Computed tomography (CT) is commonly used in patients suspected of having a mediastinal mass or vascular abnormality (e.g., an aortic aneurysm). In general, CT is performed in two situations.

First, in patients with a mediastinal abnormality visible on plain radiographs, CT is almost always the preferred imaging procedure. CT is used to confirm the presence of a significant lesion, determine its location and relationship to vascular or nonvascular structures, and characterize the mass as solid, cystic, vascular, enhancing, calcified, inhomogeneous, or fatty.

Second, CT is often used in patients in whom there is clinical suspicion of mediastinal disease, regardless of plain radiograph findings. As an example, patients with lung cancer often have mediastinal lymph node enlargement (i.e., metastases) visible on CT when chest radiographs are normal.

Normal Mediastinal Anatomy

The mediastinum is the compartment situated between the lungs, marginated on each side by the mediastinal pleura, anteriorly by the sternum and chest wall, and posteriorly by the spine and chest wall. It contains the heart, great vessels, trachea, esophagus, thymus, considerable fat, and a number of lymph nodes. Many of these structures can be reliably identified on CT by their location, appearance, and attenuation.

For the purpose of CT interpretation, the mediastinum can be thought of as consisting of three almost equal divisions along the longitudinal axis of the patient, the first beginning at the thoracic inlet and the third ending at the diaphragm. In adults, each of these divisions is about 7 to 8 cm long and is thus made up of about 15 contiguous 5-mm slices. These can be remembered as follows:

- •

the supra-aortic mediastinum : from the thoracic inlet to the top of the aortic arch;

- •

the subaortic mediastinum : from the aortic arch to the superior aspect of the heart;

- •

the paracardiac mediastinum : from the heart to the diaphragm.

In each of these compartments, specific structures are consistently seen and need to be evaluated in every patient. The following description of normal anatomy is not comprehensive but is limited to the most important mediastinal structures.

Supra-Aortic Mediastinum

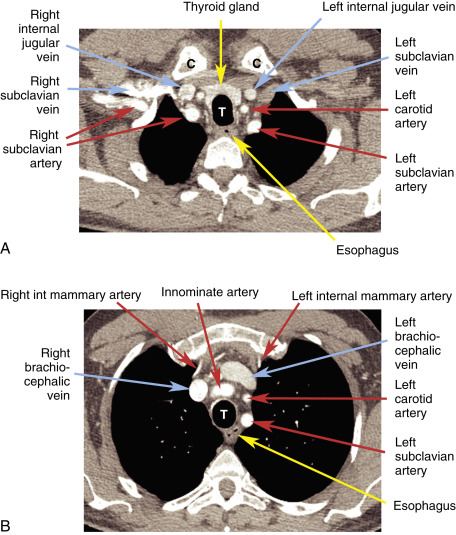

When one is evaluating a CT scan of this part of the mediastinum, it is a good idea to localize the trachea before doing anything else ( Fig. 2.1A ). The trachea is easy to recognize because it contains air, is seen in cross section, and has a reasonably consistent round or oval shape. It is relatively central in the mediastinum, from front to back and from right to left, and it serves as an excellent reference point. Many other mediastinal structures maintain a consistent relation to it.

At or near the thoracic inlet, the mediastinum is relatively narrow from front to back. The esophagus lies posterior to the trachea at this level ( Fig. 2.1 ), but depending on the position of the trachea relative to the spine, the esophagus can be displaced to one side or the other, usually to the left. It is usually collapsed and appears as a flattened structure of soft-tissue attenuation, but small amounts of air or air and fluid are often seen in its lumen.

In the supra-aortic mediastinum, the great arterial branches of the aortic arch and the great veins are the most recognizable structures. At or near the thoracic inlet, the brachiocephalic veins are the most anterior and lateral vascular branches visible, lying immediately behind the clavicular heads ( Fig. 2.1A and B ). Although they differ in size, their positions are relatively constant. The great arterial branches (innominate, left carotid, and left subclavian arteries) are posterior to the veins and lie adjacent to the anterior and lateral walls of the trachea. They can be reliably identified by their relative positions, but variations are common.

Below the thoracic inlet, anterior to the arterial branches of the aorta, the left brachiocephalic vein crosses the mediastinum from left to right ( Fig. 2.1C ) to join the right brachiocephalic vein, thus forming the superior vena cava ( Fig. 2.1C–E ). The left subclavian artery is most posterior and is situated adjacent to the left side of the trachea, at the three or four o’clock position relative to the tracheal lumen. The left carotid artery is anterior to the left subclavian artery, at the one or two o’clock position, and is somewhat variable in position. The innominate artery is usually anterior and somewhat to the right of the tracheal midline (11 or 12 o’clock position), but it is the most variable of all the great vessels and can have a number of different appearances in various patients or in the same patient at different levels.

Near its origin from the aortic arch, the innominate artery is usually oval and is somewhat larger than the other aortic branches. As it ascends toward the thoracic outlet, it may appear oval or elliptic because of its orientation or because of its bifurcation into the right subclavian and carotid arteries. This vessel can also be quite tortuous and can appear double if both limbs of a U-shaped part of the vessel are imaged in the same slice. Usually these vessels can be traced from their origin at the aortic arch to the point where they leave the chest, if there is any doubt as to what they represent.

Other than the great vessels, trachea, and esophagus, little is usually seen in the supra-aortic mediastinum. A few lymph nodes are normally visible. Small vascular branches, particularly the internal mammary veins , can be seen in this part of the mediastinum. In some patients the thyroid gland may extend into this portion of the mediastinum, and the right and left thyroid lobes may be visible on each side of the trachea. This appearance is not abnormal and does not imply thyroid enlargement. On CT the thyroid can be distinguished from other tissues or masses because its attenuation is greater than that of soft tissue (because of its iodine content). The thymus is sometime visible at this level anterior to the large vessels described earlier, within the prevascular space (described further later).

Subaortic Mediastinum

The subaortic mediastinum extends inferiorly from the top of the aortic arch to the upper portion of the heart ( Fig. 2.2 ). Whereas the supra-aortic region largely contains arterial and venous branches of the aorta and vena cava, this compartment contains many of the undivided mediastinal great vessels (the aorta, superior vena cava, and pulmonary arteries). This compartment also contains most of the important mediastinal lymph node groups. A few key levels in this part of the mediastinum will be discussed in detail.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree