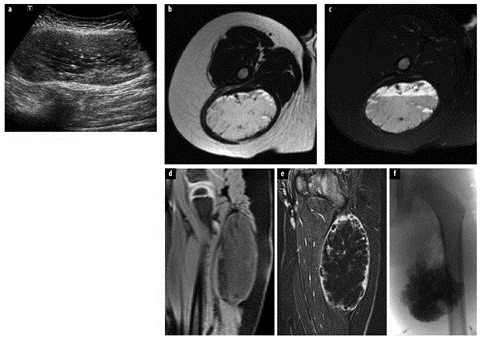

Fig. 1

Teenager presenting with a large intramuscular mass. X-ray demonstrates the presence of numerous phleboliths within the forearm, typical of a venous malformation

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [2] has two definite roles. First, it facilitates assessment of the full extent of the malformation and accurately localizes the lesion compared with vital anatomical structures. Second, it can add useful information to that obtained from the US in order to definitely identify the malformation. Decisions regarding the type of magnetic resonance (MR) sequences to be obtained and the need for gadolinium administration will depend on the results of the Doppler US examination. If the lesion is definitely identified by US as a VM or a lymphatic malformation (LM) there is no need for gadolinium administration.

Computed tomography is only indicated when cortical bone information is needed. This is very unusual in current practice.

Angiography is used only for exploration of arterio – venous malformation (AVM). Due to its aggressive — ness, especially in pediatrics, it is almost always performed only as the first step before embolization. In some rare cases, where the feeding vessels are not sufficiently clear on MRI, angiography will be performed to accurately determine the therapeutic strategy. In this situation, the risk of an increase in activity of the lesion as a result of stimulation by the catheter should always be considered.

What Are the General Clinical Features?

Vascular malformations are present at birth, but might not be visible at this stage. They grow in proportion with the growth of the patient. LMs and VMs are classically discovered at a young age (neonates, babies), while AVM tends to become symptomatic later (teenagers), secondary to trauma or hormonal influence. Therefore the patient and his/her family can be unaware of LM and VM and AVM at the time of presentation. When they become known, the length of evolution, over several months or years, is very helpful in restricting the differential diagnoses, especially diagnoses of malignancy. The malformations can be isolated or they can be part of more complex syndromes (e.g., Klippel Trenaunay, Parkes Weber, Sturge Weber, Bean) [3].

What Are the Main Types of Malformation, and How Are They Diagnosed and Treated?

Venous Malformation

VM is the most frequent vascular malformation. It represents an embryological abnormal development of the venous system. It can be either superficial or deeply located (muscle, bone). It can be localized at all anatomical sites; the most frequent sites are the face, cervical region and limbs.

Clinically, when visible, VM appears as a blue lesion with low rate of blood flow or no detectable blood flow. Some small hard spots can be palpable, representing clots in the lesion, the phleboliths. The lesion increases in size with tourniquet or gravity and decreases in reverse positioning.

On imaging, the lesion can have several different appearances [4]. It can be a tubular-shaped structure, resembling varices running superficially or deeply, and be associated, or not, with dysplasia of the deep venous system (Fig. 2). It can be a hypoechoic mass that is superficial or intramuscular (Figs. 3, 4), focal, with no blood flow or slow rate of flow detected by Doppler US. The major differential diagnosis to consider in pediatric practice is rhabdomyosarcoma. The presence of a fluid-fluid level in the lesion is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of VM. On the other hand, the presence of poor arterial flow (<15 cm/s) does not exclude a diagnosis of VM. The mass, often multiloculated, can present like a bunch of grapes, with or without communication with the adjacent venous system. It is then essential to look for a round-shaped phlebolith, with or without posterior shadowing. Suspicion of VM without US confirmation can have one of two outcomes: either the patient is older than 5 years and an MRI should be performed (axial T1 and T2, axial T1 gadolinium sequences and subtraction, delayed three-dimensional T1 fat-saturated acquisitions), or he is younger than 5 years and diagnostic tests should be done:

first, D-dimers, platelets and fibrinogen should be assayed to look for signs of local coagulopathy that favor a diagnosis of VM

then, treatment with aspirin 75 mg/day for at least 1 week should be commenced. Patients with VM will become less symptomatic or asymptomatic and the lesion will appear compressible and less echogenic on US.

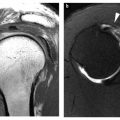

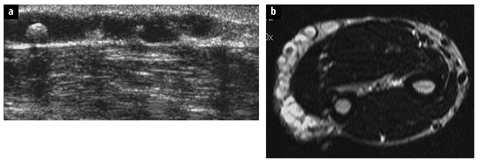

Fig. 2 a, b

A 7-year-old girl presenting with a venous malformation of the arm. a Ultrasound shows a tubular anechoic large venous structure containing a round hyperechoic structure with posterior shadowing (phlebolith). b T2 spin-echo sequence in the axial plane confirms the absence of deep extension of this malformation. A small phlebolith is visible as a hyposignal surrounded by the hypersignal of the stagnant fluid

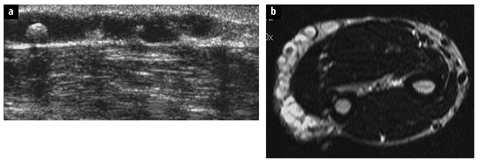

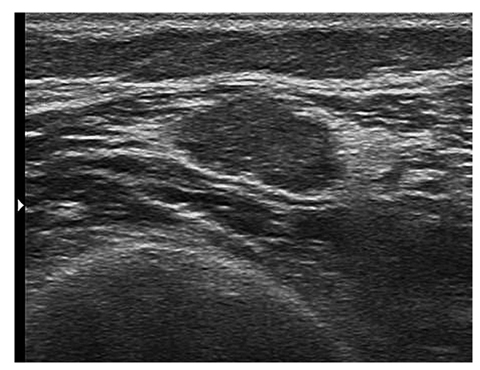

Fig. 3

16-year-old girl presenting with an acute pain of the left thigh corresponding to an acute thrombosis of a venous malformation. Ultrasound shows a hypoechoic homogeneous intramuscular mass surrounded by hyperechoic fatty tissue

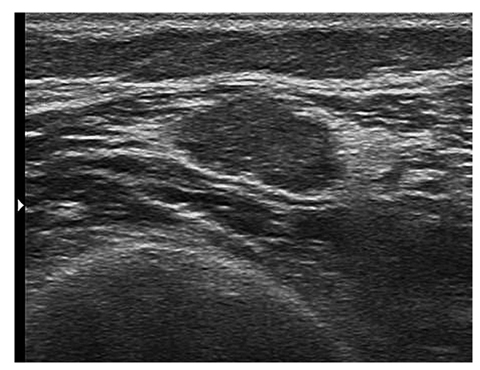

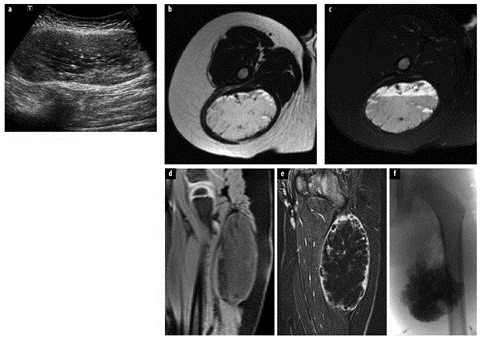

Fig. 4 a–f.

A 2-year-old boy who presented with an asymptomatic large mass subsequently discovered an intramuscular welllimited venous malformation in the left thigh. a Ultrasound convex probe: well-limited heterogeneous and hypoechoic intramuscular mass containing some hyper — echoic focus. b Magnetic resonance (MR) spin-echo (SE) T2 axial: the lesion appears almost in isosignal to fat with small hypo — signal focus (phleboliths). c MR SE T2 fat-saturated axial image (at the same level as in b) reveals a fluid-fluid level. d MR echo gradient (EG) T1 sagittal image confirms a fluid-fluid level and absence of a hypersignal. e MR EG T1 sagittal image after gadolinium and subtraction on a delayed acquisition: feeding of the lesion is very poor, from peripheral to center. f Percutaneous embolization: injection into the malformation through butterfly needles of foam of aetoxysclerol. No venous drainage is visible

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree