CHAPTER 20 Male Reproductive System

ANATOMY OF THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Testis and Epididymis

Testicular parenchyma consists primarily of seminiferous tubules where spermatogenesis takes place. These are soft, convoluted tubular structures that resemble strands of spaghetti several microns in diameter. The tubules are compacted together and are encapsulated within the tunica albuginea, giving the testis its ovoid shape (Fig. 20-1). A small incision or laceration in the tunica allows the seminiferous parenchyma to spill out like spaghetti from a plastic bag. The mediastinum testis is a septum that runs within the testicular parenchyma, providing a lattice for the vascular structures and efferent ductules that carry sperm from the seminiferous tubules to the epididymis.

Prostate and Seminal Vesicles

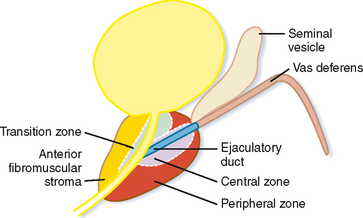

The prostate gland can be divided into one-third nonglandular and two-thirds glandular elements. The nonglandular components of the gland consist primarily of the anterior fibromuscular stroma and prostatic urethra. The fibromuscular stroma is located directly anterior to the urethra and includes the majority of the anterior lobe of the prostate (Fig. 20-2).

The bladder neck enters the base of the prostate centrally to join the proximal prostatic urethra. The ejaculatory ducts enter the prostatic urethra at a posterior mound called the verumontanum, defining the beginning of the distal prostatic urethra.

NORMAL IMAGING APPEARANCE OF THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Scrotal Contents

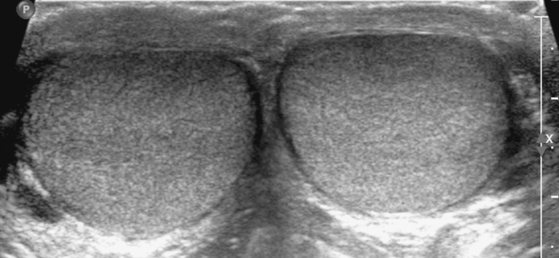

By US, each testis is an ovoid structure that is homogenous and mildly hypoechoic compared with the sparse adjacent soft tissues (Fig. 20-3). Because it is not possible to compare the echogenicity of the testes with other organs, it may be difficult to identify diffuse bilateral abnormalities of echogenicity. Fortunately, most testicular disease processes result in focal, multifocal, or diffuse unilateral abnormalities.

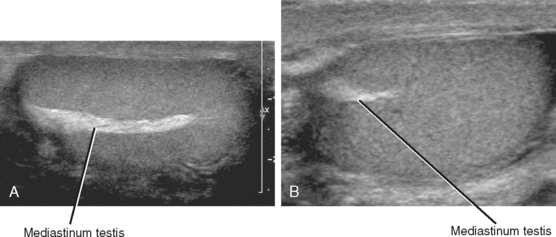

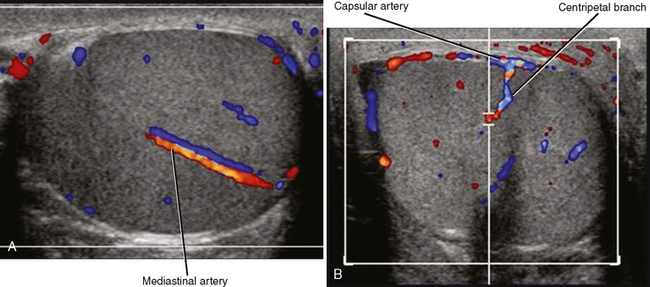

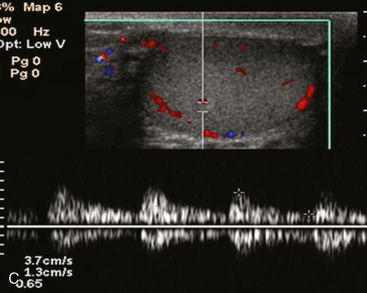

An echogenic line (the mediastinum testis) can usually be identified with US, bisecting the testis along its long axis asymmetrically (Fig. 20-4). A mediastinal artery is visible about 50% of the time and can mimic a small cyst or mass when viewed in cross section. Elongating the vessel and use of color Doppler imaging confirm the vascular nature of this finding (Fig. 20-5). Capsular arteries underlie the tunica albuginea and give rise to centripetal branches that radiate inward. Spectral Doppler demonstrates a low-resistance arterial waveform, with resistive indices typically between 0.50 and 0.75.

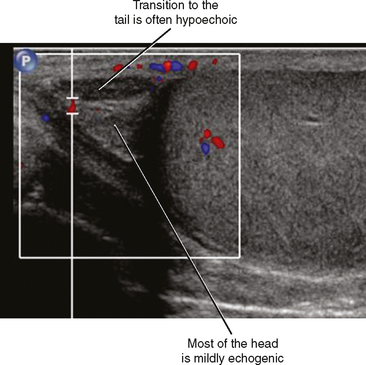

The head of the epididymis is seen on sagittal US images as a triangular, solid structure adjacent to the superior pole of the testis. Although the epididymal head is usually mildly echogenic compared with the testis, the tubules become more organized in the tail, which can render the tail hypoechoic. This can result in a “two-toned” appearance at the junction of the epididymal head and body (Fig. 20-6).

Prostate and Seminal Vesicles

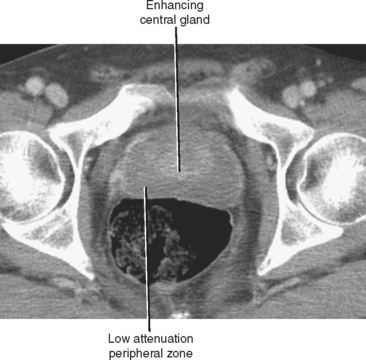

Typical appearance of the prostate on CT is an ovular soft-tissue density, often difficult to separate from the surrounding fascia and musculature. Large BPH nodules and global prostatic enlargement are sometimes evident as irregular soft-tissue nodules seen encroaching into the bladder base, often with associated bladder wall thickening. Crude zonal anatomy can be appreciated on contrast-enhanced images in patients with BPH, as the central gland enhances heterogeneously, delineating it from the surrounding hypovascular peripheral zone (Fig. 20-7). Calcification within the prostate gland is common and usually asymptomatic, although it is more common in men with recurrent prostatitis, BPH, and a variety of metabolic disorders. Calcification of the seminal vesicles and vas deferens are also common and are associated with diabetes mellitus.

Figure 20-7 Enhanced axial computed tomography in a 42-year-old man demonstrates some limited zonal anatomy.

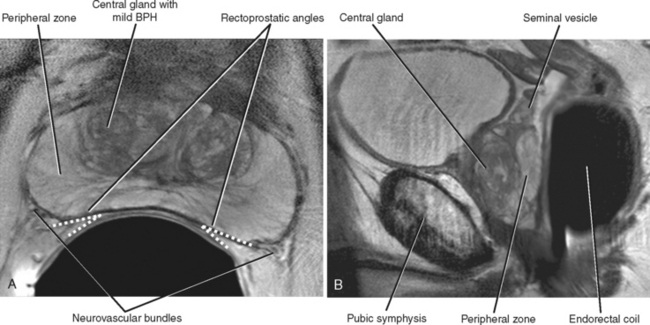

T2-weighted MR images provide improved definition of multiplanar prostatic zonal anatomy compared with other imaging modalities (Fig. 20-8). The peripheral zone consists of glandular tissue high in water content, giving it a bright appearance on T2-weighted images. The transitional and central zones of the central gland are difficult to delineate as separate structures in the young male individual, but together appear as intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging. As the patient ages, the transitional zone and periurethral glandular tissues enlarge, compressing the central zone and creating the surgical pseudocapsule between the hyperplastic transitional zone and the surrounding peripheral zone.

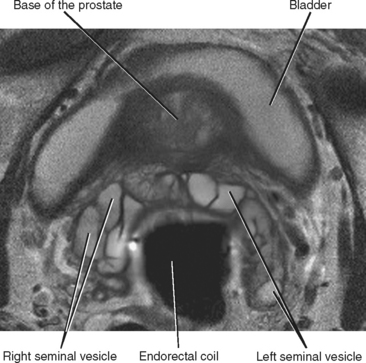

The seminal vesicles can be best visualized on coronal and axial images as clusters of high-T2 signalintensity tubules just cranial to the posterior prostatic base (Fig. 20-9). The course of the urethra through the prostate is best depicted on sagittal images.

SCROTAL PAIN

Differential Diagnosis and Triage of Patients with Scrotal Pain

The main goal of imaging for acute scrotal pain is to identify those disease processes that require urgent surgical therapy. Sonographic evaluation usually allows effective triage of patients into one of three categories as shown in Table 20-1.

Table 20-1 Triage of Patients with Scrotal Pain According to Ultrasound Findings

| Management | Ultrasound Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| No treatment necessary | |

| Medical therapy usually sufficient | |

| Surgical intervention should be considered | |

| Urgent surgical intervention required |

Although these processes can be usually differentiated from one another using US, correct diagnosis often requires “hands-on” sonographic evaluation because correlating physical examination findings such as tenderness with sonographic findings can improve specificity. Because many of these disease processes have helpful clinical discriminators, it can be useful to ask the patient questions regarding onset, location, and duration of pain while scanning. Table 20-2 lists additional clinical discriminators.

Table 20-2 Differentiating Common Causes of Scrotal Pain

| Diagnosis | Clinical Discriminators | Ultrasound Discriminators |

|---|---|---|

| Epididymitis | ||

| Orchitis | ||

| Testicular torsion | ||

| Segmental infarction of the testis | History of sickle cell disease, vasculitis, polycythemia vera, torsion/detorsion | |

| Varicocele | Palpable enlargement on physical examination that increases with Valsalva maneuver or standing | |

| Torsion of testicular or epididymal appendage | ||

| Hernia | Peristalsis of bowel or movement of fat with Valsalva maneuver | |

| Fournier gangrene | Echogenic foci of soft-tissue gas |

Torsion or Infection?

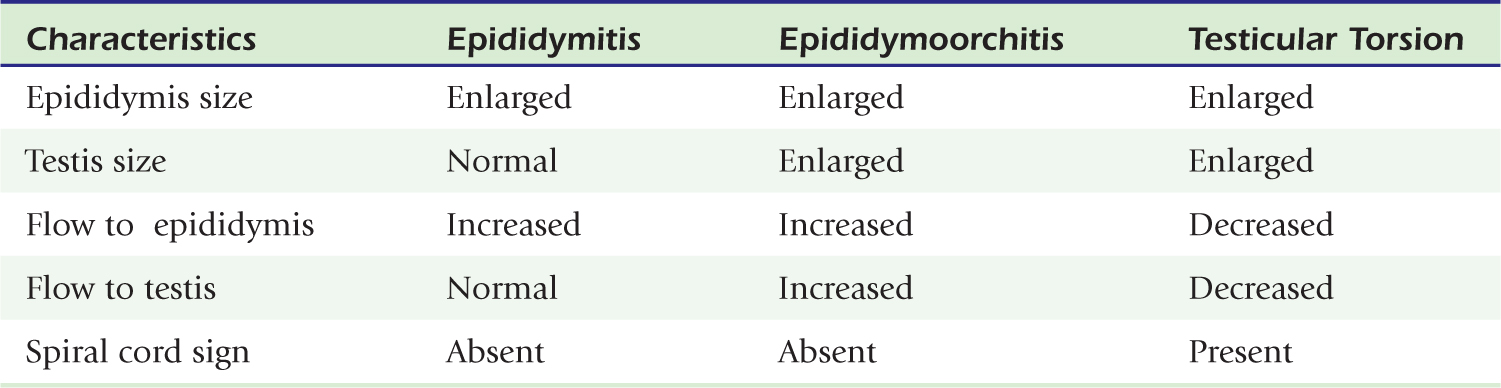

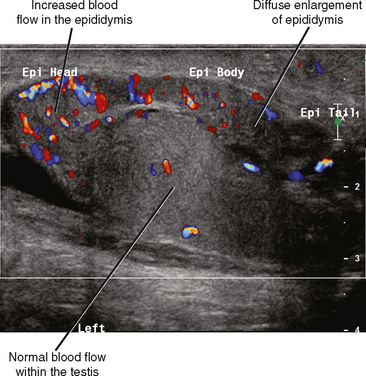

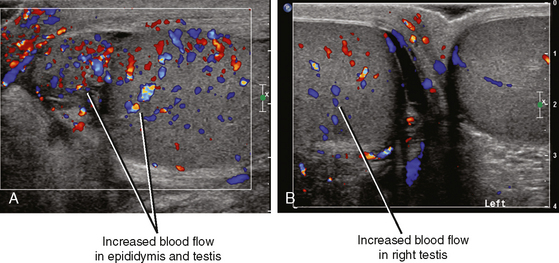

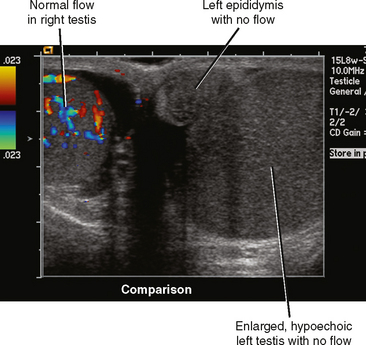

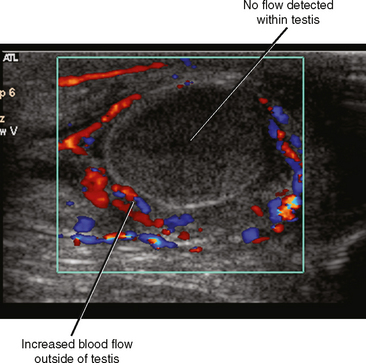

Fortunately, the imaging findings of infection and torsion are also usually quite disparate (Table 20-3). Typical sonographic features of epididymitis include an enlarged epididymis with increased blood flow on color Doppler (Fig. 20-10). In epididymoorchitis, there is also increased blood flow to the testis, which is often enlarged and mildly hypoechoic (Fig. 20-11). Although the testis and epididymis are typically enlarged and hypoechoic with torsion as well, blood flow is decreased or absent (Fig. 20-12). When evaluating blood flow for possible torsion, it is essential to keep in mind that there is often hyperemia surrounding an ischemic or infarcted testicle, so flow within the testicular parenchyma must be present to exclude torsion (Fig. 20-13). A spiral appearance of the spermatic cord vessels has also been described as a sign of torsion. Spectral Doppler evaluation usually demonstrates a low-resistance arterial waveform in orchitis and a high-resistance arterial waveform with decreased, absent, or reversed diastolic flow in testicular torsion. With torsion, loss of venous flow may precede loss of arterial flow on spectral Doppler imaging.

A Few Words About Appendages

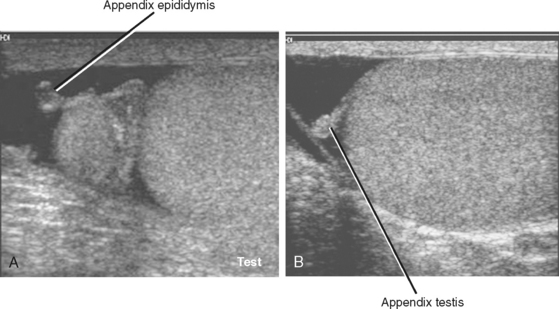

The appendix epididymis and appendix testis are small (usually ≤5 mm), nodular appendages of benign soft tissue that are often seen protruding from the respective structure. They are usually obscured by adjacent soft tissues during sonography but become more conspicuous when a hydrocele is present (Fig. 20-14). Rarely, one of these appendages may undergo torsion independent of the other scrotal structures, resulting in pain but no risk to the testis. This is more common in boys aged 7 to 14 years but can occur in adults as well. If sonography demonstrates no evidence of infection or torsion, and pain can be directly correlated to an appendix of the testis or epididymis, a diagnosis of appendiceal torsion can be made, resulting in appropriate conservative management.

Complications of Inflammatory Disease in the Scrotum

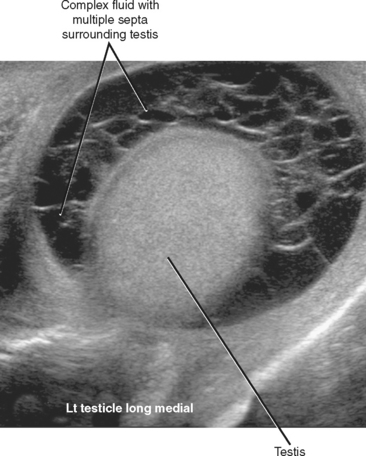

Several complications can occur when epididymitis, orchitis, or both go untreated or are incompletely treated. The most common of these complications is development of an infected hydrocele called a pyocele. A pyocele consists of infected fluid between the layers of the tunica vaginalis. Unlike simple hydroceles that develop in response to local inflammation, pyocele are usually septated and contain internal echoes (Fig. 20-15).

Epididymoorchitis can progress to form an intratesticular abscess. The pressure created by an expanding abscess within the confines of the tunica albuginea usually causes severe pain. Increased interstitial pressure can also decrease perfusion to the remainder of the testis, eventually resulting in global or segmental infarction. On US, abscesses are usually hypoechoic compared with adjacent testicular parenchyma, although internal echoes may be sufficient to make the abscess nearly isoechoic. Color Doppler imaging can be useful, demonstrating absent flow within the abscess cavity (Fig. 20-16).

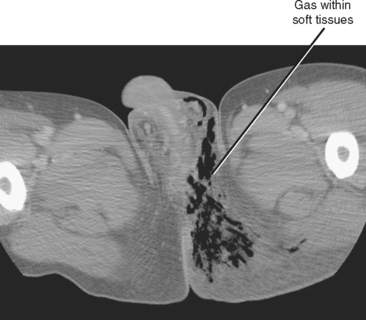

Fournier Gangrene

Two schools of thought exist regarding the use of imaging in the diagnosis and surgical planning of patients suspected of having Fournier gangrene: (1) Don’t image—just get them to the operating room; and (2) scan quickly with CT to define the expected extent of debridement necessary. If imaging is requested, speed of performance and interpretation are of the utmost importance. Key findings include gas and fat stranding in the subcutaneous soft tissues (Fig. 20-17). Because successful debridement is defined not only by width of resection but also by depth, try to identify areas of gas in adjacent muscles or other deep soft tissues.

FOCAL TESTICULAR LESIONS

Benign or Malignant?

Diagnosis of other benign intratesticular lesions demands more caution. Examples include epidermoid cyst, abscess, hematoma, focal infarction, and granulomatous orchitis. In many cases, the appearances of these lesions overlap that of malignancy; therefore, clinical factors (e.g., a history of trauma or fever) may be crucial in determining initial management. Table 20-4 summarizes US findings that favor a benign diagnosis.

Table 20-4 Focal Testicular Lesions: Ultrasound Findings That Favor Benign Disease

| Finding | Comments |

|---|---|

| Anechoic with smooth margins | Cyst of tunica albuginea or true intratesticular cyst depending on location |

| Absence of flow on color Doppler | |

| Enlargement of epididymis or thickening of the scrotum | Common with infection or inflammation including granulomatous orchitis |

| Tubular shape | |

| Concentric rings (laminated) | Epidermoid cyst |

| Straight margins or wedge shape | Focal testicular infarct |

| Pronounced mediastinal adenopathy with small testicular lesions | Consider sarcoidosis |

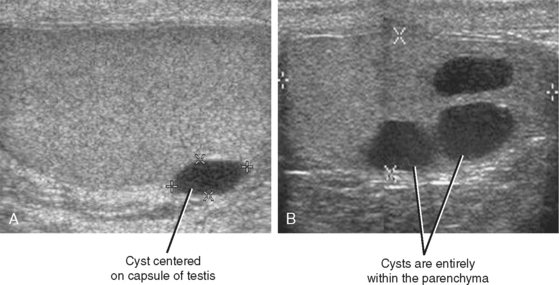

Testicular Cysts

Cysts of the tunica albuginea are usually found in men older than 40 years. They are located at the periphery of the testis, usually at the upper anterior or lateral margins. At grayscale US, they are usually biconvex or lentiform in shape and meet all the criteria of a simple cyst (Fig. 20-18). The cysts are typically unilocular but can be multilocular. Simple intratesticular cysts are similar in appearance to those of the tunica but can be located anywhere in the testis and can be solitary or multiple.

Germ cell tumors that undergo necrosis and teratomas with cystic components also can have a cystic appearance. However, cystic malignant lesions have a complex appearance with solid components or thick septations, or both, that distinguish them from simple cysts (Fig. 20-19).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree