Massimo Tonolini (ed.)Imaging of Ulcerative Colitis201410.1007/978-88-470-5409-7_2

© Springer-Verlag Italia 2014

2. Medical Needs

(1)

Department of Gastroenterology, “Luigi Sacco” University Hospital, Via G.B. Grassi, 74, 20157 Milan, Italy

Abstract

Diagnosis of UC is based on a combination of medical history, clinical symptoms, laboratory tests, and imaging data: no single imaging technique serves as a diagnostic gold standard for the diagnosis of UC. For clinical practice, some important informations about disease can settle some choice on patient’s management and therapy: disease activity, extent of inflammation, age of patient and of onset of symptoms, presence of intestinal or extraintestinal complications. Colonoscopy with biopsies plays an extremely important role in the diagnostic path and management of ulcerative colitis: it allows defining the presence and type of injury, as well as the extent of disease and the extent of histological involvement, but it is an invasive procedure, not always accepted by patients and not devoid of complications. So various radiologic methods, thanks to the technological development, have been proposed in recent years and have become now very important tools for the diagnosis and evaluation of patients with ulcerative colitis: they may not represent a valid alternative to endoscopy for now, but employed properly that they can be considered complementary methods. The most used diagnostic imaging modalities, including bowel ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance (MR), may be highly useful to highlight several intestinal abnormalities and to detect extraintestinal manifestations, and can help the clinician to determine the most appropriate therapy and future behavior.

Keywords

Ulcerative colitisDisease activityNeoplastic degenerationPrimary sclerosing cholangitisPouch disorders2.1 Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory condition causing continuous mucosal inflammation of the colon, characterized by alternate periods of remission and relapse, affecting a variable extent of the large bowel, with a way of spreading from distal to proximal segments.

In clinical practice, normally we need some important information about disease that can settle some choices on patient management and therapy such as extent of inflammation, age and date of symptoms onset, disease activity and presence of intestinal or extraintestinal complications.

UC is classified according to disease extent, using the Montreal endoscopic classification: in proctitis, left-sided colitis up to the splenic flexure, and in extensive colitis, beyond the splenic flexure. This classification has important implications because it influences the patient’s management and the choice of therapy. The extent of colitis influences the start and frequency of surveillance, being one of the risk factors for development of colorectal cancer: in left-sided and extensive colitis, endoscopic surveillance is generally recommended but no increased tumour risk is attributed to proctitis and these patients do not need surveillance.

Clinical disease activity is also divided into three groups: mild, moderate and severe. The definition of severity of disease is useful for clinical practice because it also influences the patient’s management, treatment modality and necessity of none, oral, intravenous or surgical therapy [1].

The diagnosis can be made at any age, but most patients are diagnosed at a young age and these patients have often an aggressive disease. So it is important to consider that many young patients have to undergo repetitive imaging procedures during the variable course of disease and monitoring the response to treatment. Furthermore, the long duration of disease and aggressiveness of colitis are other risk factors for development of colorectal cancer and can influence the start of surveillance.

The presence of concomitant extraintestinal complications can also influence patient management.

Diagnosis of UC is based on a combination of medical history, clinical symptoms, laboratory tests and imaging data: no single imaging technique serves as a diagnostic gold standard for the diagnosis of UC.

Colonoscopy plays an extremely important, pivotal role in the diagnostic path, and management of ulcerative colitis, as with biopsies, it allows to define the presence and type of injury, as well as the extent of disease and the extent of histological involvement, information necessary to direct the choice of treatment. However, colonoscopy is an invasive procedure, not always accepted by patients and not devoid of complications.

As alternative to colonoscopy, various methods for assessing the level of inflammation of the colorectal mucosa have been proposed in recent years. Radiologic methods, thanks to technological development, are important tools for the diagnosis and evaluation of patients with ulcerative colitis.

The most used diagnostic imaging techniques are ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR).

The clinician’s method of choice is based on the technique, the information that allows to obtain and the clinical condition of the patient. They may not represent a valid alternative to endoscopy for now, but employed properly they can be considered complementary methods.

Cross-sectional diagnostic imaging is used in ulcerative colitis with a dual purpose: (1) to suggest the diagnosis in patients with suspected chronic inflammatory disease and (2) to gain useful information for the management of patients with known ulcerative colitis and, in particular, to assess the extent and activity of the disease or the presence of complications, mainly the neoplastic degeneration of mucosa at early stages [2].

The first step is to evaluate the clinical status of the patient, as an active disease precludes the use of invasive techniques. By contrast, in the case of mild or moderate disease, colonoscopy, CT or MR colonography (which have almost completely supplanted the barium enema) may be highly useful due to numerous findings that can highlight, in particular, the subtle definition of the alterations of the wall and the possibility of detecting extraintestinal alterations.

In addition, in case of suspicion of intestinal or extraintestinal complications, the radiologic methods find ample space in their diagnosis and staging. Therefore, the task of the clinician is to identify the most useful imaging method to make the diagnosis, whereas that of the radiologist is to recognize and provide the clinician with information necessary for its decision [3].

This chapter reviews some of the common clinical situations that clinicians may face in patients with suspected or known UC, and discusses the information that is expected from the radiologist and the appropriate diagnostic imaging modalities.

2.2 Mild or Moderate Ulcerative Colitis

B.M, a 56-year-old man, complained of diarrhoea (3–4 bloody stools/day) for more than 6 weeks, associated with rectal bleeding and rectal urgency, with normal temperatures and no abdominal pain. Laboratory investigations showed normal markers of chronic inflammation (C-reactive protein CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate ESR) and normal full blood count. He was an ex-smoker (20 cigarettes/day, stopped at least 1 year ago) and had no other previous important pathologies. He underwent colonoscopy, which demonstrated the presence of a hyperemic and granular mucosa, with erosions of rectum and distal sigma and normal appearance of proximal colon. Histologic examination could establish the suspect of ulcerative colitis in distal samples.

Which information does the clinician need in this patient? What investigations should the patient undergo to arrive at a correct diagnosis and correct management?

For the clinician it is necessary to identify some basic parameters that will allow him to determine the most appropriate therapy and future behaviour: establish a correct diagnosis considering most common causes of chronic diarrhoea, evaluation of extent of disease, activity, severity of inflammation, presence of complications and post-treatment modifications.

Following ECCO guidelines, colonoscopy (preferably with ileoscopy and segmental biopsies including the rectum) is the preferred procedure to establish the diagnosis and extent of disease.

The differential diagnosis should be done between UC and acute inflammatory conditions such as infectious colitis, diverticular sigmoiditis and ischaemic lesions, the last one eventually requiring ultrasonographic study of mesenteric circulation.

Obviously, the initial diagnosis of UC requires the elimination of infectious causes of symptomatic colitis: stool specimens should be cultured for common pathogens and fresh stool samples should be examined for parasites [1].

Depending on extension and activity of disease, the severity of symptoms (such as diarrhoea, rectal blood loss, abdominal pain and fever) can vary, and laboratory parameters of the acute phase response (CRP, ESR and faecal calprotectin) may be normal or abnormal.

Rectosigmoid involvement is present in almost all patients at endoscopy: approximately 40–50 % of patients have disease limited to the rectum and recto-sigma, 30–40 % have a left-sided colitis and 20 % a total colitis.

Proximal spread of the disease, from the rectum to the cecum, occurs in continuity without areas of uninvolved mucosa. However, macroscopical sparing of the rectum has been described in children prior to treatment. In adults, normal or patchy inflammation of the rectum, is likely to be due to topical therapy, but endoscopic biopsies from mucosa with a normal appearance are usually abnormal.

The mucosa may appear normal when disease is in remission, whereas in mild and moderate disease the mucosa is erythematous, oedematous, of granular appearance, with loss of normal vascular pattern. In more severe cases, the mucosa is ulcerated and haemorrhagic. In long-standing disease, the mucosa may appear atrophic-cicatricial and inflammatory pseudopolyps may be present as a result of epithelial regeneration.

In UC, histological changes are limited to the mucosa and superficial submucosa with deeper layers being unaffected, except in fulminant colitis. The major changes include distortion of crypt architecture or crypt atrophy, mucin depletion, Paneth cell metaplasia and infiltrate in lamina propria of basal plasma cells.

However, since the disease is confined to the inner layers of the bowel wall, endoscopy with biopsies alone may be sufficient to detect and assess the extent and activity of the disease in UC. In this context, the role of cross-sectional imaging methods may be marginal, although they may be useful in presence of rectal sparing or atypical symptoms that can induce to diagnostic mistakes. Fundamental in these cases is, when possible, the differentiation of ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease, important from prognostic and therapeutic points of view.

In some cases, associated with colonoscopy, bowel ultrasound can be useful as complementary diagnostic technique to help differential diagnosis and it has the advantage of being non-invasive, easy to perform without prior preparation, easily repeatable and inexpensive [4].

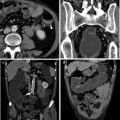

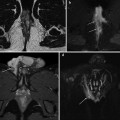

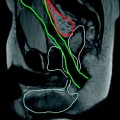

Imaging procedures such as CT or MRI colonography (enema CT with introduction of air or water and iodinated contrast media intravenously) can allow the simultaneous evaluation of the lumen, the gut wall and extraluminal changes, permitting a great panoramic study of abdomen and for this reason they are therefore becoming the investigation of choice in case of incomplete colonoscopy [5].

Definition of extension of colitis has a great importance to establish the first line therapy, which can be a topical therapy in proctitis, in the form of suppositories or enemas, or a systemic therapy often combined with topical therapy, in left-sided colitis or extensive colitis [1].