manifested by fluid signal interspersed within the tendon. Detachment is often accompanied by a hematoma interposed between the tendon and the underlying pubis ( Fig. 4 ).